Transcription

For Children Birth to Age ThreeIllinois Early LearningGuidelines

ContentsIntroductory Letter & Acknowledgments.vIntroduction.1Development of the Guidelines. 5How to Use the Guidelines. 6The Newborn Period. 8Self-Regulation:Foundation of Development.11Physiological Regulation. 13Emotional Regulation.17Attention Regulation.21Behavior Regulation. 25developmental domain 1:Social & Emotional Development. 29Attachment Relationships. 31Emotional Expression. 35Relationship with Adults. 39Self-Concept. 43Relationship with Peers.47Empathy.51iii

developmental domain 2:Physical Development & Health. 55Logic & Reasoning.113Gross Motor.57Quantity & Numbers. 117Fine Motor.61Science Concepts & Exploration.121Perceptual. 65Safety & Well-Being. 125Self-Care. 69developmental domain 3:Language Development, Communication,& Literacy. 73Approaches to Learning. 129Curiosity & Initiative. 131Problem Solving.135Confidence & Risk-Taking. 139Social Communication. 75Persistence, Effort, & Attentiveness.143Receptive Communication. 79Creativity, Inventiveness, & Imagination.147Expressive Communication. 83Early Literacy.87developmental domain 4:Cognitive Development.91Concept Development. 93Memory. .97Spatial Relationships. 101Symbolic Thought. 105ivCreative Expression. 109AppendicesHorizontal Alignment.Appendices Tab, overleafVertical Alignment. 152Glossary. 154Endnotes. 156

For Children Birth to Age ThreeIllinois Early LearningGuidelinesDear Reader,It is with great pleasure that we present you with the Illinois Early Learning Guidelines for childrenfrom birth to three years of age. These Guidelines are the product of two years of intensive labor bymany individuals and organizations. We have all focused on building comprehensive developmentallearning standards for our youngest learners that form the foundation for all learning and development that is to follow. The myriad stakeholders involved in this project were driven by the followingintentions for the use of the Guidelines:We hope the Guidelines speak to you, putting into words the development you see occurringeach day with children from birth to threeWe hope the Guidelines support you in understanding and discussing child developmentWe hope the Guidelines make you better equipped to plan for intentional interactions withchildren from birth to threeWe hope the Guidelines strengthen your commitment to responsive, developmentally appropriatepractice with young childrenWe hope the Guidelines enhance your belief system around the individual nature of thedevelopmental trajectory and the crucial role that family and context play in each child’sdevelopmentWe have had the honor of guiding a process to develop Early Learning Guidelines for birth to threethat embody an approach that is responsive to our state early childhood infrastructure’s work andcurrent needs in this area. In this project guidance and management role embedded within theIllinois Early Learning Council, we were able to draw out the best of our colleagues and stakeholdersv

Acknowledgmentsin the areas of knowledge, practice, and cross-system strategizing. Through this work we were establishing a shared set of beliefs around what children from birth to three should know and be able todo and what our responsibility is to seeing these outcomes for children. Over the course of the twoyear project term, we asked a lot of everyone involved, and ourselves, and found that a shared commitment to young children drove us to push for the highest quality set of developmental guidelines.Inherent to our definition of quality was the need for this work to cut across all the service systemsand sectors serving children from birth to three and their families. Each of these systems and sectorsThank you to Robert R. McCormick FoundationBoard and staff for their generous support of theproject with a commitment that demonstratesrespect for the process and for the Illinois stakeholders, and, most significantly, a reverence forthe importance of supporting children frombirth to three years. The McCormick Foundation continues to be a valued partner in furthering development of a high quality early learningsystem for our youngest children.has had a hand in the creation of the Early Learning Guidelines with a careful consideration of therole of this content in their work with children and families. We are eager to continue to learn fromone another and support each other in implementing the Guidelines to improve the quality of services delivered to children and families.With our sincerest thanks,viJeanna M. CapitoKaren YarbroughExecutive DirectorDirector, Policy Planning and KnowledgePositive Parenting DuPageOunce of Prevention FundThank you to the Early Learning GuidelinesWorkgroup members for their substantial contribution of time to guide a process that neverlost sight of children from birth to three, andto the Writing Team members for their tirelesscommitment to getting the content just right.Barbara Abel, University of Illinois at ChicagoJennifer Alexander, Metropolitan FamilyServicesVincent Allocco, El ValorCasey Amayun, Positive Parenting DuPageJeanne M. Anderson, Nurse Family Partnership– National OfficeGonzalo Arroyo, Family Focus – AuroraAnita Berry, Advocate Health CareJill Bradley, Illinois Action for ChildrenSharonda Brown, Illinois State Board ofEducation

