Transcription

Master Thesis Business AdministrationFormal institutions and entry modes in developingcountries in Eastern Europe – the case of BulgariaAuthor: Tsvetelina StoyanovaStudent number: s1025007Track: International managementFirst supervisor: Dr. M. L. (Michel) EhrenhardSecond supervisor: R. P. A. (Raymond) LoohuisDate: 15.08.2015

Management summaryThis study concentrates on the relationship between formal institutions and entry modestrategies in Central and Eastern Europe and more specifically it examines the case ofBulgaria. It furthermore seeks to answer the research question: “To what extend doinstitutions enable or constrain the market entry of foreign companies in Bulgaria?” Inorder to do so first a theoretical framework was built. It is based on the most valuedliterature that has been written on this topic. The theoretical framework also suggests somecorrelations between the dependant variable entry mode and the independent one – formalinstitutions. These correlations are later tested by a survey which was developed inparticular for this study.The results from the theoretical framework and the survey are compared and show someinteresting gaps. These are furthermore outlined in details in the discussion part of thismaster thesis. At the end an answer to the research question is proposed as well as someconclusions are drawn. After that the theoretical and practical implications are discussed.At last some limitations of the research are presented together with some ideas for futureresearch.2

Table of contentsChap ter 1: Int roduct ion . 41.1Backg round. 41.2Research question . 51.3Academic and practical relevance . 51.4Outline of the thesis . 5Chap ter 2: Literatu re Rev iew . 72.1 Fo reign entry modes . 72.1.1 Mergers and acquisitions . 72.1.2 Jo int ventures . 92.1.3 Greenfield . 92.2 Institutions and entry modes .122.3 Institutions and entry modes in emerging economies .132.4 Institutional environ ment in Bu lgaria .16Chap ter 3: Methodo logy .183.1 Documentary analysis .183.2 Questionnaire .223.2.1 Measurement .233.2.2 Samp le .233.2.2 Data collection .24Chap ter 4: Research find ings .254.1 Descriptive analysis .254.2 Correlation analysis .264.3 Regression analysis.28Chap ter 5: Ev aluat ion o f the condu cted research .355.1 Conclusion.355.2 Discussion .355.3 Theoretical and practical imp lications .365.3.1 Theoretical implications .365.3.2 Practical implications .365.4 Limitations and future research .37References: .38Internet sources :.41Appendix 1: Questionnaire .42Appendix 2: Correlation matrix.473

Chapter 1: IntroductionBulgaria is a small ex-communist state situated in South-Eastern Europe. It is a member ofthe European Union since 1st January 2007. The country is defined as an emergingeconomy and more specifically as a transition economy. Bulgaria‟s transition from acommunist country into a democratic one involves structural, political and economicreforms. Bulgaria transformed its central planned economy into a market based economy(Hristova Bratoeva-Manoleva, 2010). Currently the country is doing well, however, onlycompared to countries like Greece and Spain. Furthermore accord ing to the GlobalCompetitiveness Report 2013-2014 released by World Economic Forum, Bulgaria provesitself poorly in terms of institutions - 107 rank, goods market efficiency - 81, financialmarket development - 73, business sophistication - 106, and innovation - 105. The reportfurther presents “the most problematic factors for doing business” as regarded by businessexecutives. The results of the World Economic Forum‟s Executive Opinion Survey in 2013show 16 threats to Bulgaria‟s economic development, o f which the first three factorsturned out to be particularly severe, namely corruption, access to financing and inefficientgovernment bureaucracy.This thesis seeks to explore the business environment in Bulgaria and more particularly inwhat way institutions affect the business entry mode choice of foreign companies.1.1 BackgroundInstitutions shape incentives in human interaction – political, social as well as economic.They provide a structure to everyday life and thus reduce uncertainty (North, 1990).Furthermore institutions are expected to reduce transaction and information costs byproving lower uncertainty level and creating a stable structure in order to facilitateinteractions (Hoskisson, 2000). However, it is important to note that institutional contextsin developed countries differ from those in emerging economies (Hoskisson et al, 2000). Akey difference is the existence of market supporting institutions in the first ones and thelack of them to some extent in latter ones (Meyer et al, 2009).Manolova & Yan (2002) argue that the current institutional environment in Bulgaria ishostile, unpredictable and corrupted. Among the key institutional players are law makers,tax collection agencies, and regional authorities issuing various business permits4

