Transcription

Myanmar’s Education Reforms

Myanmar’s EducationReformsA pathway to social justice?Marie Lall

First published in 2020 byUCL PressUniversity College LondonGower StreetLondon WC1E 6BTAvailable to download free: www.uclpress.co.ukText Author, 2021Images Author and copyright holders named in captions, 2021Marie Lall has asserted her rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988to be identified as the author of this work.A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library.This book is published under a Creative Commons 4.0 International licence (CCBY 4.0). This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; toadapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is madeto the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use ofthe work). Attribution should include the following information:Lall, M. 2020. Myanmar’s Education Reforms: A pathway to social justice? London: UCLPress. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787353695Further details about Creative Commons licences are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commonslicence unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. If you would like tore-use any third-party material not covered by the book’s Creative Commons licence,you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.ISBN: 978-1-78735-404-3 (Hbk.)ISBN: 978-1-78735-387-9 (Pbk.)ISBN: 978-1-78735-369-5 (PDF)ISBN: 978-1-78735-410-4 (epub)ISBN: 978-1-78735-416-6 (mobi)DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787353695

For those who were part of this 16-year research journey: the Egresssisterhood – Nan Theingi, Khin Moe Samm, Thei Su San, Phyo Thandar andmy Myanmar family – Aung Htun, Nwe Nwe San and their daughter Mia.Figure 0.1 Khin Moe Samm, Phyo Thandar, Nan Theingi and Nwe NweSan at Thei Su San’s wedding, Yangon, 2015. Source: Author.

ContentsList of figures and tables List of abbreviations Acknowledgements Introduction ixxixix11The state of education, pre-reform 302Education reform and effects on basic education 583The alternative: Monastic education 1014Higher education: Towards international standardsin a neo-liberal world 130Teacher education and training: Is changingpractice possible? 1596Ethnic education: Language and local curriculum issues 1977Ethnic education: Recognising alternative systemsrun by ethnic armed organisations 238Conclusion: Whither social justice in Myanmar? 2735References Index 286297Contentsvii

List of figures and .36.16.26.36.46.5Khin Moe Samm, Phyo Thandar, Nan Theingi andNwe Nwe San at Thei Su San’s wedding, Yangon, 2015 Map of Myanmar Rural government school, 2014 Education protests, 2015 Leadership and management seminars for informeddecision making for the Ministry of Education, 2019 Monastic school, 2010 Monastic teacher training: Network of CCAtrainers, 2010 Phaung Daw Oo Monastic School, 2010 teachers’focus group discussion Monastic school parents Yangon Region, 2010 parents’focus group discussion Monastic school in Mandalay, 2010 Transforming Higher Education Programme, seniormanagement from 11 Universities, 2018 First National Higher Education Conference with Ministerof Education, 2018 Second National Higher Education Conference, 2018:Building Quality and Equity in Higher Education Ethnic education representatives meet ComprehensiveEducation Sector Review (CESR) team, 2013 Conversation with the Akha community, 2018 Members of the Dainet community, 2018 Members of the PNO, PDN, PWEF and PLCO with DawAye Aye Tun, 2016 Shan State Pa-O Teacher Education College, 2018 t of figures and tablesix

7.17.27.37.47.57.6Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) ceremony 2015with General Min Aung Hlaing on the screen as heprepares to sign Mon National School, 2013 Shan language books developed by the Shan Literatureand Culture Associations (LCA) Kaw Dai, Shan State, 2018 Kachin State non-government teacher workshop, 2015 Joint MNEC and Mon SEO workshop 2018, led by VirenLall with Mi Kun Chan Non translating 245248253257263265Tables6.16.26.36.46.57.1xAdult literacy rates by sex, urban and rural areas,states/regions, 2014 Census School attendance rates by age, sex, states/regions,2014 Census Proportion of population aged 25 and over with noschooling by sex, urban and rural areas, states/regions, 2014 Census Children aged 7–15 by school attendance, states/regions, 2014 Census Percentage of population aged 25 and over by highestcompleted level of education by sex, states/regions,2014 Census Typology of ethnic schools MYANMAR’S EDUCATION REFORMS212213214215217242