Ted Burke, Illinois EI TrainingStephanie Bynum, Erikson InstituteJennett D. Caldwell, Peoria Citizens Committeefor Economic Opportunity, Inc.Jill Calkins, Tri-County Opportunities CouncilAlexis Carlisle, Department of Children andFamily ServicesLindsay Cochrane, Robert R. McCormickFoundationKimberly Dadisman, Chapin Hall Center forChildrenKathy Davis, Springfield SD 186Elva DeLuna, Illinois Department of HumanServicesClaire Dunham, Ounce of Prevention FundBridget English, Jacksonville SD 117Mary English, Jacksonville SD 117Jana E. Fleming, Erikson InstituteMary Jane Forney, Illinois Department ofHuman ServicesPhyllis Glink, The Irving Harris FoundationJulia Goldberg, Childcare Network of EvanstonPat Gomez, La Voz LatinaMarsha Hawley, Kendall CollegeTheresa Hawley, Educare of West DuPageLynda Hazen, Head Start DuPageArtishia Hunter, Postive Parenting DuPageJean Jackson, Community Child CareConnection, Inc.Raydeane James, Illinois State Board ofEducationLeslie Janes, Carole Robertson Center forLearningJamilah R. Jor’dan, Jor’dan Consulting Group, Inc.Susan Kaplan, Illinois Association for InfantMental HealthLeslie Katch, National-Louis UniversityJoanne Kelly, Illinois Department of HumanServicesKathy Kern, Parenthesis, Inc.Ashleigh Kirk, Voices for Illinois ChildrenRebecca Klein, Ounce of Prevention Fund –Hayes CenterJon Korfmacher, Erikson InstituteLinda Langosch, Community & EconomicDevelopment Association of Cook CountyRima Malhotra, Chicago Public SchoolsJanet Maruna, Illinois Network of Child CareResource & Referral AgenciesJean Mendoza, Early Childhood and ParentingCollaborativePaulette Mercurius, Chicago Department ofFamily and Support ServicesSusan R. Miller, ConsultantLauri Morrison-Frichtl, Illinois Head StartAssociationHeather Moyer, Teen Parent ConnectionChristina Nation, Parents as Teachers –Springfield School DistrictNara Nayar, Advance IllinoisKristie Norwood, Chicago CommonsSessy Nyman, Illinois Action for ChildrenGregory O’Donnell, Ounce of Prevention FundMarcia Orr, Before and After SchoolEnrichment, Inc.Patricia Perez, City Colleges of ChicagoChristy Poli, Bensenville Birth to ThreeProgramRosaura Realegeno, Family Focus – AuroraSusan Reynolds, Chicago Public SchoolsVanessa Rich, Chicago Department of Familyand Support ServicesKate Ritter, Illinois Action for ChildrenJessica Roberts, Voices for Illinois ChildrenCelena Roldan, Erie Neighborhood HouseJohn Roope, Chaddock Child and Family CenterAllen Rosales, Christopher HouseGina Ruther, Illinois Department of HumanServicesChristine Ryan, Chicago Public SchoolsAndrea Sass, YWCA of Metropolitan ChicagoLinda Saterfield, Illinois Department of HumanServicesJoni Scritchlow, Illinois Network of Child CareResource & Referral AgenciesMary Self, Make A Difference – BradleyElementary School DistrictCherlynn Shelby, Department of Children andFamily ServicesKathleen M. Sheridan, National-LouisUniversityHeather Shull, Early Explorations, Inc.Julie Spielberger, Chapin Hall Center forChildrenLauren Stern, El ValorMary Lee Swiatowiec, Childcare Network ofEvanstonBarbara Terhall, Easter Seals Joliet Region, Inc.Dawn V. Thomas, University of Illinois atUrbana-ChampaignVictoria Thompson, Children’s HomeAssociation of IllinoisMarsha Townsend, Illinois Department ofChildren and Family ServicesSharifa Townsend, Illinois Action for ChildrenMelissa Veljasevic, 4-C: CommunityCoordinateed Child CareRebecca Waterstone, SGA Youth and FamilyServicesvii

