Transcription

The New Bank-Thrift Competition:Will It Affect Bank Acquisitionand Merger Analysis?MICHAEL E. TREBINGHE Depository Institutions Deregulation andMonetary Control Act (MCA) enacted by Congressin March 1930 will significantly affect the competitiveenvironment in which financial institutions operate.This act broadens both the asset and liability powersof savings and loan associations (S&Ls), mutual savings banks and credit unions, opening opportunities forthese institutions that traditionally have been limitedto banks. In light of these new powers and the increasing erosion of both legal and economic differences between thrift institutions and banking organizations, thrifts have become important competitors inmarkets for banking servicesespecially for transaction or checking accounts.1 Logically, the presenceof thrift institutions should carry greater weight inanalysis of mergers between commercial banks andacquisitions of banks by bank holding companies(BHCs).cial innovations and the geographic expansion of socalled “non-banking” institutions.2 The MCA, in response to these developments, reduces even furtherthe actual differences between banks and thrifts, Regulations that have attempted to control or constrainpricing and portfolio decisions of financial institutionsare being liberalized, In essence, the act provides fora greater reliance on market forces to determine boththe flow of deposits to financial institutions and theflow of credit from these institutions to borrowers. Themajor elements of the MCA that will affect bankthrift competition are listed in table 1. —The following discussion reviews several provisionsof the MCA that permit more intense bank-thrift competition, describes the current approach used by banking regulatory agencies to review applications forapproval of bank mergers and BHC acquisitions,and discusses its validity in light of the new legislation. Finally, the article discusses some alternativeapproaches to the analysis of competition in localmarkets.THE MCAPROVISIONSThe distinctions between thrifts and banks have become less rigid because of a long list of recent finantThe term “thrift institutions” ia this article is defined as sayings and loan associations, credit unions and mutual savingsbanks.An important change is the authorization of interestearning “transaction” accounts at both banks andthrifts. This is achieved through the nationwide legalization of negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW)accounts, automatic transfer service (ATS) accountsand credit union share drafts.4 In some areas of thecountry (especially New England), depository in2See Jean M. Lovati, “The Growing Similarity Among FinancialInstitutions,” this Review (October 1977), pp. 2-11, andHarold C. Nathan, “Nonhank Organizations and the McFadden Act,” Journal of Bank Research (Summer 1980), pp.80-86.3For a more detailed discussion of the elements of the MCAsee “The Depository Institutions Deregulation and clonetaryControl Act of 1980,” Federal Reserve Bulletin (June 1980),pp. 444-53. ATS and NOW accounts represent a type of individual “checking” account. By providing for the automatic transfer of fundsfrom a savings account to cover checks drawn against a zerobalance ATS account, individuals can earn interest on “checking” balances. NOW accounts are interest-eaming savingsaccounts against which customers call write “negotiabledrafts.” Similarly, credit union share drafts permit payabledrafts drawn on a credit union member’s interest-earningshare account. Share drafts, which resemble checks, are processed through the credit union’s account at a commercialbank.3

