Transcription

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6AMAZON ON FIREDEFORESTATION AND FIREIN INDIGENOUS LANDSMartha Fellows, Ane Alencara, Matheus Bandeiraa, Isabel Castroa & Carolina Guyotaa. Amazon Environmental Research Institute.E-mail: martha.fellows@ipam.org.brIntroductionIndigenous peoples play a key role in forestconservation (Walker et al., 2020). Yearafter year, the balance created by thetraditional use of natural resources and theprotection of territory, active or innate, limitstransformation of the landscape and allowsecosystem services to be maintained.Even the use of fire by certain Indigenouspopulations, especially those living insavanna vegetation areas (Falleiro etal., 2016), to manage their production,hunting, and natural resources occurs ona small-scale (Falleiro, 2011; Welch et al.,2013). It is false, therefore, that it is theIndigenous peoples who are responsible forthe increase in fire observed throughout theAmazon region in 2019 and 2020.However, even though a humid tropical forestsuch as the Amazon is not an environmentwhere fire naturally spreads (Thonicke et al.,2001), and fire use by Indigenous peoplesis uncommon outside the transition areaof the Amazon and Cerrado, and in thesavannah (Falleiro et al., 2016), forest fireshave intensified in recent years (Brando et al.,2020), driven mainly by land use change andclimate change (Silvério et al., 2013).ipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaHighlights Indigenous lands are among theland categories with the leastdeforestation and fire in theAmazon; In 2020, only 3% of LIs areresponsible for 70% of thedeforestation and 50% of the fires,being tied to illegal activities byexternal agents; The area irregularly registered asprivate property within LIs increased55% between 2016 and 2020, andthe number of Rural EnvironmentalRegistry (CAR) records grew 75%; Hotspots in areas illegally registeredthrough CAR within LIs increased105% between 2016 and 2019;outside of such areas, the increasewas 33%; Deforestation was 2.6 times higherand fire was 2.2 times higher within5 km of illegal mining operations inthe LIs with this activity, comparedto areas outside this radius ofinfluence.ipam amazonia1IPAMclimaipam.org.br

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6The effect of fire is especially worrisome inthe current context, as smoke aggravatesthe already critical scenario of thepandemic caused by the new coronavirus(Moutinho et al., 2020), leading torespiratory diseases. The situation is evenmore complex when it comes to Indigenouspeoples (Fellows et al., 2020).This technical note looks closely at thedynamics of deforestation and fire inIndigenous lands (LIs) in the Amazonbetween 2016 and 2020, to understand howthe recent spike in these rates is reflected inthese areas, and how illegal activities, suchas land-grabbing, fuel this picture.T h e re s u l t s c a n s u p p o r t a c t i o n s b ygovernment agencies that guarantee theintegrity of these traditional territoriesand respect for the more than 430,000Indigenous peoples (IBGE, 2010) in theregion, who today face the negativeconsequences of actions by third parties intheir communities (COIAB, 2020).MethodStudy area and data sourcesTo understand how illegal activities affectthe lives of Indigenous peoples living in theirtraditional territories in the Brazilian Amazon,the records of the Rural EnvironmentalRegistry (CAR) which showed overlappingwith Indigenous lands (LIs) were analyzedas an indication of land grabbing andillegal mining, as well as the occurrence ofdeforestation and hotspots in the LIs of theregion.The source of the CAR was the National Ruralipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaEnvironmental Registry System (SICAR)database, extracted for February 2020from the Brazilian Forest Service websitein August 20201. The data on illegal miningwere obtained for 2020 from the AmazonSocio-environmental Information Network(RAISG) in February 20212. The boundaries ofthe Indigenous lands were obtained from theNational Indian Foundation (FUNAI), updatedup to 20203. The geographic limits of theother land categories, such as conservationunits, including environmental protectionareas, rural properties and settlements,undesignated public