Transcription

ORIGINAL ARTICLEVeterans’ Access to and Use of Medicare and VeteransAffairs Health CareDenise M. Hynes, PhD, RN,*†‡ Kristin Koelling, MPH,* Kevin Stroupe, PhD,*†§¶Noreen Arnold, MS,* Katherine Mallin, PhD,* Min-Woong Sohn, PhD,†§ Frances M. Weaver, PhD,†lLarry Manheim, PhD,§ and Linda Kok, MS*Objectives: We examined the impact of access to care characteris tics on health care use patterns among those veterans dually eligiblefor Medicare and Veterans Affairs (VA) services.Methods: We used a retrospective, cross-sectional design to identifyveterans who were eligible to use VA and Medicare health care incalendar year 1999. We analyzed national VA utilization and Medi care claims data. We used descriptive and multivariable generalizedordered logit analyses to examine how patient, geographic, andenvironmental factors affect the percent reliance on VA and Medi care inpatient and outpatient services.Results: Of the 1.47 million veterans in our study population withoutpatient use, 18% were VA-only users, 36% were Medicare-onlyusers, and 46% were both VA and Medicare users. Among veteranswith inpatient use, 24% were VA only, 69% were Medicare only,and 6% were both VA and Medicare users. Multivariable analysisrevealed that veterans who were black or had a higher VA prioritywere most likely to rely on the VA. Patient with higher risk scoreswere most likely to rely on a combination of VA and Medicarehealth care. Patients who lived farther from VA hospitals were lesslikely to rely on VA health care, particularly for inpatient care.Patients living in urban areas with more health care resources wereless likely to rely on VA health care.Conclusions: VA health care provides an important safety net forvulnerable populations. Targeted approaches that carefully considerthe simultaneous impacts of VA and Medicare policy changes onFrom the *VA Information Resource Center (VIReC), Hines, Illinois; the†Midwest Center for Health Services and Policy Research, Hines, Illi nois; the ‡Stritch School of Medicine and Niehoff School of Nursing,Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Illinois; the §Feinberg School ofMedicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois; the ¶CooperativeStudies Program Coordinating Center, Hines, Illinois; and the lDepart ment of Neurology, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois.Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Admin istration Under-Secretary for Health (Project Number: XVA69-01) andthe VA Health Services Research and Development Service (ProjectNumbers: SDR 02-027 and SDR 98-004). Dr. Frances Weaver receivedfunding from the VA Health Services Research and Development Serviceas a VA Career Scientist during this study.The views put forth in this article are those of the authors and do notnecessarily represent the views of advisory board members or theDepartment of Veterans Affairs.Reprints: Denise M. Hynes, PhD, RN, P.O. Box 5000 (151V), Hines, IL60141. E-mail: denise.hynes@va.gov.Copyright 2007 by Lippincott Williams & WilkinsISSN: 0025-7079/07/4503-0214214minority and high-risk populations are essential to ensure veteranshave access to needed health care.Key Words: Veterans, Medicare, access to care, health services,health services research(Med Care 2007;45: 214 –223)In an increasingly complex and expensive health care envi ronment, patients seek care from multiple providers andacross health plans to meet their health care needs. Forelderly veterans eligible for benefits through the Departmentof Veterans Affairs (VA) and Medicare, such dual use hasbeen estimated to be as high as 54% among surgical patients1and nearly 30% among outpatients.2 Among some chronicdisease populations such as end-stage renal disease and men tal health, cross-systems use may be driven by differences inbenefit coverage for essential medications and resource avail ability as well as geographic factors.3,4 Cross-systems use, ordual use, of VA and non-VA care may enhance access,flexibility, and choice in health care for veterans, especiallyas demand for health care exceeds capacity. However, thereare concerns that dual use may create discontinuity andduplication of