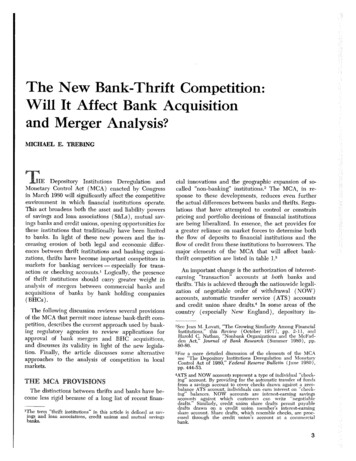

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUISTable 1Selected Provisions from the DepositoryInstitutions Deregulation and MonetaryControl Act of 19801. The phase-out of interest rate ceilings on deposits overa six-year period2. The authorization to ofler NOW (negotiable order olwithdrawaI accounts (fundamentally. interest-earningchecking accounts at all federally insured depository,nstilulions beginning December 31, 1980 to individualsand rion-profi: organizations3. The authorization o share drafts at federally insuredcredit unions (effective March 31, 1980)4. The authorizalior for mutual savings banks to o’ferdemand deposi1s to business customers5. Increased investment oplons for thrift insttulionsFor federal-chartered savings and loans:a. consumer lending commercial paper, anddebt security investment of up to 20 percent of asselsb. issuance of credit cardsc. trust-fiduciary powersFor federal:y insured credit unions:a. real eslaie loansFor federal mulual savings banks.a. commercial, corporate and business loans.(up to 5 percent of assets)stitutions had already offered interest-earning transaction accounts since the early l970s. Accompanyingthese powers is the provision for the gradual phaseout of deposit interest rate ceilings.In addition to these significant changes, the MCAallows S&Ls to engage in consumer lending, trustactivities and credit card operations. The MCA authorizes thrifts to invest in, sell, or hold commercialpaper and corporate debt securities (up to 20 percentof assets). Limited business and commercial loanpowers have also been granted to federally charteredmutual savings banks.The basic findings of the act are that the existinginstitutional structure has discouraged persons fromsaving, created inequities for depositors, impeded theability of depository institutions to compete for fundsand failed to achieve an even flow of funds amonginstitutions. The act also states that all depositors areentitled to receive a market rate of return on theirsavings.4FEBRUARY 1981Credit market activity of thrifts over the pastdecade has developed by piecemeal expansion; theseinstitutions evolved originally as special-purpose institutions whose asset-liability powers have been extended only by gaining legislative approval.5 Legislation in the 1970s has increasingly widened theirpowers and scope of business. The new powers legalized in the MGA will affect further the traditionallines of business that have separated these institutions;banks and thrifts will now compete more directly formany lines of business.CURRENT METHOD OF ANALYZINGCOMPETITIONThe Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 requiresthe Federal Reserve to consider the likely effects ofproposed holding company formations and acquisitionson competition, the convenience and needs of thecommunities involved, and the financial and managerial resources and future prospects of the institulions involved.6 If the Board of Governors finds thata transaction will substantially lessen competition (ortend to create a monopoly or be in restraint of trade),the Board must deny the application unless the anticompetitive effects are judged to be clearly outweighedby “the convenience and needs of the community.”Legal DoctrineThe critical problem in antitrust law is selectingthe specific industry and industry output (or ‘ line ofcommerce”) to use in analyzing competition betweenfirms. In analyzing cases under the Bank HoldingCompany Act, the Federal Reserve has generallychosen “commercial banking” to be the relevant lineof commerce. This definition is based on the SupremeCourt’s controversial Philadelphia National Bank decision in 1963. In this case, the Court concluded that commercialbanks have an advantage over other financial institutions in attracting funds for loans and other services5See Leonard Lapidus, “Commercial Banks and Thrift Institutions: The Differing Portfolio Powers,” Banking Law fournol(May 1975), pp. 450-93, and Jean M, Lovati, “The Changing Competition Between Commercial Banks and Thrift Institutions for Deposits,” this Review (July 1975), pp. 2-8. Competitive analysis is also done with respect to applicationsfiled under the Change in Bank Control Act of 19,8 andmergers filed under the Bank Merger Act of 1960. United States v. Philadelphia National Bank, 374 U.S. 321(1963). Subsequent Supreme Court cases have upheld thisdecision. See United States v. Phillipshurg National Bank andTrust Co., 399 U.S. 350 (1970); and United States v. Connecticut National Bank, 418 U.S. 655 (1974).