forests, and areaswithout registration information were usedas described in Alencar et al (2020). Fordeforestation data, DETER alerts wereextracted from the National Institute forSpace Research (INPE) from 2016 to 20204.For fire occurrence, hotspots were extractedfrom INPE’s Burning and Forest FireMonitoring Portal database in January 20215.Dynamics of deforestation and fire inIndigenous lands with overlapping CARentriesThe analysis of the dynamics ofdeforestation and fire in the Indigenouslands in relation to the CAR was done usingthe following steps: (1) the CAR databasewas treated so as to eliminate the overlapbetween records, without eliminating thescope of the registered area, thus avoidingduplicate results; (2) to calculate the areaof CAR overlap in LIs, the overlaps betweenCAR records were also removed from theanalysis, in addition to the overlaps of theCAR perimeter with conservation units andquilombola areas (CAR-PCT), thereforeconsidering the overlaps between LIs andCAR settlement and individual CARs; (3)ipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br1. CAR databaseavailable at https://www.car.gov.br/publico/imoveis/index.2. RAISGdatabase availableat em /#!/download.3. LIs limitsavailable at http://www.funai.gov.br/index.php/shape.4. DETERdatabase availableat http://terrabrasilis.dpi.inpe.br/downloads.5. Hotspotsdatabase availableat .2

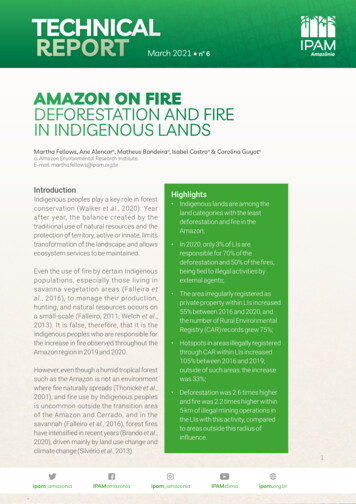

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6the database was cross-referenced withthe limits of the Indigenous lands, thusindicating the areas within these landswhich did and did not overlap with the CAR;(4) only the area of the CAR that overlappedwith the Indigenous land was analyzed, thatis, the records that exceeded the limits of theIndigenous land were cut out and removedfrom the analysis; and (5) these data werecombined with the data on deforestationand hot spots from 2016 to 2020, in orderto generate annual statistics of forest lossand fire for the Indigenous lands with andwithout CAR overlapping.Deforestation and fire in LIs with thepresence of illegal miningThe quantity of existing illegal miningwas calculated for each Indigenous land.For all the mines overlapping with theIndigenous lands, a radius of five kilometerswas applied, which served to define thearea of direct influence of this activity onthe registered deforestation. These areaswere superimposed on deforestationand hotspots from 2016 to 2020, thusgenerating annual data for the activity’ssurrounding.ResultsIndigenous lands in the Amazon havehistorically had low rates of deforestationand fire rates among land tenure categoriesin the region. This is an indication that theallocation of these areas to traditionalpopulations, as governed by the BrazilianConstitution, has a positive effect onenvironmental and climate preservation,with benefits that are shared by all Brazilians(Ricketts et al., 2010; Soares-Filho et al.,2010) in addition to their social, cultural andhistorical importance.In 2019 and 2020, deforestation increased inthe region (Silva Junior et al., 2021), and LIsaccounted for the smallest share: in 2019,they accounted for 5% of all deforestation;in 2020, the rate was 3% of the total (figures1 and 2).The limited use of fire is another indicationof the level of protection that Indigenouslands offer to the forest. It is among thethree land categories that recorded thefewest hotspots in 2019 (7% of the total) and2020 (8%), behind only conservation unitsand environmental protection areas (APA),and far behind settlements, rural propertiesand undesignated public forests (figures 1and 2).3ipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6Figure 1. Percentage of deforestation and fire in Indigenous lands compared to other land categoriesfor the years 2019 and 2020. Source: IPAM, based on data from INPE.Figure 2. Annual distribution of deforestation and fire on Indigenous lands in the Amazon between2016 and 2020 and proportion of deforestation and fire relative to the region’s total. Source: IPAM , basedon data from INPE.4ipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6On their own, these numbers would besufficient to invalidate the mistaken ideathat Indigenous peoples are responsiblefor the fires in the Amazon. However, amore