Transcription

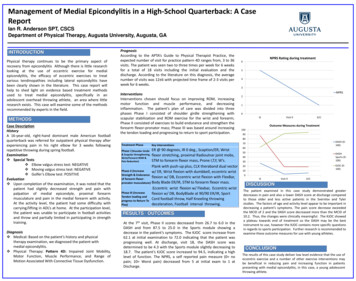

Management of Medial Epicondylitis in a High-School Quarterback: A CaseReportIan R. Anderson SPT, CSCSDepartment of Physical Therapy, Augusta University, Augusta, GAINTRODUCTIONPhysical therapy continues to be the primary aspect ofrecovery from epicondylitis Although there is little researchlooking at the use of eccentric exercise for medialepicondylitis, the efficacy of eccentric exercises to treatvarious tendinopathies including lateral epicondylitis havebeen clearly shown in the literature. This case report willhelp to shed light on evidence based treatment methodsused to treat medial epicondylitis, specifically in anadolescent overhead throwing athlete, an area where littleresearch exists. This case will examine some of the methodsrecommended by experts in the field.METHODSCase DescriptionHistoryA 16-year-old, right-hand dominant male American footballquarterback was referred for outpatient physical therapy afterexperiencing pain in his right elbow for 3 weeks followingrepetitive throwing during spring football.Examination Special Tests Elbow valgus stress test: NEGATIVE Moving valgus stress test: NEGATIVE Golfer’s Elbow test: POSITIVEEvaluation Upon completion of the examination, it was noted that thepatient had slightly decreased strength and pain withpalpation of medial epicondyle, proximal forearmmusculature and pain in the medial forearm with activity.At the activity level, the patient had some difficulty withcarrying/lifting in ADL’s at home. At the participation level,the patient was unable to participate in football activitiesand throw and partially limited in participating in strengthtraining.Diagnosis Medical: Based on the patient’s history and physicaltherapy examination, we diagnosed the patient withmedial epicondylitis. Physical Therapy: Pattern 4D: Impaired Joint Mobility,Motor Function, Muscle Performance, and Range ofMotion Associated With Connective Tissue Dysfunction.PrognosisAccording to the APTA’s Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, theexpected number of visit for practice pattern 4D ranges from, 3 to 36visits. The patient was seen two to three times per week for 6 weeksfor a total of 18 visits including the initial evaluation and thedischarge. According to the literature on this diagnosis, the averagenumber of visits was 12 6 with projected time frame of 2-3 visits perweek for 6 weeks.InterventionsInterventions chosen should focus on improving ROM, increasingmotor function and muscle performance, and decreasinginflammation. The patient’s plan of care was divided into threephases Phase I consisted of shoulder girdle strengthening withscapular stabilization and ROM exercise for the wrist and forearm;Phase II consisted of exercises to build endurance and strengthen theforearm flexor-pronator mass; Phase III was based around increasingthe tendon loading and progressing to return to sport participation.NPRS Rating during treatment6543NPRS210IEVisit 9D/COutcome Measures during Treatment1009080Treatment PhaseKey InterventionsER @ 90 degrees, IR 0 deg., Scaption/ER, Wrist& Scapular Strengthening, flexor stretching, proximal Radioulnar joint mobs,Wrist/Forearm ROM &STM to forearm flexor mass, Prone I,T,Y, W’s.Pain Reduction)Plank with push-up plus, CLX theraband dual vectorPhase II (Increasew/ ER, Wrist flexion with dumbbell, eccentric wristStrength & Enduranceflexion w/ DB, Eccentric wrist flexion with FlexBar,of forearm flexorpronator musculature) Body Blade ER/IR, STM to forearm flexor mass.Eccentric wrist flexion w/ Flexbar, Eccentric wristPhase III (Increaseflexion w/ DB, BodyBlade at 90/90 ER/IR, SportTendon loading andCordfootballthrow,HalfKneelingthrowingprogress to Return Todeceleration, Football interval throwing.Play)Phase I (Shoulder GirdleEcRESULTS / OUTCOMESAt the 7th visit, Phase II scores decreased from 26.7 to 6.0 in theDASH and from 87.5 to 25.0 in the Sports module showing adecrease in the patient’s symptoms. The KJOC score increase from62.1 at initial examination to 72.0 indicating that the patient wasprogressing well. At discharge, visit 18, the DASH score wasdetermined to be 4.3 with the Sports module slightly decreasing to18.7. The patient’s