Xiaoli Wen, National-Louis UniversityDeb Widenhofer, Baby TALK, Inc.Candace Williams, Positive Parenting DuPageKatie Williams, U.S. Department of Health andHuman ServicesCass Wolfe, Infant Welfare Society of EvanstonJanice Woods, Chicago Commons – New CityTweety Yates, University of Illinois at UrbanaChampaignOver the course of this process, the WorkGroup has relied upon the input and lessonslearned from numerous stakeholders withinIllinois and from peers in other states. Thankyou all for taking the time to guide us withyour extensive feedback during interviews andconversations.A total of 24 interviews were conducted; thankyou to representatives from the following Illinoisentities for their time and expertise:Advocate Healthy Steps for Young ChildrenChicago Department of Family and SupportServicesErikson InstituteIllinois Birth to Three Training InstituteIllinois Chapter of the American Association ofPediatricsIllinois Children’s Mental Health PartnershipviiiIllinois Department of Children and FamilyServices Child Care LicensingIllinois Department of Human Services (IDHS),including the Bureaus of Child Care andDevelopment, Child and Adolescent Health,and Early Intervention; the Head StartCollaboration Office; the Healthy FamiliesProgram; and Migrant and Seasonal Head StartIllinois Early Intervention Training ProgramIllinois Head Start AssociationIllinois Home Visiting Task ForceIllinois Infant Mental Health AssociationIllinois Network of Child Care Resource andReferral AgenciesIIllinois State Board of Education’s EarlyChildhood DivisionKendall CollegeProfessional Development Advisory CouncilWestern Illinois UniversityThank you to the following states, representativesof which participated in in-depth interviews:CaliforniaKentuckyMaineNebraskaNorth CarolinaPennsylvaniaSouth CarolinaWashingtonTo our Illinois state agency partners, thankyou for committing not only to the work of thecreation of ELGs for birth to three but also tothe longer term impact that will come fromthe implementation of this content across allprograms in Illinois.Illinois Department of Child and FamilyServicesIllinois Department of Human ServicesIllinois State Board of EducationProject management from the Ounce ofPrevention and Positive Parenting DuPagethank the following individuals for being partof the team: Samantha Aigner-Treworgy, forproject coordination and staffing; BarbaraDufford, our communications designer;Jessica Rodriguez Duggan, our technical writer;and Catherine Scott Little, national expert onearly learning guidelines and processes tocreate them, for guidance on process designand review of the complete content.

IntroductionChildren’s experiences in thefirst three years of life influencehow they develop, learn, andinteract with their world. Thisperiod is marked by an extraordinary amount of growth,and sets the foundation forchildren’s future learning andongoing development.The Illinois Early Learning Guidelines aredesigned to provide early childhood professionals and policy makers a framework for understanding development through information onwhat children know and should do, and whatdevelopment looks like in everyday instances.These Guidelines also provide suggestions andideas on how to create early experiences thatbenefit all children’s learning and development.The main goal of the Guidelines is to offer earlychildhood professionals a cohesive analysis ofchildren’s development with common expectations and common language.1