care, leading to wasteful use of health careresources with little or no benefit to patients. Alternatively, ajudicious use of both VA and Medicare systems may helppatients manage their diseases better with improved out comes. It is important to understand the patterns of dual useby veterans and the underlying determinants of seeking carein either or both systems of care.Few recent studies have examined overall patterns ofdual use between the VA and Medicare. Only a U.S. GeneralAccounting Office (GAO) analysis more than 10 years agoexamined the use of VA health care services by Medicareeligible veterans.5 Although more recent studies have dem onstrated how individual-level characteristics impact healthcare use among veterans, including residence in an urban orrural area,6,7 gender,8 –10 age,1,10 –12 distance from a VAfacility,13–15 and whether or not the veteran will be requiredto pay a copayment,16 none have examined the multipleeffects of these and other important access to care factors onpatients’ patterns of health care use across systems of care.Using detailed health care claims and utilization data, weMedical Care Volume 45, Number 3, March 2007

Medical Care Volume 45, Number 3, March 2007focus on the impact of access to care characteristics on healthcare use patterns among those dually eligible for services inthe 2 largest health care programs in the United States:Medicare and the VA.METHODSResearch Design and Study SampleWe used a retrospective, cross-sectional design to iden tify veterans who were eligible to use VA and Medicarehealth care in calendar year 1999. Our sampling frame com prised 6.4 million veterans who had used VA health careservices between calendar years 1997 and 1999, were eligibleto use VA health care because they were enrolled in theVeterans Health Administration, or received compensation orpension benefits from the VA. We combined data from oursampling frame with Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Ser vices (CMS) enrollment data using conservative matchingcriteria17 to ensure valid data linkages, which resulted in ancohort of 2.6 million veterans eligible for VA health care andenrolled in Medicare during 1999 (Fig. 1).We excluded individuals for whom veteran status wasunknown, individuals with missing or invalid zip codes, orthose who lived in Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories.Individuals who were 65 or younger on January 1, 1999, werealso excluded. Patients with end-stage renal disease (n 23,977) were excluded as a result of differences in costingand accounting for dialysis services in the VA and in Medi care. Individuals enrolled in a Medicare Choice (M C)plan during 1999 (n 430,657) were excluded because CMSdoes not collect claims data on M C enrollees, so we couldnot calculate their Medicare costs or their risk score. Finally,we excluded 63,037 veterans with no health care use in eitherVA or Medicare in 1999 because no information was avail able on other sources of health insurance and thereforeVeterans’ Use of Medicare/VA Health Carewhether there was any health care use outside of VA orMedicare. Our final cohort comprised 1.48 million veterans(see Fig. 1).Reliance on Veterans Affairs Health Care UseCategoriesWe calculated the percent reliance on VA health care asa percentage of total VA and Medicare costs in calendar year1999; inpatient and outpatient care reliance measures werecalculated separately. Because this measure was not normallydistributed, for analytic purposes, we also defined orderedcategories. For outpatient services, we defined 5 mutuallyexclusive ordered categories based on the proportion of anindividual patient’s total (VA and Medicare) health care costsfor outpatient services received in 1999 that were for VAhealth care. The groups included those with 0% of theiroutpatient health care costs attributable to VA health care(Medicare-only users), 1% to 25% of outpatient costs in theVA (mostly Medicare users), 26% to 74% of outpatient costsin the VA (equally dual users), 75% to 99% of outpatientcosts in the VA (mostly VA users), and those with 100% oftheir outpatient costs attributable to VA health care (VA-onlyusers). For