Transcription

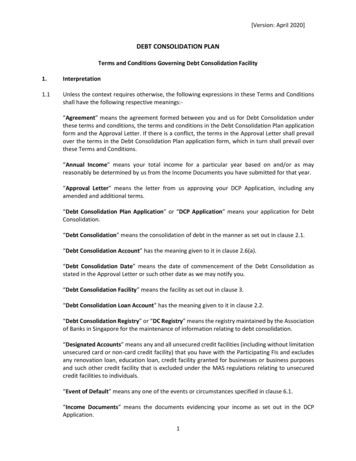

No. 11-04July-August 2011Public Debt and Fiscal ConsolidationBy Roy R. Hernandez1IntroductionA Closer Look at Public Debtshe recent global financial crisisnecessitatedthepromptandcoordinated actions of monetary andfiscal institutions across countries to preventthe global economy from plunging into a widescale depression. Loose monetary policybecame necessary to encourage economicactivities. This was complemented byaccommodative fiscal policies, implementedthrough various fiscal stimulus measures, tooffset the slack in private sector demand. Thecrisis has reduced productive capacity andtherefore tax revenues, and at the same timehas caused government spending (and, as aconsequence, government borrowings) to riseto record levels following the implementationof fiscal stimulus measures. This has raisedconcerns about the debt sustainability ofcountries, particularly those mired in soaringsovereignborrowings.Hence,severalEurozone governments, starting with Greece,experienced funding turmoil when investorsdoubted its repayment capability anddemanded higher returns for lending money.The turmoil spread over to other members ofthe Eurozone such as in Ireland and Portugal.The European sovereign debt problemprompted the provision of official financialassistance to the affected countries from theIMF, European Commission and Europeancentral banks.How are Public Debts IncurredMeanwhile, emerging market economies(EMEs) recovered faster from the globalfinancial crisis relative to developed countries,which enabled them to start the normalizationprocess early. Liquidity-enhancing measuresimplemented during the crisis were unwoundand policy rates were adjusted gradually insome EMEs to counter emerging inflationarypressures.The public sector issues several types ofdebts as follows:Tublic debts are incurred to finance theactivities of the public sector eitherthrough the revenue streams generatedfrom taxation, or through borrowing in thefinancial market. In the latter this could bethrough term loan facilities whereby a publicinstitution borrows from financial institutionsdirectly. The government could also borrowdirectly from the private sector through itsregular auctions of government securities, orthrough issuance of other sovereign debtpapers.PPublic debts could be affected by economicvariables. For example, inflation could reducethe value of debts as the government willhave to repay the borrowed amount ratherinexpensively when inflation increases, allelse remaining equal. Likewise, monetarypolicy has a vital impact on public debtsthrough the interest rate channel. Whencentral banks decide to raise interest rates,the cost of debt offering will correspondinglyincrease. Expectations about interest ratesalso affect market valuation of existing publicdebts that, like other financial assets, arebought and sold in the financial market.Classification of Public Debts1. Type of public sector debt issuances. Thenational government (NG) issues debts tofinance a portion of its operations, apartfrom revenues raised from tax collection.Local government units also have thepower to borrow, as well as governmentowned-and-controlled corporations andgovernment financial institutions. The NGmay opt to explicitly guarantee their1Bank Officer V, Department of Economic Research1