List of CCRPCDFCDTCESRCLCCPDCPMEASEAN–Australia/New Zealand Free Trade AreaAll Burma Federation of Students’ UnionsAction Committee for Democratic EducationAsian Development BankAdventist Development and Relief AgencyArakan National PartyAsia Peace and Education FoundationAnnual Progress Review(s)ASEAN Qualifications Reference FrameworkAssociation of Southeast Asian NationsAthletic, Stationary and LibraryAssistant Township Education Officers AUN – ASEANUniversity NetworkASEAN University Network Quality Assurance FrameworkASEAN University Network(now Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade – DFAT)Academic YearBritish CouncilBurmese Communist PartyBorder Guard Force,Burnet Institute MyanmarBurma UK Partnership for EducationCommunity Based OrganisationChild-Centred Approaches (in Education)COVID-19 Comprehensive Relief PlanCapacity Development FundCurriculum Development TeamComprehensive Education Sector ReviewCommunity Learning CentreContinuous Professional DevelopmentCentre for the Promotion of Monastic EducationList of abbreviationsxi

FGDGDPGEIxiiCurriculum Reform at Primary Level of Basic EducationCentre for Rural Education and DevelopmentCivil Society OrganisationsConfederation of Trade Unions – MyanmarDanish International Development AgencyDaw Aung San Suu KyiDanish International Development AgencyDepartment of Basic EducationDeputy Director GeneralsDistrict Education Office/r(s)Department of Educational Planning and TrainingDepartment of Education Research, Planning and TrainingDepartment of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia)Department for International Development (UK)Director GeneralDepartment of Higher EducationDemocratic Karen Benevolent/Buddhist ArmyDepartment of Myanmar Education ResearchDevelopment Partner Coordination GroupDiploma in Teacher EducationDepartment of Teacher Education and TrainingDaily Wage TeachersEthnic Armed GroupsEthnic Armed OrganisationsEthnic Basic Education ProvidersEarly Childhood Care and DevelopmentEarly Childhood Centres for EducationEducation Directory and Guide for EveryoneEducation for AllEnglish for Education College TrainersEducation Management Information System(s)Education Promotion Implementation CommitteeEnglish Skills for EveryoneEducation Sector Coordination CommitteeEducation Sector Reform ContractEducation Technical Working GroupEquipping Youth for Employment ProjectFramework for Social and Economic ReformsFocus Group DiscussionGross Domestic ProductGender Inequality IndexMYANMAR’S EDUCATION REFORMS

DAKECKEDKESAGKGKHRGKIAKIOKIO-EDKnEDNKNPPGross Enrolment Ratio(s)Gender Equality and Social InclusionGesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GermanCorporation for International Cooperation)Global Partnership for EducationHuman Development IndexHigher EducationHigher Education InstitutionHigher Education SubsectorHuman Resource DevelopmentInternational Bureau of EducationInternational Court of JusticeInformation and Communication TechnologyInternally Displaced person/ peopleIncome Generating ActivitiesIntegrated Household Living Conditions AssessmentIntegrated Household Living Conditions SurveyInstitute of Liberal Arts and SciencesInternational Language and Business CentreInternational Labour OrganisationInternational Monetary FundInternational Non-governmental OrganisationIn-service and teacher educationInstitute(s) of EducationIrrawaddy Policy ExchangeInformation TechnologyJunior Assistant TeachersJoint Education Sector Working GroupJapan International Cooperation AgencyKonrad Adenauer StiftungKachin Defense ArmyKachin Education ConsortiumKaren Education DepartmentKaren State Education Assistance GroupKindergartenKaren Human Rights GroupKachin Independence ArmyKachin Independence OrganisationKachin Independence Organisation – Education DepartmentKarenni Education and Development NetworkKarenni National Progressive PartyList of abbreviationsxiii

ivKaren National UnionKaren Refugee Committee Education EntityKaren State Education Assistance GroupKaren Teacher Working GroupLocal CurriculumLiterature and Culture AssociationsLiterature and Culture CommitteesLahu Democratic UnionLanguage, Education and Social Cohesion InitiativeLanguage of InstructionMonthly CurriculumMulti-Donor Education FundMillennium Development Goal(s)Myanmar EgressMyanmar Education ConsortiumMonastic Education Development GroupMyanmar Education Partnership ProjectMyanmar Education Research BureauMonastic Education Supervisory CommitteesMyanmar Fisheries FederationMyanmar Information Management UnitMyanmar/Burma Indigenous Network for EducationMyanmar Literacy Resource CentreMyanmar Maternal and Child Welfare AssociationMon National Education CommitteeMon National SchoolsMemoranda of AgreementsMinistry of EducationMinistry of Ethnic AffairsMinistry of Foreign AffairsMinistry of Planning and FinanceMinistry for Religious AffairsMemoranda of UnderstandingMembers of ParliamentMinistry of the Progress of Border Areas and National RacesMyanmar Peace CentreMon Summer Literacy and Buddhist CultureMinistry for Social WelfareMother Tongue Based Multi-Lingual EducationMid Term ReviewMandalay University of Distance EducationMYANMAR’S EDUCATION REFORMS