inpatient services, we defined 3 categories result ing from the small number of veterans who had inpatientservices in both VA and Medicare: those with 0% of theirinpatient costs attributable to VA health care (Medicare-onlyusers), 1% to 99% of inpatient costs in the VA (dual users),and those with 100% of their inpatient costs attributable toVA health care (VA-only users).VA use was determined by searching all VA workloaddata files that contain information on inpatient or outpatientcare provided at a VA facility or paid for by the VA on a feebasis for calendar year 1999.18 Costs for VA health care usewere obtained from the VA Health Economics ResourceCenter (HERC) cost data sets, which use a Medicare paymentapproach to estimate average costs for VA inpatient andoutpatient events.19,20 Cost estimates for VA outpatient visitsare based on reimbursement rates from Medicare and otherhealth care payers to estimate hypothetical payments foroutpatient visits; these payments were adjusted to reflect theactual aggregate cost of VA outpatient care.19 Costs for VAinpatient stays in these data sets are calculated using aMedicare cost function estimate derived from characteristicsof the patient admission such as length of stay and diagnosisrelated group relative weights.20Medicare use was determined by searching CMS feefor-service (FFS) claims files. We included CMS claims filesfor inpatient services using the Inpatient Standard Analytic File(SAF) and for outpatient services using the Outpatient, HomeHealth Agency, and Carrier (physician/supplier) SAFs.18 Weused Medicare payments to estimate costs separately for inpa tient and outpatient care. Carrier claims that were concomitantwith an inpatient admission were classified as inpatient events.Access to Health Care FactorsFIGURE 1. Pathway from sampling frame to final cohort. 2007 Lippincott Williams & WilkinsWe examined 3 categories of access to care charac teristics: patient, geographic, and environmental. Thesecharacteristics are consistent with prior work on health215

Hynes et alcare behavior21,22 and empiric studies of health care demandamong veterans.5,6,13,15,23Patient CharacteristicsPatient characteristics included age, gender, race, vitalstatus, priority level within the VA, and a patient health statusrisk score. Age, gender, race, and vital status were obtainedfrom the Medicare Vital Status file, a source considered to beof superior quality to that in the VA files.24,25 Age wasparameterized as a 3-level variable grouping: 66 to 74 years,75 to 84 years, and 85 years or older. Race was examined asa dichotomous variable indicating black or nonblack race,because until recently, CMS did not collect data on otherminority groups and reliability of ethnicity data was poor.24VA priority level was defined as a dichotomous variable inwhich “high-priority” veterans included those who had aservice-connected condition or whose income was less than athreshold annually established by the VA (VA priority groups1– 6).23 The “low-priority” designation included only thosewhose income was greater than the annual income thresholdin 1999.To account for patient health status, we computed riskscores based on all VA and Medicare health care claims datausing the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) method.26 –28The HCC risk method has been used by CMS to risk-adjustpayments to Medicare Choice plans since 2004. The HCCmodel is unique because it uses groups of related conditions, orhierarchies, to limit the number of related conditions that con tribute to a person’s risk score. Less serious conditions in thesame hierarchy are excluded. For example, someone with myo cardial infarction (MI) may also have unstable angina in thesame year. Unstable angina will not contribute to the risk scorebecause it is ranked lower than MI in the same hierarchy. Thus,the hierarchical method reduces the sensitivity of the risk scoresto the coding variations by providers and is especially appropri ate to use in this study that involves 2 systems of care withdifferent incentives to code diseases.To calculate the HCC risk scores, we used demographicinformation, including age, gender, Medicaid