![[2021] Ccj 5 (Aj) Bb Appellate Jurisdiction On Appeal From The Court Of .](/img/30/2021-ccj-5-aj-bb.jpg)

Transcription

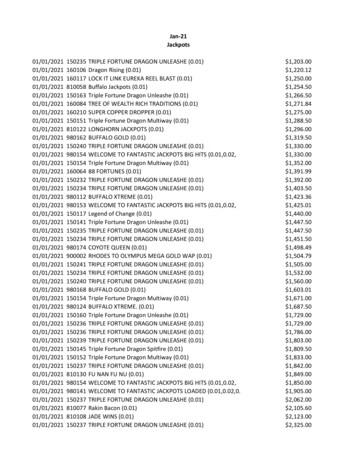

[2021] CCJ 5 (AJ) BBIN THE CARIBBEAN COURT OF JUSTICEAPPELLATE JURISDICTIONON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL OF BARBADOSCCJ Civil Appeal No BBCV2020/002BB Civil Appeal No 6 of 2010BETWEENESTATE OF MARJORIE ILMA KNOX(Acting herein by EUGENE ESTWICKJOHN KNOX who was appointed as herpersonal representative for the purposeof these proceedings by Order of Dr theHon Justice Olson Alleyne made on the10th day of October 2018)APPELLANTJOHN VERE EVELYN DEANEERIC ASHBY BENTHAM DEANEDeceased, acting herein by RICHARDBASIL MARK DEANE duly substitutedby Order of the Hon Madam JusticeSandra P Mason JA made on the 27th dayof February 2013OWEN BASIL KEITH DEANEELIZABETH TESS ROHMANNLYNETTE RACHEL DEANEMURIEL EILEEN DEANEOWEN GORDON FINDLAY DEANEERIC IAIN STEWART DEANEKINGSLAND ESTATES LIMITEDCLASSIC INVESTMENTS LIMITEDPHILLIP VERNON NICHOLLSFIRST RESPONDENTSECOND RESPONDENTANDBefore the Honourable:THIRD RESPONDENTFOURTH RESPONDENTFIFTH RESPONDENTSIXTH RESPONDENTSEVENTH RESPONDENTEIGHTH RESPONDENTNINTH RESPONDENTTENTH RESPONDENTELEVENTH RESPONDENTMr Justice A Saunders, PCCJMr Justice J Wit, JCCJMme Justice M Rajnauth-Lee, JCCJMr Justice D Barrow, JCCJMr Justice P Jamadar, JCCJAppearancesMr Alair Shepherd QC, Mr Philip McWatt and Ms. Sumaya Desai for theAppellantMs Doria Moore for the Second RespondentMr Leslie Haynes QC and Mr Kashawn Wood for the Ninth RespondentMr Barry Gale QC and Mrs Laura Harvey-Read for the Tenth Respondent

Practice and Procedure – Attachment (Garnishee order) – Whether judge used correctprocedure in making order - Third party rights – Whether appellant entitled to assertinterest of third parties – Whether court erred in finding debt owed could be set off.Constitutional law – Constitution – Judiciary - Exercise of judicial power afterdemitting office - Judgment pronounced by the Court of Appeal after two judges ofhearing bench resigned - Whether former judges lack authority to concur in judgment– Whether judgment a nullity - Constitution of Barbados 1966, s 84(2)(b).Constitutional law – Separation of powers – Executive and judicial powers - Formerjudge of Court of Appeal appointed to Office of Governor General - Judgmentpronounced after assumption of office – Whether separation of powers principlebreached – Whether court independent and impartial.Constitutional law – Fundamental rights – Right to a fair hearing within a reasonabletime – Delay – Judgment – Delay of four years in delivery of judgment – Whetherdelay prejudiced the Court’s ability to deliver judgment – Whether delay unacceptable– Constitution of Barbados 1966, s 18.Marjorie Ilma Knox, deceased (“Knox”), was a judgment debtor of the respondents byvirtue of a court order to pay them costs (“the costs”) in different amounts. Paymentof the costs remained outstanding, and the respondent Kingsland Estate Ltd. (“KEL”)became indebted to Knox, one of its shareholders, on account of dividends due toKnox. On the application by the various respondents for a garnishee or attachmentorder against the costs, the trial judge ordered that the costs should be satisfied byattaching the dividends, due by KEL to Knox. One of the amounts the judge orderedto be satisfied from the dividends was the amount Knox owed to KEL as part of thecosts. The trial judge ordered that KEL could ‘set off’ this sum against its obligationto pay dividends to Knox. Knox appealed.The Court of Appeal took some four years to deliver its judgment. During this timetwo of the justices of appeal who heard the appeal, Mason JA and Burgess JA,demitted office. Mason JA became Her Excellency the Governor General of Barbadosand Burgess JA became a judge of this Court. The judgment of the Court of Appealwas pronounced on 26 June 2020. The Court dismissed Knox’s appeal against theattachment order. Both retired judges concurred with the reasons and the result andsigned the judgment.

