Transcription

Jameson, J., and Gentner, D. (2003). Mundane comparisons can facilitate relational understanding.Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society.Mundane Comparisons Can Facilitate Relational UnderstandingJason Jameson (j-jameson@northwestern.edu)Department of Psychology, Northwestern University2029 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208-2710 USADedre Gentner (gentner@northwestern.edu)Department of Psychology, Northwestern University2029 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208-2710 USAAbstractThis paper addresses the role of comparison in highlightingrelational structure. Specifically, we investigated whethereven literal similarity comparisons (where both objects andrelations match) can lead to a focus on common relations overequally suitable object matches. Whereas previous studieshave demonstrated the highlighting of relations duringanalogical comparisons (where only relations match), thestudy presented in this paper suggests that even literalsimilarity comparisons can promote relational focus. Inaddition, we explore the role of types of comparison tasks(listing commonalities or listing differences). This extensionfollows naturally from structure-mapping theory, whichpredicts that in certain cases, listing differences between twothings can actually lead to a heightened focus on the structurecommon to both.IntroductionNewton is said to have comprehended the far-reachinginfluence of gravity when it occurred to him that an applefalling from a tree was in some sense like the motion of theplanets. Einstein is said to have conceived his alternativeview of gravity when it occurred to him that a man fallingfrom the roof of a house was in some sense like an objectfreefloating in space. Both examples illustrate the power ofcomparison. To be sure, the thought processes leading tothese ideas must have been complex and diverse, but what iscommon to both is that something similar was drawn fromsomething that was prima facie very different. As such, theexamples hint at the far-reaching scope of comparison andthe perception of likeness.Examples like these have led some researchers to proposethat comparison acts to create a focus on common relationalstructure (Gentner, 1983; Gentner & Medina, 1998;Markman & Gentner, 1993b). Comparison has been shownto facilitate schema abstraction and to promote knowledgetransfer. In Gick & Holyoak’s (1983) classic studies thatinvestigated analogical transfer using the Duncker tumorproblem, people who compared two prior analogous storieswere far more likely to transfer the solution to the tumorproblem than those who read only one of the stories.Additional empirical data suggest this as well. Comparisonfacilitates transfer even to ‘hot’ interactive situations. MBAstudents who compared analogous cases depictingnegotiation strategies were more successful in extending thelearned principles to new situations than those students whodid not compare cases, but were instead given themseparately (Loewenstein, Thompson, & Gentner, 1999).Comparison has also been shown to facilitatecomprehension of spatial relations in young children.Adapting the methods from the classic studies ofDeLoache and her colleagues (e.g., DeLoache, 1987),Loewenstein and Gentner (2001) found that childrenwho directly compared similar rooms were morelikely to find an object in a similar new room thanchildren who had not compared rooms. These findingslead to the conjecture that comparison processes maybe an important route to learning deep relationalknowledge (Gentner & Medina, 1998; Gentner, 2003).In the above studies, the analogous pairs given tosubjects were designed so that only the relationalstructure matched—e.g., X-rays and an army. Thispaper asks whether the highlighting of relationalstructure can also occur in mundane overallcomparisons in which object commonalities are alsopresent. In order to be clear about what we areclaiming, consider the sentences below.a.b.c.The plumber inspected the new faucet.The plumber tested the pipes.The accountant checked the totals.The process of comparison operates over both relationsand object descriptions (Gentner, 1989; Holyoak &Thagard, 1989). Thus, the resultant common systemcan include both relations and objects in a literalsimilarity comparison, such as between a and b; or itcan contain only common relations in an analogicalcomparison, such as between a and c.The claim that comparison promotes relational focushas two forms, one obvious and one not so obvious.The obvious form is illustrated by the a and c match. Inthis case the resulting commonalties contain just therelational match. In this case, relational highlighting isnot surprising. The less obvious claim is that even inthe case of a and b, in which the commonalities includeobject descriptions as well as relational structure, theeffect of the comparison process is to heighten thefocus on common relations. This claim may at firstseem implausible: Why should common relations bemore salient than the equally preserved commonobjects?