KJOC score increased to 94.5, indicating a highlevel of function. The NPRS, a self reported pain measure (0 nopain; 10 Worst pain) decreased from 5 at initial exam to 1 atDischarge.DASH (0100)706050DASHSports (0100)4030KJOC (0100)20100IEVisit 9D/CDISCUSSIONThe patient examined in this case study demonstrated greaterdecreases in pain and also a lower DASH score at discharge comparedto those older and less active patients in the Svernlov and Tylerstudies. The factors of age and activity level appear to be important indecreasing a patient’s symptoms. The pain score decrease exceededthe MCID of 2 and the DASH score decreased more than the MCID of10.2. Thus, the changes were clinically meaningful. The KJOC showeda plateau towards end of treatment so the DASH may be the bestinstrument to use, however the KJOC contains more specific questionsin regards to sports participation. Further research is recommended toexamine these outcome measures for use with young athletes.CONCLUSIONThe results of this case study deliver low level evidence that the use ofeccentric exercise and a number of other exercise interventions maybe beneficial in reducing pain and increasing function in patientspresenting with medial epicondylitis, in this case, a young adolescentthrowing athlete.

Characteristics of Patients with Adhesive Capsulitis:A Retrospective Case ReviewSara Beth Burch, SPT; Rachel Cozart, SPT; Emily Senger, SPT; Luke Heusel, PT, DPT, OCS; ; Miriam Cortez-Cooper, PT, PhDDepartment of Physical Therapy, Augusta UniversityBackgroundResultsFrozen shoulder, also known as adhesive capsulitis of theshoulder, is a disorder characterized by painful loss of shoulderrange of motion that is not attributed to changes in the cartilage andbone of the shoulder joint. It is thought that the deficiencies inshoulder motion are due to the development of dense adhesions andcapsular thickening of the muscles and tendons of the rotator cuff. 1While a lot is known about the presentation of frozen shoulder, theactual trigger of the disorder is still somewhat of a mystery. Studieshave reviewed the correlation of age, gender, medications, otherconditions (diabetes, thyroid disease), and other factors with theoccurrence of frozen shoulder. Some correlations to these factors arepresent; however there still is no exact mechanism of causation seenacross all cases. A less investigated factor that has the potential toaffect the occurrence of frozen shoulder is menopause. It is knownthat frozen shoulder occurs most often in patients between the agesof 40-60 2 which also happens to be the age range that most womenexperience menopause.3 Therefore, the goal of this current study isto look at characteristics, specifically related to menopausal status,present in patients who present with adhesive capsulitis in order togain insight into the causative factors of this condition.In support of the previous literature, we found thatwomen were more likely to present than men with adhesivecapsulitis. Of our 105 subjects, 73.33% were women. Of thewomen include in our study, 44.16% were between theages of 50-59. The statistical significance of the majority ofour female subjects ranging from 50-59 relates to theprevious study by Juel and Natvig, who noted a peakprevalence of adhesive capsulitis during the same agerange in another cohort study comparing males to females.4Another main finding from our study was found within theanalysis of our subjects’ past medical history. Hypertensionwas the most prevalent diagnosis listed in past medicalhistory for both men and women at 43% and 32%,respectively. A history of having a hysterectomy was thesecond most common past medical history item for womenat 27% followed by diabetes at 17%. Diabetes being fairlyprevalent in the female population, as well as the secondmost common diagnosis for males (39%), was consistentwith the previous literature in regards to the relationshipbetween diabetes and adhesive capsulitis. 