Knox appealed to this Court on two procedural grounds, concerning the steps taken bythe judge in making the order for attachment and the order for ‘set off,’ and on oneconstitutional ground, concerning the right to a fair trial, judicial delay and theseparation of powers.On the procedural grounds, Knox submitted that the trial judge erred by failing to orderthat certain identified third parties should be served with the application. Knoxasserted that the third parties owned the beneficial interests in the dividends. None ofthe third parties ever made an application to intervene in these proceedings. In respectof the alleged third-party rights, the Court, in a judgment authored by Barrow JCCJ,found that the Court of Appeal correctly decided that the trial judge was right to refuseservice of the application on the third parties. Such an order would needlessly havedelayed the substantive application for the attachment order that was before the judge.Knox was not entitled to apply to ‘join’ them ‘as interveners,’ nor advance argumentson their behalf. In respect of the order that KEL could ‘set off’ the debt owed to it bythe appellant, the Court found that KEL was entitled, as of right, to withhold whatKnox owed to KEL from what KEL owed to Knox and it did not matter that the judgeused the term “set off”. The Court found that on both procedural grounds the appealfails.In respect of the constitutional ground, Knox argued that the Court of Appeal’sjudgment was a nullity because the authority of the retired judges to act as appellatejudges had expired and they had not re-taken the oath of judicial office before deliveryof the judgment. Knox also argued that since, at the time the judgment was delivered,the former Mason JA had become the Governor General, this meant the Bench thatgave the decision was not an independent and impartial tribunal as it then compriseda member of the Executive branch of government. This circumstance, it was said,created a breach of the separation of powers principle.The Court, in a judgment authored by Saunders PCCJ, found that Section 84(2)(b) ofthe Constitution empowers a person to sit as a Judge for the purpose of deliveringjudgment or doing any other thing in relation to proceedings which were commencedbefore them before they resigned, without re-appointment or re-taking of the judicialoath. The Court found that the principle of separation of powers was not breached and

the Court of Appeal was independent and impartial. Everything that was done inrelation to the judgment by the former Mason JA was done by her not in her capacityof Governor General but rather as a former judge. There was no evidence to suggestthat the former judge channeled any executive authority or exercised any executivepower or discretion. The act of affixing her signature to a judgment in respect ofproceedings that were commenced before a Bench that included her while she was ajudge of the Court of Appeal did not breach the separation of powers principle or thejudicial independence provisions of the Constitution and was specifically catered forby Section 84(2)(b) of the Constitution. The Court found that on the constitutionalground the appeal also fails.The Court, however, commented that the delay by the Court of Appeal in deliveringthe judgment was serious and unacceptable but found that the delay did not prejudicethe ability of the Court of Appeal to render its decision.In a concurring judgment Jamadar JCCJ commented on sections 18 and 84 of theConstitution of Barbados as they relate to delay in the delivery of judgments, findingthat based on an outer time standard of reasonableness for the delivery of judgmentsof six months, this delay of four years was unacceptable. In cases such as this, theminimum that should be done is to offer an explanation to the parties for the delay andan appropriate apology not that these could exempt the default, but maybe they couldrescue in some small measure public trust and confidence in the administration ofjustice in Barbados.The appeal was therefore dismissed.Cases referred toAhnee v DPP [1999] 2 AC 294; Attorney General of Guyana v Richardson [2018] CCJ17 (AJ), (2018) 92 WIR 416; August v R [2018] CCJ 7 (AJ), [2018] 3 LRC 552; BataShoe Company v CIR (Guyana HC, 15 January 1975); BCB Holdings Ltd v The AttorneyGeneral of Belize [2013] CCJ 5 (AJ), (2013) 82 WIR 167; DPP v Mollison [2003]UKPC 6, (2003) 64 WIR 140; Green Browne v R [2000] 1 AC 45; Griffith v R [2004]UKPC 58, (2004) 65 WIR 50; Hinds v The Queen [1977] AC 195; Knox v Deane [2005]UKPC 25, (2005) 66 WIR 104; Knox v Deane [2012] CCJ 4 (AJ), (2012) 80 WIR 71;Knox v Deane [2020] CCJ 5 (AJ) BB; Knox v Deane (Barbados CA, 26 June 2020);Martin v Nadel [1906] 2 KB 26; Orozco v The Attorney General [2020] 2 LRC 501; R