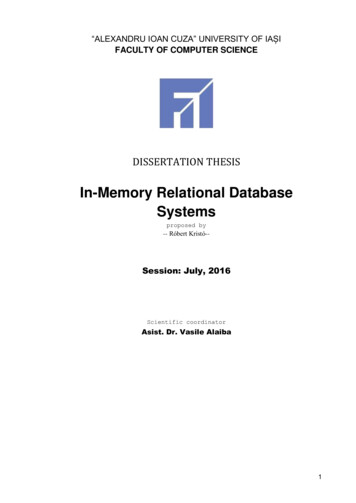

The starting point for this research comes from a theory ofsimilarity that emphasizes structural alignment and mappingof mental representations. We first briefly describe thistheory and its application to similarity comparisons. Thenwe lay out the predictions and how these tests go beyondprior demonstrations of relational focus.Similarity is like AnalogyAccording to structure-mapping theory, the core process incomparison (whether literal similarity or analogy) isaligning the representational structure of mentalrepresentations (Gentner, 1983). There is considerableempirical support for the claim that similarity involvesalignment processes akin to those involved in analogicalmapping (Markman & Gentner, 1993b; Gentner &Markman, 1997). This emphasis on the relations betweenrepresentational elements contrasts with other approaches,such as the spatial and featural models (Shepard, 1962;Tversky, 1977).The structure-mapping process model is instantiated in acomputer simulation (SME—the Structure-MappingEngine), which has successfully modeled a number ofphenomena (Falkenheiner, Forbus, & Gentner, 1989). InSME, analogical mapping occurs via a local-to-globalmatching process that begins by finding all possible localmatches among both objects and relations. It then invokestwo structural consistency constraints—one-to-one mappingand parallel connectivity—to arrive eventually at themaximal alignment of common structure. This maximalalignment is determined in part by a bias for systematicity(that is, for interconnected relations over isolated ones, andfor deeper systems of relations over shallower ones) (e.g.,Gentner & Markman, 1997). A number of studies provideevidence supporting these constraints (Gentner & Clement,1991; Gentner & Toupin, 1986).A.B.Figure 1. Sample stimuli used in a cross-mapping task(from Markman & Gentner, 1993b, study 1).In structure-mapping, because predicates that belongto connected systems are weighted more heavily thanisolated predicates, the theory predicts that relationalmatches will in general outweigh object matches. Priorevidence for this claim has utilized cross-mappingstudies, in which objects and relations are pitted againstone another (Gentner & Toupin, 1986). For example,Markman & Gentner (1993b) showed people pairs ofcross-mapped scenes like those in Figure 1. In A, a manfrom a community food bank is shown giving food to awoman; and in B, the same woman is shown givingfood to a squirrel. For each pair, subjects were asked tomatch an object in one scene—always the crossmapped object (the woman in scene A)—to itscorresponding part in the other sceneThe pairs were designed to show a strong objectmatch, and indeed subjects who simply performed aone-shot mapping task (that is, without rating thesimilarity of the scenes beforehand) tended to choosethe womanÆwoman match. However, as predicted bystructure-mapping, when subjects first rated thesimilarity of the two scenes, they mostly chose therelational match for the woman in A—namely, thesquirrel in B. This is evidence that the comparisonprocess favors finding common relational structurerather than common object descriptions when the twoare in competition.Testing relational focus – beyond crossmapping competitionTo understand how the present study goes beyond theMarkman & Gentner study, consider the followingsentences.d. The plumber pounded the jammed nozzle.e. The gushing fire hose bludgeoned the plumber.f. The plumber hammered on the faulty stopper.Like the picture pairs used in Markman and Gentner’sstudy, the sentences d and e constitute a cross-mapping.There is an obvious object mapping of “plumber” to“plumber” and “nozzle” to “fire hose”. Alternatively,one could align the central events described in the twosentences (pounded and bludgeoned), so that “plumber”in d would map to “fire hose” in e, and “nozzle” in dwould map to “plumber” in e. Thus, this pair requiresthat one choose between object matches and relationalmatches. For adults, when relational matches are pittedagainst object matches, the relational match is likely towin out. Thus, cross-mapped comparisons result inrelational highlighting.But what about the pair d and f, in which both theobjects and relations match? This research investigatesthe possibility that even in this case, common relationswill become more salient than common objects.One key line of support for the claim that evenmundane overall comparisons can lead to a focus oncommon relations comes from a set of studies byGentner & Namy (1999) that used a word-learning task

