Transcription

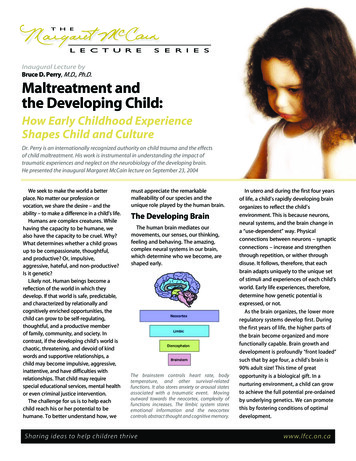

T H EL E C T U R ES E R I E SInaugural Lecture byBruce D. Perry, M.D., Ph.D.Maltreatment andthe Developing Child:How Early Childhood ExperienceShapes Child and CultureDr. Perry is an internationally recognized authority on child trauma and the effectsof child maltreatment. His work is instrumental in understanding the impact oftraumatic experiences and neglect on the neurobiology of the developing brain.He presented the inaugural Margaret McCain lecture on September 23, 2004We seek to make the world a betterplace. No matter our profession orvocation, we share the desire – and theability – to make a difference in a child’s life.Humans are complex creatures. Whilehaving the capacity to be humane, wealso have the capacity to be cruel. Why?What determines whether a child growsup to be compassionate, thoughtful,and productive? Or, impulsive,aggressive, hateful, and non-productive?Is it genetic?Likely not. Human beings become areflection of the world in which theydevelop. If that world is safe, predictable,and characterized by relationally andcognitively enriched opportunities, thechild can grow to be self-regulating,thoughtful, and a productive memberof family, community, and society. Incontrast, if the developing child’s world ischaotic, threatening, and devoid of kindwords and supportive relationships, achild may become impulsive, aggressive,inattentive, and have difficulties withrelationships. That child may requirespecial educational services, mental healthor even criminal justice intervention.The challenge for us is to help eachchild reach his or her potential to behumane. To better understand how, wemust appreciate the remarkablemalleability of our species and theunique role played by the human brain.The Developing BrainThe human brain mediates ourmovements, our senses, our thinking,feeling and behaving. The amazing,complex neural systems in our brain,which determine who we become, areshaped early.The brainstem controls heart rate, bodytemperature, and other survival-relatedfunctions. It also stores anxiety or arousal statesassociated with a traumatic event. Movingoutward towards the neocortex, complexity offunctions increases. The limbic system storesemotional information and the neocortexcontrols abstract thought and cognitive memory.Sharing ideas to help children thriveIn utero and during the first four yearsof life, a child’s rapidly developing brainorganizes to reflect the child’senvironment. This is because neurons,neural systems, and the brain change ina “use-dependent” way. Physicalconnections between neurons – synapticconnections – increase and strengthenthrough repetition, or wither throughdisuse. It follows, therefore, that eachbrain adapts uniquely to the unique setof stimuli and experiences of each child’sworld. Early life experiences, therefore,determine how genetic potential isexpressed, or not.As the brain organizes, the lower moreregulatory systems develop first. Duringthe first years of life, the higher parts ofthe brain become organized and morefunctionally capable. Brain growth anddevelopment is profoundly “front loaded”such that by age four, a child’s brain is90% adult size! This time of greatopportunity is a biological gift. In anurturing environment, a child can growto achieve the full potential pre-ordainedby underlying genetics. We can promotethis by fostering conditions of optimaldevelopment.www.lfcc.on.ca

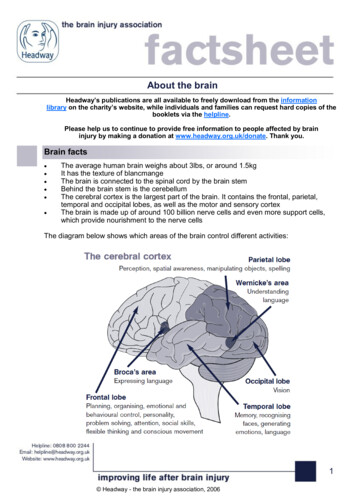

T H EL E C T U R ES E R I E SOptimal DevelopmentA child is most likely to reach her fullpotential if she experiences consistent,predictable, enriched, and stimulatinginteractions in a context of attentiveand nurturing relationships. Aidedby many relational interactions –perhaps with mother, father, sibling,grandparent, neighbour and more –young children learn to walk, talk,self-regulate, share, and solve problems.Every child will face new andchallenging situations. These stressinducing experiences per se need notbe problematic. Moderate, predictablestress, triggering moderate activation ofthe stress response, helps create acapable and strong stress-responsecapacity, in other words, resilience. Thefirst day of kindergarten, for example, isstressful