(Manolova & Yan, 2002). This master thesis explores the impact of institutionalenvironment in Bulgaria - a developing country in transition - on the business strategies offoreign companies operating in the country. More specifically it concentrates on the entrymode strategy choice. The ways to enter directly a foreign market are, as follows:greenfield, acquisition and joint venture (Meyer et al, 2009).1.2 Research questionThe research question is going to guide this study and will be answered in the co nclusionchapter:To what extend do institutions enable or constrain the market entry of foreign companiesin Bulgaria?1.3 Academic and practical relevanceThis master thesis has value as for the theory as well for the practice. One of the theoreticalimplications of this project is that it examines most of the relevant literature on institutionsand FDI and generalizes the most important aspects by creating new theoretical models.Furthermore these theoretical models could be the basis for a better understanding of theinstitutional environment in one specific country – and namely Bulgaria – and its influenceon FDI. The third implication of this master thesis is the fact that there isn‟t any otherstudy examining in depth the connection between institutions and FDI in this way.The practical relevance of this project is not less important. The results of the conductedresearch will show if there is a gap between literature and practice. In addition to this studycould give some directions about what could be improved in the institutional environmentin Bulgaria. Furthermore the potential investors could obtain some experience andknowledge from the current ones which could ease their future work in Bulgaria.1.4 Outline of the thesisThe first chapter of this thesis gives some general information about the topic, representsthe research question and added value of the project. In order to give an answer to theresearch question 5 more chapters have been elaborated. The second one represents thetheoretical framework for this study. The methodology section (chapter 3) discusses theresearch method that was chosen for this project. In chapter 4 the results from theconducted study are going to be presented. The next section draws some conclusions and5

gives an answer to the research question. The final chapter 6 discusses the limitations ofthis research and gives some propositions for future research.6

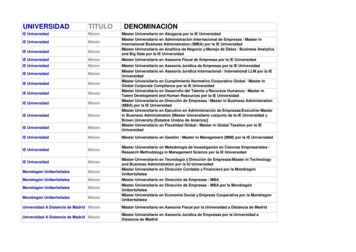

Chapter 2: Literature ReviewIn this chapter the different kinds of foreign entry modes with their advantages anddisadvantages are going to be discussed. As next the relationship between institutions andforeign entry mode choice is going to be investigated or more specifically how the firstinfluences the latter. In the final section of this chapter the institutional environment inBulgaria is going to be examined.2.1 Foreign entry modesCompanies aiming at entering a foreign market can choose from a variety of entry modes(Al-Kaabi et al, 2010). Entry mode strategy is of a significant importance for foreignentrants because it concerns the potential success as well as the probability of survival.This choice has to do with an important decision regarding the degree of ownership of theinvestment (Delios & Beamish, 1999). On the basis of this entry modes could be dividedinto two groups: non-equity based and equity based (Al-Kaabi et al, 2010). By equitybased entry modes the control and resource commitment are much higher in comparison tothe other ones (Hill et al, 1990). Consequently the potential influence of institutions couldbe much bigger. Because of that in this thesis the second equity based entry modes are ofinterest. Meyer et al 2009 discuss three equity modes and namely: greenfield, acquisitionand joint venture. In addition to that the decision how to enter a foreign market consists oftwo important components: first starting a foreign subsidiary from scratch – greenfield - orinvolving in acquisition; second acting alone – choosing to build a wholly ownedsubsidiary or establishing a subsidiary with shared ownership – JV (Dikova &Witteloostuijn, 2007). Al-Kaabi et al (2010) define two similar opportunities whenengaging in FDI depending on the level of equity ownership – namely choosing betweenfull ownership (i.e., a wholly owned subsidiary) or shared ownership (i.e., a JV).Furthermore in this section each of the entry modes is going to be discussed in details.2.1.1 Mergers and acquisitionsFor a long time mergers and acquisitions (M&As) have been a popular strategy fo r acompany expansion. This tendency gained especially high speed in the 1990s (Shimizu etal, 2004). Nevertheless, there is little empirical evidence regarding the company7

