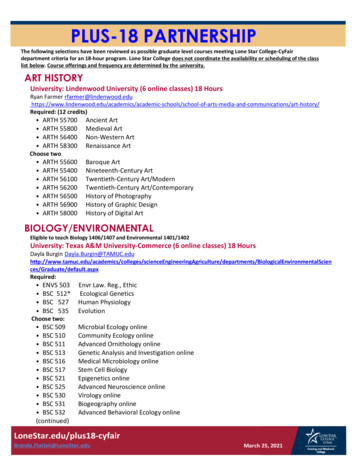

Transcription

SPRING 2017FINDING MENTALDISORDERS with MATHDefeating diabetes 12 Clearing the air 22 Promulgating PrEP 26

FIRST LOOKChallenges of studying malaria in the AmazonAMAZONIAN STARS Charles Harless 17MPH was one of the winnersof the Global Health Institute Student Photography Contest. He writesof this photo: A malaria research hut exudes light as the Milky Wayshines beautifully in the clear Amazonian night sky. In a region of theAmazon Basin classified by the national government as the “deepAmazon,” indigenous villages are small and spread out and lack runningwater and electricity. This makes studying the rampant malaria in theregion exceedingly difficult. In order to conduct its ongoing research,the Peruvian Institute for Infectious Diseases brings a small electricalgenerator to power their devices. Additionally, a simple light microscopeused to diagnose malaria strains is illuminated by a single standardheadlamp within the hut seen in this picture.Spring 20171

IN THIS ISSUEFEATURESDefeating diabetes 12Researchers tackle the epidemiclocally and globallySPRING 2017Finding mental disorders with math 18Clearing the air 22The Center for Biomedical Imaging Statisticsdevelops the complex analytical tools that allowbrain scans to be interpretedResearchers study indoorpollution from wood and coalburning cookstovesCOVER STORYLocator database makes findingand accessing HIV pre-exposureprophylaxis drug easierRollins Alumni AssociationAwards 29Promoting preventive health careand championing the underservedDEPARTMENTSJames W. Curran,MD, MPHAssociate Dean forDevelopment andExternal Relations,Rollins Schoolof Public HealthPhoto ContributorRollins magazine is published by the Rollins School ofAnn BordenPublic Health, a component of the Woodruff HealthEditorial ContributorSciences Center of Emory University (whsc.emory.edu).Dana GoldmanProduction ManagerCarol Pintoeditor, and other correspondence to Editor, Rollins, 1762Clifton Road, Suite 1000, Atlanta, GA 30322. Reach theeditor at 404-727-6799 or martha.mckenzie@emory.edu.MEd, 93MPHEditorKaron Schindlerkgraves@emory.edu. Visit the Rollins School of Publicthe magazine, visit publichealthmagazine.emory.edu.Peta WestmaasInterim AssociateVice PresidentHealth SciencesCommunicationsDesignerHolly KorschunMartha McKenzieArt DirectorLinda DobsonDirector ofPhotographyKay HintonAUN LOR 97MPHPlease send class notes, observations, letters to theExecutive DirectorHealth SciencesCreative ServicesKathryn H. Graves,CONTRIBUTIONS 32To contact the Office of Development and AlumniRelations, call Kathryn Graves at 404-727-3352 or emailDEAN’S MESSAGE 4CLIFTON NOTES 5Health website at sph.emory.edu. To view past issues ofEmory University is an equal opportunity/equal access/affirmative action employer fully committed to achievinga diverse workforce and complies with all federal andGeorgia state laws, regulations, and executive ordersregarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action.Emory University does not discriminate on the basis ofrace, age, color, religion, national origin or ancestry,gender, disability, veteran status, genetic information,sexual orientation, or gender identity or expression.17-RSPH-DEAN-0255Dean, Rollins Schoolof Public HealthYing Guo and her colleagues in the Center for Biomedical Imaging Statistics collaborate with researchers,many from the school of medicine, who are trying tounderstand the underlying brain anomalies of mentaldisoders. Illustration by Mario Wagner.Promulgating PrEP 26PHILANTHROPY 28IN MEMORIAM 30The recipient in 2002of the first MatthewGirvin Service Awardfor early leadership inpublic health, Aun Lorhas dedicated his life topublic health, humanrights, and ethics.The iPad edition of Rollinsmagazine is available bydownloading Emory HealthMagazines in the App Store.