with children. In one study, 4-year-olds were presented withtriads composed of either one standard or two standards,along with two response options. For example, in one triadthe single standard was either a bicycle or a tricycle (in thesingle standard condition) or both (in the comparisoncondition). One of the response options (a pair ofeyeglasses), was perceptually similar to the standard(s) butwas from a different taxonomic category. The other option(a skateboard) was perceptually dissimilar to the standards,but was from the same taxonomic category. Children in theone-standard condition were told that the standard was a‘blicket’ in dinosaur language and asked which optionwould also be a blicket. Most of the children in thiscondition chose the perceptual response, consistent withmuch prior research (Baldwin, 1989; Imai, Gentner &Uchida, 1994; Smith, Jones, & Landau, 1992).What is more interesting, however, is that when childrenin the two-standard condition (the comparison condition)were given the parallel task, they behaved quite differently.When told that both standards were blickets, and asked tochoose the other blicket, they chose the taxonomic response.This is a counterintuitive result: when either single standardwas presented alone, the perceptually similar response waspreferred. Further, the two standards shared the sameperceptual features with each other as each did with theperceptual option. Thus, on a feature-based account,presenting the two together should have reinforced thosefeatural commonalities, thereby leading to even moreperceptual responding. However, this was not the case.When children compared the two standards, they chose thetaxonomically similar alternative. Gentner and Namyconcluded that the comparison task highlighted the commonrelational structure between the standards, and that this inturn led to the greater perceived similarity to the taxonomicresponse option.However, the conclusion that this pattern of resultsimplies highlighting of relational structure could bechallenged. The claim rests on the assumption that thesimilarity of the taxonomic members was relational. Thoughthere is evidence that people may form categories on thebasis of common relational structure (Ahn, 1999; Gentner &Medina, 1998; Kurtz & Gentner, 2001), it is still aspeculative claim. Direct evidence that comparison leads tonoticing of common relational structure is needed, withoutthe intermediate assumption that the category membersshare relational structure.The present study uses stimuli that clearly separaterelational similarity from object similarity. To accomplishthis, sentences were used as stimuli. There are severalreasons for using sentences, but the most important reason isthat they allow us to establish clear relational commonalitiesand clear surface commonalities. As in the Gentner andNamy study, we used triads in which there were tworesponse options: an object match and a relational match.ExperimentIn designing this experiment, one goal was to ensure thatparticipants engaged in an active comparison process. Priorevidence suggests that participants are more likely to arriveat a common relational abstraction for a pair of items whenthey engage in more intensive comparison processes(such as stating commonalities) than when they merelygive similarity ratings (Kurtz, Miao, & Gentner, 2000).Accordingly, participants in one comparison conditionwere asked to write out the commonalities for eachsentence pair.In addition to the commonality-listing task, we alsoincluded a difference-listing task. This group ofparticipants was asked to write out the differencesbetween sentence pairs. The task was included for tworeasons. First, it addresses a potential alternativeexplanation for the finding, should it occur, that listingcommonalities increases relational responding: namely,a kind of carryover from the first task. Suppose, as islikely on our account, that participants list relationalcommonalities for the pairs. Then a simple carryover orpriming effect might increase their subsequentlikelihood of choosing the consistent response—that is,the relationally similar response. However, if subjectswho list differences also show a shift towards relationalchoices, then we can rule out this carryoverexplanation. Second, and more importantly, thedifference-listing task provides an opportunity to testfurther predictions concerning the process of similaritycomparison.According to structure-mapping, finding differencesis normally accomplished by aligning relationalstructure and then reading off aligned differences(Markman & Gentner, 1993). For example, Gentnerand Markman (1994) found that people listeddifferences for similar objects more easily than fordissimilar objects, and listed more differences forsimilar objects than for dissimilar objects. Thissurprising result is complemented by a recent study inwhich listing the differences between similar objectsactually increased judged similarity (Boroditsky, inpress). Also, listing the commonalities among wordpairs has been shown to facilitate later listing ofdifferences for the same word pairs (Gentner & Gunn,2001).This suggests that even a comparison task thathighlights differences should also lead to alignment ofcommon structure. Thus there should be a shift towardsthe relational choice following a difference-listing taskas well as a commonality- listing task, though the effectof the difference-listing task may not be as strong.By using these sentence stimuli, we can test the claimthat comparison processes heighten attention tocommon relational structure, even when there are alsocommon aligned objects. Such a result would extendMarkman and Gentner’s finding that comparisonhighlights common relations when object and relationalmatches conflict. The main prediction, then, is thatlisting commonalities and listing differences shouldboth lead to higher rates of relational responding thanprocessing the sentences separately. An open questionis whether, as seems plausible, listing commonalitieswill lead to more relational responding than listingdifferences.