for children. Those embeddedin a safe and stable home baseovercome the stress of this newsituation, able to embrace thechallenges of learning.Disrupted DevelopmentWhile most children experience safeand stable upbringings, we know all toowell that many children do not.The very biological gifts that makeearly childhood a time of greatopportunity also make children veryvulnerable to negative experiences:inappropriate or abusive caregiving, alack of nurturing, chaotic andcognitively or relationally impoverishedenvironments, unpredictable stress,persisting fear, and persisting physicalthreat. These adverse effects could beassociated with stressed, inexperienced,ill-informed, pre-occupied or isolatedcaregivers, parental substance abuseand/or alcoholism, social isolation, orfamily violence. Chronic exposure ismore problematic than episodicexposure.In the most extreme and tragic casesof profound neglect, such as whenchildren are raised by animals, thedamage to the developing brain – andchild – is severe, chronic, and resistantto interventions later in life.A hyperarousal response is morecommon in older children, males, andin circumstances where trauma involveswitnessing or playing an active role inthe event.The dissociative response involvesavoidance or psychological flight,withdrawing from the outside worldand focusing on the inner. The intensityof dissociation varies with the intensityThese images illustrate the negative impact ofof the trauma. Children may beneglect on the developing brain. The CT scandetached, numb, and have a low hearton the left is from a healthy three-year-oldrate. In extreme cases, they maywith an average head size. The image on theright is from a three-year-33old child suffering withdraw into a fantasy world. Adissociative child is often compliantfrom severe sensory-deprivation neglect. Thischild’s brain is significantly smaller and has(even robotic), displays rhythmic selfabnormal development of cortex.soothing such as rocking, or may faint iffeeling extreme distress. Dissociation isThe Adaptivemore common in young children,females, and during traumatic eventsResponse to Threatcharacterized by pain or inability toWhen a child is exposed to any threat,escape.his brain will activate a set of adaptiveDifferential “State”responses designed to help him survive.There is a continuum of adaptiveReactivityresponses to threat and differentA child with a brain adapted for anchildren have different adaptive styles.environment of chaos, unpredictability,Some use a hyperarousal response (e.g.,threat, and distress is ill-suited to thefight or flight) and some a dissociativemodern classroom or playground. It isresponse (essentially “tuning out” thean unfortunate reality that the veryimpending threat). In most traumaticadaptive responses that help the childevents, a combination of the two issurvive and cope in a chaotic andused.unpredictable environment puts thechild at a disadvantage when outsidethat context.Traumatic EventWhen children experience repetitiveactivation of the stress responseProlongedsystems, their baseline state of arousal isaltered. The result is that even whenAlarm Reactionthere is no external threat or demand,they are physiologically in a state ofalarm, of “fight or flight.” When aAltered Neuralstressor arises, perhaps an argumentSystemswith a peer or a demanding school task,they can escalate to a state of fear veryA child adopting a hyperarousalquickly. When faced with a typicalresponse may display defiance, easilyexchange with an adult, perhaps amisinterpreted as wilful opposition.teacher in a slightly frustrated mood,These children may be resistant orthe child may over-read the non-verbaleven aggressive. They are locked incues such as eye contact or touch.a persistent “fight or flight” state.Compared to their peers, therefore,They often display hypervigilance,traumatizedchildren may have lessanxiety, panic, or increased heart rate.capacity to tolerate the normal

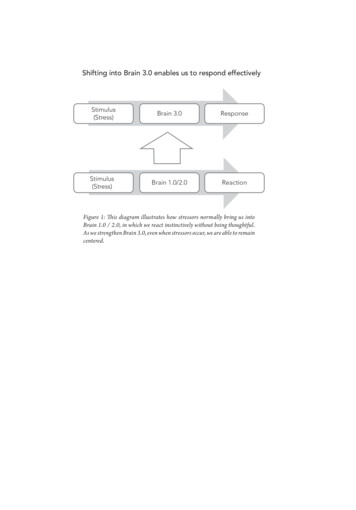

