Transcription

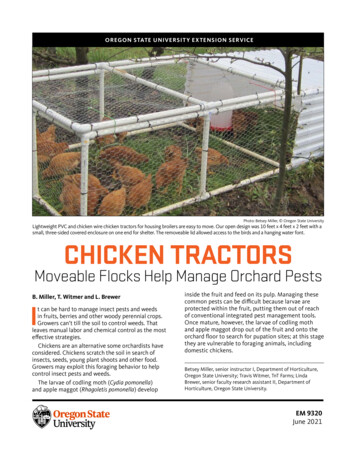

OREGON STATE UNIVERSIT Y EXTENSION SERVICEPhoto: Betsey Miller, Oregon State UniversityLightweight PVC and chicken wire chicken tractors for housing broilers are easy to move. Our open design was 10 feet x 4 feet x 2 feet with asmall, three-sided covered enclosure on one end for shelter. The removeable lid allowed access to the birds and a hanging water font.CHICKEN TRACTORSMoveable Flocks Help Manage Orchard PestsB. Miller, T. Witmer and L. BrewerIt can be hard to manage insect pests and weedsin fruits, berries and other woody perennial crops.Growers can’t till the soil to control weeds. Thatleaves manual labor and chemical control as the mosteffective strategies.Chickens are an alternative some orchardists haveconsidered. Chickens scratch the soil in search ofinsects, seeds, young plant shoots and other food.Growers may exploit this foraging behavior to helpcontrol insect pests and weeds.The larvae of codling moth (Cydia pomonella)and apple maggot (Rhagoletis pomonella) developinside the fruit and feed on its pulp. Managing thesecommon pests can be difficult because larvae areprotected within the fruit, putting them out of reachof conventional integrated pest management tools.Once mature, however, the larvae of codling mothand apple maggot drop out of the fruit and onto theorchard floor to search for pupation sites; at this stagethey are vulnerable to foraging animals, includingdomestic chickens.Betsey Miller, senior instructor I, Department of Horticulture,Oregon State University; Travis Witmer, TnT Farms; LindaBrewer, senior faculty research assistant II, Department ofHorticulture, Oregon State University.EM 9320June 2021

particularly broilers, are a useful way to reduce pestsand weeds.The aim of this study was to investigate thefeasibility of integrating poultry into an organic appleorchard, and to understand the contribution of poultryto manage insects and weeds. The study was conductedover 13 months beginning in April at BrooklaneSpecialty Orchard in Benton County, Oregon. Whileour results were not as promising as our optimism, ourfindings indicate that chickens can be a useful tool ina home orchard or a commercial setting where poultryare already part of the overall production scheme.CHICKE N TR AC TOR DESIG NChicken tractors have been designed largelyfor pasture settings. Tractors allow the foragingchickens to be moved around the pasture whileremaining contained. The study orchard hadbeen established and pruned to produce fruiton low branches. To fit under the trees, ourchicken tractors were built to a lower profile.Figure 6 shows a model that is practical underfruit and nut trees. A design that works wellin one setting may not work as well in others,so you may wish to customize your chickentractor. A good chicken tractor should: Experimental designBe durable and lightweight.Provide protection from the elements.Provide access to feed and water.Provide 1.5 to 2 square feet of space per bird.We conducted two separate experiments indifferent areas of the orchard, one using broilers forinsect and weed control, and one using laying hens.We chose ‘Red Ranger’ broilers and ‘Leghorn’ and‘Black Copper Maran’ laying hens for this projectbecause these breeds are known to thrive in apasture setting and have an energetic temperament,which leads to active foraging. All growing animalsare hungry, and their diets must provide for theirgrowth needs. The more mature layers requiresufficient nutrients for their maintenance andreproductive needs.No herbicides were applied to any of the study alleys.The baseline and post-foraging percentages of weedcover were assessed by visual estimates. In this study,every plant growing within the tree row was countedas a weed and categorized as a grass or a broadleaf.Because both types of chickens received supplementalfeed, and because their manure was deposited directlyon the orchard floor, we assume that the chickenscontributed to subsequent weed populations. Forthe broiler trial, percent weed cover within a rowwas assessed before chicken tractors were deployed,directly after they were removed from the orchard andFor other chicken tractor designs, see“Resources,” page 7.4'4'2'10'Thisschematicshows thedimensions of the chickentractor we designed for use in alow-canopy orchard. The frame in our designwas constructed of PVC, which is lighter thanwood but requires more structural support.The top wire mesh panel was removable toallow access to the birds.Graphic: Betsey Miller, Oregon State UniversityCertain breeds of poultry feed voraciously on insects,weed seeds and seedlings. Australian researchersreported that poultry (breed unknown) were moreeffective than insecticides at suppressing apple weevilpopulations. Similarly, in a French study, free-range‘Label Rouge’ (‘Red Label’) chickens reduced weevilpopulations in a peach orchard and eliminated weeds.We deployed broilers and laying hens againstlarvae and pupae of moths and flies as well as weeds.Broilers were held in chicken tractors — movablehousing — within the orchard. Layers were penned intolarger areas of the orchard. We found that chickens,Photo: Betsey Miller, Oregon State UniversityWeed cover was assessed as a visual estimate of percentcoverage within a square-meter quadrat. Each plant within thequadrat was classified as a grass or a broadleaf.2

