Transcription

Original article: Child Abuse in JapanChildAbuse in JapanDavid GoughFew cases of child abuse are identified by child care agencies in Japan. Someargue that this is because the culturally specific child care and family relations inJapan make child maltreatment less likely to OCCUK On the other hand, there arealso cultural features that might act to increase the likelihood of child abuse.Explanations for seeming differences in prevalence are discussed, along with aconsideration of differences in concepts of appropriate care, child maltreatment,thresholds for case definition, and levels of public and professional awarenessabout chiid abuse. Service responses and current developments in child abuse inJapan are also briefly reviewed.Keywords: Japan; child abuse; cross cultural comparison; definitions of maltreatmentlntroductionThroughout history children in many cultures have beenseen as expendable or as a possession that could be tradedfor profit. Japan is no exception to this. Infanticide was acommon form of population control amongst the poor inthe Edo period (1603-1867) and was called ‘Mabiki’ an agricultural term for ‘thinning out’ (Ikeda, 1995). Thispartly explains why the population remained stable at 25million from the mid 17th to mid 19th century beforeclimbing to the current population of 120 million (Kouno&Johnson. 1995).Human trafficking was outlawed in 1872 after the Meijirestoration. but both infanticide and the sale of childrencontinued up into the 20th century and to after the 1933Child Abuse Prevention Act (Ikeda, 1995). After theintroduction of the new constitution in 1947, a number offurther human rights and child welfare laws wereintroduced with the government undertaking surveys onthe circumstances of children in society including knowncases of child abuse. Recently there have been a numberof further surveys of known cases of abuse (see Table 1).David GoughAssociate Professor,Japan Women 5University, 1 - 1 - 1Nishiikura, Tarna-ku,Kawasaki-shi, Japan214The reccnt medical and social welfare literature on childabuse began in the late 1970s following on from the rediscovery of child abuse in the United States (Ikeda,1979). Since that time there has been an increasingnumber of publications about abuse in both the public andprofessional media. From an initial focusing on physicalabuse and neglect, more work is appearing on sexualabuse. Recent research includes Ikeda and Satoh’s (1992)survey reporting that at least 73% of students had receivedunwanted sexual experiences in childhood (mostly onpublic transport by male molesters known as ‘chikan’)and Takii’s (1992) finding that 5.4% of residents at acorrectional home for young women had been victims ofsexual abuse by male relatives or maternal boyfriends.Recent books include an edited collection about knowncases of sexual abuse (Kitayama, 1994) and a personalaccount of surviving sexual abuse (Hozumi, 1994). Childabuse has also been presented in ‘manga’ comics andnovels such as ‘Fatherfucker’ (Uchida, 1993), the largelyautobiographical story of a young woman abused by herstep father, and the more sensational ‘Coin LockerBabies’ (Murakami, 1980), where two boys abandoned atbirth in left luggage lockers make it their life mission toseek vengeance against their mothers.English language books translated into Japanese includethe Open University Course set book (Stainton Rogers,Heliey & Ash, 1989), a medical guide to the recognitionof abuse (Rose, 1985), the Maria Colwell Report(Department of Health and Security, 1974) and‘Understanding Child Abuse’ (Jones et al., 1987). TheCourage to Heal (Bass & Davis, 1988) is currently beingtranslated.Despite the increased discussion about child abuse andsome practice developments by special interest groups,the reported incidence of child abuse by child guidancecentres is low, at about 0.07 cases per thousand children(based on 2,000 cases per year as reported by Directors ofPublic Child Guidance Centres, 1989), much less than the3 per thousand cases on many UK child protectionregisters (Department of Health, 1993). This difference inincidence is central to any discussion of child abuse inJapan as it affects the extent that child abuse is consideredan important social issue requiring society’s attention.