demands and stresses of school, home,and social life. When faced with achallenge, for example, resilient childrenare likely to stay calm. Normal childrenin the same situation may becomevigilant or perhaps slightly anxious.Vulnerable children will react with fearor terror.Fear Changesthe Way We ThinkChildren in a state of fear retrieveinformation from the world differentlythan children who feel calm.In a state of calm, we use the higher,more complex parts of our brain toprocess and act on information. In astate of fear, we use the lower, moreprimitive parts of our brain. As theperceived threat level goes up, the lessthoughtful and the more reactive ourresponses become. Actions in this statemay be governed by emotional andreactive thinking styles.As noted above, when childrenexperience repetitive activation of thestress response systems, their baselinestate of arousal is altered. Thetraumatized child lives in an arousedstate, ill-prepared to learn from social,emotional, and other life experiences.She is living in the minute and may notfully appreciate the consequences ofher actions. Add alcohol to the mix, orother drugs, and the effect is magnified.Decreasingthe Alarm StateIt is important to understand that thebrain altered in destructive ways bytrauma and neglect can also be alteredin reparative, healing ways. Exposingthe child, over and over again, todevelopmentally appropriateexperiences is the key. With adequaterepetition, this therapeutic healingprocess will influence those parts of thebrain altered by developmental trauma.Unfortunately most of our therapeuticefforts fall short of this.We can also be good role models: inall our interactions with children we canbe attentive, respectful, honest, andcaring. Children will learn that not alladults are inattentive, abusive,unpredictable, or violent.It is paramount that we provideenvironments which are relationallyenriched, safe, predictable, andnurturing. Failing this, our conventionaltherapies are doomed to be ineffective.If a child is in a therapeuticrelationship, we can help him betterunderstand the feelings and behavioursthat are the legacy of abuse andneglect. Information helps. Atraumatized child may act impulsivelyand misunderstand why – perhapsbelieving she is stupid, bad, selfish ordamaged. We can also teach adults in achild’s life about how traumatizedchildren think, feel, and behave.Among the possible therapeuticoptions to help maltreated andtraumatized children are cognitivebehavioural therapy, individual insightoriented psychotherapy, family therapy,group therapy, play or art therapy, eyemovement desensitization and reprogramming (EMDR), andpharmacotherapy. Each of these hassome promising results and manydisappointments.Therapy with maltreated children isdifficult for many reasons. In the longterm, the wisest strategy is to preventabusive, neglectful, and chaoticcaregiving. In that way, fewer childrenwill require therapy.Preventionand SolutionsWe are the product of our childhoods.The health and creativity of acommunity is renewed each generationthrough its children. The family,community, or society that understandsand values its children thrives; thesociety that does not is destined to fail.To truly help our children meet theirpotential, we must adapt and changeour world. Some ways to do this follow:1) Promote education aboutbrain and child developmentWe must as a society provideenriching cognitive, emotional, social,and physical experiences for children.The challenge is how best to do this.Understanding fundamental principlesof healthy development will move usbeyond good intentions to help shapesensitive caregiving in homes, earlychildhood settings, and schools.Research is key. Public education mustbe informed by good research and bythe implementation and testing ofeducational and intervention programs.An important component of publicunderstanding must be awareness ofthe power of the media over children.What to do? Integrate key principlesof brain development, childdevelopment and caregiving into publiceducation. We presently require moreformal education and training to drive acar than to be a parent. More researchin child development and basicneurobiology is needed to guidesensible changes in policy, programsand practice.2) Respect the gifts of early childhoodEnriching environments do exist.Many homes and high-quality, earlychildhood educational settings providethe safe, predictable, and nurturingexperiences needed by young children.Unfortunately, we