5 In regards tomedications taken by our subjects, contrary to our previousresearch, 47% of the females were using some sort ofNSAID at the time of their physical therapy evaluation,followed by 39% who were on some sort of hormonereplacement therapy for various diagnoses. There currentlyis little research investigating the relationship betweenNSAIDs or hormone replacement therapy and adhesivecapsulitis.PurposeTo investigate a potential link between menopausal status and theoccurrence of adhesive capsulitis by analyzing the characteristics ofpatients (men and women) presenting with adhesive capsulitis at alocal physical therapy clinic. We believe we will find similaritiesbetween the patients who have been treated at PEAK RehabilitationClinic for Adhesive Capsulitis that will benefit the future research ofthe underlying physiological cause of this condition.MethodsWe performed a retrospective study of patients (men andwomen) who presented with signs and symptoms consistent withadhesive capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder) at a local physical therapyclinic. To do this, we reviewed physical therapy charts of patientsfrom 2010-2015 at PEAK Rehabilitation Clinic in Augusta, GA andpulled the charts of patient’s with a PT diagnosis of Adhesivecapsulitis. 105 charts were collected and we compared each patient’sspecific characteristics including: age, past medical history,medications, surgical history, duration of symptoms, and length oftreatment to attempt to identify any significant trends. We thenperformed frequency counts and ran several chi-square tests of thecollected data to determine similarities and significant trends amongthese patient characteristics and their diagnosis of This study has several limitations that should be addressed in further research studies.The main limitation is the lack of a control group to compare our 105 subjects to. Byhaving this control group, the researchers could then determine that the trends noticedamong the adhesive capsulitis subjects were not occurring just by chance and are, infact, statistically significant. A second limitation is the lack of reliable past medicalhistory, surgical history, and medication list. All of the information used for this studywas collected from subjective patient report. Therefore, the information collected wouldbe more reliable and valid if the researchers had access to actual patient charts fromtheir primary care physicians rather than using self-report questionnaires. A finallimitation is the lack of information in regards to menopausal status for the femalesubjects. There were no questions on the past medical history form that addressedmenopausal status. Due to this lack of information, the researchers had to makeassumptions on menopausal status based on age, surgical history, and medications.These limitations do not make the results of this study invalid; however, by addressingthese limitations in further research studies it will help to strengthen the conclusionsthat have been made by the researchers.Due to some limitations in the study, no direct link betweenAdhesive Capsulitis and menopausal status was able to bedetermined. However, significant trends found in the datasupport future research regarding the likelihood of thisrelationship. Of the charts analyzed there was a significantlyhigher incidence of adhesive capsulitis in women aged 50-59, afrequent occurrence of hysterectomies, and a common use ofhormone replacement therapy among the women. Futureresearch including a control group, more adequate medicalhistory, and blood sampling should be completed to furtherinvestigate these characteristics and the physiological linkbetween menopausal status and adhesive capsulitis.References:1. Kisner C, Colby LA. The shoulder and shoulder girdle. In: Biblis MM, ed. Therapeutic exercise 6thed. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company 2012:539-610.2. Juel NG, Natvig B. Shoulder diagnoses in secondary care, a one year cohort. BMCMusculoskelet. Disord. 2014;15:89.3. Krailo MD, Pike MC. Estimation of the distribution of age at natural menopause from prevalencedata. Am. J. Epidemiol. Mar 1983;117(3):356-361.4. Juel NG, Natvig B. Shoulder diagnoses in secondary care, a one year cohort. BMCMusculoskelet. Disord. 2014;15:89.5. Milgrom C, Novack V, Weil Y, Jaber S, Radeva-Petrova DR, Finestone A. Risk factors foridiopathic frozen shoulder. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. May 2008;10(5):361-364.