July-August 2011borrowings. Taken together, public sectordebts are accounted in the consolidatedpublic sector fiscal position (CPSFP),which refers to the net deficit or surpluscalculated after summing-up the budgetbalances of all government entities.2undertaking are used to spur economicdevelopment. One of the reasons for theexistence of government is to provide publicgoods and services that offer little profitincentives but have significant social returns.The government will rely on its revenues –which are principally derived through taxation– to fund these socially responsive activities.The government’s revenue streams fromtaxation and its activities may not coincide,and this mismatch may be financed byborrowing first in the financial market and thenpaying when the tax revenues collected areenough to cover the debts.2. Maturity structure. Public sector entitiescould decide to borrow either short- orlong-term, consistent with their borrowingguidelines and debt management thrust.The NG typically conducts its short-termborrowings through the issuance ofTreasury bills (T-bills) that carry maturitiesof three months to one year. Long-termborrowings are financed by issuing longerdated Treasury bonds, foreign-currencysovereign debt issuances and such otherdebentures.Aside from the apparent time mismatchbetweengovernmentrevenuesandexpenditures, the government may likewiseresort to borrowing to finance relativelyexpensive but socially responsive programswhich are essential to enhance the productivecapacity of the country. For example, thegovernment may opt to finance infrastructureprojects such as the construction of farm-tomarket roads to assist the farmers inefficiently transporting their products to theirintended destination. Alternatively, it couldembark on constructing public schools andhealth centers that could lift the human capitalresources of the country.3. Currency composition. Public sector debtscan be contracted in local currency or inforeign currencies (which are collectivelyknown as ROPs in market parlance).4. Securitized public sector debts. The publicsector may also securitize its future mple,thegovernment may issue “revenue bonds,”which will be financed by revenuescollected from specific user fees, such ashighway tolls.3The government also borrows to spureconomic activities, particularly when theprivate sector activities are constrained byweak economic conditions. For example, theexternal shocks emanating from the recentglobal financial crisis necessitated thegovernment to implement stimulus measuresto counteract the slack in private sectoractivities.Rationale of Public BorrowingsA successful fiscal adjustment is usuallydefined as the ability of a fiscal policytightening today to achieve a lasting publicdebt reduction in the future.4 Public debtarises when the expenditures of the publicsector exceeds the revenues it generates.Public debt, per se, is not undesirable so longas the proceeds generated from thisThere are instances that the governmentborrows not because it needs financing but toset benchmarks for borrowings undertaken bythe private sector. In this case, thegovernment’s objective is more of local capitalmarket deepening rather than financial affairs.2Government entities include the national government, thenon-financial government corporations (usually includes onlythe 14 major GOCCs), government financial institutions, localgovernment units, the social security institutions, the Oil PriceStabilization Fund, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, and theCentral Bank-Board of Liquidators.3Seater, John J., “Government Debts and Deficits, “ Toglhofer and Zagler, “The Impact of Different Fiscal PolicyRegimes on Public Debt Dynamics,” 2008Borrowings by the public sector shouldlikewise be managed by taking intoconsideration the overall fiscal position andthrust of the government. In instances whenthe proceeds from government borrowings arespent recklessly, government debts cease tocontribute to economic development. In2

July-August 2011addition, excessive debts could fracture themacroeconomy. They could fan inflationarypressures (through higher governmentspending), leading to rising interest rates andlower investment, as investors will loseconfidence in the government’s ability tofinance its borrowing spree. In this case,public debts become anti-developmental.decreasing taxes in periods of softeconomic activity could encouragespending and heighten economic activity,which could improve the fiscal positionand reduce the need for future borrowingsto offset the tax cuts.3. Public debts could pump-prime theeconomy without crowding-out the privatesector. During periods of weakereconomicactivityanduncertainconditions, the private sector may chooseto remain in the sidelines. Thegovernment’s task, therefore, is tostimulate aggregate demand by spurringeconomic activity.Public Debts and the Macroeconomyconomists’ views are divided on theimpact of public debts on themacroeconomy. Proponents of theRicardian equivalence argues thatincreased government borrowing may haveno impact on consumer spending becauseconsumers, by being rational, will expect taxcuts or higher spending that will lead to futuretax increases to pay back the resultingincrease in debts.5 For example, in the firstyear, an economy chose to finance itsexpenditures of, say, P100 billion (assumedconstant) through taxation. However, in thesecond year, it opted to finance theP100 billion expenditure by reducing taxationto P90 billion and issuing a P10 billion oneyear T-bills (to compensate for the reducedtaxation). The Ricardian equivalence positsthat consumers will be indifferent to a tax cutas this will be temporary and will be offset byhigher taxes to counter the increasedexpenditure requirements resulting fromT-bills maturing in one year.E4. Pump priming activity could generatemultiplier effect. The increase in outputassociated with pump-priming activity ofthe government could be higher relative togovernment spending.Public Debt SustainabilityPublic borrowings – like any other debt – carrycosts, particularly the interest expense of thefunds borrowed. The debt servicing burden –i.e., principal plus interest, which are spreadthroughout the life of the debt – couldcomprise a significant chunk of the annualgovernment budget. Debt managementshould, therefore, ensure that public debtprograms are not bunched-up (by spreadingthe maturity profile to avoid illiquidity) norexcessive (by possibly setting a debt ceiling toavoid insolvency). When countries are unableto service their debt obligations, a credit eventor default occurs. Countries rarely default ondomestic currency debt since they have theoption of printing more money.However, there are arguments against theRicardian equivalence as follows:1. Consumers may not be as rational asinitially thought. Some consumers may notanticipate that tax cuts will lead to taxhikes in the future. Thus, tax rebates areusually included in fiscal stimuluspackages during an economic downturn.Countries facing a liquidity shortage may needassistance from multilateral institutions tocounter the temporary liquidity squeeze.Meanwhile, highly indebted countries mayneed to implement strong, credible, andarguably unpopular fiscal consolidation.2. Tax cuts can boost growth and diminishborrowing requirements. Tax revenues fallin periods of slower economic growth,while government spending may increasethrough providing heightened socialservices such as higher spending onunemployment benefits. Some argue thatMultilateral institutions, such as the IMF, aswell as credit rating agencies and privatesector institutions, do regard the fiscal sector,in general, and public debt conditions, inparticular, as important indicators in gaugingthe country’s economic and political situation.5Economics.Help,“Ricardian conomics/ricardian-equivalence/3