often squander thewonderful opportunity of earlychildhood.At a time when the brain is mosteasily shaped – infancy and earlychildhood – we spend the fewest publicdollars to influence brain development.However, expenditures on programsdesigned to change the braindramatically increase for later stages ofdevelopment (e.g., mental health,substance abuse or juvenile justiceinterventions).Investing in high-quality earlychildhood programs could avoid theexpensive, often inefficient orineffective, interventions required later.Unfortunately, these expensiveinterventions can be reactive,fragmented, chaotic, disrespectful and,sadly, sometimes traumatic. Our publicsystems may recreate the mess that

many abused and neglected childrenfind in their families.What to do? Innovative and effectiveearly intervention and enrichmentmodels exist. Integrate them into thepolicy and practices in your community.Help the most isolated, at-risk youngparents connect with communityresources, both pre-natally and postpartum. Demand and support highstandards for child care, foster care,education, and child protective service.BrainʼsCapacityto ChangeAge 03lSpending onPrograms to“Change theBrain”6l12l20.Mental Health.Juvenile Justice.Headstart.Public Education.Substance Abuse Tx.3) Address the relationalpoverty in our modern worldWe are designed for a different worldthan we have created for ourselves.Humankind has spent 99 percent of itshistory living in small, intergenerationalgroups. A child’s day brought manyopportunities to interact with thevariety of caregivers available to protect,nurture, enrich, and educate. But, therelational landscape is changing.Today, with our smaller families, wehave less connection with extendedfamilies and fewer opportunities tointeract with neighbours. Childrenspend a great deal of time watchingtelevision. While we in the westernworld are materially wealthy, we arerelationally impoverished. Far too manychildren grow up without the numberand quality of relational opportunitiesneeded to organize fully the neuralnetworks to mediate important socioemotional characteristics such asempathy.What to do? Increase opportunitiesfor children to interact with others,especially those who are good rolemodels. Simple changes at home andschool can help: limiting television use,having family meals, playing gamestogether, including neighbours,extended family and the elderly in thelives of children, and bringing retiredvolunteers into schools to create multiage educational activities.teacher interactions. Specific waysto foster strengths at home andat school are suggested on TheChildTrauma Academy’s website:www.ChildTrauma.org4) Foster healthydevelopmental strengthsThe effects of maltreating andtraumatizing children have a compleximpact on society. Because our speciesis always changing, betterunderstanding of these issues wouldhelp us develop more effectivesolutions.The human brain is designed for lifein small, relationally healthy groups.Law, policy and practice that arebiologically respectful are moreeffective and enduring. Unfortunately,many trends in caregiving, education,child protection and mental health aredisrespectful of our biological gifts andlimitations, fostering poverty ofrelationships. If society ignores the lawsof biology, there will inevitably beneurodevelopmental consequences. If,on the other hand, we choose tocontinue researching, educating andcreating problem-solving models, wecan shape optimal developmentalexperiences for our children. The resultwill be no less than a realization of ourfull potential as a humane society.Certain skills and attitudes helpchildren meet the inevitable challengesof life. They may even inoculate childrenagainst the adverse effects of violence.A child who develops six core strengthswill be resourceful, successful in socialsituations, resilient, and may recoverquickly from stressors and traumaticincidents.When one or more core strengthsdoes not develop normally, the childmay be vulnerable (for example, tobullying and/or being a bully) and maycope less well with stressors. Thesestrengths develop sequentially duringthe child’s life, so every year bringsopportunities for their expansion andmodification.What to do? The major providersof early childhood