detailed analysis of 2020 still showsthat a good part of what happens in theIndigenous lands is not related to the wayof life of the original populations, but ratherto invasions and the improper use of theirterritories by third parties.The sub-basin of the Xingu, the north ofRoraima, and the border between Paráand Amazonas contain the LIs with thehighest number of hotspots in 2020 (figure4). Many of these are located in or containlarge areas of savanna vegetation, whichenable the spread of fire (Pivello, 2011), anindication that helps to explain why the LIswith more fire do not necessarily have moredeforestation.Of the 330 Indigenous lands analyzed, onlyten of them, or 3%, were responsible for70% of the deforestation and 51% of thefire in 2020 (figure 3 and 4). The Indigenouslands with the highest rates of deforestationare in the arc of deforestation, which runsfrom Rondônia, through Mato Grosso andup the central-western part of Pará, mainlyin the Xingu basin (figure 3). Among themost affected territories are the Apyterewa,Trincheira Bacajá, Cachoeira Seca, Ituna/Itatá, and Kayapó Indigenous Lands, thefive that recorded the most deforestation in2020 (figure 3). These LIs are located in theregion of the middle Xingu River, in Pará, andare undergoing invasions by external agentsthat range from small producers to largelandowners; some even appear on the list ofLIs with the most illegal mining.Among the LIs that presented a high numberof hotspots and that have large patchesof savanna vegetation are Raposa Serrado Sol and São Marcos, in Roraima, with83% savanna. The Indigenous Parks ofTumucumaque (AP, PA) and Xingu (MT),and the Kayapó (PA), Munduruku (PA) andCapoto/Jarina (PA) Indigenous lands alsohave large areas of savanna vegetation intheir center, varying from 4% to 15% of theseterritories and being where fire is usuallyconcentrated.ipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaThe Apyterewa (PA), Andirá-Maraú (AM, PA)and Cachoeira Seca (PA) Indigenous lands,which complete the list of the ten territorieswith the highest number of hotspots in2020, do not have significant areas of nonforested vegetation, and the fire inside themis mainly related to deforestation.ipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br6. Fire is presentin the savannavegetationformation (Mistryet al., 2005), butland use andclimate changesare increasingits intensity andimpact (Nóbregaet al., 2019).The Indigenouspeoplesmanagement ofthe areas is crucialto maintain theirtraditional way ofliving, but also forthe ecosystembalance in theregion (Balee,2006). 5

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6Figure 3. Indigenous lands with largest deforested area (ha) in 2020. Source: IPAM, based on data from INPE.Figure 4. Indigenous lands with the most hotspots in 2020. Source: IPAM , based on data from INPE.6ipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6Several vectors can explain the distributionand concentration of deforestation andfire in the Indigenous lands of the Amazon.Some of them indicate the pressure onIndigenous lands, with illegal occupationand land grabbing.The CAR, a self-repor ting registry ofrural properties, represents one of theseimportant indicators of pressure. Between2016 and 2020, the area improperlyregistered within Indigenous lands in theAmazon increased by 55%: if before therewere about 2.3 million hectares declaredas private property in lands designatedfor Indigenous peoples, in five years thisarea jumped to 3.57 million ha (figure 5A) -almost six times the size of Brazil’s FederalDistrict. The number of registrationsincreased 75% in the same period, from3,517 to 6,170 (figure 5B).Only 3% of the CAR’s overlap with LIsoccurred in settlement projects. In 2020,the vast majority (75%) of CARs overlappingwere small properties, with less than 100 ha,which together account for only 2.24% of theirregularly registered area. Large properties,with more than 1,000 ha, accounted for7.11% of the registrations, or 439 records,but together they represented 88% of theoverlapping of CARs with LIs, around 3.15million ha (figures 5A and 5B) - an area largerthan that of the State of Sergipe.Figure 5. Area and quantity of CAR entries registered in overlap with Amazon Indigenous landsfrom 