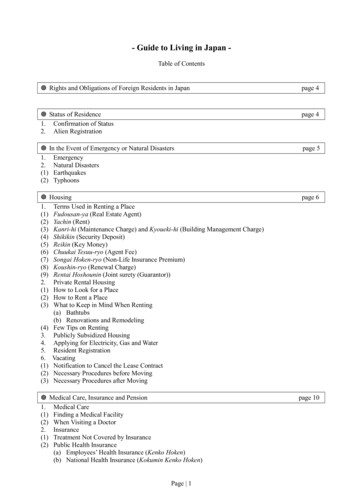

Original article: Child Abuse in Japan Table 1 Main Surveys of Known Cases of Abuse in JapanAUTHORSSAMPLECASESMinistry of Healthand Welfare, 1948(cited by Ikeda, 1995)92 child guidance centres1063 cases of abuse306 cases of abandonment366 of child labourMinistry of Healthand Welfare (1973)139 child guidance centres26 cases of abuse139of abandonment137 of neonaticideIkeda (1979)cases in Chiba Prefecturein 1976 and 197748 child abuse casesMedico Legal Society(Naito, 1984)autopsies on battered childrenbetween 1968 and 1977186cases, 130 killedbiological parentsCouncil of Child WelfareInstitutions (1980)22,583 children in404 childwelfare institutions3,000 (13%) abused154 sexual abuseChild Abuse Study Group(1985)164child guidance centres in 1983416 cases: 54% physical,12% psychological, 27% neglect,11% sexual abuseKobayashi, N. & Naito(1986)63.5% response rate from 1,006hospitals with paediatric casesin 198390 hospitals reported23 1casesDirectors of Child GuidanceCentres (1989)167 centres in 6 months of 19881,039 cases:26%physical,22% abandonment, 38% neglect,7% psychological, and 3% childrenforbidden to go to schoolKobayashi, M. eta1(1995)Osaka between 1983and 1987403 cases: 57% physical,36% neglect, 7% sexualKobayashi etal(1993)Osaka in 1990318 cases reportedSaitoetal(l994)49.2% response rate from 535protective care facilities onchildren entering March 1991to March 1992comparison of data on579 abused and 263control childrenUchiyama (1994)casesof abuse known to policein 1992250cases, 57% physical abuse,21% neglect, 12% abandoned,10% sexual abuseInformation in Table mainly adopiedfrom I k d a (1995)Four main explanations are invoked to explain this lowincidence. First, that child abuse and other socialproblems occur less frequently in Japan compared toWestern societies for cultural reasons. Second, thatconcepts of child maltreatment are qualitatively differentin Japan. Third, that a lower definitional threshold forabuse is applied resulting in lower abuse statistics inJapan. Fourth, that situations that most would agree to beabusive do commonly occur but are hidden from publicview.Culture ofcareAccording to this view, cultural differences makeviolence more or less common in different societies(Levinson, 1989). There are large social culturaldifferences between Japan and the West and one wouldexpect some of these differences to be reflected in familyrelationships (Goodwin, 1995), child care (Hendry, 1986),and the nature and extent of child abuse. Although sucharguments seem parsimonious, the difficulty is in beingsure that the cultural differences have an effect in the wayhypothesized. For all the examples of cultural effectsChildP.yychology&Psychiatry Review Volume 1, No. 1.199613

Original article: Child Abuse in Japanlikely to minimise the extent of abuse, counter examplesand arguments can be found.the family home or by teachers in schools. Publicreputations are also very important in Japan, whichrestricts people’s willingness to reveal negative aspectsabout their family or school.Value of childrenJapanese society values children; young children inparticular are considered to be favoured by the gods andto be able to do as they wish with little parentalintervention. Maybe societies that value children are lesslikely to abuse them.Although children are highly valued in Japan, this doesnot necessarily mean that all children are so valued or thata desire 10 care well for children is always achieved inpractice. In a survey of cases of child abuse known tohospital paediatric departments in 1986 (Tanimura.Matsui & Kobayashi. 1990) it was found that 10% ofcases involved multiple birth children (20 sets of twinsand one set of triplets). which contrasts with a 0.6% ratefor twin% in the general population. For 17 of thesemultiple birth cases, only one of the children was abusedand 16 of these 17 abused children (94%) had congenitalor developmental disease or retardation. None of themultiple birth cases where more than one child wasabused had such problems. The authors conclude thattwins are at high risk of abuse in Japan, and the risk isparticularly high for developmentally impaired membersof twin pairs.Traditional family and gender rolesMaybe abuse is less likely to occur in Japan because thetraditional family is a strong institution with traditionalgender roles of male breadwinner and female housewifeand carer for the children. Non traditional family formsand lack of stable carers are risk factors for abuse.Whatever one’s view of the appropriateness of traditionalgender power relations, they provide a more securecommunity and individual family base for child care andstable selective attachments than the high rates of divorce,single parents, and reconstituted and other non traditionalfamily forms found increasingly in the West. The counterargument is that family and traditional gender roles are sostrong in Japan that firstly, they create stress for parents,and secondly, what occurs in families is not open toinspection or to intervention by outsiders. There are thusfew limits on parental powers over their children. Anextreme example is when a father in serious economic orother difficulties commits