FROM THE DEANCLIFTON NOTESOur continuing commitmentAs we move into the shifting policies and priorities that come witha new administration in Washington, D.C., it seems a good timeto reaffirm our commitment to our mission of promoting health,preventing disease, and reducing disparities at home and aroundthe globe. We advance that mission through conducting rigorousresearch that informs policy and interventions and through educatingthe next generation of public health leaders. We continue to view thework of public health as vital to the well-being of the global population.Our commitment to advancing the science of public health isunwavering, as evidenced by the work being done in our Center forBiomedical Imaging Statistics. Biostatisticians in the center developthe statistical tools that enable researchers to analyze the vast andcomplex data from today’s sophisticated brain scans. These tools haveallowed researchers to identify biomarkers of depression and othermood disorders and predict treatment outcomes, thus helping toreduce human suffering.When you view health as a basic human right, as we do atRollins, you are compelled to work to reduce disparities. Rollinsdiabetes researchers address this on several fronts. Diabetes affectsall countries, but the poorest countries and individuals are least ableto cope. Our researchers are seeing how well interventions that haveproven successful in the U.S. translate into low-resource settings.Closer to home, our researchers are heading a newly establisheddiabetes translation research center. One of the goals of the newcenter is to find ways to reduce the disparities in our own back yard,where younger, less affluent minorities with diabetes routinely faremuch worse than their older, more affluent, white counterparts.Rollins researchers are tackling a leading health risk factorof which most of us in the U.S. are totally unaware—indoor airpollution. The wood, dung, or crude charcoal burning cookstovesused in many homes across the globe blacken the lungs as well as thewalls. Rollins is leading a five-year, 30 million study on the impactof cleaner stoves and fuels.As much as we enjoy touting our research, educating tomorrow’spublic health researchers and practitioners is arguably our highestcalling. We are honored that Deborah McFarland, associate professorof global health, was recognized with the 2017 ASPPH TeachingExcellence Award. Deb joins five other Rollins faculty who havebeen honored with ASPPH teaching awards in previous years. Ourcontribution in training tomorrow’s public health leaders has perhapsnever been more important.Enjoy this issue of Rollins magazine and remain strong in yourfaith in the importance of the work that you do.James W. Curran, MD, MPHJames W. Curran Dean of Public Health4ROLLINS MAGAZINEA new target forParkinson’s diseaseRollins researchers have discovered a novel link betweena protein called SV2C and Parkinson’s disease (PD). Priorwork had suggested that the SV2C gene was associatedwith the curious ability of cigarette smoking to reduce PD risk.SV2C is part of a family of proteins involved in regulatingthe release of neurotransmitters in the brain. Dopaminedepletion is a well-known feature of Parkinson’s disease,and the research shows that SV2C controls the release ofdopamine in the brain.The team generated mice lacking the protein SV2C, whichresulted in less dopamine in the brain and reduced movement.The mice had a blunted response to nicotine, the chemical incigarette smoke thought to protect people from PD. In addition,when brains from patients who had died of PD, Alzheimer’sdisease, and several other neurodegenerative diseases wereexamined, they found that SV2C was altered only in the brainsof those with PD.“Our research shows a connection between SV2C anddopamine and suggests that drug therapies aimed at SV2Cmay be beneficial in PD or other dopamine-related disorders,”says Gary Miller, Asa Griggs Candler Professor, associate deanfor research at Rollins, and senior author of the study. nSpring 20172017 55