July-August 2011Metrics are often employed to determine thecountry’s debt sustainability in terms of itsliquidity and solvency positions with respect toits public sector debt accumulation.For advanced economies where monetaryauthorities embarked on massive bond buyingprograms to help prop up the domesticeconomy, the management of sovereigndebts could affect monetary and financialstability. They could also undermine a centralbank’s credibility as large-scale buyingactivities of government bonds could beperceived as providing support for thegovernment’s financing needs, which couldgive rise to the risk of perceived threat to itsindependence.Foncerrada (2005) reiterated the IMF andWorld Bank’s stance that debt sustainabilityshould be assessed on the basis of indicatorsof the debt stock or debt service relative tovarious measures of repayment capacity.6The most commonly used is public debt-toGDP ratio to measure the financial leverage ofan economy. Other indicators include ratios offoreign debt-to-exports or internationalreserves, public debt to revenue and revenueto GDP.Fiscal ConsolidationFiscal Consolidation in Advanced EconomiesDebt sustainability is a major issue,particularly for countries facing higher publicdebts, such as what most advancedeconomies are currently experiencing. Thesecountries are vulnerable to rollover risks asmaturing debt obligations could become moreexpensive to refinance considering thatinvestors will demand significant premium tocompensate for the greater risks that they willbe assuming. The punitive action of themarket through higher borrowing costs willmake it more difficult for these countries toservice their obligations, creating a viciouscycle of debt trap. This could be aggravatedwhen governments planning to undertakeunpopular measures that will increaserevenues and/or reduce public expendituresface political backlash that render them notpolitically feasible.lberto Alesina and Roberto Perotti(1995) find that, among other things,consolidationpoliciesaremostsuccessful when they entail a reduction ofgovernment expenditures.8 There are twopossible reasons for this. First, spendingbased consolidations are usually morepersistent, as they are often combined withstructural reforms. Second, spending cutstend to be less damaging for growth than taxincreases mainly because spending-basedadjustments are typically accompanied bymonetary easing while tax-based ones oftensee monetary tightening. Goldman Sachs(2011) further argued that in the US, with theFed funds rate close to zero, both spendingand tax-based consolidations are likely tohinder economic growth. Nonetheless,spending-based adjustments might still bepreferable, particularly if properly enforced.Thus, the best that the US Federal ReserveBank can do is to keep monetary policy onhold to cushion the growth drag from fiscalconsolidation—independently of whether itcomes through adjustments in spending,revenue-generation or both.9 It may be notedthat the US needs a very large fiscalconsolidation, with Goldman Sachs projectinga primary (ex-interest) deficit of 7.7 percent ofGDP for 2011. Failure by US policy makers toreach consensus on medium-term fiscalconsolidation might lead to a disorderly USDdecline and loss of confidence amongst68Another set of indicators focuses on thecountry’s ability to service its short-termobligations, and are used to gauge thecountry’s liquidity conditions. These includeratios such as debt service to GDP, foreigndebt service to exports and government debtservice to current fiscal revenue. Otherindicators are also being used to determinehow the debt burden ratios would change inthe absence of repayments or newdisbursements (e.g., by getting the averageinterest rate on outstanding debt scaled to thegrowth rate of nominal GDP).7AFoncerrada, Luis, “Public debt sustainability. Notes on debtsustainability, development of a domestic governmentsecurities market and financial risks,” 20057Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/External debtToglhofer and Zagler, “The Impact of Different Fiscal PolicyRegimes on Public Debt Dynamics,” 20089Goldman Sachs, “Fiscal Adjustment without Fed Easing: ATall Order,” 14 May 20114