family suicide believing thatthis would be best for his wife and family.Socio-economic and other stressorsA further counter argument is that despite the high valueput on children in Japan, it was only relatively recentlythat infanticide and the sale of children were totallyhalted. Child abuse statistics are low, but child homicidesare relatively high according to maternal and child healthstatistics. Homicide is the seventh most common cause ofdeath for children aged 1 to 4 years with a rate of 0.7 per100,000children (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 1992).Deaths of infants from presumed abuse is 7.4 per 100,000live births. which compares to rates of 9.8 and 3.9 per100,000 in the United States and the United Kingdom,respectively (Belsey cited in Unicef, 1994).Parental methods of controlIt can be argued that parental methods of control in Japanare principally non interventive and depend upon parentalpatience and example, and are less likely to lead to abuse.The idea is that the child internalises the parental modelrather than it being imposed by intervention andpunishment. In the West, physical punishment iscommon, but it is criticised by some commentators asbeing ineffective, an infringement of children’s rights,and being the (wrongly) currently acceptable end of thecontinuum that ends in physical abuse (Leach, 1993). Acounter argument is that, as in the West, much domesticviolence occurs in private in the family and that the lackof public displays of violence does not mean that thesemethods are not used behind closed doors by parents in14Japan is a relatively homogeneous and stable societywithout the racial, religious, or socio-economic divisionsfound in many Western countries. Although there areeconomic differences in society, there are not large underclasses of people living in severe socio economic stressnor is there a sub-culture of public violence. Suchstressors are statistical risk factors for child abuse for bothfamilies and neighbourhoods in the West (see forexample, Gelles & Cornell, 1990).A counter argument is that there are many stresses inJapanese society to compensate for the lack of Westernstyle stresses. Families live in cramped housing, mothersoften have to care for their aged in-laws or other relatives,fathers work very long hours and rarely see their childrenor help in the house, mothers are under pressure to begood mothers and to cope in their child rearing role.Children or families who are considered to be odd in anyway (including Japanese who have lived some timeabroad) may be rejected, criticised, and not offeredsupport by others. Also, Western style expectations ofindividual needs and personal development are spreadingin Japan leading to aspirations that many are unable tofulfil in the current society. Many women, for example,aspire to life long working careers, whilst most companiesstill prefer to only employ young women who areencouraged to leave for marriage and parenthood after afew years of work.

Original article: Child A D m e i i i JapanResearch has shown that socio-economic and otherstressors are common in the known cases of child abuse.A recent survey in Osaka (Kobayashi et al., 1995) foundthat parents in abusive families were often judged to havepersonality problems, marital conflict, to be sociallyisolated, and be suffering from economic stress. Childrenhad behavioural problems and developmental delay.Similar findings of high rates of child, parental, and familyproblems were also reported by the study by Directors ofChild Guidance Centres (1989). Further information oncase characteristics is provided by a survey comparingabuse cases with other cases entering protective carefacilities in Japan (Saito, Tezuka & Hasegawa, 1994). Theabuse cases were significantly more likely to involvechildren who had been premature, to have developmentalproblems, to be developmentally delayed, to have sufferedinjuries, and to exhibit emotional and/or behaviouraldisturbances. The parents were also more likely thancontrols to have divorced, to live in reconstituted familiesand to have abused alcohol. In physical abuse cases, fatherswere more likely than controls to have been violent towardstheir wives. In neglect cases, they were more likely to havedeserted their families. Mothers were more likely thancontrols to have experienced depression, to have desertedtheir families, to have had extra marital affairs, and to haveover spent money. The control group cases were morelikely to have had imprisoned step fathers andschizophrenic mothers. Though of interest, the results aredifficult to interpret without details of the control groupcases and the manner in which case workers completedquestionnaires on abuse and control cases.Concepts of maltreatmentAnother version of the cultural argument is that childabuse exists in Japan but is different in kind to abuse inthe West. Concepts of appropriate and inappropriate childcare including child abuse are intrinsically sociallydefined concepts so are likely to be defined differently indifferent cultures. Different forms of child care anddiscipline may therefore be considered acceptable andunacceptable in Japan. People tell me of being punishedin childhood