MUPEMWAFNAQACNCANCCNDA-KNELNERNEPCNESPMyanmar-UK Partnership for EducationMyanmar Women’s Affairs FederationNational Accreditation and Quality Assurance CommitteeNationwide Ceasefire AgreementNational Curriculum CommitteeNew Democratic Army-KachinNational Education LawNet Enrolment RatioNational Education Policy CommissionNational Education Strategic Plan (since 2016) / NationalEducation Sector Plan (pre 2016)NGONon-Government Organisation(s)NIHEDNational Institute of Higher Education DevelopmentNLDNational League for DemocracyNMSPNew Mon State PartyNNERNational Network for Education ReformNPANational Plan for ActionNPTNay Pyi Taw (Myanmar’s capital)NUSNational University of SingaporeOCAOrganisational Constraints AnalysisOECDOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and DevelopmentOECD/DAC OECD’s Development Assistance CommitteeOHCHROffice of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHuman Rights).OOCSOut of School ChildrenOPMOxford Policy ManagementOSFOpen Society FoundationOSYOut-of-School YouthPACEPeople’s Alliance for Credible ElectionsPATPrimary Assistant TeacherPDNParami Development NetworkPEPCParliamentary Education Promotion CommitteePNLAPa-O National Liberation Army (PNLA)PNOPa-O National OrganisationPPEPost-Primary EducationPPTTPre-Primary Teacher TrainingPTAParent Teacher AssociationQBEPQuality Basic Education ProgrammeRCRectors’ CommitteeRCSSRestoration Council of Shan State (Political wing of a ShanState Army)List of abbreviationsxv

iRestoration Council of Shan State – Education DepartmentRegional Education OfficeRural Indigenous Sustainable EducationRural Shan State Development FoundationReading, Writing and Critical ThinkingSenior Assistant TeacherSelf Administered ZoneSustainable Development GoalsSecondary Education Sub-sectorState Education Office(r)Special Economic ZonesSchool Improvement FundsSchool Improvement Support ProgrammeSchool-based In-service Teacher EducationSaJaNa – Shan State Kachin Baptist UnionShan Literature and Cultural AssociationState Law and Order Restoration CouncilShan Nationalities League for DemocracyState Peace and Development CouncilShan State ArmyShan State Progressive PartyStrengthening Pre-service Teacher Education in MyanmarSagaing University of EducationTeaching Assistant(s)The Border ConsortiumTeacher Centred ApproachTeacher Competency Standards FrameworkTeacher Education TeamTownship Education Office(r)Terms of ReferenceTowards Results in Education and EnglishTeacher Training CollegesTeacher Training SchoolsTechnical and Vocational Education and TrainingUniversity for Development of National RacesUnion Election CommissionUnited Nations Development ProgrammeUnited Nations General AssemblyUnion Election CommissionUnited Nations Educational, Scientific and CulturalOrganisationMYANMAR’S EDUCATION REFORMS

UNICEFUNOCHAUSDAUSDPUSIPWBYUYUDEYUOEYWCAUnited Nations International Children’s Emergency FundUnited Nations Office for the Coordination of HumanitarianAffairsUnion Solidarity and Development AssociationUnion Solidarity and Development PartyUnited States Institute of PeaceWorld BankYangon UniversityYangon University of Distance EducationYangon University of EducationYoung Women’s Christian AssociationList of abbreviationsxvii