July-August 2011holders of US Treasuries.10 Thus, on 5 August2011, Standard and Poor’s decided to cut thelong-term sovereign rating of the US to AA (with negative outlook), the first time a creditrating agency has done so.the EFSF has been amended twice to extendits scope and expand its size. While theamendments have been agreed, they remainto be ratified by the national procedures of theeuro area member states.13 However, thesereform measures, together with the stricterenforcement of the debt rules, could reducesolvency risk but will not eliminate it.14The Eurozone faces a similar pressing needfor fiscal consolidation, given the lingeringEuropean sovereign debt turmoil. Some havespeculated that it is just a matter of timebefore Greece will default on its existingobligations. Sovereign debt woes have spilledover across Eurozone countries, threateningto engulf bigger countries like Spain and Italy.This prompted the European Central Bank toreverse the sell-off of Spanish and Italianbonds.The Eurozone episode highlights notonly the dark side of borrowing beyond one’smeans but also the limited policy toolkit ofcountries toaddress elevated fiscalimbalances under a unified monetary system.Given these concerns, the European Unionsummit recently agreed to strengthen furtherthe fiscal framework for the Eurozone. Theamendments to the existing rules andregulations focused on: (1) economicgovernance, which is meant to prevent anycountry ever again from coming close to afiscally unsustainable position; and (2) newcrisis mechanism, which comes into play oncea country faces imminent funding problems.11While these initiatives aim to enforce closerfiscal policy coordination, they do not fullyaddress the issue of solvency that has arisenas a consequence of the debt crisis. TheEuropean Financial Stabilization Facility(EFSF), established in May 2010 withguarantee commitments of EUR440 billionaims to preserve the financial stability ofEurope’s monetary union by providingtemporary financial assistance to euro areamember states in difficulty.12 It became fullyoperational on 4 August 2010 and to date hasissued three bonds to fund loans to Irelandand Portugal. Since it was originally set up,These fiscal policy constraints amongadvanced economies have become a majorconcern among investors. Implementing fiscalconsolidation could lead to negative shocksthat could shake, if not wipe out, the modesteconomic gains achieved so far. PacificInvestment Management Co. (PIMCO) arguedthat sovereign creditworthiness will continueto diverge, with the deterioration in advancedcountries contrasting with the continuedimprovement in the emerging world. Thisscenario could foster heightened financialrepression and higher inflation.15Fiscal Consolidation in EMEsEMEs have emerged from the recent globalfinancial crisis relatively less scathed thanadvanced economies. In fact, bright economicgrowth prospects and favorable interest ratedifferentials have encouraged heightenedcapital inflows. These, together with risinginternational commodity and food prices, haveraised concerns about the buildup ofinflationary pressures, which could lead to atighter fiscal policy stance.Fiscal Consolidation in the PhilippinesIn the Philippines, the current administrationhas made fiscal sustainability the cornerstoneof its governance agenda. Efforts are beingundertaken by the government to improve taxcollection. It may be noted that the nationalgovernment’s (NG) revenue collection scaledto GDP has been stable, rising by14.2 percent in 2010, which is slightly lowerthan the previous year’s 14.6 percent growth.The tax effort (tax collection to GDP ratio) wasunchanged at 12.8 percent in 2010 and 2009,but comparably lower than the ratio in 2008 of14.2 percent. It is in this light that the10HSBC, “Asia’s Bond Market,” May 2011Goldman Sachs, “A More Stable Eurozone after theComprehensive Package,” 8 April 201112A new permanent crisis mechanism, the European StabilityMechanism (ESM), will be set up in the euro area as of mid2013 following the expiry of the existing EFSF. The ESM willcomplement the new framework for reinforced economicsurveillance in the EU. This new framework, which includes inparticular a stronger focus on debt sustainability and moreeffective enforcement measures, focuses on prevention and willsubstantially reduce the probability of a crisis emerging in thefuture.11131415Credit Suisse, EFSF (R)evoltion, 16 August 2011HSBC, European Economics Quarterly, 29 March -OutlookNavigating-the-Multi-Speed-World.aspx5