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUISsince only they can legally accept demand deposits.In addition, banks were said to enjoy “settled consumer preferences” for full-service banking. Thus, the“general store” nature of the banking business madeit a distinct line of commerce, distinguishing banksfrom other financial institutions.Banking agencies have relied on simple marketshare tests to judge the likely effects of mergers orBHC acquisitions on competition, using “concentration ratios” as a form of prima facie evidence of theseeffects on competition. A concentration ratio is a summary measure intended to represent the degree ofmarket power that larger firms possess.8 This ratio isdefined as the percentage of total industry activity(measured by output, employment, assets, etc.) accounted for by the larger firms. A four-firm concentration ratio (using total deposits as a proxy foroutput) for all the commercial banks in a local banking market, for example, may be 75 percent; that is,the four largest banks hold 75 percent of the totalbank deposits in this market. Although other factors are analyzed in evaluatingthe competitive effects of mergers and acquisitions,concentration ratios continue to be the main factors insuch analysis.’ The important issue is that the calculation of concentration ratios using commercial bankorganization deposit data alone accepts the Court’s5For a discussion of concentration measures used in analysisof banking markets, see “Measures of Banking Structure andCompetition,” Federal Reserve Bulletin (Septeniher 1965),pp. 1212-22.‘See the appendix for a discussion of how the relevant geographic market is defined.10This point is highlighted by the merger guidelines publishedby the Justice Department in 1968 which are frequentlycited in bank merger and acquisition analysis. These guidelines indicate that the department will challenge a horizontal merger between firms in a concentrated industry (i.e.,one with a four-firm concentration ratio greater than 75 )when the following market shares are involved:AcquiringAcquiredFirmFirm4%4% or more10%2% or15%1% or moreIn nonconcentrated markets (i.e. ones with four-firm concentration ratios less than 75%) the Justice Department aba’lenges mergers with the following %4%3%2%1%Merger Cuidelines, U.S. Department of Justice, May 30,1968.FEBRUARY 1981line of commerce definition and assumes that the aggregate of the many products and services suppliedby banks represents a meaningful product line foranalysis of market competition.’1Economic Analysis of Line of CommerceDefinitionThe definition adopted by the Court in 1963 wasbased on a particular view of the market for bankservices: namely, that many bank products are demanded jointly. In other words, it is possible toidentify “clusters” or “bundles” of services demandedby customers for which banks compete.’2 Such demand may result because of transportation costs andtransaction costs (including the cost of obtaining information) which makes it costly or impractical forcustomers to deal with more than one institution.Banks, however, compete in many different productmarkets and in different geographic market areas.Commercial banks participate principally in marketsfor financial assets. Banks demand customer depositswhich they invest in a variety of earning assets. Customers using demand accounts are, in turn, supplieda transaction service. Customers holding time depositsare provided an intermediation service funds areinvested in interest-earning assets, Banks also supplyvarious types of credit, trust services, safe depositservices, correspondent services, etc. Each of theseactivities can be identified as an individual “output”of a bank. One can argue that each “output” is sold in—11The use of such concentration ratios is not necessarily ad hoc.Their use has both theoretical and empirical support in theliterature. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to conclude that theuse of such ratios, essentially a result of data scarcity, hasunfortunately guided research efforts as well. For a summaryof the empirical evidence for banking, see Stephen A.Rhoades, Structure and Performance Studies in Banking: ASvmmary and Evaluation, Staff Economic Studies 92 (Boardof Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 1977) andGeorge J. Benston, “The Optimal Banking Structure: Theoryand Evidence,” Journal of Bank Research (Winter 1973),pp. 220-37. For a criticism of such “conduct/structure/performance” studies, see Yale Brozen, “Concentration andProfits: Does Concentration Matter?” The Antitrust Bulletin(Summer 1974), pp. 381-99. See also Harold Demsetz, “Industry Structure, Market Rivalry, and Public Policy,” Journalof Law and Economics (April 1973), pp. 1-9.i2 4 alternativeargument holds that banks have offereddiverse services in the past because they have been prohibited from paying interest on demand deposits since 1933.Customers holding large demand deposit balances receive“implicit interest” in the form of other services offered belowcost to depositors. In other words, competition resulted ininstitutions, faced with prohibition on direct payment ofinterest, offering implicit interest in the form of services,such as low or zero service charges, drive-in facilities,branches, and occasionally gifts (porcelain china, silverwareand calculators, for example).5

FEBRUARY 1981FEDERAL RESERVE SANK OF ST. LOUISa distinct market defined in terms of specific groups ofbuyers (for example, by location of customer, or maturity and denomination of the particular loan). Therefore, choosing the appropriate measure of bank “output” is a difficult task.’3The above reasoning suggests that the usefulness ofthe line of commerce definition adopted in the Philadelphia case should be determined on empiricalgrounds. Although the “department store” or “clusterof ser

The distinctions between thrifts and banks have be-come less rigid because of a long list of recent finan-t The term “thrift institutions” ia this article is defined as say-ings and loan associations, credit unions and mutual savings banks. cial innovations and the geographic expansion of so-called “non-banking” institutions. 2 The MCA, in re-