Postural Adaptations to Incline Stance in Subjects with Cerebellar DisorderRaymond Chong, Jen Clark, Nicole Meeks, Katie Sherrod, Taylor SmithDepartment of Physical Therapy, Augusta University, Augusta, GAIntroduction Previous studies have looked at the postural response to standing on anincline to determine an individual’s preferred reference frame for posturalcontrol (Kluzik, Horak, & Peterka, 2005) Upon returning to vertical following 2.5 minutes of 5 toes-up incline stance,healthy subjects exhibited a wide array of postural responses,demonstrating variability among individuals of preferred reference frames(Kluzik, Horak, & Peterka, 2005) The cerebellum influences postural control via the somatosensory branchby receiving proprioceptive information from the limbs and trunk and sendsinformation to the motor cortex to adjust movements. Cerebellar disordermay therefore impede this process and impair postural controlResults (cont’d)Methods (cont’d)Procedure Subjects were informed of the protocol and performed a practice round Participants stood in the NeuroCom (Figure 1) with eyes open for 30seconds on a level surface while baseline force data was obtained Participants were blindfold and a 5 toes-up incline board was placed undertheir feet. They stood in this position for 3 minutes. No data was collectedduring this period After the 3 minute period, the incline board was removed and the subjectthen stood upright for another three minutes, blindfolded, while force datawas collected (Figure 2)Variability of postural sway A/P sway variability during the 30-s quiet baseline stance was similarbetween the groups, 0.2 cm in the Control group versus 0.3 cm in theCerebellar group, p .26 In the post-incline stance phase, subjects in the Cerebellar group showedsignificantly large fluctuations in postural sway (Figure 3) Sway variability was two times higher in the Cerebellar group: 1.1 cmcompared to 0.5 cm in the Control group, p .0295 The purpose of the current study was to determine if cerebellar disorderimpairs the processing of somatosensory inputs for postural orientation,thereby affecting the expression of the lean aftereffects following prolongedstance on an inclineFigure 1Figure 2ResultsEffect of inclined stance on aftereffects Four out of the five subjects in each group displayed the forward leanaftereffects (80% responder rate): χ2 (1) 0.0, p 1.0 The amplitude of sway at the beginning and end of the post-incline stancewas similar between the group: The initial postural lean was 0.25 0.9 cmin the Control group compared to 2 4.3 cm in the Cerebellar group Postural lean at the end was 0.1 0.9 cm in the Control group and 1.3 3cm in the Cerebellar group, p 0.23 in both cases The similarity in postural adaptation also produced a similar range of A/Psway: 1 0.8 cm in the Control group and 1.4 0.6 cm in the Cerebellargroup, p 0.27MethodsSubjectsFigure 3Discussion & Conclusion Inclined stance significantly affected post-inclined stance sway response inthe Cerebellar group The subject who did not show the forward lean had two differentialcharacteristics: an unspecified cerebellar ataxia diagnosis and a relativelyshort disease duration, which may explain the unspecificity These findings support the hypothesis that the presence of a cerebellardiagnosis impairs the processing of somatosensory inputs for posturalcontrol (although adaptation appears to be intact) Areas for further research include: similar testing with subjects groupedaccording to type of cerebellar degeneration and/or disease duration, theintroduction of a visual field during the post-incline stance period to assessthe effect of vision on post-incline lean, and stepping during the inclinephase to assess the impact of muscle and joint receptors on the posturalresponseReferences Kluzik, J., Horak, F., & Peterka, R. (2005). Differences in preferred reference frames for postural orientation shown by after-effects ofstance on an inclined surface. Experimental Brain Research, 162(4), 474-489. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-2124-6 Additionally, 5 age-matched controls (3 M; 2 F) participated in the study,Their mean age was 49 /- 14