experiences areparents. Supporting and strengtheningthe family will increase the likelihoodof optimal childhood experiences.Also important will be peer andDr. Bruce Perry’sConclusionSix Core Strengths for Children:A Vaccine Against ViolenceATTACHMENT:being able to form and maintain healthy emotionalbonds and relationshipsSELF-REGULATION:containing impulses, the ability to notice and controlprimary urges as well as feelings such as frustrationAFFILIATION:being able to join and contribute to a groupATTUNEMENT:being aware of others, recognizing the needs,interests, strengths and values of othersTOLERANCE:understanding and accepting differences in othersRESPECT:finding value in differences, appreciating worthin yourself and othersFor more information on the Six Core Strengths, visit the “Meet Dr. Bruce Perry”page at rry

Margaret Norrie McCainThe HonourableMargaret N. McCain wasco-chair with Dr. FraserMustard of the highlyregarded Early YearsStudy: Reversing the RealBrain Drain (1999) and isthe Children's Championat Voices for Children.Among her manyaccomplishments, she isa founding member ofthe Muriel McQueenFergusson Foundation inNew Brunswick whosemission is the eliminationof family violencethrough public educationand research.The Lecture SeriesI n September, we held the first of an annual series of lecturesaddressing topics of interest shared by Margaret and ourCentre, such as the early years and the effects of violence onchildren. All proceeds go to the Centre's Upstream Endowmentcampaign. We are delighted that Margaret has agreed to lendher name to our new lecture series. We greatly admire herdedication to children’s interests. We are also pleased that Dr.Bruce Perry agreed to be the inaugural speaker. An audience ofover 300 watched his lecture at the London Convention Centre.His approach is in harmony with our own in many ways: beginearly, apply a developmental framework, understand howchildren cope with adversities, support caregivers to supportchildren, and help professionals understand how children think,feel and learn. For those not able to join us for the inaugurallecture, we are providing here a summary of Dr. Perry’s talk. Wehope you can join us at the next lecture.Linda BakerPh.D., C.Psych., Executive DirectorCentre for Children & Families in the Justice System.I am delighted that Dr. Bruce Perry was invited to give theinaugural Margaret McCain Lecture because he is a personwhose work I have long admired. His research and writingon the effects of family violence on children have had anenormous influence on me. In fact, they led to my decisionto focus my time and energy on early child development.Dr. Perry should be listened to by all politicians and policymakers at the highest levels. The information he presents ispowerful and irrefutable and it could change dramaticallythe lives of children and families.Margaret N. McCainMargaret is seenhere betweenDr. Peter Jaffeand Dr. Linda Baker.a Note from the Series EditorResearchers repeatedly find statisticalcorrelations between living with violence– at home and in the community – andproblematic outcomes in children. Themost sophisticated studies show us howthe correlations are mediated andmoderated by factors themselvescorrelated with violence, includingeconomic poverty, child maltreatment,emotional and physical neglect, parentalsubstance abuse, parental stress, andparental mental illness.These large studies prove what front-lineworkers already know: children living withadult domestic violence rarely experienceviolence as the only life adversity. At theCentre, we call this the “adversity package”,a term used by Dr. Robbie Rossman.Dr. Perry calls it the “malignantcombination of experience”.Simply put, the more obstacles in frontof a child, the harder time he or she hasnavigating the journey down the roadof childhood, especially if progress isjudged against peers racing forwardunencumbered by adversities What causallylinks the “adversity package” and poor childoutcome? What mechanism or mechanismsis at work to reduce a child’s chances forsuccess in life?Finding those mechanismsis the key to designingeffective prevention andintervention strategies.Some observers focus on learningand modelling, while others seepsycho-dynamic