eligibility, andoriginal reason for Medicare entitlement from the 1999 Medi care Denominator file. Medical conditions were determinedby combining all diagnostic codes from VA and Medicareinpatient and outpatient encounters during 1999. We dividedthe sample into quartiles based on HCC values separately forthe inpatient and outpatient users.Geographic FactorsWe considered 3 measures of geographic access: dis tances to the nearest VA inpatient hospital, VA outpatientcenter, and Medicare inpatient hospital based on prior re search.6,7,15 Distance was measured in miles as a straight-linedistance between the location of health care facility and thecentroid of the zip code of the patient’s residence and wasobtained from the VA Planning Systems Support Group.29 Asa result of collinearity between these distance variables, wechose to use only the distance to the nearest VA inpatienthospital in the regression models. We used a 5-level groupingto capture distance effects in the first 20 to 30 miles.14,15216Medical Care Volume 45, Number 3, March 2007Environmental CharacteristicsMeasures for the environmental category describe thepatient’s zip code or county of residence. The urban/ruralnature of the zip code is based on 2000 census data from theVA Planning Systems Support Group.29 Poverty level wasderived from the 2000 census as a dichotomous measureindicating whether at least 20% of households in the zip codewere below the poverty level (high poverty).30Descriptors of the health care resources in the individ ual’s county of residence included the number of physicians,the number of short-term general hospitals, and the number ofshort-term general hospital beds.30 As a result of collinearitybetween these variables, we chose to use only the number ofbeds in our final models. Counties were divided into quartilesbased on the number of beds: low (0 –125 beds), medium–low (126 –514 beds), medium– high (515–1697 beds), andhigh (1698 –24,791 beds).Statistical AnalysisWe used descriptive and multivariable analyses to ex amine how access to care factors affected patterns of relianceon VA and Medicare in 1999. We completed separate anal yses for outpatient care (n 1,474,417) and inpatient care(n 416,455). We used generalized ordered logit regressionin STATA31–33 to examine an increasing preponderance ofVA services relative to Medicare services. We used thisapproach because the independence of irrelevant alternativesassumption34 was not met for the multinomial logistic modeland the parallel regression assumption was not met for anordered logistic model. Unlike the ordered logistic model, theadvantage of the generalized ordered logit model is that itdoes not constrain the parameter estimates to be constantacross all the groups of interest, in this case our health careuse groupings. The generalized ordered logit model is spec ified as:Prob. (Yi j) exp(f0j Xi fj)/[1 exp(f0j Xi fj)], j 1, 2, . . ., M-1where M is the number of health care use categories (foroutpatient use M 5; for inpatient use M 3); j is the healthcare use category (for outpatient use: 1 Medicare only, 2 mostly Medicare, 3 equally dual, 4 mostly VA, 5 VAonly; for inpatient use: 1 Medicare only, 2 dual, 3 VAonly); Yi is the category of health care use for the ith patient; andXi are the patient, geographic, and environmental variables. Akey aspect of this model is that it allows the estimated coeffi cients, f, for variables that violate the parallel lines assumption,to vary across all categories, j, but remain constant for across allcategories for variables that do not violate the parallel linesassumption.31To control for unobserved cross-network heterogeneity,our generalized ordered logit regressions included dummyvariables representing the 22 Veterans Integrated ServiceNetwork in which a veteran resided. We also included adummy variable indicating whether the individual died dur ing the year. We report odds ratios (ORs) for all parameterestimates except for the control variables. Regression resultsreported are for the full sample. Although not reported here, 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

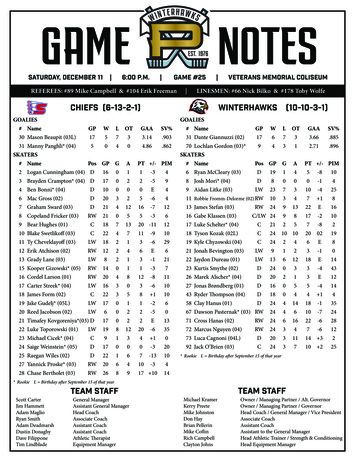

