Transcription

COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIESSocial Media, Cyber Battalions,and Political Mobilisation in Ghana*Elena Gadjanova, Gabrielle Lynch, Jason Reifler, and Ghadafi Saibu1*The research for this report was funded by the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) andan impact fund award by the University of Exeter’s College of Social Sciences and InternationalStudies. We are grateful to Mumin Mutaru and the Tamale-based team of IPSOS-Ghana for researchassistance, and to Samantha Bradshaw, the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDDGhana), the Institute for Democratic Governance (IDEG), and the Media Foundation for West Africa(MFWA) for comments and advice on our research instruments. Most of all, we are grateful to allof our research participants for their time, generosity, and insight. For further information on theproject, contact Elena Gadjanova (e.gadjanova@exeter.ac.uk).Elena Gadjanova is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Politics at the University of Exeter, GabrielleLynch is a Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Warwick, Jason Reifler is a Professorof Political Science at the University of Exeter, and Ghadafi Saibu is a Junior Fellow at the BayreuthInternational Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS) and a PhD Candidate at the Universityof Bayreuth, Germany.1NOVEMBER 2019

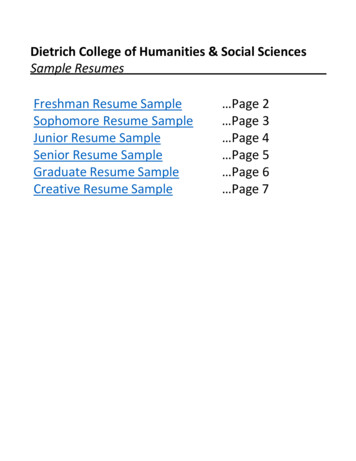

CONTENTSSummary201. Methodology402. Social media influence is greater thannetwork penetration503. Traditional and social media are notseparate spaces704. Social and digital inequalities overlap906. The costs of increased investmentin social media1307. Misinformation is common1408. Some benefits of social media1609. Conclusions1810. Recommendations19“Ultimately, any politician who tries to downplay orunderestimate the influence of social media does soat his own risk, because when things get off on socialmedia, it looks like the proverbial harmattan and dryseason. It is virtually uncontrollable.”Political activist, Tamale, 27 June 2019.05. The big two political parties andthe market for digital entrepreneurs 11SUMMARYThe use and abuse of social media in politics is a subject of increased interest around the world.Social media has attracted much attention both for its capacity to facilitate mass organisation forsocial change, and for its use to spread targeted, divisive, misleading, or overtly false content.This report provides an overview of the mixed impact ofsocial media on politics in Ghana – a country that is oftenheld up as a shining example of democracy in Africa, withits stable party system, closely-fought elections, and regularpeaceful transfers of power. Whether Ghana continues tomaintain this reputation depends in no small part on howsuccessfully the country navigates the challenges to democracyin the digital age.There are many positives to how social media is impacting politicsin the country. Politicians and their supporters are using socialmedia to inform and educate, to organise political meetings andprotests, and to mobilise support. These activities can ensurethat information is distributed more widely, encourage greaterand more informed participation, further boost voter turnout,help to hold leaders to account, empower political activists,and strengthen certain previously marginalised voices.It is clear that social media is playing an increasingly importantrole in Ghanaian electoral politics. Moreover, given the waysin which messages and stories are shared and discussed, itssignificance is far greater than internet penetration figuresalone would suggest. The fact that elections – from partynominations to presidential and parliamentary contests –are often extremely closely fought also means that, while apolitician cannot rely on social media alone, an effective useof platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp can help tomake the difference between winning and losing. Given the(perceived) importance of social media to politics, there isheavy investment in this space.Yet, there are negatives as well. The fact that social mediais generally leveraged to bolster existing campaign strategiesis further exacerbating a number of problems. First, becausethe use of social media is an addition to, rather than areplacement of, older campaign strategies, it is furtherincreasing the cost of (already hugely expensive) campaigns.The added expense only strengthens the position ofwealthy politicians and the two main political parties tothe disadvantage of the less well-off and smaller parties.2Second, because politicians and their supporters tend touse social media to signal status through interactions withconstituents and influential figures, as well as showcasedevelopment activities, this further equates “good leadership”with being (seen as) a “good patron”. While citizens can usesocial media platforms to apply pressure on elected leaders, thefact that such pressure often consists of demands to engage indevelopment projects may only bolster the existing patrimoniallogics of day-to-day politics.Finally, there are other problems that, while not emphasisedby our interviewees at the time of the research, may behidden from view or become matters of concern in the future.Examples include the use of big data to micro-target particulargroups with divisive messaging or misinformation, the employingof spyware to hack ostensibly secure private messaging servicessuch as WhatsApp, and the ability of big business or foreignpowers to use social media to interfere with domestic politicalprocesses and outcomes.At the same time, the use of social media to de-campaignopponents ensures that rumours and misinformation, while farfrom a new phenomenon, can now spread further and morequickly. The ability to use fake accounts and pseudonyms, andthe closed nature of popular WhatsApp groups, also renderssuch problems more difficult to tackle.The first section of this report outlines our methodology.Sections 2 and 3 present a brief overview of social mediause and the relationship between social and traditional mediain Ghana. Section 4 addresses the effect of social media onwidening digital inequalities in the country. Sections 5 and 6delve into the impacts of social media on politics and electoralcampaigns. Section 7 discusses misinformation. Section 8presents a number of positives stemming from expandedsocial media use and gives a number of reasons for cautiousoptimism. Section 9 provides a brief summary and Section 10puts forward a number of policy recommendations drawing onthe findings from the research.The digital age is also creating a new divide between first-handand proxy social media consumers in Ghana, with far-reachingimplications for politics, representation, and social relations.Inequalities in digital access and social media use exacerbatesocio-economic divides in the country and restrict the ability ofsome citizens – most notably rural women – to exercise theirvoice and to engage in politics.3