2016 to 2020. Source: IPAM, based on data from SICAR/SFB.Pará, Mato Grosso and Amazonas arethe States most affected by the improperregistration of CARs (figure 6). The illegaloccupation assumes very high proportionsin some cases. Ituna/Itatá (Pará State)has 94% of its area with overlapping CARsand is among the Indigenous lands thatipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniasuffered the most deforestation in 2020.It is the only one among the ten mostaffected that is under study, with restrictedland use, which reinforces the need toadvance in the approval process. But,besides this extreme case, other Indigenouslands also present many overlappingipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br7

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6CARs, despite being declared or approvedterritories, as is the case of Seruini/Marienê(Amazonas), Manoki (Mato Grosso),Riozinho (Amazonas), and Kawahiva do RioPardo (Mato Grosso), which also presentedextensive areas that overlap with the CARregister ( 43%) (table 1). Trombetas/Mapuera (Amazonas, Pará and Roraima), inthe northern channel of the Amazon River,and Apiaká do Pontal and Isolados (MatoGrosso) stand out for the size of the arearegistered as private.Figure 6. Indigenous lands with largest area of overlap with CAR entries in 2020. Source: IPAM, basedon SICAR/SFB data.Table 1. Characteristics of the 10 Indigenous lands in the Amazon with the largest area of CARoverlap in 2020. Source: IPAM, based on data from SICAR/SFB, INPE and Funai.RankingLI NameStateStatusLI area(in ha)Área of CARoverlap (in ha)% of LI areaoverlapping withCAR1Trombetas/MapueraAM, PA, RRLegalized3,970,078544,85414%2Apiaká do oAMDeclared366,167231,77763%4KayabiMT, PAApproved1,053,923177,41417%5Kawahiva do ed250,706138,32255%7Ituna/ltatáPAUnder study142,527134,11294%8Nhamundá/MapueraAM, PALegalized1,049,011129,80612%9Seruini/ MarieneAMLegalized144,886114,01879%10Cachoeira SecaPALegalized732,447109,56915%8ipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6The relationship between landmisappropriation and deforestation is clear,and has intensified in the last two years.The percentage of deforestation in areaswith CAR inside the LIs reached a peak in2019, accounting for 41% of all land thatwas cleared on Indigenous lands (figure 7A)- between 2016 and 2019, the deforestationrate grew by 1,169% in the overlappingareas, while in the external areas withoutCAR, the increase was 651%. In 2020, therate of deforestation in CAR areas fell to23% of all the deforestation recorded in theLIs with overlap, but it is still higher than inprevious years.Some of the LIs with more CAR overlap areaalso emerged on the list of Indigenous landswith the highest deforestation rate in 2020,such as Ituna/Itatá and Cachoeira Seca,both in Pará (figure 3).Regarding fire, nine percent of the hotspotsrecorded in the Indigenous lands happenedin areas with CAR overlap in 2019, and sixpercent in 2020. The rates are similar to theother three years analyzed (4% in 2016, 6%in 2017, and 9% in 2018), indicating thatfire in LIs depends on factors other thandeforestation, such as external ignitionsources entering the territories, large areasof savanna vegetation in some of them, asmentioned previously, and very dry weatherin certain years, which can cause fire tospread, even through the use in Indigenousproductive practices, if there are not verystrict control measures.Despite this low average, the hotspotswithin the CAR overlap area increased 105%between 2016 and 2020, while the averageincrease for the rest of the Indigenouslands was 3.2 times lower, with a 33%growth between these two years. Theseresults corroborate the argument that theCAR, despite having been created as atool for environmental regularization, hasbeen widely used to justify illegal activities,leading to forest clearing in the Indigenouslands.Figure 7. Dynamics of deforestation and fire in LIs between 2016 and 2020 in the area of overlapwith the CAR, and (B) percentage of deforestation and fire in LIs registered in the area of overlapwith the CAR. Source: IPAM, based on data from INPE and SICAR/SFB.ipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br9