by being shut in cupboards or out of doorsrather than receiving physical chastisement that is socommon in the West. Others tell me of the shock ofvisiting Britain and seeing parents walking their youngchildren with reins as if they were walking their dog.Leaving a baby to sleep at night alone in another roomrather than with their mother is also thought to be ratherheartless.There may also be cultural differences in the extremes ofinappropriate and abusive child care. In Britain andAmerica there are distressing cases of sexual homicide ofchildren. In Japan, I hear about cases of family suicideand cases of emotional abuse. For example, I have mettwo women whose fathers ate the family pet (a fish and adog) as an act of spite towards their daughters. It is difficult to make general statements about countrieson the basis of anecdotal statements and individual cases,but some preliminary data on cultural differences i nconcepts of appropriate discipline is provided by a studentsurvey (Cough, 1995b). Japanese female students weresignificantly more likely to consider physical restraint bytying, loss of privileges, and light spanking with a belt tobe abusive than American members of the publicsurveyed by Rosonke and Pelton (1982). In contrast, theJapanese students were significantly less likely thanAmerican respondents to label squeezing to produce pain,slapping of face, or locking a child in a room as abuse.Also, 22% of Japanese female students thought itacceptable to leave a child under two years of age alone ina car for over ten minutes whilst the parents wentshopping. Such cultural differences were illustratedrecently by the arrest of a Japanese couple in Californiafor leaving their young child alone in their car whilstshopping.Research by Noh Ahn and Gilbert (1992) has also showncross cultural differences in the appropriateness of parentand child bathing, sleeping, and intimate touching invarious cultures. Asian respondents (living in the UnitedStates and not including any Japanese) accepted parentchild bathing and sleeping for significantly older childrenthan Caucasian respondents. Genital touching also haddifferent symbolic meaning with nearly half ofVietnamese and Korean respondents but only 2% ofCaucausian respondents considering it acceptable for agrandfather to touch playfully his three year oldgrandson’s genitals with pride.The danger with culturally based arguments is that theyare easy to over apply if not based on empirical researchthat has excluded other explanations. For example, therehave been stories in the press of mother-son incest arisingfrom the strong nature of this relationship in Japan and theimportant maternal role of ensuring the son succeeds atschool. Children are very busy with education, manygoing almost daily to evening crammar schools. Better forthe mother to service the son than that he should wasteimportant time and emotional energy experimenting withrelationships with same aged girls. A telephone hot linefor adolescents received several calls from males allegingmaternal incest which has led some to argue that this is thedominant form of sexual abuse in Japan (Kitayama &Arahari, 1994). The evidence, though, is that nearly allcases of sexual abuse known to police or health andwelfare professionals are, just as in other countries,perpetrated by males against male and female children.There is also considerable evidence of male sexualinterest in female children shown by the Ikeda and Satoh(1992) student survey and the extent that the pornographyand prostitution industry is preoccupied with images ofschool age girls.Cultural differences must have some effect on theprevalence of child abuse in Japan but it is dangerous ChrldPsychology& Psychtotry Review Volume 1,No. 1,199615

Uriginal artrcle: Child Abuse in Japanimmediately to accept seemingly parsimonious culturalexplanations. Many cultural explanations are simplistic ininvoking a number of single variable differences ratherthan determining the nature of interactions betweenvariables. There is a tendency, for example, to suggestthat people are more polite, less aggressive, or less likelyto abuse children in a particular society, rather thandetermining under which circumstances people are moreor less polite or aggressive (or likely to maltreat children,however that is defined).used for intra and extra familial sexual abuse, but not forextra familial physical abuse by strangers. The coverageof terms is more consistent in Japan with both sexual orphysical assaults by strangers being described as assaultsrather than child abuse. Thus the frequent sexualmolestation of girls and young women by men on publictransport and in the street (Ikeda & Satoh, 1992) isconsidered unacceptable but would not be normallydescribed as child maltreatment. An assault by a strangeris simply an assault.Definitional thresholdsAwareness explanationsAnother possibility is that child abuse fitting Westerndefinitional criteria occurs frequently in Japan but is notlabelled as such due to higher level or differentoperational criteria. The serious nature of the known casesof child abuse in Japan suggest that high definitionalcriteria are being applied with the less extreme cases