CLIFTON NOTESThe climate-health connectionEleven Emory faculty were among the 300 attendeesof the recent climate and health conference led byformer Vice President Al Gore at The Carter Center.Gore said more attention needs to be paid to thehealth consequences of climate change. nAt left, pictured l to r: Uriel Kitron (environmentalsciences), Stefanie Sarnat (environmental health),Eri Saikawa (environmental sciences), Karen Levy(environmental health), Carla Roncoli (anthropology), Tom Clasen (environmental health), PaigeTolbert (environmental health). Above: MattGribble (environmental health) and Al Gore.Collaborating to combat diet-related diseaseRollins faculty are part of a team that has received an award of 25,000 from General Electric to fight obesity, diabetes, andother diet-related diseases.The Southwest Atlanta Coalition for Healthy Living aims toimprove health outcomes by linking services at the HEALingCommunity Center, founded by Emory/Grady physician CharlesMoore, with nutrition and healthy eating programs at the WayfieldFoods store on MLK Drive in southwest Atlanta.The coalition will train Wayfield employees on healthy eatingand food preparation. These “health ambassadors” will assistshoppers with making healthier food purchases, linking them withother in-store programs, and providing information on servicesat the HEALing Community Center. The center will providenutrition prescriptions for healthy foods to patients.Representatives from Rollins will support the process throughtraining health ambassadors and evaluating the program.Southwest Atlanta is one of the city’s most under-resourcedareas. More than half of the community’s population lives belowthe poverty line and 98 percent of its children qualify for free orreduced lunches.6ROLLINS MAGAZINE“This pilot project creates a continuum of care that reachesfrom the clinic into the community and back again,” says AmyWebb Girard, an assistant professor of global health. “Engagingthe community in healthy decision-making won’t stop whenthey leave the clinic. In creating a supportive environmentwithin the community, we aim to make the healthier optionthe easier option.” nTo boldly go where publichealth hasn’t gone beforeRollins researchers will soon take their research into orbit, partneringwith the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in anew satellite mission to study air pollution.NASA chose Rollins as a joint recipient of its 100 million award— 2.3 million of which will come to Rollins—to study the effects of air pollutionon the population through a satellite mission, according to Yang Liu, associateprofessor of environmental health. He noted that this is the first time a NASAspace mission has incorporated a public health component.“We’re the scientific guinea pig,” Liu said.The Rollins research group, led by Liu, co-created the project idea withNASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). The mission will construct and use aMulti-Angle Imager for Aerosols (MAIA) device to record airborne particulatematter, which will collect data on the effects of pollution on public health fromat least 10 locations with major metropolitan areas.Once constructed by JPL, the MAIA device will be mounted on a compatibleEarth-orbiting satellite. “Even though it’s a small mission, it’s actually the firstever in which we get to work with NASA engineers to build public health intothe DNA of this instrument,” Liu said.The Rollins team will analyze the data to make predictions about publichealth issues such as birth outcomes and cardiovascular disease. The team willalso serve as the public health liaison between JPL and other institutions in thecomplete research group. Recruited by Liu, the complete group has teams atUniversity of California, Los Angeles, Harvard University, University of BritishColumbia, and University of Dalhousie.Because the device will orbit via satellite, it will provide a more holistic view ofair pollution data than the commonly used ground monitors.“It’s very difficult to cross to a completely different scientific community andconvince them that this mission is not only worthwhile but also feasible,” Liusaid. “Hopefully, Emory will make a mark in NASA history.” nK.M. Venkat Narayan hasbeen elected to the NationalAcademy of Medicine. Electionto the NAM is considered oneof the highest honors in thefields of health and medicineand recognizes individuals whohave demonstrated outstandingprofessional achievement andcommitment to service. Narayan,the Ruth and O.C. HubertProfessor of Global Health inthe Hubert Department of GlobalHealth and director of the EmoryGlobal Diabetes ResearchCenter, is one of the world’sleading researchers on type2 diabetes.Prior to joining Rollins,Narayan spent 10 years at theCenters for Disease Controland Prevention, leading scienceefforts in his role as chief ofthe diabetes epidemiology andstatistics branch. He was alsoan intramural researcher at theNational Institute of Diabetesand Digestive and KidneyDiseases and worked on thefirst diet-exercise interventionstudy in the Pima Indians.Narayan is the 11th primaryor jointly appointed Rollinsfaculty member to be electedto NAM. nSpring 20177