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6Deforestation and fire in areas near illegalmines in LIsThe occurrence of illegal mining alsorepresents an important pressure vectorthat can result in deforestation and fire.Some of the Indigenous territories standout for the historical presence of miningactivities, as is the case of the YanomamiIndigenous Land, between Roraima andAmazonas (Ramos, 1993), and the RaposaSerra do Sol IL, in Roraima (Voivodic etal., 2018). The three neighboring basinsof the Xingu (Schwartzman et al., 2013),Tapajós and Madeira are also marked bythe presence of illegal mining (Figure 8). Inthese basins, it is important to emphasizethe role of mining, especially of gold, in theKayapó, Baú, Munduruku, Apyterewa, andTrincheira Bacajá LIs, all in Pará. The lasttwo are among the ten LIs with the most fireand deforestation in 2020 (figures 3 and 4).Figure 8. Indigenous lands with highest rates of illegal mining in 2020. Source: IPAM, based on RAISGdata.In the area of influence of illegal mining,defined by a radius of five km from its centralpoint, deforestation and the number ofhotspots were higher overall in 2019 and2020 than in the other years analyzed. In thecase of deforestation, the area of forestcleared in the vicinity of mines withinIndigenous lands was on average 142%greater in 2019/2020 than in the first threeyears of the analysis (2016 to 2018). Thenumber of hotspots was also higher in 2019and 2020 compared to the other years - withthe exception of 2017, a year with many firesin the Amazon caused by extreme drought(Brando et al. 2020) (figure 9). Comparedto areas outside the area of influence ofillegal mining, in the LIs that have illegalmining, deforestation and fire were 2.6times and 2.2 times higher, respectively,within 5 km, which shows the concentratedimpact of this illegal activity.10ipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6Figure 9. (A) Area deforested and (B) number of hotspots in the area of influence of the mines(5km) between 2016 and 2020. Source: IPAM, based on data from INPE and RAISG.Discussionthemselves almost 3 million hectares.The invasion of Indigenous lands inthe Amazon has intensified and, with it,increased deforestation and fire. If beforethe correct destination of these territories tothe original peoples brought at its core therecognition of their fundamental rights overthe lands they traditionally occupied, whichtranslates into environmental conservation,today the illegal occupation of these landsand other illegal activities threaten theirintegrity and the safety of those who livethere.This is a movement observed in the majorityof the Indigenous lands in the region (83%)- of the 330 analyzed in this technical note,275 have unauthorized CARs within them.In some cases, the abuse is overt and clear,as is the case for lands that had most oftheir areas allotted in the National RuralEnvironmental Registry System by privateindividuals, as if they were “no man’s land”,or for the 439 CARs with more than 1,000hectares each, which irregularly take foripam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaThe weakening of Indigenous policies andinspection and control bodies in the lasttwo years stimulates invasions, as wellas deforestation and mining. An examplewas the attempt to split FUNAI betweenthe Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministryof Women, Family and Human Rights,an action that raised harsh criticism andresulted in the retreat of the Indigenousministry to the Ministry of Justice. Anotherunremedied blow is the budget reduction ofthe Indigenous body, which in 2019 lost 23%of its budget compared to 2013, an amountthat already represented a minuscule 0.02%of the Union’s budget (INESC, 2020).The environmental agenda has also beendismantled in recent years. Part of theenforcement and control functions of theMinistry of Environment were transferredto the Ministry of Agriculture (Fearnside,2019; Ferrante and Fearnside, 2019); theresources allocated to the area were alsoipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br11