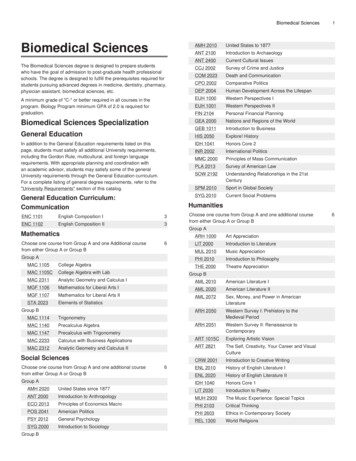

01METHODOLOGYThe analysis presented here draws on the authors’ existing knowledge of Ghana, as well as65 in-depth qualitative interviews and eight focus group discussions with politicians, campaignstrategists, political communicators, political activists, youth group members, journalists andcivil society workers conducted between February and July 2019.The research was carried out in the capital city, Accra, andin Tamale and some of the surrounding areas. The reportalso draws on a custom survey of 1,600 respondents inTamale Central, Tamale North, Tamale South, and Nantonparliamentary constituencies designed by the authors andconducted by IPSOS-Ghana in July 2019. All figures cited inthis report refer to results from that survey.Accra was selected so that the authors could engage withleading figures in the main political parties, civil society andmedia. In Tamale and its surroundings, on the other hand,the authors could study the dynamics of organization andmobilisation on social media in an increasingly competitivepolitical space in a historically-marginalized part of the country.Tamale is Ghana’s third largest city (population 400’000 in2013) and the second fastest growing metropolitan area in234the country.2 It is the capital of the Northern region, which isamong the poorest and least urbanized in Ghana with relativelylimited infrastructure and communication networks, and lowerliteracy rates, particularly among women.302A second-hand smart phone can be bought for as little as GHS 60 (GBP 9 or USD 11) in themarkets of Accra and an increasing number of people around the country are active on socialmedia.4 The most popular platforms are Facebook and WhatsApp, with Instagram a distantthird. Twitter is also gaining ground but is generally regarded as an “elite” platform.Figure 1. Which social media platform(s) do you use?Figure 2. On what device(s) do you access social media?My own mobilephoneIn selecting Tamale and the surrounding constituencies asa case study area, the research has sought to uncover howcitizens engage with social media beyond Ghana’s capital cityand in areas with relatively low digital literacy and internetconnectivity. To our knowledge, no existing studies haveaddressed this question to date. The issue is central to tracingthe impact of growing social media use on politics and socialrelations in the country, and to devising effective measuresto harnessing the positives and tackling the negatives of theexpanding digital space.Fuseini, Issahaka, 2017. “City Profile: Tamale”, Cities 60: 64-74.Ghana Statistical Service, “Urbanisation”, October, 2014, available at essrelease/Urbanisation%20in%20Ghana.pdfSOCIAL MEDIA INFLUENCEIS GREATER THAN NETWORKPENETRATIONMy own computerOn someone else’smobile phoneAt a public computerOn someone else’scomputerOther4Ghana is one of Africa’s largest mobile phone markets with close to 34 million subscriptions and over 10 million active internet users (about athird of the country’s population).5