Children are actually growing and learning inall areas of development at all times.During the process of developing theseGuidelines, core principles were taken into consideration. All of these principles are integratedinto the Guidelines, providing a comprehensiveand appropriate look at children’s development.The core principles are: Early relationships are most important andcentral to young children’s development. Development occurs across multiple andinterdependent domains, in a simultaneousmanner. Children develop and learn at their ownunique pace and in the context of their family,culture, and community. Play is the most meaningful way childrenlearn and master new skills.RelationshipsEarly learning occurs in the context of relationships. Positive and secure relationships arethe foundation for children’s healthy development in all areas and provide models for futurerelationships they will establish. These nurturing relationships give children the security andsupport they need to confidently explore theirenvironment, attempt new skills, and accomplish tasks. Children who have strong, positive2attachments with important adults in their livesuse these relationships to communicate, guidebehavior, and share emotions and accomplishments. These meaningful interactions andrelationships are essential for children’s development as they help them realize they havea meaningful impact on their world and thepeople around them.Domains of DevelopmentChildren’s development is looked at throughfour core developmental domains: social andemotional, physical, language, and cognitive.Children develop across these four domainsat the same time, with each area of development dependent on growth in all the otherareas. There may be times when children seemto focus on one particular area of development,while having little growth in another area. Forexample, a 12-month-old child who is concentrating on language may not display any interestin walking on his or her own. Then, a few weekslater, the child suddenly starts to walk. Thisis an example of how development flows, andwhile it may seem that they may “stall” at certain times, children are actually growing andlearning in all of the areas at all times.Influences on Development andLearningChildren follow a general continuum as theydevelop, and each child will reach his developmental milestones at his own individual pace, andthrough his own experiences and relationships.Development is influenced by various factors:CultureCulture plays a significant role in how childrendevelop, as it influences families’ practices, beliefs,and values for young children. Goals for children’slearning and development differ across cultures.Therefore, it is important for early childhoodprofessionals to know, recognize, and respondsensitively to the multitude of cultural andlinguistic variations that families and childrenexhibit. In order to support healthy development,it is important to provide culturally appropriateactivities and experiences that are responsive tochildren from diverse backgrounds.

Differences in abilities, language, culture, personality, and experiencesshould not be seen as deficits, but instead, be recognized as the uniquecharacteristics that define who children are.Differences in children’s learningabilitiesChildren have varying developmental abilities and different learning styles that influencewhen and how they reach their developmentalmilestones. All children are unique and thesedifferences are to be taken into considerationwhen caring for them. The structure of thelearning environment should be tailored tovarying abilities, and interactions betweenchildren and caregivers should be meaningfuland appropriate. It is important to encourageacceptance and appreciation of differences inlearning abilities and to partner with caregiversto align individual goals for children.TemperamentTemperament refers to the unique personalitytraits that children are born with. Temperamentinfluences how children respond to the worldaround them, and how others will interact withthem.1 Some children are outgoing and assertive and love to try new things. Other childrenare slower to warm up and need time andsupport from adults to engage in new activities.Adults need to be sensitive to children’s temperament and interact with children in a mannerthat supports their temperament to foster feelings of security and nurturing.Birth orderBirth order can influence children’s personalityand how they relate with their family. Childreneach have their own unique personality traits;yet, birth order may have an impact on howchildren’s personality traits are expressed. Forexample, middle children may be more outgoing and social because they have experienceinteracting with an older sibling. Or, youngestchildren may be more persistent because theymay have to work harder for uninterruptedattention.2 These examples may not be consistent across all children, but it is important tonote that all children have unique personalitiesthat influence how they interact and develop.Birth order also impacts the caregiver’s role andhow they parent and interact with each child.For example, there may be differences in howa caregiver approaches their youngest child,compared to their oldest child, due to increasedconfidence in their parenting skills.Differences in abilities, language, culture,personality, and experiences should not be seenas deficits, but instead, be recognized as theunique characteristics that define who childrenare. The important goal early childhood professionals are tasked with during this age period ishow to best support children’s diverse needs.Toxic StressStress is a common experience for allchildren. While positive and tolerable stress – such as moving to a newneighborhood, or parental separation ordivorce – is all part of healthy development, toxic stress is detrimental to thedeveloping child. Toxic stress includesphysical or emotional abuse, chronicneglect, extreme poverty, constantparental substance abuse, and familyand community violence.3 Toxic stressis attributed to prolonged activationof children’s stress systems, withoutsupport or protection from caregivers.4Extended and repeated exposure tothese stressors disrupts children’s braindevelopment and impacts their overalldevelopment, with the possibility oflifelong negative health issues. However,because the brain is still growing duringthe first three years of life, the effectsof toxic stress can be buffered and evenreversed through supportive and responsive relationships with nurturing adults.53