ofphysical or psychological abuse being ignored or beingseen as other types of family difficulties.Another possible explanation is that child abuse iscommon but largely hidden in Japan. Many people havedetailed the way that child abuse occurs in secret andrequires high awareness and confidence in children,parents, other members of the public, and professionals toopenly identify (Finkelhor, 1993). Twenty to thirty yearsago, there was little awareness or identification ofphysical, and particularly sexual abuse in the West. Theslightly higher rates of reported sexual abuse by youngerrespondents in some population prevalence studies (e.g.Siegal et al., 1987) suggest that there may have been aslight increase in prevalence of sexual abuse in the lasttwenty years, but not sufficient to account for the massiveincreases in reported cases. The implication is that sexualabuse was occurring before but was not being identified.The survey of cases known to a range of agencies inOsaka Prefecture (Kobayashi et al., 1995) found that mostknown cases concerned physical abuse (57%) and neglect(37%) with few cases of sexual abuse (7%). The casesidentified were relatively severe with 5 % deaths, 52% lifethreatening and the remainder classified as moderate.There were high rates of family stress and other child andparent problems and 35% of children were admitted toprotective care. This is in contrast to much milder casesknown to a telephone hot line in Osaka (Kobayashi et al.,1995). There are therefore likely to be a group ofmoderate cases existing between the serious casesidentified by the main health and welfare and the mildcases known to the telephone hot line.Cases known to the police have been studied byUchiyama (19Y4) with 250 cases being identified in oneyear. The majority were physical abuse cases (57%), butwith many cases of neglect or abandonment (33%). Theserious level of the cases is indicated by the finding thatnearly 16% of the children were dead though some ofthese were abandoned dead infants who may have beenborn dead. The 25 cases of sexual abuse all concernedfemale victims.The effects of definitional criteria is also shown by theclassification of child homicides. Child homicides arerelatively frequent in Japan, according to health statistics(Ministry of Health and Welfare, 1992;Belsey, 1993),butmany of these cases are not included in the main childabuse data derived from child guidance centres. Similarly,family suicide where a parent kills himself, his children,and his spouse, is not usually considered under the termchild abuse, even though it equates to intra-familial childhomicide. There are also differences in which forms ofintra and extra familial assaults on children are labelledchild abuse. In the West, the term child abuse is typically16The rapid change in awareness and rates of reportingindicate the extent that child abuse was previously hiddenfrom view in many Western countries. The same may betrue for present day Japan, particularly when there is suchpotential loss of face from being perceived as failing as aparent or from being known to have been victimised. Theeffect of cultural factors may thus be upon the process ofcase identification rather than the actual occurrence ofabuse.Service responsesChild guidance centres are the main local governmentagency responsible for assisting children and families inneed. There is little known about the cases of mild abuseknown to child guidance centres and other agenciesbeyond the questionnaire surveys summarised in Table 1.The best data is from the Osaka survey (Kobayashi et al.,1995) which found that cases were seen by a range ofservices, but predominantly by child guidance centres(89%), family and child guidance rooms (37%), welfareoffices (37%), and schools and nurseries (44% and 25%respectively). There was less multi-agency involvementin cases referred to hospitals and medical clinics. In overa third of cases (35%), the children were placed in achildren’s home.Legal powers of intervention in families where there ischild maltreatment are difficult to obtain because of the

Original article: Child Abuse in Japancomplex nature of the law and the reluctance to intervenelegally in domestic issues. The simplest methods of legalintervention require parental consent and without this,workers may not have the evidence or the motivation topress for other forms of legal intervention. Even wherelegal powers are obtained, it is difficult to legally preventthe parents removing the child from such care. I amcurrently aware of a father who frequently injures hisyoung infant in violent, seemingly jealous outbursts, andwho restricts his wife from leaving the house orcontacting anyone by telephone. The lead agency in thecase is a hospital which offered non specific counsellingwhich the father has now refused. The staff say they arepowerless to intervene but are very anxious about thechild’s welfare, particularly as they recently had a childabuse death in another case. Child protection interventionlaws do exist, but are complex and seem not to be fullyutilised. That these laws can be applied is shown by thestate response to the Aum Shinrikyo cult, whose membershave been accused of murdering underground