CLIFTON NOTESmultiple federalagencies, includingNIH, CDC, andthe NationalInstitute on DrugAbuse. The goalwas to fostercollaborationson research andinterventions.“People are alreadystarting to puttogether proposalsthat grew out of theconference,” saysCooper, associateprofessor and vicechair in behavioralsciences and healtheducation. “We will continue to check in withthe working groups that have formed and seehow we can support them going forward.”Investigators also connected withfunders, gaining valuable insight into theirpriorities. Although there is uncertaintyabout public health spending under thenew administration, federal funders at theconference were eager to support researchers’efforts. “There is actually bipartisan supportfor addressing the opioid epidemic as apublic health crisis now,” says Cooper. “That’spartially because the opioid epidemic ishitting areas that have historically votedRepublican—Southern and rural counties.”Funding for the conference came from theEmory Conference Center Subvention Fund,which is awarded by the university’s Centerfor Faculty Development and Excellence. nConference confronts South’sopioid epidemicThe opioid epidemic that is ravaging thecountry is hitting some areas of the Southparticularly hard. The region is experiencingdramatic increases in rates of overdoses,hepatitis C, and neonatal abstinencesyndrome. Concerns about possible futuretrajectories for the Southern epidemic arehigh because the region has historicallyinvested less in its public health and drugtreatment infrastructure than other regions.To begin to address the epidemic, Rollinshosted a two-day conference, “The SouthernOpioid Epidemic: Crafting an Effective PublicHealth Response.” Organized by HannahCooper, with colleagues from New YorkUniversity, Vanderbilt, and the Universityof Arkansas, the conference drew academicresearchers, state and municipal healthdepartment scientists, and leaders fromBY THENUMBERSThe amount ofprescription opioidssold in the U.S. nearlyquadrupledsince 1999. —CDC12 stateshave more opioidprescriptions thanpeople, 7of theseare in theSouth—Alabama,Kentucky, Louisiana,Mississippi, SouthCarolina, Tennessee,West Virginia. —CDC33,091Americans diedfrom drug overdosesStudy determines how long Zikaremains in body fluidsThe Zika virus remains in semen longer than it does in blood,urine, and other body fluids, according to a recent studypublishedin The NewEngland Journalof Medicine. Thestudy, led by theCDC and includingRollins researchers,looked at men andwomen in PuertoRico who wereinfected with Zika.Half of theparticipants haddetectable virus particles in semen one month after the start ofsymptoms and 5 percent after three months. By comparison, halfhad Zika in their blood after 14 days and 5 percent at 54 days. In urinespecimens, half of the participants had virus particles at eight days and5 percent at 39 days. Regarding vaginal fluids and saliva, Zika virusparticles were largely undetectable after one week.“The findings of this study are important for both diagnostic andprevention purposes,” says Eli Rosenberg, assistant professor ofepidemiology and scientific co-investigator of the study. nin 2015. —CDC 55 billionin health and socialcosts are related toprescription opioidabuse each year.—U.S. Departmentof Health and HumanServicesNeighborhood safety and activity“Creating the Healthiest Nation: Climate Changes Health”American Public Health Association’s 2017 annual meeting will be in AtlantaSave the Date NOV 4 – 8, 20178ROLLINS MAGAZINEWhen parents believe their neighborhood is unsafe, theirchildren are less active. Specifically, these children engagein nearly one less day per week of physical activity than theircounterparts in neighborhoods that are perceived as safe.“Physical activity is vital for the health, growth, andsocial development of children,” explains Karla Galaviz, aresearcher with the Emory Global Diabetes Research Center.