“Play is the means by which the childdiscovers the world.” – UnknownPlayPlay is often described as “a child’s work”; it iscentral to how children learn and make senseof the world around them. Play is often spontaneous, chosen by the child, and enjoyable. Playconsists of active engagement and has no extrinsic reward.6 It is very important to highlight thatplay does NOT include television watching orgames played on the computer or other technology devices.Children use play to learn about their physical world, themselves, and others. Children useplay to sort out their feelings and explore relationships, events, and rolesthat are meaningful to them.Play changes drastically inthe first three years. Forexample, a six-month-oldplays with an object simplyby touching and mouthingit, an 18-month-old purposefully makes an object move in a certain way,and a 34-month-old uses language and actionswhile playing with an object. This exampledemonstrates howplay becomes morecomplex to match andmeet children’s developing abilities.4Who, me? A professional brain developer?Absolutely! Parenting children is the most important job and one of the most challenging. All caregivers are tasked with developing and shaping the brain of society’s youngestscientists. Brain development in the first three years is extraordinary. While children’sbrains are not fully developed at birth, the early experiences in their lives influence the rapidgrowth and development of their brain. Positive and nurturing interactions and experiencespromote neural connections in the brain, which are essential for healthy development andgrowth.7 Caregivers are not only forming how children think through consistent, nurturing, and responsive care; they are also building the foundation for how children learn andinteract with their world.Who are the professional brain developers? Any person who is responsible forthe care of children!Within the Guidelines, there are varying references to caregivers, familiar others, attachment figures, and primary caregiver(s). All of these people impact children’s brain development. Below is a brief description of each:Caregivers and Primary Caregivers include those who are primarily responsible forthe care of the child. Caregivers can include parents, grandparents, relatives, and childcareproviders.Attachment figures, a term used in the Social and Emotional domain, refer to a few, selectcaregivers with whom children have an attachment relationship. Attachment figures caninclude parents, grandparents, relatives, and childcare providers.Familiar others are people who are a common presence in the life of the child. These mayinclude family members, additional childcare providers, other birth-to-three professionalsworking with the family, family friends, occasional caregivers, and neighbors.Within the Real World Stories and Strategies for Interactions, there are examples andsuggestions for how caregivers can promote healthy brain development in young children.

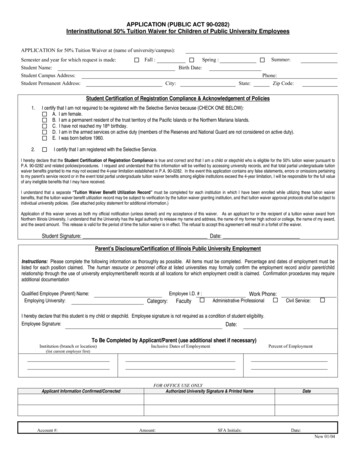

Illinois Early Learning CouncilStructure of collaborationfor the creation of theIllinois Early Learning Guidelines Infant Toddler CommitteeDevelopment of theGuidelinesThe Illinois Early Learning Guidelines weredeveloped in collaboration with key Illinoisstakeholders in the infant-toddler field. Earlychildhood leaders, educators, practitioners,and policy experts came together to ensurethe creation of an accessible and user-friendlydocument, presenting evidence-based and upto-date information on infant-toddler development for parents, caregivers, early childhoodprofessionals, and policy makers. The structureof the group stemmed from the Illinois EarlyLearning Council – Infant Toddler Committee.Within this committee, a Workgroup formed tocreate the vision for the Guidelines. The visionof the group was to ensure a document thatcould align with and integrate into the complexsystem of services for children birth to threein the state, and fulfill the ultimate goals ofimproving program quality, growing providercapacity, and strengthening the current systems. IELG Workgroup3. Develop a more qualified workforce.4. Enhance the current system of early IELG DomainWriting TeamsThe leadership group of the Workgroup thenbegan coordinating the development of theGuidelines, with input from the Workgroupand from the six writing teams, which weresmall sub-groups of the Workgroup. The writing teams were tasked with providing inputand review of developmentally appropriatecontent. This collaborative approach in writingthe Guidelines allowed for important decisionsto be made by a diverse range of professionalsrepresenting different areas of the field. Thiscollaboration resulted in the creation of Guidelines that:1. Create a foundational understandingfor families, providers, and professionals in thefield of what children from birth to age threeare expected to know and do across multipledevelopmental domains.2. Improve the quality of care andlearning through more intentional and appro-priate practices to support development frombirth to three.childhood services by aligning birth-to-three developmental standards with existingstandards and practices for older children andacross system components.5. Serve as a resource for those informingdecision makers involved with developing andimplementing policies for children from birthto three.The Guidelines are NOT intended to replaceany existing resources that are currently used inbirth-to-three programs and are not an exhaustive resource or checklist for children’s development. The Guidelines are NOT a: Curriculum Program model Developmental Screening Tool Developmental Assessment Tool Professional Development CurriculumThe Guidelines are designed to complementthese educational tools and provide a cohesiveanalysis of children’s development with common expectations and common language.5