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6shrunk (INESC, 2020). These changescome in addition to government rhetoricthat attempts to discredit national researchinstitutions that are fundamental tocombating deforestation in the Amazonregion (Barretto Filho, 2020).et al., 2020), and for these territories toremain intact so as to guarantee the way oflife of Indigenous peoples, it is essential thatinvasions be quickly and efficiently curbed.In this context, some actions are urgent,among them:The publicized intention of the federalgovernment to no longer approveIndigenous lands encouraged illegalactivities and occupations, as happenedwith the Ituna/Itatá IT, which has more than90% of its area covered by CAR entries in anirregular manner and appears as one of themost deforested LIs in recent years. Suspension and annulment of all CARson Indigenous lands, including the banningof new registrations in these territories, withwide dissemination of these measures tosociety;In addition to these initiatives by theexecutive branch, a series of legislativemaneuvers that confront the traditional useof Indigenous lands have been encouraged,such as Bill 191, from 2020, which seeks toregulate the exploitation of mineral, hydricand organic resources in Indigenous areas.The combination of factors has led evenratified Indigenous lands, such as CachoeiraSeca and Apyterewa, also in Pará, to sufferintense external pressure.It is fundamental to remember that, inaddition to deforestation and fire, theinvasions also threaten the health andsafety of the Indigenous populations(Fellows et al, 2021, in press) by bringingdiseases into these regions, including thenew coronavirus (CIMI, 2020).In order for these territories to continue tofulfill their function as home to Indigenouspeoples in the Amazon and as importantbarriers against deforestation and fire (FAO& FILAC, 2021; Nepstad et al., 2006; Walkeripam amazoniaIPAMamazonia Respect for the International LaborOrganization (ILO) Convention 169,highlighting the rights of Indigenous peoplesto free, advanced and informed consultationregarding the use, management, andconservation of their territories; Removal of miners from Indigenouslands, socio-environmental recovery ofthe areas affected by mining activity andannulment of PL 191, from 2020, whichaims to open the Indigenous lands to anytype of economic exploitation; Creation of a buffer zone of 10 kilometersbetween Indigenous lands and areas ofmining exploration or high-impactenterprises; Technical and financial strengthening ofIBAMA and the Federal Police, includingdestruction of material, in order to bettercombat new illegal mines, remove invadersand curb illegal logging; Support for Indigenous fire brigades andprioritization of the actions of fire preventionbrigades (such as Prevfogo) in Indigenousipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br12

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6territories – such actions should be adaptedto the diverse cultural realities of the region; C re a t i o n o f a s p e c i f i c g ro u p t h a trepresses threats to the Indigenous lands,with representatives from the Indigenousorganizations and FUNAI, IBAMA, FederalPolice and Federal Public Ministry in anequal manner; and Prohibition of any illegal activity or theinstallation of high-impact enterprises inareas where autonomous peoples live involuntary isolation.AcknowledgmentsGordon e Betty Moore Foundation, Institutefor Climate and Society and Toba CapitalReferencesA L E N C A R , A . , M o u t i n h o , P. , A r r u d a , V. ,Silvério, D. Amazônia em chamas - O fogo e odesmatamento em 2019 e o que vem em 2020:nota técnica nº 3. Brasília: Instituto de PesquisaAmbiental da Amazônia. 2020. Available -2020/.BALÉE, W. The Research Program of HistoricalEcology. Annual Review of Anthropology 35:75–98, 2006. 23231.B A R R E T TO F I L H O, H.T. Bolsonaro, MeioAmbiente, Povos e Terras Indígenas e deComunidades Tradicionais. Cadernos deCampo. São Paulo, Online: 29 (2): 1–9, pe178663.ipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaBRANDO, P. M., B. Soares-Filho, L. Rodrigues, A.Assunção, D. Morton, D. Tuchschneider, E. C.M.Fernandes, M. N. Macedo, U. Oliveira, and M.T. Coe. The Gathering Firestorm in SouthernAmazonia. Science Advances 6 (2): 1–10, 2020.https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay1632.CIMI. Relatório: Violência Contra Os PovosIndígenas No Brasil - Dados De 2018. ConselhoIndigenista Missionário, 2020. Available at 018.pdf.COIAB. Plano de Ação