“Physical activity interventions should consider parental safetyconcerns and economic disparities.” nRole of person-to-personspread in drug-resistantTB epidemicSouth Africa is experiencing a widespreadepidemic of drug-resistant tuberculosis(XDR TB), the deadliest form of TB. Personto-person transmission, not just inadequatetreatment, is driving the spread of the disease,according to a study published in The NewEngland Journal of Medicine and writtenby Neel Gandhi, associate professor ofepidemiology and global health.The study identified numerousopportunities for transmission not only inhospitals, but also in community settings,such as households and workplaces. This hasimportant implications for efforts to preventthe disease, which have traditionally focusedon ensuring that patients receive accurateand complete TB treatment.“These findings provide insight as to whythis epidemic continues despite interventionsto improve TB treatment over the pastdecade. Public health and research effortsmust focus more intensely on identifying andimplementing additional or new interventionsthat halt transmission,” says Gandhi.Drug-resistant TB is a significant globalepidemic. Reported in 105 countries, XDR TBis resistant to at least four of the key anti-TBdrugs. In most settings, treatment is effectiveless than 40 percent of the time, with deathrates as high as 80 percent for patients whoalso have HIV. nSpring 20179

CLIFTON NOTESMapping HIV by state, country, metroThe South is generally known as a hot zone for HIV/AIDS,but a recent study by Eli Rosenberg, assistant professorof epidemiology, breaks down for the first time HIV ratesfor men who have sex with men (MSM) by state, county,and metropolitan area. The cities with the highest ratesincluded Columbia, S.C.; El Paso, Texas; and Jackson, Miss.In these cities, more than 25 percent of MSM had beendiagnosed with HIV, as compared with the national averageof 15 percent.“This is really the first time we’ve been able to examinethe HIV infection burden at such fine levels of geography,”says Rosenberg.His study found that six states exceeded the nationalaverage of MSM diagnosed with HIV in 2012—and all of themwere in the South. Of the top 25 metro areas in terms ofprevalence, 21 were south of the Ohio River.Why the high concentration in the South?Although Rosenberg’sstudy is purelyepidemiologic, hesays that the researchnaturally leads to someeducated guesses aboutthe reasons behind thetrend. It could be that theSouth is, by and large,Eli Rosenbergpoorer and more rural,with worse public transit and less access to adequate testingor care than other parts of the country. Then there is thecultural and religious bias that abounds in the region—thestigma attached to homosexuality, HIV/AIDS, and race.The next step, Rosenberg says, is to incorporate otherdata resources that would break the map down further—by age, education, poverty, and race. nMEDIA SAVVY“It’s called theperfect pathogen.”Christine Moe,director of the Center forGlobal Safe WASH, told WSJVideo about the norovirusstomach bug.“Elections haveconsequences,the saying goes. Itwould be awful ifone consequenceof the last onewas potentiallythousands ofpreventablechildhood deaths.”Saad Omer,William H. Foege Chair in GlobalHealth, wrote in a WashingtonPost opinion piece aboutPresident Trump’s theoriesabout vaccines.“In terms of bangfor the buck,it’s one of themore valuablecancer screeningservices.”David Howard,Prevalence of HIV diagnoses among men who have sexwith men (MSM) per 100 MSM, by U.S. states and District ofColumbia, 2012.10ROLLINS MAGAZINEprofessor in Health Policy andManagement, told CNN aboutcolonoscopies.Students launch advocacy seriesOn a bright, unseasonably warm late Februaryafternoon, dozens of Rollins students passedup the opportunity to sit in the sun or sharea laugh with friends. Instead, they gatheredin a classroom to listen to a representativefrom the Georgia legislature give tips abouthow to lobby effectively.