AcknowledgementsMuch of the research on the ground – especially before 2013 – wouldhave been impossible without the research team I was able to build atMyanmar Egress. This book is therefore dedicated to the Egress sisterhoodMoe, Phyo, TG and Thei Su as well as Aung Htun and Nwe Nwe San, whoaccompanied me on multiple trips around the country.Over the past five years, it has become somewhat easier to doresearch in Myanmar’s education institutions. In this time, I have workedwith a large number of people, but my fondest memories go to my time inthe field with Aye Aye Tun who has become a very dear friend.I have many colleagues and friends to thank in Mon, Kachin, Karenand Shan States – in particular, Mi Kun Chan Non, Mi Sardar (especiallyfor that unforgettable trip to Nyisar) in Mon State, Dr Lu Awn in KachinState and Daw Nang Wah Nu, who made it possible for me to travel acrosssouthern Shan State. Many thanks also to Kaw Dai for the warm welcomein their HQs, they do truly amazing work.In NPT, my thanks go to the many patient MoE officials who havespent numerous days with me discussing many aspects of the educationreform process. Their work is super hard and yet they are not tiring of it(and of all the foreigners who regularly come and bug them). Also thankyou to Susannah Hla Hla Soe and Ma Shwe Latt, who manage to maketime to meet in between the busy parliamentary sessions.In Yangon, my thanks go to my very old friends Tin Maung Thannand U Hla Maung Shwe, who I wish I could see more of as well as MaThanegi and of course Dr Nay Win Maung’s mother – Mummy to me – whostill feeds me on every one of my visits.This book could not have been written without the help and collaboration of all the teachers, parents, teacher educators, student teachers, TEOofficials, SEO officials, monastic heads, academic colleagues, LCA/LCCmembers, EAO representatives and Civil Society Organisation memberswho gave their time to answer questions, explain the local situation andrelate their views. I hope this book does justice to their voices.Acknowledgementsxix

In Tokyo, my thanks go to my colleagues and friends, who havespent many hours talking about the country with me. In particulardiscussions with Ikuko Okamoto, Kei Nemoto and Yukako Iikuni whohave spent years working on Myanmar were invaluable. Special thanksalso to the Myanmar JICA teams in Tokyo and Yangon who made time toexplain the various Japanese programmes. This book would not havebeen written had I not been able to access the Tokyo Metropolitan Libraryover the summer and winter 2019. This serene, quiet space in the midstof the Arisugawa-no-miya Memorial Park, far away from the London(and Yangon rush) was my sanctuary and my inspiration.Many thanks to ANU who have allowed me to reproduce one oftheir maps of Myanmar and Gerard McCarthy who helped me to get theright permission.In London, much thanks are due to my editor Pat Gordon-Smith,who turned this book around in record time.As always, my thanks and love to my husband who over the last25 years has put up with my absence, but who did join me on one of mylast Myanmar trips as a part of my team.Marie LallLondon, during the COVID-19 lockdown, June 2020xxMYANMAR’S EDUCATION REFORMS

IntroductionA policy window for changeThe landslide election victory of the National League for Democracy(NLD) in 2015 offered a window for change – a so called ‘policy window’(Marshall, 2000) – to lead Myanmar’s reform process according to theoriginal NLD values that included a left-leaning view of social justice andthe empowerment of the poorest and most disadvantaged communitiesas a part of the political and economic transformation of Myanmar.1This book, written from mid-2019 to mid-2020, is a snapshot takentowards the end of the first five years of NLD rule, evaluating the progressmade, nevertheless casting an eye on the future of Myanmar beyond the2020 elections.The reality on the ground after almost ten years of reforms – fiveyears under President Thein Sein and almost five years under DawAung San Suu Kyi – does not point to a social justice agenda. The mostmarginalised remain at the fringes. A recent report by the MyanmarInformation Management Unit (MIMU) on vulnerability bears out howthe reforms are failing the wider Myanmar population and exacerbatinginequalities (MIMU, 2018). This multi-sectoral review holds thatMyanmar’s success in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals(SDGs) largely depends on how well the government targets the poorestand most marginalised in society. In its summary findings, the reportpoints to the urban–rural differences as follows (MIMU, 2018: 2):Stark disparities were found in living conditions and economicfreedoms between the residents of urban and rural areas: 72% ofrural villages are not electrified and persons in rural areas havemarkedly lower access to safe drinking water and sanitation;educational outcomes vary significantly and secondary schoolattendance in rural areas is half of that in urban areas.Introduction1

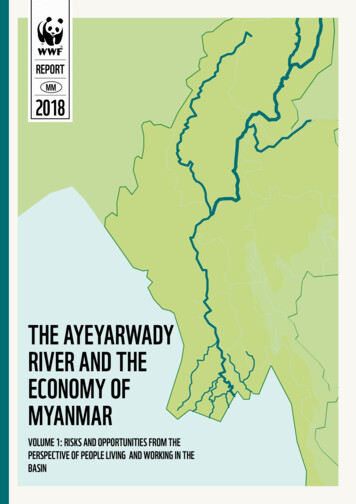

Figure 0.2 Map of Myanmar. Source: CartoGIS Services, College ofAsia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.