Emergencial de CombateÀs Queimadas Ilegais Em Terras IndígenasDa Amazônia Brasileira (PACQ-COIAB).Manaus, AM: Coordenação das Organizaçõesda Amazônia Brasileira (COIAB), 2020. Availableat https://s3.amazonaws.com/appforest uf/f1600899377874x476923281789926300/planoação fogo002a.pdf.FALLEIRO, R.M.Resgate do Manejo Tradicionaldo Cerrado com Fogo Para Proteção dasTerras Indígenas do Oeste Do Mato Grosso:Um Estudo de Caso. Biodiversidade Brasileira2: 86–96, 2011. FALLEIRO, R.M., Santana, M.T., Berni, C.R. Ascontribuições do manejo integrado do fogo parao controle dos incêndios florestais nas terrasindígenas do Brasil. Biodiversidade Brasileira6 (2): 88–105, 2016. Available at hp/BioBR/article/view/655.FAO, FILAC. Forest governance by Indigenousand tribal peoples: An opportunity for climateaction in Latin America and the Caribbean. 1ª ed.Food and Agriculture Organization of the Unitedipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br13

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 6Nations (FAO), 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2953en.FEARNSIDE, P.M. Retrocessos sob o PresidenteBolsonaro: um desafio à sustentabilidadena Amazônia. Sustentabilidade InternationalScience Journal 1 (1): 38–52, 2019. Availableat http://philip.inpa.gov.br/publ livres/2019/Fearnside-Retrocessos sob o PresidenteBolsonaro-Revista Sustentabilidade.pdf.FELLOWS, M., Paye, V., Alencar, A., Nicácio, M.,Castro, I., Coelho, M. E., Moutinho, P. Não sãonúmeros, são vidas! A ameaça da covid-19aos povos indígenas da Amazônia brasileira.Brasília, DF: IPAM, 2020. Available at https://ipam.org.br/bibliotecas/nao- s- indigenas-daamazonia-brasileira/FERRANTE, L., Fearnside, P.M. Brazil’s NewPresident and ‘ruralists’ Threaten Amazonia’sEnvironment, Traditional Peoples and theGlobal Climate. Environmental Conservation,1 7 – 1 9 , 2 0 1 9 . h t t p s : // d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 1 7 /S0376892919000213.IBGE. Censo Demográfico 2010: CaracterísticasGerais Dos Indígenas. Resultados Do Universo.Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Instituto Brasileiro deGeografia e Estatística - IBGE, 2010. Available studos/indigena censo2010.pdf.INESC. O Brasil com baixa imunidade: balançodo Orçamento Geral da União 2019. Brasília,DF: Instituto de Estudos Socioeconômicos,2020. Available at .MISTRY, J., Berardi, A., Andrade, V., Krahô,T., Krahô, P., Leonardos, O. Indigenous Fireipam amazoniaIPAMamazoniaManagement in the Cerrado of Brazil: The Caseof the Krahô of Tocantíns. Human Ecology 33 (3):365–86, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745005-4143-8.MOUTINHO, P., Alencar, A., Rattis, L., Arruda, V.,Castro, I., & Artaxo, P. Amazônia em chamas 3:desmatamento e fogo em tempos de covid-19.Brasília, DF: IPAM, 2005. Available at https://ipam.org.br/bibliotecas/amazonia-em-cha- mazonia/NEPSTAD, D., S. Schwartzman, B. Bamberger,M. Santilli, D. Ray, P. Schlesinger, P. Lefebvre, etal. Inhibition of Amazon Deforestation and Fireby Parks and Indigenous Lands. ConservationBiology 20 (1): 65–73, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00351.x.N Ó B R E G A , C . , B r a n d o , P. M . , S i l v é r i o ,D.V., Maracahipes, L., Marco, P. Effectsof Experimental Fires on the Phylogeneticand Functional Diversity of Woody Speciesin a Neotropical Forest. Forest Ecology andManagement 450 (January), 2019. LO, V.R. The Use of Fire in the Cerradoand Amazonian Rainforests of Brazil: Past andPresent. Fire Ecology 7 (1): 24–39, 2011. https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0701024.RAMOS, A.R. O Papel Político Das Epidemias: OCaso Yanomami. Série Antropologia, 21, 1993.Available at: KETTS, T.H., Soares-Filho, B., Fonseca, G.B.,Nepstad, D., Pfaf, A., Petsonk, A., Anderson, A.,et al. Indigenous Lands, Protected Areas, andSlowing Climate Change. PLoS Biology 8 (3):ipam amazoniaIPAMclimaipam.org.br14

TECHNICALREPORTMarch 2021 nº 66–9, 20

ipam_amazonia IPAMamazonia ipam_amazonia IPAMclima ipam.org.br Ma n 6 TEIA RPT 4 Figure 1. Percentage of deforestation and fire in Indigenous lands compared to other land categories for the years 2019 and 2020. Source: IPAM, based on data from INPE. Figure 2. Annual distribution of deforestation and fire on Indigenous lands in the Amazon .