performance improvement by means of acquisition entry mode (Brouthers & Dikova,2010).In an acquisition, the foreign company merges or acquires an established entity in anothercountry thus accomplishing an extensive form of participation – 100 % of ownership(Elango & Sambharya, 2004; Al-Kaabi et al, 2010). This means that the acquiring firm hasfull managerial control (Newburry & Zeira, 1997). In comparison to greenfield or JV,acquisitions can be realized much faster and because of this are preferred as entry modewhen time plays an important role (Elango & Sambharya, 2004). This is the case when, forexample, a company wants to enter a certain market quickly in order to secure a firstmover advantage (Newburry & Zeira, 1997).Cross-border M&As give companies the opportunity to access new markets, as well as togain new knowledge and acquire new capabilities (Shimizu et al, 2004). However,acquisitions require full resource commitment right at the beginning of the project(Brouthers & Dikova, 2010).M&As have, however, have a few weak points which have to be considered whenchoosing entry mode strategy. Brouthers & Dikova (2010) state that acquisitions are notalways the best possibility when expanding, especially into international markets. Asstarters acquiring a firm calls forth a couple of challenges in managing the acquiredbusiness (Meyer et al, 2009). More precisely, managers at multinational enterprises(MNEs) of the buying company face the following problem: they have to assimilate theexisting national and organizational culture, and policy (Newburry & Zeira, 1997).Furthermore acquisitions are often in danger of cultural clashes between parent andacquired entities, which impedes knowledge flow (Brouthers & Dikova, 2010). Dikova andWitteloostuijn (2007) endorse this assertion and state that coping and managing the processof overcoming the liability of foreignness could be difficult without a local partner. Inaddition to that there is also a financial risk. The acquiring company has full or near-fullresponsibility for the potential success or failure of the acquired firm (Newburry & Zeira,1997). Moreover acquisitions are expensive and companies make considerable nonreversible (or semi- reversible) resource commitment, which increase the risk by a possiblefailure even more (Brouthers & Dikova, 2010). Shimizu et al 2004 add another weak pointof M&As by arguing that uncertainty and information asymmetry in foreign marketsimpede adjustment and learning from both the local market and the target company(Shimizu et al, 2004).8

2.1.2 Joint ventures“An equity international joint venture is a separate legal organizational entity representingthe partial holdings of two or more parent firms, in which the headquarters of at least one islocated outside the country of operation of the joint venture. This entity is subject to thejoint control of its parent firms, each of which economically and legally independent of theother” (Newburry & Zeira, 1997, p. 89). Elango and Sambharya (2004, p. 110) furthermoredefine joint ventures (JV) as:”a partnership wherein the venture (business) is jointly ownedby two or more firms”. Shared ownership – such as JVs – gives the possibility to share notonly risk, but also strengths, especially local market knowledge of aimed market partner(Al-Kaabi et al, 2010). Kirby & Kaiser 2001 also share this assertion: “JV can be seenprimarily as a device to gain access to resources embedded in other organizations and, [ ]and as a mean of acquiring local management expertise and connections in order tofacilitate fast entry into new markets”. Furthermore this entry mode allows more flexibilityin the sourcing and deployment of resources. This on the other hand facilitates theovercoming of industry barriers and minimization of risks of liabilities of foreignness(Elango and Sambharya, 2004). Another advantage of the JV is that having a local partner“can help firms gain legitimacy because partnering with a local firm can help it createstructures and activities that conform with local norms, va lues and expectations”(Brouthers et al, 2008, p. 193).However JVs is not a perfect entry mode – it hast its disadvantages as well. First of all,having to work with partners makes management and other activities more complicatedbecause there are multiple viewpoints that need to be thought through by formulatingbusiness policies and strategies (Newburry & Zeira, 1997). Dikova & Witteloostuijn(2007) furthermore discuss the difficulties coming from different interests and goals. Incomparison to acquisitions where the investor has access to all resources, in JVs only theresources placed by the local partner are accessible (Meyer et al, 2009).2.1.3 GreenfieldThere are many definitions of the greenfield entry mode. New and Zeira (1997, p. 89)define it as follows:”An international greenfield investment is the establishment of a newaffiliate in a foreign host country by a company headquartered outside the country wherethe investment is occurring for the purpose of producing a company‟s product or providinga company‟s device”. Shimizu et al (2004, p. 311) give another definition:”Greenfield9