“In this political climate, I feel like it’simportant for me to learn how to advocate forissues that are important to me,” says Anna Shao18MPH, who attended the event.State rep. retinna shannon gaveThe seminar, “Lobbying 101,” was the secondtips on effective lobbying.event in the student-led Rollins Advocacy Series.The series grew from student concern after thepresidential election. After being approached several times by students lookingfor opportunities to learn advocacy skills, Rollins Student Government Associationpresident Tina Mensa-Kwao 18MPH reached out to the leaders of the other Rollinsstudent organizations. Together, they cobbled together the series, which kickedoff in mid February with a seminar titled “What is Advocacy?”Several other events are scheduled, each organized by a different studentorganization. Topics include environmental justice, advocacy in public healthemergencies, and the local legislative process. The series also includes an effortevery Thursday during lunch called “Tabling for Change.” A table is manned bya student who encourages fellow students to call their representatives. Samplescripts on various topics related to public health are available, along with a list ofall state representatives and their phone numbers.“I am thrilled the students are organizing these workshops,” says Karen Andes,assistant professor of global health, who spoke at the first seminar. “They are asking the same questions that many of us are right now—what can we do?”The series will run through the end of the semester, and then Mensa-Kwaoand other student leaders will see if there is demand to continue it. nMcFarland honored for teaching excellenceDeborah McFarland, associate professor of globalhealth, was awarded the 2017 ASPPH TeachingExcellence Award. The Association of Schools andPrograms of Public Health, in conjunction with PfizerInc., gives awards to graduate public health facultywho are noted for their excellence in teaching, research,and mentorship. McFarland is the 10th Rollins facultymember to garner an ASPPH award, six of which(including McFarland) are for excellence in teaching.Rollins faculty have also been recognized for publichealth practice, research, and student services. nSpring 2017 11

REDEFINING THE UNACCEPTABLEWHEN K.M. VENKAT NARAYAN FIRST BEGAN STUDYINGTYPE 2 DIABETES IN THE EARLY 1990S, IT WAS CONSIDEREDA DISEASE OF ADULTS IN AFFLUENT COUNTRIES.Today diabetes has spread to every country in the world, to both urbanand rural areas. It afflicts the poor as much as if not more than therich and strikes children and teens as well as adults. A possible newphenotype of type 2 diabetes has emerged that is affecting younger,What it will take toDefeat DiabetesByM a rt h a M c K e n z i e I l lu s t r at i o n s b ythinner people.The number of people with diabetes has quadrupled from 1980 to2014, and 415 million adults in the world now have diabetes, accordingto Rollins researchers. Globally, it was estimated that diabetesaccounted for 12 percent of health expenditures in 2010, or at least 376 billion—a figure expected to hit 490 billion in 2030.S te ph a n i e Da lto n C owa n“In the years since I began working in this field, diabeteshas grown to become one of the biggest public health threatswe face,” says Narayan, Ruth and O.C. Hubert Professor ofGlobal Health. “The spread of some of the ills of a modernlifestyle—sedentary behaviors, a diet of processed andunhealthy foods, and an increase in obesity—has madediabetes a worldwide crisis. And at least in its most commonform, it is substantially preventable.”Narayan and his team of researchers in the Emory GlobalDiabetes Research Center are looking at what needs to bedone to reach a world free of diabetes.First-world problemsIn the U.S. and other high-income countries, diabetes is a121212 ROLLINSROLLINSROLLINSMAGAZINEMAGAZINEgood news, bad news scenario. On one hand, people whohave diabetes today fare better than they did 20 years ago.They are living longer and suffering fewer complications,such as heart disease, kidney disease, amputations, strokes,and blindness.On the other hand, more people are developing diabetesthan experts even projected, with some 29 million peoplein the U.S. living with the disease today. One in four peoplewith diabetes remains unaware and almost 90 percent withprediabetes don’t know their blood sugar is elevated. Andthe drop in complications is not enjoyed equally. Minorities,people with low incomes, and younger adults tend to suffermore than their white, affluent, and older counterparts.“We have gotten very good at caring for and controllingSpring 2017 13