Medical Care Volume 45, Number 3, March 2007we also estimated the same model using a 5% random sampleto ascertain any effects resulting from sample size and foundsimilar results.35RESULTSOutpatient UseAmong patients who had VA or Medicare outpatienthealth care use, 18% used only VA care, nearly 36% usedonly Medicare, and 46% used a combination of VA andMedicare services (Table 1). Patients who used both VA andMedicare services had higher outpatient costs than patientswho used VA or Medicare services only. Patients who usedmostly Medicare services had the highest average annual costper patient ( 5088). The other dual use groups also hadhigher mean outpatient costs ( 3112 for mostly VA and 2815 for equally dual users) than patients who were singlesystem users ( 2323 for Medicare only and 2645 for VAonly users).Among all outpatient users, the median age was 74years, 8% were black, 2% were women, 79% had a highpriority designation by the VA, and 25% lived within 10miles of a VA hospital. For environmental characteristics,79% lived in an urban zip code and 14% of patients lived inareas with high poverty rates.Table 2 shows the generalized ordered logit regressionresults for the outpatient model. As patient age increased, thelikelihood of relying on VA care decreased. For example,veterans who were 75 to 84 years of age were less likely (OR 0.64) and veterans 85 years and older were even less likely(OR 0.50) than those aged 66 to 74 years to use the VAexclusively than to use any Medicare services. Black veteranswere increasingly likely to rely on VA care. Black veterans weremore likely to rely on VA care exclusively than nonblacks(OR 2.32) and were always more likely to rely on some VAcare than to use Medicare services exclusively. Male veteranswere less likely to rely exclusively on VA care (OR 0.87) thanfemale veterans and less likely overall to rely on some VA care.Patients’ priority status for VA services had the largest impacton reliance on VA health care. Patients with a high prioritydesignation were far more likely than their low-priority coun terparts to rely exclusively on VA care (OR 3.59) and morelikely overall to rely on some VA care.With regard to health risk, the lowest-risk patients weremost likely to use VA services exclusively. As risk scoreincreased, the reliance on VA services decreased. For exam ple, compared with the lowest risk group, veterans who hadmedium–low risk scores were less likely (OR 0.84) to usethe VA exclusively. Similarly, veterans who were at medium–high risk were less likely (OR 0.63) and those who were athigh risk were least likely (OR 0.33) to use VA exclusivelycompared with the lowest risk group. Moreover, patients athighest risk were also less likely to use Medicare exclusively.For example, the highest risk patients were more likely (OR 1.42) to use any VA service than to use Medicare only. Thispattern indicates that the highest risk patients were using acombination of VA and Medicare services.Results for the geographic distance variable are consis tent with prior research: as distance to a VA inpatient hospital 2007 Lippincott Williams & WilkinsVeterans’ Use of Medicare/VA Health Caredecreased, the likelihood of using VA services exclusivelyincreased. Veterans who lived more than 40 miles from a VAhospital were less likely (OR 0.30) to use the VA exclu sively compared with those who lived within 5 miles, andreliance on VA care decreased with greater distances from aVA hospital.We found that patients who lived in urban areas or inareas with a greater number of hospital beds, where choicesfor health care tend to be greater, were less likely to rely onVA care exclusively than patients in rural areas (OR 0.78)or in counties with fewer hospital beds (OR 0.89). Also,patients living in high poverty areas were more likely (OR 1.28) to rely on VA services exclusively.Inpatient UseOf the 416,455 veterans who had VA or Medicareinpatient health care use, 24% used only VA care, 69% usedonly Medicare, and 6% used a combination of VA andMedicare inpatient services (Table 3). Average annual inpa tient costs for dual users were more than double the averagecosts for patients using a single system ( 34,668 for dualusers