ventures involve establishing wholly owned subsidiaries in new geographic markets”.Elango and Sambharya (2004, p. 109) furthermore define greenfield as:”a foreign firmstarts operations on its own in a host country”. As it can be noticed there are two importantcharacteristics of this entry mode, mentioned in all of the above listed definitions: newaffiliate (started from scratch) and taking place in a foreign country.There are several reasons for choosing greenfield as an entry model. First of all, it enablesthe establishment of common organizational culture and thus making knowledge transferfrom the new affiliate to the parent company easier (Brouthers & Dikova, 2010). All of thisis possible because entering a foreign market by means of a greenfield secures theinvesting company full control over the local operations (Dikova & Witteloostuijn, 2007).This is especially important in emerging economies, where property rights protection isweak, because in this way competitive advantage is better protected (Dikova &Witteloostuijn, 2007). Another advantage of the greenfield entry strategy concerns thefinancial part. This kind of entry mode requires “lower upfront investments and henceminimize(s) downside risks” (Brouthers & Dikova, 2010, p. 1049). In addition to thatgreenfields give an opportunity to make bigger investments by favorable conditions orabandonment at considerable lower price when things don‟t turn out as expected(Brouthers & Dikova, 2010).One of the critique points of greenfield ventures is that they have a longer establishmentperiod and need more time in order to build local business networks (Dikova &Witteloostuijn, 2007). Furthermore although they require lower investments, by a potentialfailure the financial exposure is bigger in comparison to JVs, where ownership is divided(Newburry & Zeira, 1997). Another weak point of the greenfield entry mode is theovercoming of liability of foreignness without the support of a local partner (Dikova &Witteloostuijn, 2007).In the table below the advantages and disadvantages of the three entry modes aresummarized.10

Table 1: Entry modes advantages and disadvantagesMode of entryGeneralAdvantagesM&A Merging with oracquiring anestablishedentity in aforeign country An extensiveform ofparticipation(100%ownership) Full managerialcontrol (fullownership) M&As can berealized very fastfirs moveradvantage Access to newmarkets,knowledge andcapabilitiesJoint venture The business isjointly owned bytwo or morefirms Theheadquarters ofat least one islocated outsidethe country ofoperation of thejoint venture Establishing awholly ownedsubsidiary It takes place ina foreigncountry Shared risk More flexibility inthe sourcing anddeployment ofresources Having a localpartner who canhelp in gaininglegitimacyGreenfield Possibility forestablishment ofcommonorganizationalculture Full control overlocal operations Flexibility regardingLong establishmentperiodsize of investmentsDisadvantages Need forassimilation ofthe national andorganizationalculture and policyof the acquiredcompany Danger of culturalclashesknowledge flow isimpeded M&As areexpensive High financial risk( full or near-fullresponsibility) Uncertainty andinformationasymmetryimpedeadjustment andlearning Having a partnercan make theworking processmore complicated Different interestsand goals Only theresources placedby the localpartner areaccessible By potentialfailure financialexposure is biggerOvercoming ofliability of foreignnesswithoutthesupport of localpartner11

2.2 Institutions and entry modesIn this section the relationship between institutions and entry mode choice is going to bediscussed.North (1990, p. 3) define institutions as “the rules of the game in a society or, moreformally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction”. Thisdefinition includes formal institutions – laws and regulations, and informal – customs,norms and cultures (Meyer & Peng, 2005).A new direction of research argues that institutions are nowadays much more than just“background conditions” (Meyer et al, 2009). Researchers have realized that institutionshave significant importance and it is no longer possible for strategy research to concentrateonly on industry conditions and company resources (Peng, 2002). Institutional theory hasturned out to be a strong and useful instrument for analyzing individual and organizationalactions over the time (Dacin et al, 2002). One of the reasons for that growing interest isthat it provides a rich theoretical basis for examination of a wide range of critical problems.Furthermore institutional theory gives an opportunity for theory building at various levelsof analysis, which is of a significant importance for multinational company (MNC)research (Kostova et al, 2008).Dikova and Witteloostuijn 2007 discuss the importance of institutions in terms of degree ofinstitutional advancement – “the extent to which market-economy-consistent rules of thegame are operational” (p. 1015). Formal and informal institutions take part in theinteractions between companies and in this way “affect the relative transaction andcoordination costs of production and innovation” (Meyer et al, 2011, p. 237). Institutionsare furthermore accountable for the transfer of corporate social responsibility (CSiR). Morespecifically the less developed the institutional environment in a host country, the morelikely MNEs will carry over their CSiR practices to the subsidiaries (in the host countries)(Surroca et al, 2013).Institutions have a significant role in a market economy. They have to sustain the effectivefunctioning of the market mechanism. This would make it possible for companies andindividuals to participate in market transactions without causing unwanted costs and risks(Meyer et al, 2009). When markets function without difficulties in developed countries, themarket-supporting institutions cannot be noticed. On the other hand when markets do not12