03Many who use social media check their accounts multipletimes a day and it is not uncommon for people to say thatit is the first thing that they do when they wake up, andthe last thing that they do before they go to sleep. But noteveryone is online. Limited access to wi-fi, the high cost ofdata (1GB of data costs USD 3.60, which is roughly equal totwo per cent of the monthly average income in Ghana),5 andpoor networks across much of the country further reducespeople’s access to, and use of, social media. This is particularlytrue in rural areas.Such limitations notwithstanding, the spread of social media isfar greater than what internet/smartphone penetration levelsalone would suggest. First, those who do have access to socialmedia expose others to online content: young people sharestories that they read with their families; clergy discuss newsin their places of worship; posts and tweets provide a popularsubject for debate in markets and other public spaces. Thisspillover from online to offline social spaces is particularlyimportant given that friends and family are a key source ofnews on politics and current affairs (Figure 3).TRADITIONAL AND SOCIAL MEDIAARE NOT SEPARATE SPACESGiven that the vast majority of stories aired on traditional media in Ghana now originate on socialmedia, no-one is effectively isolated from its reach.This does not mean that social media content reachesthe broader public unfiltered, however. On the contrary,journalists must strike a delicate balance when selectingwhich social media messages to broadcast as they try togain a reputation for “breaking news” while simultaneouslytrying to build and maintain a reputation as reliable andtrustworthy sources of information.Figure 4. Which platform contains the most/least misinformation?Figure 3. Where do you mostly get news on politics?Second, debates on social media help to set the agendaand to also shape the content of traditional media coverage– from print journalism through to TV and radio. Journalistswe spoke to estimated that over 80 per cent of their leads forstories were sourced from social media.56Traditional media sources enjoy relatively high levels of trustin Northern Ghana. Radio and TV are seen as containing theleast amount of misinformation (Figure 4) and are trustedmore than political parties, state institutions, traditionalleaders, and even friends and family (Figure 5). Attention totraditional media appears to be driven precisely by the desireto hear from the “truth arbiters”, but maintaining this statusis treacherous.The journalists we spoke to were keenly aware of the dangersof jeopardizing their reputation and were overall committedto maintaining it. Thus, they were selective of the socialmedia content they discussed, and the manner, in which theydiscussed it. For example, Tamale’s radio hosts were proactivein establishing cross-party WhatsApp groups and policing theirtone and content.Alliance for Affordable Internet, Mobile Broadband Pricing data for 2019, online at: https://a4ai.org/extra/mobile broadband pricing usd2019Q27

Table 1Friends and familyOther communitymembersNDCNPPOther politicalpartiesGovernmentinstitutionsTraditional leaders Religious leadersJournalists andradio 2.9822.6247.3021.7904SOCIAL AND DIGITALINEQUALITIES OVERLAPDigital inequalities matter for political participation, democratic representation,and civic engagement. As politicians, state institutions, and journalists increasinglyseek to engage with citizens on social media, there is a real danger that inequalitiesin data access and social media use will lead to inequalities in voice and representation.Figure 5. How much do you trust informationcoming from the following sources?FriendsandandfamilyfamilyFriendsOther communityOther community membersmembersNDCNDCNPPNPPOther politicalOther po

COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES Social Media, Cyber Battalions, and Political Mobilisation in Ghana* Elena Gadjanova, Gabrielle Lynch, Jason Rei!er, and Ghada" Saibu1 * The research for this report was funded by the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) and