REDEFINING THE UNACCEPTABLEChanging HIV risk behavior was prettychallenging, but sexual behavior isepisodic. However, you eat mealsthree times a day, so you havemore opportunities to succeedor fail each day.- Ralph DiClementeMohammed Ali, far left,and Ralph DiClementecollaborate in the translationresearch center. K.M.Venkat Narayan. right,heads the Emory GlobalDiabetes Research Center.diabetes, but we are lagging in prevention,” says Narayan.“The science is there. We know exercise, a healthy diet,and weight loss are extremely effective in preventingdiabetes in people at high risk, but we haven’t been ableto figure out how to translate and scale up the implementation of that knowledge into population-wideinterventions that work. We also need to find ways toimprove outcomes for disenfranchised populations.”Narayan and his team will be tackling these issuesthrough the newly established Georgia Center forDiabetes Translation Research. The center isfunded by a grant from National Institute ofDiabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseasesthat was awarded to a partnership of EmoryUniversity (Rollins as well as the schools ofmedicine, nursing, and business), GeorgiaInstitute of Technology, and MorehouseSchool of Medicine. Narayan is the principalinvestigator of the center.Narayan and his team are borrowing theexpertise Rollins has built in HIV prevention bybringing in Ralph DiClemente, Howard CandlerProfessor of Public Health in behavioral sciencesand health education. DiClemente has decades ofexperience working to prevent risky sexual behavior among populations vulnerable to HIV, and hewill repurpose these strategies to prevent diabetes.“One of the key things we’ve learned in our HIVwork is that knowledge of the disease and what ittakes to prevent it, while necessary, are not enoughto promote adoption or maintenance of behavior14ROLLINS MAGAZINEMAGAZINEchange,” says DiClemente. “We need to do much more thanletting people know they are at risk. We have to be able tomotivate people to adopt healthy behaviors.”That task may prove even more difficult for diabetes thanit is for HIV. “The risk for both lie in lifestyle behaviors—sexual behavior for HIV and diet and exercise for diabetes,”says DiClemente. “Changing HIV risk behavior was prettychallenging, but sexual behavior is episodic. However, youeat meals three times a day, so you have more opportunitiesto succeed or fail each day.”Technologies such as text messaging apps have provenhelpful in providing needed reminders and motivation in HIVinterventions, and the center plans to deploy similar strategiesto fight diabetes. Community strategies can provide anotherlayer of support. Coaches at YMCAs, churches, and communitygroups could be trained to offer diet and exercise interventions.The center will also focus on eliminating disparities in diabetes management and complications, for which its Georgialocation is ideally suited. The prevalence of diabetes in theSoutheast is much higher than in other parts of the country—running 13 percent to 15 percent as compared to 9 percentfor the nation. It also strikes some groups harder than others,particularly afflicting African Americans, people with lowerincomes, and those with lower education levels. Not only dothese groups have a higher incidence of diabetes, they havehigher complication rates and incur higher costs.Once again, the center will benefit from the expertise ofthe larger institution. “We have a lot of experience in disparities we can draw from,” says Mohammed Ali, associateprofessor of global health and epidemiology and associatedirector of the center. “The school of medicine has a recentlyawarded American Heart Association Cardiovascular Centerfor Health Equity, and our epidemiology department has atraining grant that focuses on disparities in cardiovasculardiseases. These centers will collaborate, as their missions aresimilar, and the hope is that, together, the impacts will belarger than the sum of their individual actions.”Ali and his team have also identified another high-riskgroup—young adults. People with diabetes between 18 and44 routinely have the worst outcomes in terms of controllingglucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol. That’s largely becausethis group is not good at getting the care they need. “Youknow how the young never show up to vote? The young alsodon’t show up for diabetes care,” says Ali. “We’re not sure wh

The climate-health connection Eleven Emory faculty were among the 300 attendees of the recent climate and health conference led by former Vice President Al Gore at The Carter Center. Gore said more attention needs to be paid to the health consequences of climate change. n At left, pictured l to r: Uriel Kitron (environmental