vs. 16,464 for VA only and 15,612 for Medicare-onlyusers). Similarly, dual users had an average of 3.46 inpatientadmissions compared with 1.58 for VA-only users and 1.71for Medicare-only users.Among inpatient users, the median age was 75 years,9% were black, 2% were women, 83% had a high prioritydesignation by the VA, and 25% lived within 10 miles of aVA hospital. For environmental characteristics, 79% lived inan urban zip code and 15% of patients lived in areas with highpoverty rates. Distributions were similar when we examinedonly those patients who had at least 2 inpatient admissionsduring the year.Table 4 shows generalized ordered logit regressionresults for the inpatient model. Regression results were con sistent with the outpatient model for trends and showed anincreasing likelihood of reliance on VA use among patientswho were younger, black, female, healthier, had a highpriority designation within the VA, lived in a rural area, livedin a high poverty area, lived close to a VA hospital, and livedin a county with the fewest number of hospital beds. Only themagnitude of the effects differed. In particular, patients whowere designated as high priority for VA care had a greaterlikelihood than low-priority veterans (OR 5.19) to use theVA exclusively for their inpatient care.DISCUSSIONWe characterized veterans who were eligible to useboth VA and Medicare FFS in 1999 in 5 health care usergroups based on their reliance on VA health care relative toMedicare. We examined inpatient and outpatient care sepa rately but found similar patterns of reliance on VA care; wefound an increasing preponderance of VA use among patientswho were younger, black, female, healthier, had a highpriority designation in the VA, lived in a rural area, lived ina high poverty area, lived close to a VA hospital, and lived ina county with the fewest numbers of hospital beds. Althoughthese results for specific variables are consistent with priorresearch, several issues are noteworthy.217

Medical Care Volume 45, Number 3, March 2007Hynes et alTABLE 1.Characteristics of Users of Veterans Affairs (VA) or Medicare Outpatient ServicesOutpatient UsersTotal (n)Median paymentsVAMedicareTotalMean paymentsVAMedicareTotalAge as of January 1, 1999Median66–74 (%)75–84 (%)85 (%)RaceNonblack (%)Black (%)GenderFemale (%)Male (%)VA priority levelLow (%)High (%)Hierarchical condition categoryrisk scoreMedianLow (%)Medium–low (%)Medium–high (%)High (%)Type of zip codeRural (%)Urban (%)Poverty level of zip codeLow (%)High (%)Distance to nearest VA hospitalMedian0–4.9 miles (%)5–9.9 miles (%)10–19.9 miles (%)20–39.9 miles (%)40 miles (%)Number of hospital beds incountyLow (%)Medium–Low (%)Medium–high (%)High (%)TotalVA Only*Mostly VA†Equally Dual‡Mostly Medicare§Medicare Only¶1,474,417270,993 (18.4%)176,242 (12.0%)235,096 (15.9%)267,408 (18.1%)524,678 (35.6%) 305 750 1838 1401 0 1401 1803 145 2015 839 917 1837 283 3089 3484 0 1332 1332 1056 2055 3112 2323 0 2323 2820 292 3112 1342 1473 2815 432 4656 5088 0 2645 264574 yr53.742.53.972 yr63.633.82.673 yr57.339.73.074 yr53.842.93.374 yr50.546.13.575 388.511.588.911.130 miles12.612.014.719.840.918 miles21.615.514.917.730.333 miles13.910.912.419.743.136 miles11.310.312.719.846.135 miles9.510.214.520.545.430 23.122.325.526.425.8*Veterans who had 100% of their outpatient health care costs in the VA and none in Medicare.†Veterans who had 75–99% of their outpatient health care costs in the VA and 1–25% in Medicare.‡Veterans who had 26 –74% of their outpatient health care costs in the VA and 26 –74% in Medicare.§Veterans who had 1–25% of their outpatient health care costs in the VA and 75–99% in Medicare.