factors as important.Feminist thought and gender analysishave had a great impact on our collectiveunderstanding of violence. Each view hasdifferent implications for intervention.Dr. Perry posits another causal mechanism,hidden from view deep inside the brain.Traumatic features of a violent world –noise, chaos, fear, isolation, deprivation,neglect – alter the developing brain offetuses, babies, and toddlers. Their brainsadapt appropriately to toxic environments,but these adaptations are at odds withrequirements for school and socialrelationships. These children are primedto survive their world, leaving themill-prepared to achieve their full potentialin our world. This document is a briefsummary of Dr. Perry’s stimulatinglecture, pointing readers to othersources of information.Alison Cunningham, M.A.(Crim.),Director of Research & Planning,Centre for Children & Families in the Justice System

Bruce PerryM.D., Ph.D., Senior Fellow,Child Trauma Academy,Houston, TexasDr. Perry served as the Thomas S. Trammel Research Professor of Child Psychiatry atBaylor College of Medicine and Chief of Psychiatry at Texas Children’s Hospital inHouston, from 1992 to 2001. Dr. Perry consults on incidents involving traumatizedchildren, including the Columbine High School shootings, the Oklahoma City Bombing,the Branch Davidian siege and the September 11 terrorist attacks. He has served as theDirector of Provincial Programs in Children’s Mental Health for Alberta, and is the authorof more than 250 scientific articles and chapters. He is an internationally recognizedauthority in the area of child maltreatment and the impact of trauma and neglect on thedeveloping brain. Dr. Perry attended medical and graduate school at NorthwesternUniversity and completed a residency in general psychiatry at Yale University School ofMedicine and a fellowship in Child an Adolescent Psychiatry at the University of Chicago.Readers interested in additional material by Dr. Perry can visit the Child Trauma Academy at:www.childtrauma.org or www.childtraumaacademy.com (with free on-line courses)Bruce D. Perry (2004). Maltreated Children: Experience, Brain Development, and the Next Generation.New York: W.W. Norton.Additional Resources Recommended by Dr. PerryMarian Diamond & Janet Hopson (1999). Magic Trees of the Mind: How to Nurture Your Child's Intelligence,Creativity and Healthy Emotions from Birth Through Adolescence. Plume Books.Robin Fancourt (2001). Brainy Babies: Build and Develop Your Baby’s Intelligence. Penguin.Alison Gopnik, Andrew N. Meltzoff & Patricia Kuhl (2000). The Scientist in the Crib: Minds, Brainsand How Children Learn. Perennial.Ronald Kotulak (1997). Inside the Brain: Revolutionary Discoveries of How the Mind Works.Andrews McMeel Publishing.Web SitesAttachment Parenting International: www.attachmentparenting.orgSociety for Neuroscience: www.sfn.orgNational Association to Protect Children: www.protect.orgCalifornia Attorney General’s Safe from the Start Initiative:Reducing Children’s Exposure to Violence: www.safefromthestart.orgT H EL E C T U R ES E R I E Sis an initiative of:The Centre for Children & Families in the Justice System200 - 254 Pall Mall St. LONDON ON N6A 5P6 CANADAwww.lfcc.on.caProceeds fromThe Margaret McCainLecture Seriesgo to theUpstream Endowment.The Centre is a non-profit organization dedicated to helping children and families involvedwith the justice system, as young offenders, victims of crime or abuse, the subjects ofcustody/access disputes, the subjects of child welfare proceedings, parties incivil litigation, or as residents of treatment or custody facilities.For more information,including directions on howto make donations, visitWe help vulnerable children achieve their full potentials in life, through professional training,resource development, applied research, public education, community collaborationand by providing informed and sensitive clinical services.www.lfcc.on.ca/upstream.htmlRevenue Canada Charitable Registration No. 12991 5153 RR0001 2005 CENTRE FOR CHILDREN AND FAMILIES IN THE JUSTICE SYSTEM

Sharing ideas to help children thrive www.lfcc.on.ca Inaugural Lecture by Bruce D. Perry,M.D., Ph.D. Maltreatment and the Developing Child: How Early Childhood Experience