Balance and Postural Control Responses to Platform Perturbationsin Cerebellar Degeneration with Light Touch InterventionMary-Alice McBurney, Alexa Sarmir, Austin Shelnutt, Kelly Young, Raymond ChongDepartment of Physical Therapy, Augusta University, Augusta, GeorgiaIntroductionMethods In cerebellar degeneration, the cerebellum progressivelyshrinks and becomes less able to perform the necessaryregulatory processes for which it is responsible Previous studies have found that subjects with cerebellardysfunction have continuous and marked hypermetricresponses in postural gain This study looked at reactive balance both with and withoutthe use of a light touch intervention to examine thecerebellum’s role and the effects of proprioceptive inputsfrom the body in gain control of postural responses to bodydisplacement Postural gain from the tibialis anterior and gastrocnemiusmuscles are examined following platform perturbations, asthey are typically first to respond to platform perturbationsand are easily measured Our hypothesis is that light touch (as a form ofsomatosensory augmentation) will not be effective inimproving balance and postural control responses toplatform perturbations in those with cerebellar disordersParticipantsCommon Procedures Subjects with cerebellar disorder: 5 (4 M, 1 F) Control (healthy) subjects: 5 (3 M, 2 F); Average age 49 yrIDAge(yr)124250352452555Mean 4117116210.51110.5SCA-3Ataxia (unknown etiology)SCA-2Cerebellar degenerationCerebellar degeneration Standing in NeuroCom attached to a harness Tape placed at posterior and lateral bordersof feet 7 large backward translations 7 fast, 8 degree toes up rotationsExperimental (Light Touch) Condition Subject placed right hand lightly touchingwalker with finger tips (Figure 1)Figure 2. No-Touchcondition subjectpositioned insideNeuroCom withhand resting abovewalkerEMG Surface Electrodes Right medial gastrocnemiusRight tibialis anteriorRight forearm flexorsRight forearm extensorsFigure 1. Hand positionFigure 3. LightTouch conditionsubject positionedinside NeuroComwith finger tipslightly touchingwalker (Figure 1)ResultsConclusion In the No-Touch condition, onset latency was 130 18 ms in the Control group and205 64 ms in the Cerebellar group, p 0.06. Onset latency in the Touch conditionwas 132 12 ms in the Control group and 197 59 ms in the Cerebellar group, p 0.04 Mixed model ANOVA revealed an interaction effect between Group andPerturbation, F (7, 56) 2.29, p 0.041, showing an association between thecerebellar group and initial TA muscle response in the toes-up rotationo Initial TA muscle response to the toes-up rotation was excessive in the cerebellargroup: 695% more than the no-touch trial compared to 111% in the controlgroup, p 0.01. The amplitudes of the TA muscle responses remained high inthe next two trials before settling down in the last four trials, p 0.05 (Figure 4) Variability in TA muscle response was observed in onset latency and amplitude ofresponse during toes-up rotation (Figure 5)o Variability in TA onset latency was similar between the Cerebellar and Controlgroups in the No-Touch condition, averaging 11 ms and 14 ms, respectively. Inthe No-Touch condition, TA onset latency in the Control group decreased to 9 msand remained 15 ms in the Cerebellar group, p 0.003o Variability in TA response amplitude in the No-Touch condition differed betweenthe groups, with the Control group at 3 V.s compared to the Cerebellar group at5 V.s, p 0.02. In the Touch condition, variability in response amplitude wascomparable between the groups with an average of 4 V.s Figure 6 illustrates the hypermetric EMG responses and greater variability ofmuscle responses in a cerebellar subject (average of seven trials) Physical therapists should continue to use gaittraining interventions, assistive device trainingand education, balance retraining, vestibularinterventions, visual cues, and functionaltraining programs for task adaptation andfunctional training Subject’s with cerebellar disordersdemonstrated hypermetric responses toplatform perturbations with greater variability inonset latency and response amplitude whencompared to control subjects The hypermetric responses of subjects withcerebellar disorder found in our study indicatethat the cerebellum is involved in modulatingpostural gain in response to platformperturbations, more specifically in tuning downmuscle responses These results support the hypothesis that lighttouch as a form of somatosensoryaugmentation is not effective in decreasing thevariability of onset latency and responseamplitude in subject’s with cerebellar disordersFigure 4. Effect of light touch onresponse amplitudeFigure 5. Variability of muscleresponses in toes-up platform rotationFigure 6. Example of TA EMG activities during toes-up platform rotations