¶Veterans who had none of their outpatient health care costs in the VA and 100% in Medicare.218 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Medical Care Volume 45, Number 3, March 2007TABLE 2.Veterans’ Use of Medicare/VA Health CareAdjusted Odds Ratios of Using Veterans Affairs (VA) or Medicare Outpatient Services*VA Only, Mostly VA,Equally Dual, andMostly MedicareUsers Vs. MedicareOnly UsersVA Only, Mostly VA,and Equally DualUsers Vs. MostlyMedicare andMedicare-Only UsersVA Only and Mostly VAUsers Vs. Equally Dual,Mostly Medicare, andMedicare-Only UsersVA-Only Users Vs.Mostly VA, Equally Dual,Mostly Medicare, andMedicare-Only 0.760.70Ref0.820.730.73Age as of January 1, 199966–7475–8485 RaceNonblackBlackGenderFemaleMaleVA priority levelLowHighHierarchical condition categoryrisk scoreLowMedium–lowMedium–highHighType of zip codeRuralUrbanPoverty level of zip codeLowHighDistance to nearest VA hospital0–4.9 miles5–9.9 miles10–19.9 miles20–39.9 miles40 milesNumber of hospital beds in *Odds ratios are also adjusted for a veteran’s vital status and the Veterans Integrated Service Network of residence. No variables in this model met the parallel lines assumption;parallel lines were not imposed for any variable. All odds ratios are statistically significant at the P 0.01 level.In our models, VA priority status was the strongestfactor affecting an individual’s reliance on VA care. A highpriority designation in the VA means that 100% of veterans’health care services are covered by the VA; there are nocopayments for any services, except medications for condi tions unrelated to military service. The low priority designa tion has changed over time depending on the resourcesavailable in the VA budget. In 1999, although the VA offeredservices to all veterans, copayments were required for ser vices provided to low-priority veterans, ie, those with higherincomes.23 As VA copayments and income thresholdschange, future research should consider the extent to whichsuch changes impact the reliance on VA health care. 2007 Lippincott Williams & WilkinsSecond, we found that for outpatient and inpatient care,blacks were more likely to rely on the VA exclusively fortheir care beyond that explained by other factors. Blacks werealso more likely to rely on some VA care even when theyused Medicare services. Consistent with previous surveyresearch that blacks, compared with nonblacks, are morelikely to prefer VA to non-VA providers for their outpatientcare,36,37 this result suggests that policy initiatives aimed atrestructuring VA services may disproportionately affect blackveterans. Paradoxically, since 2004, the VA’s ability to mon itor racial disparities has been hampered by poor data qualityon race and ethnicity of its patients. As a result of implemen tation of an Office of Management and Budget (OMB)219

Medical Care Volume 45, Number 3, March 2007Hynes et alTABLE 3.Characteristics of Users of Veterans Affairs (VA) or Medicare Inpatient ServicesTotal (n)Mean admissionsVAMedicareTotalMedian paymentsVAMedicareTotalMean paymentsVAMedicareTotalAge as of January 1, 1999Median66–74 (%)75–84 (%)85 (%)RaceNonblack (%)Black (%)GenderFemale (%)Male (%)VA priority levelLow (%)High (%)Hierarchical condition category risk scoreMedianLow (%)Medium–low (%)Medium–high (%)High (%)Type of zip codeRural (%)Urban (%)Poverty level of zip codeLow (%)High (%)Distance to nearest VA hospitalMedian0–4.9 miles (%)5–9.9 miles (%)10–19.9 miles (%)20–39.9 miles (%)40 miles (%)Number of hospital beds in countyLow (%)Medium–low (%)Medium–high (%)High (%)TotalVA Only*Dual†Medicare Only‡416,455102,234 (24.5%)26,591 (6.4%)287,630 11.71 0 6213 10,116 8411 0 8411 9985 8510 24,206 0 9738 9738 5302 11,780 17,082 16,646 0 16,646 19,038 15,630 34,668 0 15,612 15,61275 yr47.946.85.474 yr53.541.64.975 yr49.345.55.275 23.276.820.579.584.715.379.720.380.319.786.913.129 miles13.412.114.519.540.416 miles23.315.715.017.928.227 miles16.412.913.618.139.034 .130.828.923.821.126.224.626.325.623.5*Veterans who had 100% of their inpatient health care costs in the VA and none in Medicare.†Veterans who had 1–99% of their inpatient health care costs in the VA and 1–99% in Medicare.‡Veterans who had none of their inpatient health care costs in the VA and 100% in Medicare.220 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Medical Care Volume

Veterans, Medicare, access to care, health services, health services research (Med Care. 2007;45: 214-223) I. n an increasingly complex and expensive health care envi across health plans to meet their health care needs. For elderly veterans eligible for benefits through the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Medicare, such dual use has