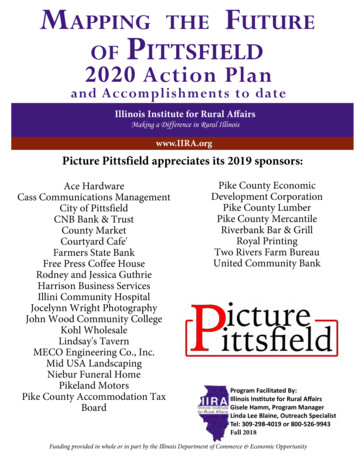

Birth to 9 months7 to 18 months16 to 24 months21 to 36 monthsBirth12 mo.24 mo.Figure 1How to Use theGuidelinesThe Guidelines begin with The NewbornPeriod, which discusses the first four monthsof children’s lives and the experiences that areunique to this time. The first of the six tabbedsections, Self-Regulation: A Foundation ofDevelopment, focuses on children’s development of self-regulation, which is essential foroverall healthy development and learning. SelfRegulation refers to children’s emerging abilityto regulate or control their attention, thoughts,emotions and behaviors.8 Next, Domains ofDevelopment are specific areas of growth anddevelopment. The Guidelines consist of fourdevelopmental domains: Social and EmotionalDevelopment; Language Development, Communication, and Literacy; Physical and MotorDevelopment; and Cognitive Development.The final section, Approaches to Learning,focuses on specific methods by which childrenengage with the world around them in orderto make meaning and build understanding oftheir experiences. These six tabbed sectionsare each structured in the same manner, andare further broken down into Sub-Domains/Sub-Sections, Standards, Age Descriptors,636 mo.Indicators for Children, and Strategies forInteraction.These components map accordingly ontoFigure 2:1 Sub-Domains/Sub-Sections are detailedcomponents of each developmental domain orsection.2 Standards are the general statement of whatchildren should know and be expected to do bythe time they reach 36 months of age.3 Age Descriptors describe the progressionof development for each of four particular agegroups across the birth-to-three age range.These four distinct and overlapping groupsare: Birth to 9 months, 7 to 18 months, 16to 24 months, and 21 to 36 months. Theseage groupings are used in order to reflect children’s bio-behavioral shifts, which are changesin behavior triggered by biological changes inthe brain. These shifts allow children to growand gain new skills (see Figure 1).4 Indicators for Children are some of theobservable skills, behaviors, and knowledgethat children demonstrate to “indicate” progress toward achieving the standard.

Figure 2: Sample spread showing detailed standards represented in the 32 Sub-Sections/Sub-Domains of the guidelines.developmental domain 1: SoCIAl & EMotIonAl DEvEloPME

Casey Amayun, Positive Parenting DuPage Jeanne M. Anderson, Nurse Family Partnership - National Office Gonzalo Arroyo, Family Focus - Aurora Anita Berry, Advocate Health Care Jill Bradley, Illinois Action for Children Sharonda Brown, Illinois State Board of Education in the areas of knowledge, practice, and cross-system strategizing.