Photo: Betsey Miller, Oregon State UniversityWe housed laying hens in a modified chicken tractor that was covered and enclosed on all four sides and included a roosting site forsleeping. A small door gave the hens access to the foraging area, which was surrounded by electric fence. This low-profile design wastailored to our trial site; the trees had been pruned to produce fruit low to the ground.one year after the foraging treatment was initiated. Forthe layer trial, percent weed cover within a row wasassessed before introduction of the hens, then after sixweeks, 12 weeks and 18 weeks of foraging. Althoughwe do not present the data here, we have evidence thatmulching the orchard floor after the chickens movedthrough improved subsequent weed control.Layer experiment design Layers were penned into a tree row with electricpoultry netting, but otherwise allowed to rangefree under the orchard canopy. These rows hadnever been treated with broilers in chickentractors. The 48-inch high netting was electrified with asolar fence charger and was attached to built-inposts.Broiler experiment design Broilers were brought into the orchard at 3 weeksof age and were processed at 12 weeks. Movable chicken tractors housed 25 birds andwere placed within a tree row on April 1. Wedeployed four chicken tractors in one acre oforchard. Each tractor was moved down an orchard row everytwo to three days. Broilers were removed from the orchard forprocessing on June 1. We did not introduce asecond cohort of broilers. National Organic Program standards prohibited usfrom applying chicken manure for three months beforefruit harvest. Had we introduced a second cohort ofbroilers, the three-month waiting period would haveput apple harvest after Nov. 1. Many Pacific Northwestvarieties are harvested before that date. Each pen contained a low-profile coop withnesting boxes and shelter from weather andpredators. Each of four pens was stocked with 10 layers,for a total treatment area of about one-half anacre. Layers were introduced in November when theywere at least 1 year old and remained in theorchard until the following March. Layer pens were moved within the trial areaapproximately every six weeks. Broilers and layers were provided with larvaeand pupae of nonpest species representingcodling moth and apple maggot larvae andpupae. Nonpest species were used to reducerisk of infestation in the orchard.3

Photo: Betsey Miller, Oregon State UniversityFor the free-range layers, the insects were placed into a shallow tray buried at the soil surface. A tarp under the mulch layer preventedthe insects from escaping.Photo: Betsey Miller, Oregon State UniversityPhoto: Betsey Miller, Oregon State UniversityThe tray was placed at night to avoid attracting the birds’attention. The tarp and the tray were for research purposes onlyand are not recommended insect control methods.Broilers were provided with insect larvae and pupae mixed intodeciduous leaf mulch.Larvae and pupae were mixed into soil and leaf litter,which was spread over a tarp or buried to ground levelin a shallow tray, which prevented the larvae fromescaping into the soil. Tarps or trays were removedafter 24 hours. All leaf litter and soil was sifted torecover any remaining insects.All chickens were provided with sufficient water andfeed to supplement their foraging activities. The broilers proved to be voracious consumers ofthe larvae and pupae provided, consuming nearly99% of insects provided from the age of 4 weeksand older. Layers had a greater area over which to range, and agreater choice in foraging locations. Layers spent the winter out of doors. Theyconsumed 90% of the insects provided inNovember but less than 40% of the insectsprovided thereafter. This reduction may havebeen due to reduced activity levels or due topredation against the layers themselves, whichalways increases in the winter. Chickens that arewatching for predators are less able to concentrateon scratching. We did not measure how muchsupplementary feed they consumed.Key findings: insectsWe compared the percent recovery of insectsbetween plots with and without chickens. Neither broilers nor layers showed significantpreference for larvae vs. pupae. Broilers showed asignificant preference for moths vs. flies.4