With regard to health, the report again shows the stark disparities thatare not being alleviated by the reforms (MIMU, 2018: 3):There are wide geographic, ethnic and socio-economic disparities;infant mortality rates are highest in the districts of Labutta inAyeyarwady and Mindat in Chin, whereas Magway, Sagaing andTanintharyi have particularly high early years mortality rates.Children in rural areas are more likely to be chronically undernourished (32% stunting) than those in urban areas (20%).With regard to education the report finds (MIMU, 2018: 3):Literacy is particularly low in Shan State which accounts for 18 ofthe 19 townships countrywide where more than half of childrenhave never attended school; Mongkhet township is especiallyprominent with 85% of children never having attended school.Other townships with particularly high numbers of persons withno education are in Kayin, Magway and Rakhine. Children fromrural families, poor or otherwise disadvantaged groups are lesslikely to transition from primary to secondary education, or tocomplete their secondary education.Much of this is of course the legacy of decades of junta rule, yet thedecade of reforms could have made a significant difference if developmentpriorities had targeted the most vulnerable – the poor and conflictaffected communities.In part, the types of development being prioritised is due to the international aid and development community, whose philosophy comes froma neo-liberal tradition, and who are driving the reform process. This hasresulted in too much being changed at once, with tight targets exceedingthe capacities of local departments and organisations. It has also resultedin large development contracts being awarded to Western firms who havelittle knowledge of Myanmar2 rather than supporting bottom-up grassrootscivil society and local NGOs who understand the local context.3 The kindof development taking place is nevertheless also due to the gap betweenNLD policy and priorities, between what was promised and what thisfirst NLD Government is actually delivering. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi haschanged the tune of the government, asking local people to look to eachother for help and support rather than to the state (McCarthy, 2019).While the reforms have not yet resulted in Myanmar adopting anoverall market approach to public services, including education, theIntroduction3

Myanmar Government ministries are adopting other aspects of neoliberalism – including the vocabulary of efficiency and effectiveness. The‘market’ is being looked at to offer choice to the urban middle classes.Some reforms are being rolled out to improve the lives of the majorityrural and poor population by improving the quality of the governmentservices, but Myanmar’s first democratic decade has seen a dramaticincrease in the inequalities between urban and rural, middle classesand poorer sections of society. This is disappointing to many Myanmarcitizens4 who had put all their hopes into Daw Aung San Suu Kyi andher NLD Government. They had not expected much from the UnionSolidarity and Development Party (USDP) Government led by PresidentThein Sein that ruled from 2011 to 2015 that was largely viewed as nomore than a political vehicle for the military. There was a clear expectationthat once the NLD obtained power, the country would be governed in amanner that would strive to bring equality and justice to all. Peopledid not use the term ‘social justice’, but in effect that is what they werereferring to when speaking about access to education and health andpublic services, no matter where they lived and from what ethnic groupthey originated.Today, the NLD has been in power for almost five years and peopleacross the country complain about having been let down. Some look forexcuses, for example, that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has not had a free handin governing the country, but must constantly appease the military. Yetmany know that the military contingent in parliament5 is not preventingDaw Aung San Suu Kyi from delivering on their hopes. In fact, there wasmore than hope, rather the many promises in the 2015 NLD electionmanifesto that all reflect the issues that one would group under ‘socialjustice’, even if this exact term was not used.6One of the overall promises in the NLD election manifesto (priority3 of 4) was: ‘To change the lives of our people, the NLD will strive fora system of government that will fairly and justly defend the people’(NLD, 2015: 4). With regard to ethnic affairs and peace the NLDpromises ‘solidarity with all ethnic groups’ and ‘principles of freedom,equal rights and self-determination’ (NLD, 2015: 5). This is also reflectedin the section in the Constitution (NLD, 2015: 6) where the NLDpromises: ‘to guarantee ethnic rights’ and ‘to defend and protect theequal rights of citizens’. In particular, the NLD mentions agriculturalworkers (NLD, 2015: 11) and states that ‘farmers’ rights and economicwell-being must be secure’. Workers (NLD, 2015: 14) are being promisedthe following:4MYANMAR’S EDUCATION REFORMS