MethodParticipants Seventy-nine Northwestern studentsparticipated for partial course credit.Design The three levels of task, listing commonalities(N 26), listing differences (N 31), and ratingcomprehensibility (N 22), were run between subjects. Thepurpose of the comprehensibility ratings task (the controlgroup) was to equate the three groups in their priorexperience with the standards.Materials and procedure Participants were randomlyassigned to the three conditions. In the first part of thecommonality-listing (or difference-listing) condition, 18sentence pairs were presented (12 test items and 6 filleritems), and space for written responses was provided beloweach pair. Participants were instructed to compare thesentences and then to write out as many of theircommonalities (or differences) as possible. In thecomprehensibility condition, participants rated thecomprehensibility of individual sentences on a scale from 1(not at all comprehensible) to 9 (completelycomprehensible). In all, 45 sentences were presented: 36from the 18 pairs of test items and fillers, plus 9 lowcomprehensibility fillers specific to the first part of thiscondition that were designed to anchor the ratings scale.The second phase was identical for all three groups. Allparticipants received 18 triads (12 test item triads and 6filler triads) in random order. Each triad consisted of a pairof sentences serving as standards (those presented in thefirst part of the commonalities and differences conditions,with both the order between and within pairs rerandomized); and the two response options, one an attributematch with the standards, and the other a relational matchwith the standards. The subject, object, and verb for thestandards were chosen so that the action described in thesentences would be familiar to participants. Thesuperficially similar option had the same subject as thestandards, but was otherwise semantically unrelated. Therelationally similar option conveyed an event that wassimilar to those in the standards, but had no object match. Itwas constructed with the intent of establishing a matchingpredicate argument structure with the standards. A sampletriad is presented in Figure 2.The plumber tested the new faucet.The plumber inspected the pipes.The plumber mailed thecustomer the bill.The accountantchecked the totals.Figure 2. Sample test stimulus used in the experiment.The filler triads were designed so that the correct responseoption shared both object and relational matches with thestandard(s). The fillers were included in order to circumventformulaic responding. The order of items and left-rightplacement of response options was randomized.Even though the second task is a comparison task for allconditions, our prediction is that the more intensive priorcomparison tasks of listing commonalities or listingdifferences should affect the rate of relationalresponding accordingly. The tasks were self-paced, andtook about 15-20 minutes to complete.ResultsAs predicted, participants who listed commonalitiesresponded relationally more often (M .84, SD .14)than those who rated the comprehensibility ofindividual sentences (M .65, SD .15), tI(11) 7.32,p .001, by a paired-samples t-test over items. Further,those who listed differences also responded relationallymore often than those who rated single-sentencecomprehensibility, tI(11) 1.74, p .05. An ANOVAconfirmed an overall between-subjects effect, F(2, 76) 3.08, p .05. A marginally significant trendsuggested that people who listed commonalitiesresponded relationally more often than those who listeddifferences (M .76, SD .15), tI(11) 1.30, p .10.Thus, the chief prediction was borne out: listingcommonalities led to a gain in relational focus. Inaddition, the difference-listing group also showed again in relational focus, allowing us to discount theexplanation that listed relational commonalities weresimply carried over from the first part of the task.General DiscussionWe tested the prediction that comparison would lead tothe highlighting of common relational structure evenfor literally similar pairs. Two different comparisontasks were used: a commonality-listing task and adifference-listing task. In both cases, the prediction thatstructural alignment would lead to a focus on commonrelational structure was supported.The finding that difference listing as well ascommonality listing led to heightened relationalresponding supports Markman and Gentner’s (1996)claim that finding differences typically invitesstructural alignment just as does finding commonalities.Not surprisingly, the relational highlighting effectappears weaker for difference listing than forcommonality listing.The results of the study buttress the claim thatcomparison leads to the noticing of common relationalstructure. However, there are still issues to explore.Structure-mapping predicts that the differencesadvantage should happen primarily in the case ofalignable differences (which is the result of a sharedproperty between objects, but with each objectpossessing different values for that property). However,the way in which the stimuli in the experiment werestructured doesn’t provide evidence that alignabledifferences were responsible for the heightenedrelational focus. For example, for one item in thedifference-listing task, a participant wrote, “Bothcoaches, but one is for the Bears and the other is for theRaiders”, whereas another participant wrote,“Bears/Raiders”. Now, it appears that these are bothalignable differences, but it is not entirely clear that the