CHICKEN VS . PREDATORPredation of chickens by wildlife can reducethe flock to a suboptimal density for pest control.The layers in our study were much less shelteredthan the broilers, and they foraged during thewinter, when predation pressure was greater.Within their managed free-range row, the layersexperienced significant predator pressure.Principal predators in this Willamette Valleystudy were hawks, foxes and raccoons. Opossumsand rodents also prey on chickens. The study orchard was bordered on one side by a creek. Foxesand raccoons, especially, travel creek systems.Electrified fencing did not prevent the loss oflayers from ground-based predators. Similarly,providing cover and reflective discs did notprevent loss from aerial predators. The predationrate on layers approached 37% by March.Only hens were deployed in our study, although roosters have been shown to protecttheir flocks from predatory birds. Roosters alsocause the hens to spread more evenly across thesite, which would have impacted both weeds andinsect pests.Key findings: weedsBroilers Broilers significantly reduced total weed coverinside the chicken tractor and in the orchard rowafter nine weeks of foraging. After foraging, the portion of the treatmentarea covered by grasses decreased by 9%. In theuntreated control, coverage by grasses increasedby 23%. Foraging had no significant effect on broadleavedweeds. One year after the foraging treatment wasinitiated, there was no significant differencein weed coverage between foraged anduntreated areas.Photos: Betsey Miller, Oregon State UniversityReduction in weed coverage immediately following foraging bybroilers (top photo) and layers (bottom) was evident. From November to March, layers reduced groundcover by less than 10%. In the untreated control, grass and broadleafcoverage each decreased by 14%. It is possiblethat supplemental feed contributed to grassy weedcoverage in foraged areas. It may have been that laying hens preferred onearea over others for protection from weather orpredators and provided uneven weed and insectcontrol.Layers Though layers reduced ground cover in the shortterm, long-term effects were not significant. By February, foraging layers had reduced grassesby 33%, while in untreated areas, grassesincreased by 9%. By March, there was nodifference in ground cover between foraged anduntreated areas.5

Chicken tractors:Are they right for you?Convert chicken density fromacreage to your home orchardSome readers might apply this concept to ahome orchard on an urban lot. Here’s how tocalculate the stocking rate if you are working withsquare feet, rather than acres. 1 acre 43,560 square feet. The square footage of the orchard is thelength times the width. Divide the treatment area by 43,560. Multiply this quotient by 200. This willprorate the density of poultry for yourorchard.Home orchard, highly diversified small farm, orcommercial orchard — the integration of chickens intoany of these will require careful thought and a clearstatement of the goal of the enterprise.Initially, we wanted to identify whether chickenrental for insect and weed management could be aservice, as goats or sheep are rented out for weedmanagement. However, goats and sheep are valuedfor their ability to produce meat and milk from lowquality forages. The plants the property owner wishesto manage with grazing may often be of low quality. Bycontrast, chickens require higher-quality, often grainbased feeds to produce meat and eggs.Other considerations for integrating chickens into anorchard: How many eggs layers can produce: Productionslows or stops altogether in winter withoutsupplemental lighting; layers produce eggs fromaround 6 months of age up to 5 years. The market price for eggs and the volume of eggsnecessary to break even. The quantity and quality of supplemental feed. The replacement cost of birds lost to predation. The predator population on your property, andyour ability to provide secure housing. How chickens will complement other pestmanagement strategies in your orchard. The availability of labor to tend to the chickens,gather eggs or process the chickens at slaughter.Example: I want to put chickens into anorchard that is 20 feet x 80 feet on my urban lot.How many chickens should I provide?1. Compute the area of your home orchard:20 80 1,600 square feet2. Divide the area of your orchard in square feetby the number of square feet in an acre:1,600 43,560 0.0367In this example, my home orchard is about4% of an acre. I rounded up from 0.367 toget 0.04.3. Multiply 0.04 (the portion of an acrerepresented by my orchard) by 200 (thedensity of chickens per acre):0.04 x 200 8In this example, eight chickens should beenough to manage weeds and insect pests.In this project, we established stocking ratesof broilers and layers as a means of providingpartial insect and weed control in apples. Weproject that the results would be similar in othertree fruit crops. We established that broilers inthe spring were voracious feeders on moth andfly larvae and pupae, and that they providedshort-term reduction in weed control. Mulchingthe orchard floor after removing the broilers’chicken tractors provided longer-term weedcontrol. Older laying hens required more space(resulting in lower stocking rates), did not forageas heavily in winter, and suffered significantpredation in winter. In this setting they did notperform as well as broilers in pest and weedcontrol. Although broilers are effective at pestand weed control, they are not cost-effective as astand-alone strategy. However, they can integratewell into a home orchard or a commercial settingwhere chickens are already a desired element ofThe research density for broilers was 100 birds peracre; that density cost us 11.05 per bird for nineweeks of insect and weed reduction. The commercialscale of 200 birds per acre would have reduced the costto 7.47 per bird and increased pressure against weedsand insects. Placing a second group of 3-week-oldbroilers in the orchard on June 1 would have produced12-week-old broilers in early August. This would havechanged the profit potential for broilers and increasedforaging pressure against weed and insect pests.Layers are larger birds requiring more space. At theresearch stocking rate of 80 layers per acre, laying hensas orchard insect control cost us 5,900 per acre. Thisnumber would have been somewhat reduced if we hadsubtracted the cost of insecticides not applied, butthat would not have offset the losses. It may be thatyounger layers put out in the spring would improvethese numbers. Orchardists of any scale who alsokeep chickens will see a benefit from this practice, butwe cannot claim that chickens will be a profitable orcomplete pest management solution.6