Background DiscussionResultsMultiple Sclerosis is a neurological disease that can resultin deficits in motor, sensory, visual, and cognitivefunctions, skills which are needed for both balance anddriving.These deficits may lead to increased falls and decreaseddriving ability. The data exposes similar deficits that result in increasedfall risk and decreased fitness to drive in people with MS. These deficits cover domains of cognitive processingspeed, visuospatial perception, divided attention task,cognitive inhibition, and memory and processing speed. Overall weaker correlations between cognitive functionand falls risk, likely due to increased motor involvement.Objective LimitationsTo investigate commonalities in motor, sensory, visual,and cognitive deficits in order to later develop a trainingprogram that will benefit both balance and fitness to drive. Methods Prospective cross-sectional design Additionally, a balance assessment and a drivingassessment were performed. The study included 10 ParticipantsLimitations of this study include: small sample size andthe large quantity of correlational analysis’ performed.Graph 1: Correlation Between Driving Abilityand Falls RiskEach participant was scored using series of assessmentsto test their motor, visual, and cognitive functions.The results of these assessments were to analyzed todetermine correlations.Conclusions If future studies validate these cognitive commonalities arehabilitation program could be developed that targetsboth falls risk and driving ability A rehabilitation program should additionally include:training targeted at improving specific cognitive deficitsrelated to either fall prevention or driving improvement.Table 1: Cognitive Commonalities between Driving Abilityand Falls RiskResources andAcknowledgements1. Reference place holder if neededFigure 1: Physiological Profile Assessment: 5 testsTable 2 and 3: Correlation of Cognitive Variablesand Fitness to Drive or Falls RiskThis poster design is adapted from “Allgood M, Pilcher M, Stout A, Threeths J, Cortez-Cooper M. Alter-G Training Following a Total KneeReplacement” located at rch.html.

Effect of Niacin Supplementation on Sleep Function in Parkinson’s PatientsRaymond Chong, Chandramohan Wakade, Banabihari Giri, Jon EidmanAugusta UniversityConclusionIntroductionFigure 1ResultsTotal Sleep380.00The average values for pre and post test scores of each groupwere compared for significant differences using a two-tailed ttest. Total sleep, sleep quality as indicated by time in deep sleep,and sleep latency were compared before and after 3 monthssupplementation. Both the placebo and 100mg niacin groupsexhibited no statistical change in any category while the 250mgniacin groups showed signs of a slight deterioration in sleepfunction as measured by total sleep and time spent in deep sleepfollowing the trial period.360.00340.00320.00Time in MinutesParkinson’s Disease (PD) is an age-related neurodegenerativedisease affecting about 1% of the world population over 65. Growingresearch regarding progression of Parkinson’s Disease suggestsniacin supplementation may offer neuroprotection and positiveeffects on both motor and non-motor symptoms.1 Recent studiesconcluded individuals with Parkinson’s disease exhibit a poorerniacin index and poorer quality sleep when compared to agematched controls, and that niacin supplementation served tonormalize these levels.2 One case control study reports niacinsupplementation was associated with improvements on the UPDRS,PDQ8 quality of life questionnaire, PD sleep scale questionnaire andquality of sleep as measured by Rapid Eye MovementElectroencephalography (REM EEG).3 In this study we evaluate theeffect of niacin supplementation on sleep function as measured byREM EEG in Parkinson’s Disease 0240.00200.00PREPOST100mg Niacin324.69 310.56250mg NiacinTime Spent in Deep Sleep454035Time in MinutesFollowing approval from the Institutional Review Board ofGeorgia Regents University, we began a study involving 45 subjectsrandomly assigned into 3 groups. 