July-August 2011government has implemented measures toimprove the government’s tax collection suchas the Run Against the Tax Evaders (RATE),Run After the Smugglers (RATS) andRevenue Integrity Protection Service (RIPS).Moreover, measures to rationalize thegovernment’s fiscal incentive programs areunderway to minimize their negative impacton the government’s revenues.June 2019, September 2024, October 2024,2025, 2030, and 2031 the chance to replacetheir holdings with a fresh tranche of bondsdue 2034. For domestic borrowings, the NGhas been periodically launching bondexchange programs over the years. InDecember 2010, the Bureau of the Treasuryswapped around P200 billion of existingbonds for new 10- and 25-year bonds.In addition, the government has embarked ona pro-active debt management strategy whichaims to reduce the debt stock and debtservice payments and lengthen the maturityprofile where feasible through debt swaps andexchanges. Debts with longer duration enablethe government to finance urgent programsnecessary for economic development suchthat when these debts mature, the countrycould easily repay them on the back of theeconomy’s improved capacity.On the expenditure side, disciplined use ofpublic resources resulted in a governmentexpenditure-to-GDP ratio of 7.1 percent in2010 from double-digit rates recorded in theprevious three years. The governmentexpressed its commitment to efficient fiscalexpenditure program through the followingreforms:16 Zero-based budgeting: across-the-boardreview of all budgets to cut waste; Focused targeting of social programsensuring that funds are channeledappropriately; Advancing the Pay-Go legislation: A lawthat requires all new expenditure andrevenue-eroding legislation to be matchedwith revenue-increasing measures; and Tighter implementation of procurementlaws that will allow greater scrutiny of allpublic procurement to cut waste.The stock of NG’s total outstanding debt as apercent of GDP has been on a decliningtrend. The ratio was 55.4 percent in 2010compared to previous year’s 57.3 percent. InApril 2011, the NG debt-to-GDP ratio declinedfurther to 51.2 percent against last year’s53.9 percent. The NG targets a debt-to-GDPratio of 55 percent for this year. The share offoreign-currency denominated obligations hasshrunk to 43.8 percent in 2010 against50.7 percent share in 2010. This was a resultof the NG’s thrust to borrow in domesticcurrency to mitigate foreign exchange riskinherentininternationalborrowingtransactions. For example, following thesuccessful launch of the first-ever global pesobonds last September 2010 that raisedUS 1 billion, the NG issued anewUS 1.25 billion of global peso bonds inJanuary 2011.Concluding Remarksotwithstandingthevariedfiscalconditions across countries, it isparamount that fiscal policy remainsrelevant and supportive of long-termeconomic progress. This can be achievedthrough the efficient management of publicsector debts to minimize the medium- andlong-term expected costs of funding thegovernment’s activities. The dynamics inincurring public debt should include a debtmanagement strategy that will take intoaccount not only the reasons for borrowingbut likewise the sustainability of incurringdebts. Finer details inherent in debttransactions should be addressed, includingissues about diversifying potential creditors,NIn an effort to lengthen the government’sexternal debt maturity profile, the governmenthas instituted bond exchange transactions forboth its domestic and foreign debt securities.In September 2010, it entered into aUS 3-billion debt exchange, which involvedthe issuance of dollar-denominated globalbonds due 2021 or an additional tranche ofbonds due 2034 in exchange for existingbonds due 2011, 2013, 2014, 2015, January2016, October 2016, and 2017. It also offeredholders of bonds due January 2019,16Philippine Economic Briefing, “Daylight in the Philippines:Accelerating Progress,” 23 March 20116

July-August 2011currencies, debt instruments and duration.Accountability and transparency of edia, sCredit Suisse, EFSF (R)evolution, 16 August 2011Department ofBudget and Management,http://www.dbm.gov.ph/index.php?pid equivalence/Foncerrada, Luis, “Public debt sustainability. Noteson debt sustainability, development of adomestic government securities market andfinancial risks,” 2005Goldman Sachs, “A More Stable Eurozone after theComprehensive Package,” 8 April 2011Goldman Sachs, “Fiscal Adjustment without FedEasing: A Tall Order,” 14 May 2011Goldman Sachs, “Implications of S&P’s NegativeOutlook on US Sovereign Debt,” 18 April 2011HSBC, “Asia’s Bond Market,” May 2011HSBC, European Economics Quarterly, 29 March2011Pacific Investment Management Company the-Multi-SpeedWorld.aspxPhilippine Economic Briefing, “Daylight in thePhilippines: Accelerating Progress,” 23 March2011Seater, John J., “Government Debts and Deficits,“The Concise Encyclopedia of nmentDebtandDeficits.htmlToglhofer and Zagler, “The Impact of DifferentFiscal Policy Regimes on Public DebtDynamics,” 20087Department of Economic ResearchMonetary Stability SectorDisclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are thoseof the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of theBangko Sentral ng Pilipinas management. Articles may bereproduced, in whole or in part, provided properacknowledgement of source is made. Please send comments,feedbacks and/or inquiries to: The BSP Economic NewsletterEditorial Staff, Room 401, 4/F, Five-Storey Bldg., BangkoSentral ng Pilipinas, A. Mabini St., Malate, Manila 1004;telephone no. (632) 523-1190; fax no. (632) 523-1840. E-mail:bspmail@bsp.gov.ph.

Public borrowings - like any other debt - carry costs, particularly the interest expense of the funds borrowed. The debt servicing burden - i.e., principal plus interest, which are spread throughout the life of the debt - could comprise a significant chunk of the annual government budget. Debt management