ResourcesJacob, J. Normal Behaviors of Chickens in Small andBackyard Poultry Flocks. 2015. University of Kentucky.eXtension: -flocksAnnala, D., B. Tuck, S. Kerr, E. Hammond and S. Olson.2014. Living on the Land: Backyard Chicken CoopDesign. EC 1644. Oregon State University ExtensionService, Corvallis, Oregon. ight, C. A Quick Guide to Raising PasturedBroilers. 2020. Pennsylvania State UniversityExtension Service. -pastured-broilersBush, M.R., M. Klaus, A. Antonelli, C. Daniels.Protecting Backyard Trees from AppleMaggot. 2005. Washington State UniversityExtension. -apple-trees-from-apple-maggotsThe Livestock Conservancy. Leghorn (Non-Industrial)Chicken. e/internal/leghornCazaux, L. “Mixed Orchard Animals and MixedOrchard Vegetables Systems.” 2015. Master’s thesis,Norwegian University of Life Sciences. .pdf?sequence 1(USDA) 1999. Crop Profile for Apples in Oregon.United States Department of Agriculture. es.html.Accessed Nov. 15, 2011.Washington State University Extension Service.Pastured Poultry. Organic Farming Systems andNutrient Management. Darre, M.J. Almost Everything You Need to Know AboutRaising Broiler Chickens. University of sDetweiler, A.J. Life Cycle of the Codling Moth. ses/insects/life-cycle-codling-mothHilaire, C., Mathieu, V., Joly, T., Mirabito, L. 2001.Against pests of peach: ‘red label’ chickens, a selective natural enemy. Infos – CTIFL, 170: 38-40.Facts and Figures. 2019. Oregon Department ofAgriculture. http://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics byState/Oregon/Publications/facts and figures/factsand figures.pdf.Yates, L., Spafford, H., Learmonth, S. 2007. Apple weevil(Otiorhynchus cribricollis) management and monitoring in Pink Lady orchards of south-west Australia.Plant Protection Quarterly, 22: 155-159.Fernandez, D. and C. Sanders. Is using goats, sheepto control weeds and brush right for you? 2014.University of Arkansas Cooperative ExtensionService, Pine Bluff, Arkansas. owledgment: This pilot study was funded by the Agricultural Research Foundation, Oregon State University.This publication will be made available in an accessible alternative format upon request. Please contact puborders@oregonstate.edu or1-800-561-6719. 2021 Oregon State University. Extension work is a cooperative program of Oregon State University, the U.S. Department ofAgriculture, and Oregon counties. Oregon State University Extension Service offers educational programs, activities, and materialswithout discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexualorientation, disability, age, marital status, familial/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs,genetic information, veteran’s status, reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.)Oregon State University Extension Service is an AA/EOE/Veterans/Disabled.Published June 20217

Layers were penned into a tree row with electric poultry netting, but otherwise allowed to range free under the orchard canopy. These rows had never been treated with broilers in chicken tractors. The 48-inch high netting was electrified with a solar fence charger and was attached to built-in posts. Each pen contained a low-profile .