15 subjects were assigned to thegroup receiving a dosage, 250mg of slow release niacin. A secondgroup of 14 subjects were assigned to the group receiving 100mg ofniacin, and a third group of subjects containing 16 individualsreceived a placebo. All participants were individuals diagnosed withidiopathic PD. Differences between the groups including age,severity of disease and length of time following diagnosis were notstatistically significant preceding the treatment period. Sleepfunction was evaluated using the Zeo portable EEG headset (fig. 1).Total sleep, sleep quality as indicated by time in deep sleep, andsleep latency were compared before and after 3 monthssupplementation.220.0030*Further studies are warranted to understand the association ofniacin with sleep function in Parkinson’s Disease. Placebo effectand difficulties in maintaining blinding throughout the study dueto a flushing effect, a commonly experienced side-effect ofniacin, may have confounded results. In an effort to avoid thiseffect in the 250mg niacin supplement, a slow release table wasused which may have reduced its efficacy. This result mayindicate that a large dosage administered in a short amount oftime may be necessary to increase the mass effect of niacin onGPR109A and decarboxylase inhibitors.252015PREPOST100mg NiacinResultsPlacebo250mg NiacinReferences1. Wakade C, Chong R. A novel treatment target for Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurological Sciences. Oct 23 2014;347(1-2):34-38.2. Wakade, C., Chong, R., Bradley, E., Thomas, B., & Morgan, J. (2014). Upregulation of GPR109A in Parkinson's disease. PloS One, 9(10),e109818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.01098183. Wakade C, Chong R, Bradley E, Morgan J. Low-dose niacin supplementation modulates GPR109A, niacin index and ameliorates PDsymptoms without side effects. 2015.Average Time to Fall AsleepTotal SleepGroup Name250mg Niacin100mg NiacinPre-test (min.)340 90337 126Post-test (min.)289 101353 102p valuep .017*p .260Placebo325 79311 88p .197504540Total Deep SleepGroup Name250mg Niacin100mg NiacinPre-test (min.)42 3138 31Post-test (min.)28 2135 31p valuep .020*p .672Placebo39 3237 33p .290Time in Minutes3530252015Avg. Time to SleepGroup Name250mg Niacin100mg NiacinPlaceboPre-test (min.)25 2522 1423 15Post-test (min.)45 6915 1817 12p valuep .120**p .228p .164* Indicates significance** Indicates near significance1050100mg NiacinPREPlacebo250mgNiacinPOST

AlterGThe Use of theAnti-Gravity Treadmill to Promote IndependentWalking after Stroke: A Pilot Randomized Controlled TrialLina DahmanJonathan GarrettFaculty Mentor: Charlotte Chatto, PT, PhDDepartment of Physical Therapy, Augusta University, Augusta, GAAbstractClassificationsMedical HistorySubject 1Left-sided CVATime sinceMethods4 monthsSubject 2Right-sidedhemorrhagicCVA6 months7580diagnosisAgeMaleGengerProtocolWill BalanceBoardFemaleAlterGSubject 1 completed an AlterG walking protocol andsubject 2 completed Wii training using the WiiBalance Board. Both subjects completed 30-minutesessions 3x a week for 3 weeks. Each trainingsession for the AlterG followed the same format whichincluded 2 bouts in each of the categories, whichfocused on endurance, independent walking, andspeed. Subject 2 completed a variety of Wii-Fit gamesincluding focusing on balance, stability, flexibility, andstrength and endurance. The subject was progressedby changing position from sitting tostanding, increasing thenumber of repetitionsOutcomeSubject 1performed, and narrowingMeasuresthe base of support.PreFunctional Outcome MeasuresBody Structure/FunctionLimitations Berg Balance ScaleFunctional Ambulation CategoryMini-Mental State ExamRivermead Motor AssessmentGross FunctionRivermead Motor AssessmentTrunk and LegTrunk Impairment Scale.ResultsSubject 6s10.63s-0.97s6MWT122 ft 7inches128ft 5.3ft1210 ft 1inch1212 ft 7inches 2 ft 0.239m/s)*ConclusionsTimed Up and Go Test10.63ActivityLimitations Functional IndependenceMeasureActivities-Specific BalanceConfidenc

recovery from epicondylitis Although there is little research looking at the use of eccentric exercise for medial epicondylitis, the efficacy of eccentric exercises to treat various tendinopathies including lateral epicondylitis have been clearly shown in the literature. This case report will help to shed light on evidence based treatment methods