function properly, like in emerging economies, the absence of stable formal institutions institutionalmodel“organizational survival is determined by the extent of alignment with the institutionalenvironment; hence organizations have to comply with external institutional pressures”(Kostova et al, 2008, p.997). This would explain why institutional differences areespecially important for MNEs operating in various institutional environments (Meyer &Peng, 2005).Another aspect of the institution based- view is that it influences on firms‟ strategic choicesand strategies like, for instance, entry mode (Meyer et al, 2009) and defines the possibilityfor bargaining between investors and authorities (Meyer & Peng, 2005). More specificallyDikova and Witteloostuijn (2007) argue that greater institutional advancement is aperquisite for acquisition establishments. This is thesis is also supported by Meyer andPeng (2005). They state that by less developed formal marketing supporting institutionsMNCs would choose JVs and alliances as opposed to wholly owned subsidiaries as anentry strategy.2.3 Institutions and entry modes in emerging economiesAs already mentioned strategies in transition economies (also considered as emergingeconomies, Hoskisson et al, 2000) considerably differ from those in developed ones.Because of this, they can be only explained by taking into consideration the specificinstitutional environment when making an analysis (Meyer, 2002). Moreover companiesthat manage to adapt to institutional “pressures” have better chances at acquiring scarceresources and surviving on the foreign market (Newman, 2000).“An emerging economy can be defined as a country that satisfies two criteria: a rapid paceof economic development, and government policies favoring economic liberalization andthe adoption of free market-system” (Hoskisson et al, 2000, p. 249).The end of the Communism era (1989) freed a new wave of rapid-growth countries in CEE– transition economies. They were aiming at supporting their market mechanism throughliberalization, stabilization and encouragement of private companies (Hoskisson et al,2000). This in its turn has attracted a huge amount of foreign direct investments (FDI) andtrade (Gelbuda et al, 2008). However, the attention of researchers was only recently drawnto the influence of institutions on economic performance (Pournarakis, 2004).13

When the communist system had fallen institutions were not in the position to reduceuncertainty and manage stable structure to support interactions and thus reduce transactioncosts (Meyer, 2001). Slowly formal institutions were formed. This period of constructionis, however, characterized by various difficulties for the international business: overlappingand contradictory legislation, vacuum with incomplete legal frameworks and blurred socialnorms. In addition to that Western companies entering emerging markets had to cope withhigh transaction costs, corruption and low protection of property rights (Meyer, 2001).Consequently this transition process could be really challenging for MNEs (Gelbuda et al,2008). Brouthers (2002) support this by stating that institutional structure weaknesses suchas legal restriction on ownership could be a cause for entry barriers.Institutions also ensure information about business partners and their potential behavior.This on its turn reduces unwanted information asymmetries, which are often a reason formarket failure. As already mentioned, many emerging economies have weak institutionalenvironment and this could cause informational asymmetries. Because of this companiesrun into difficulties and risks regarding partnerships and thus the y have to invest moreresources in information search (Meyer et al, 2009).Meyer et al (2009, p. 63) classified institutions as: “strong” – “they support the voluntaryexchange underpinning an effective market mechanism - and “weak”- “they fail to ensureeffective markets or even undermine markets”. This is especially important for thecompanies operating internationally because formal institutions define the permissibleentry modes (Meyer et al, 2009). For instance, legal restrictions could limit foreign equityownership (Delios & Beamish, 1999).Hypothesis 1a: (The) Weak formal institutions (in Bulgaria) impede the foreign directinvestment process in the country.O‟Cass et al (2012) furthermore argue that an entry mode decision has an influence on theentire company‟s strategy on a certain market. In countries

Master Thesis Business Administration Formal institutions and entry modes in developing countries in Eastern Europe - the case of Bulgaria Author: Tsvetelina Stoyanova Student number: s1025007 Track: International management First supervisor: Dr. M. L. (Michel) Ehrenhard Second supervisor: R. P. A. (Raymond) Loohuis Date: 15.08.2015