participants thought of them as such. It may have been thecase that the second participant engaged in a rather shallowlevel of processing, perhaps only noting that words in thesame relative location within each sentence happened to bedifferent. It seems, then, that the written responses do notprovide very many clues as to the types of differencesinvolved in the task. However, sentence stimuli that are notmatched completely may get around this limitation.ConclusionsThe current results add to the set of findings suggesting thatsimilarity is most tractable when viewed, not as an endproduct or as a static mental rating, but rather as a processoperating over mental representations (Medin, Goldstone,& Gentner, 1993). Furthermore, these findings suggest thatsimilarity comparison processes may have importantpsychological consequences – notably, leading to a focus onrelational commonalities (Gentner & Medina, 1998; Gentner& Namy, 1999). Spontaneous comparison processes may beone route by which children can use experiential learning tobootstrap their way to abstract rule-like knowledge. Clearly,this ability to sharpen our grasp of relational similarity iscrucial: it is what enables the Newton or the Einstein to notethe spectacular in the mundane.AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by ONR award N00014-02-10078. Thanks to Sam Day and the rest of the Similarityand Analogy group.ReferencesAhn, W. (1999). Effect of Causal Structure on CategoryConstruction. Memory & Cognition, 27, 1008-1023.Boroditsky, L. (in press). Comparison and the developmentof knowledge. Cognition.DeLoache, J. S. (1987). Rapid changes in the symbolicfunctioning of very young children. Science, 238, 1556557.Falkenhainer, B., Forbus, K. D., & Gentner, D. (1989). Thestructure-mapping engine: Algorithm and examples.Artificial Intelligence, 41, 1-63.Gentner, D. (1983). Structure-mapping: A theoreticalframework for analogy. Cognitive Science, 7, 155-170.Gentner, D. (2003). Why we’re so smart. In D. Gentner andS. Goldin-Meadow (Eds.), Language in mind: Advancesin the study of language and cognition (pp. 195-236).Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Gentner, D., & Gunn, V. (2001). Structural alignmentfacilitates the noticing of differences. Memory andCognition, 29(4), 565-577.Gentner, D., & Markman, A. B. (1994). Structuralalignment in comparison: No difference withoutsimilarity. Psychological Science, 5(3), 152-158.Gentner, D., & Markman, A. B. (1997). Structure mappingin analogy and similarity. American Psychologist, 52, 4556.Gentner, D., & Medina, J. (1998). Similarity and thedevelopment of rules. Cognition, 65, 263-297.Gentner, D., & Namy, L. (1999). Comparison in thedevelopment of categories. Cognitive Development,14, 487-513.Gentner, D., & Toupin, C. (1986). Systematicity andsurface similarity in the development of analogy.Cognitive Science, 10, 277-300.Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1983). Schemainduction and analogical transfer. CognitivePsychology, 15, 1-38.Holyoak, K. J., & Thagard, P. (1989). Analogicalmapping by constraint satisfaction. CognitiveScience, 13, 295-355.Imai, M., Gentner, D., & Uchida, N. (1994). Children'stheories of word meaning: The role of ment, 9, 45-75.Kurtz, K. J., & Gentner, D. (2001). Kinds of kinds:Sources of category coherence. Proceedings of theTwenty-third Annual Conference of the CognitiveScience Society, 522-527. Mahwah, NJ: LawrenceErlbaum Associates.Kurtz, K. J., Miao, C., & Gentner, D. (2001). Learningby analogical bootstrapping. Journal of the LearningSciences, 10(4), 417-446.Loewenstein, J., & Gentner, D. (2001). Spatial mappingin preschoolers: Close comparisons facilitate farmappings. Journal of Cognition and Development,2(2), 189-219.Loewenstein, J., Thompson, L., & Gentner, D. (1999).Analogical encoding facilitates knowledge transfer innegotiation. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 6(4),586-597.Markman, A. B., & Gentner, D. (1993a). Splitting thedifferences: A structural alignment view ofsimilarity. Journal of Memory and Language, 32,517-535.Markman, A. B., & Gentner, D. (1993b). Structuralalignment during similarity comparisons. CognitivePsychology, 25, 431-467.Markman, A. B., & Gentner, D. (1996). Commonalitiesand differences in similarity comparisons. Memory &Cognition, 24(2), 235-249.Medin, D. L., Goldstone, R. L., & Gentner, D. (1993).Respects for similarity. Psychological Review,100(2), 254-278.Shepard, R. N. (1962). The analysis of proximities:Multidimensional scaling with an unknown distancefunction. Part 1. Psychometrika, 27, 125-140.Smith, L. B., Jones, S. S., & Landau, B. (1992). Countnouns, adjectives, and perceptual properties inchildren's novel word interpretations. DevelopmentalPsychology, 28, 273-286.Tversky, A. (1977). Features of similarity.Psychological Review, 84, 327-352.

Figure 1. Sample stimuli used in a cross-mapping task (from Markman & Gentner, 1993b, study 1). In structure-mapping, because predicates that belong to connected systems are weighted more heavily than isolated predicates, the theory predicts that relational matches will in general outweigh object matches. Prior