‘We will establish opportunities for workers to develop their skillsand expertise.We will implement policies aimed at ensuring that workplaces aresafe and fair for all, and that workers receive an appropriate salary.No worker should be discriminated against, and every workershould receive equal compensation for equivalent work.Every worker shall have the right to freely establish and be part ofworkers’ organisations that protect their rights and benefits.We will end all forms of forced labour.’In order to secure these opportunities for workers and agriculturalworkers, the NLD promises to: ‘strive to establish access to electricityin all areas, both urban and rural’ (NLD, 2015: 19) and the urbanpoor, many of whom are migrants from conflict and disaster areas arepromised to be rehoused: ‘We will establish, as quickly as possible, aprogramme for the rehousing of homeless migrants, who have moved tothe cities as a result of natural disasters, economic opportunities, andland confiscation’ (NLD, 2015: 25). Women are also promised equality(NLD, 2015: 22): ‘We will strive to ensure that existing laws are implementedeffectively so that women in all sectors – whether government,business, or social – have equal rights with men.We will take action as necessary to end the persecution, insecurity,violence, and other forms of harassment and bullying suffered bywomen.We will work to ensure that female workers receive the samecompensation as their male counterparts for equivalent work, andthat there is no gender discrimination with regard to workplacepromotions.’And most importantly for this book, with regard to education (NLD,2015: 15), the NLD promises the following: ‘We will prioritise the needs of schools in less-developed areaswhere schools currently lack necessary facilities and equipment, inorder to make middle school and high school education moreaccessible to all.For the improvement of the quality of life of people with limitededucational qualifications, we will establish opportunities forIntroduction5

further education through programmes for continuing basic middleand high school study, and in-school and out-of-school vocationaltraining opportunities of equivalent standard.We will establish effective education services that do not place aburden on parents and communities.’As can be seen from the above, the 2015 election manifesto did indeedpromise social justice, despite the absence of this term.7 The social justiceframework cuts across the various chapters, as education is a key elementif one is to build a just and equal society, and it is crucial for other reformsto succeed. The fact that the promises made by the NLD go well beyondthe education sector strengthens the case this book is making.After the manifesto, the election: November 2015 –Myanmar’s first free and fair election since 19908On Sunday 8 November 2015, Myanmar went to the polls with morethan 90 parties contesting seats for the two houses of parliament aswell as the 14 state and regional assemblies. Despite the large numberof parties, all eyes were on the opposition NLD and the regime USDP.The NLD swept the polls. In order to control the government, the NLDneeded 67 per cent of the seats (or 329 seats), as 25 per cent wereallocated to unelected appointees of the military; but the NLD did farbetter than this, winning almost 80 per cent of elected seats. Crossingthis threshold meant that Myanmar could become a very differentcountry – it offered a policy window to transform Myanmar. The losingmilitary-based USDP was bitterly disappointed with the result, yetdespite this, neither the military nor the USDP tried to hinder the transferof power in any way.The elections were followed by an almost three-month transitionperiod during which time the old government was still in power. Thenew parliament convened only after the old parliament dissolved on30 January 2016. The NLD’s first task was to select a new President,as Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the NLD, was barred by theconstitution from the position due to her having sons with Britishcitizenship. To circumvent this restriction, Daw Aung San Suu Kyideclared that she would be ‘above the president’ in all the decisions – apromise she has kept. In any event, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s closechildhood friend Htein Kyaw9 was appointed to the presidency and thepost of ‘State Councillor’ was created for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.106MYANMAR’S EDUCATION REFORMS

The challenges faced by the National Leaguefor Democracy (NLD)After winning the election, the NLD’s first challenge was to developcordial relations with the military. Myanmar has mainland SoutheastAsia’s largest standing army, and the constitution guarantees their placein parliament, and together with their control over key ministries theyremain significant stakeholders in the political system. The NLD hadto find a way to cooperate with the Chief of Staff as well as the militarymembers of parliament (MPs). The NLD’s campaign pledge to alter theConstitution, and in particular change Article 436 which ensured aveto by the military for any constitutional change, was likely to bringthe party into conflict with the military leadership, and as such it wasquickly shelved.The second major challenge was to rule and administer the country.The NLD did not do much in this regard between 2012 and 2015 asthey had only 43 MPs. With the exception of wanting to change theconstitution, the NLD campaign was devoid of clear and detailed policypriorities, keeping things rather general and focusing on promising majorchanges. As seen above, the NLD manifesto did, however, promise togovern the country on the lines of social justice, promising to representthe poorest and most disadvantaged in society.The main challenge facing the new Myanmar Government at thetime of the transfer of power was addressing the country’s ethnic andreligious tensions. An ul

2.1 Rural government school, 2014 63 2.2 Education protests, 2015 72 2.3 Leadership and management seminars for informed decision making for the Ministry of Education, 2019 83 3.1 Monastic school, 2010 109 3.2 Monastic teacher training: Network of CCA trainers, 2010 114 3.3 Phaung Daw Oo Monastic School, 2010 teachers'