trainpassengers with Sarin gas. Many of the children of cultmembers were removed into care with seemingly littleevidence of immediate risks to the children indicating theuse of a much lower than usual criteria for intervention.Health and welfare services in all countries develop avariety of special extra services for children and familieswith problems, but in Britain an extra level of formallymonitored casework has been developed for childprotection and children with special needs (Gough,1995b). There is no such special formal caseworkresponse for child protection in Japan. Most of theidentified cases of child abuse are known to childguidance centres and will receive casework aimedtowards engaging the family and supporting them in theirrole of child care. Psychologists and psychiatrists maybecome involved in a minority of cases and such work isoften psychodynamic in approach. In addition to casesseen in routine work, there is a number of special projectsdeveloped by interested professionals and members of thepublic in different parts of Japan. As has happened inmany other countries, it is often medical doctors who setup these early projects even if the medical profession as awhole is not particularly concerned with the issue ofabuse.Osaka is currently very active in this area with theAssociation for the Prevention of Child Abuse (APCA) inOsaka, a multi-professional group that holds conferences,developed a child abuse handbook for professionals, andstarted the first child abuse telephone hot line service.Leading members of APCA also started the Osaka ChildAbuse Prevention Research Group that undertook theOsaka surveys (see Kobayashi et al., 1995). Osaka isunusual to the extent that these developments areintegrated into the mainstream health and welfareservices, although paediatricians are still unhappy aboutthe low level of intervention provided by child guidancecentres to the cases that paediatricians refer to them(Kobayashi, M., personal communication).There are many other smaller special projects in otherparts of Japan. Tokyo has several very separate groupsincluding paediatricians at the National Children’sHospital, the Center for Child Abuse Prevention (CCAP)with its telephone hot line and a newsletter, and theheadquarters of the Ministry of Health and Welfare.Recently, special interest groups in sexual abuse havedeveloped. For professionals and survivors, there is the‘We’ group in Yokohama. For survivors, there are severalgroups including SCSA (Stop Child Sexual Abuse).Future developmentsIt is likely that public and professional awareness of childabuse will continue to increase resulting in increased caseidentification. The Ministry of Health and Welfare hasresponded to the increased awareness and concern aboutchild abuse by beginning to designate some establishedchild care services as special centres for child abuse.There are benefits from these designated centres beingpart of mainstream services, but sceptics worry that thedesignation is mainly cosmetic and that little will beachieved in practice.The development of child abuse work in the short term ismore likely to follow on from increased awareness throughthe public and professional media and the work of theindependently funded child abuse initiatives. There is alsomuch scope for research to address issues such as the extentof population prevalence and Japanese professional andpublic perceptions of what constitutes child maltreatment.Adifficulty is funding because there is no perceived need forsuch research, and because there is generally less funding ofsocial science research in Japan. Research is likely to followthe pattern in the West where the relatively unproductivestudies of the defining characteristics of known cases or ofthe efficacy of special child abuse interventions are the mostlikely to be funded (Gough, 1993).My main contribution to the development of child abuseissues in Japan has been in initiating some cross culturalresearch on perceptions of child maltreatment and arranginga two day symposium and seminar in Tokyo in 1994 underthe auspices of the International Society for the Preventionof Child Abuse and Neglect (Ispcan), in association withCCAP, APCA, and the ‘We’ Group, with a special seminaron survivors’ issues organised by SCSA. This meetingwithfour invited Western speakers provided the first opportunityfor these groups to work together, and has led to preliminarydiscussions about the formation of a Japanese national childabuse society with an annual national child abuseconference. Hopefully such dialogue can enable Japan tolearn from the pitfalls experienced by Western approachesto child abuse and to adapt this knowledge to the particularneeds of Japanese children and society.ChildPsychology& Psychiatry Review Volume 1, No. 1,199617

Original article: Child Abuse in JapanReferences(references with an asterisk

the Open University Course set book (Stainton Rogers, Heliey & Ash, 1989), a medical guide to the recognition of abuse (Rose, 1985), the Maria Colwell Report . centres is low, at about 0.07 cases per thousand children (based on 2,000 cases per year as reported by Directors of Public Child Guidance Centres, 1989), much less than the .