v Bow Street Magistrates Ex p Pinochet (No 2) [2000] 1 AC 119; R v Home SecretaryEx p Fire Brigades Union [1995] 2 AC 513; Reid v Reid [2008] CCJ 8 (AJ), (2008) 73WIR 56; Scantlebury (Mormon) v R (2005) 68 WIR 88; Singh v Attorney General[2018] CCJ 3 (AJ); Sookar v The Attorney General (Trinidad and Tobago HC, 4November 2014); Sookar v The Attorney General (Trinidad and Tobago CA, 28October 2020); The State v Khoyratty [2006] UKPC 13, [2007] 1 AC 80; Zuniga vAttorney General of Belize [2014] CCJ 2 AJ, (2014) 84 WIR 101Legislation referred toBahamas - Constitution of the Commonwealth of the Bahamas, Rev Ed 2000;Barbados - Companies Act Cap 308, Constitution of Barbados, Rev Ed 1971,Supreme Court of Judicature Act Cap 117A; Canada - Judicature Act RSNS 1989, c240, Supreme Court Act RSBC 1966, c 443; United Kingdom - Judicial Pensions andRetirement Act 1993, c 8Other Sources referred toMcIntosh S, Caribbean Constitutional Reform: Rethinking the West Indian Polity(Caribbean Law Publishing Co 2002); Robinson T, Bulkan A and Saunders A,Fundamentals of Caribbean Constitutional Law (Sweet & Maxwell 2015); Rules ofthe Supreme Court of Judicature 1982 (Barbados); Supreme Court (Civil ProcedureRules) 2008 (Barbados)JUDGMENTofThe Honourable Mr Justice Saunders, President and The Honourable JusticesWit, Rajnauth-Lee, Barrow and JamadarDelivered byThe Honourable Mr Justice BarrowandThe Honourable Mr Justice Saunders, PresidentandCONCURRING JUDGMENTofThe Honourable Mr Justice JamadarDelivered on the 29th day of April 2021

JUDGMENT OF THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE BARROW, JCCJ:[1]The true subject matter of this appeal is the enforcement of a Privy Council orderfor the payment of costs made against the appellant, Marjorie Ilma Knox,deceased, which Worrell J ordered should be satisfied by attaching a debt(formerly known as a garnishee order) due to her in the form of dividends payableby Kingsland Estate Ltd (KEL), the ninth respondent (the garnishee). Thedetermination of the appellant to thwart the efforts to collect the award of costsof 247,500, which was registered as an order of the Supreme Court of Barbados,has produced further litigation steps involving 11 respondents, three QueensCounsel, a commensurate number of juniors and instructing attorneys at law,spanning more than a decade, that are out of proportion to the objective value ofthe true subject matter of this appeal.1[2]The grounds of the appeal that has come to this Court encompass three issues,two of which concern the procedure used by the judge in making the order forattachment and will be considered first. The third issue raises a matter offundamental constitutional law relating to the right to a fair trial, judicial delay,and the separation of powers, commanding deeper consideration. The twoprocedural issues were that the Court of Appeal was wrong in upholding theattachment order of the trial judge who allegedly erred in refusing to consider theclaims of third-party beneficiaries to the attached debt and also allegedly erred inordering that KEL could set off, against its obligation to pay dividends of 749,692.50 to the appellant, the claim of KEL itself for 284,016.75 from theappellant. These procedural issues call for no summary of background facts.2Third party rights[3]The order for the attachment of the debt due to the appellant from KEL, thegarnishee, was made by Worrell J on an application by three of the respondents,See Knox v Deane [2012] CCJ 4 (AJ), (2012) 80 WIR 71 at [11] for a reference to the ‘five other actionsin the courts of Barbados in which the courts have made orders for costs against Mrs. Knox in connectionwith Kingsland Estate’.2For some background information, see the judgment of the Court of Appeal of Barbados in Knox vDeane (Barbados CA, 26 June 2020) as well as the judgment of the Privy Council in Knox v Deane[2005] UKPC 25 and of this Court in Knox v Deane [2012] CCJ 4 (AJ), (2012) 80 WIR 71.1

namely, Respondents numbers two, nine and ten.3 As indicated, the sums duewere by way of the award of costs and were in the amounts of 228,266.76 forrespondent number two, 173,452.70 for respondent number 10 and 284,016.75for KEL (respondent number nine). The procedure for the attachment of debts isnow contained in Part 50 of the Supreme Court (Civil Procedure Rules) 2008(CPR 2008).4 The particular provision that this Court must consider is, insubstance, Part 50.11, which states:Claim to a debt by person other than judgment debtor50.11. (1) This rule has effect where the court is aware from informationsupplied by the garnishee or from any other source that someone other thanthe judgment debtor(a) is or claims to be entitled to the debt; or(b) has or claims to have a charge or lien over or on it.(2) In this rule, “lien” means a right to retain possession of goods toprotect a debt.(3) Where this rule has effect, the court may require the judgmentcreditor to serve on any person who may have such an interest as isset out in sub-rule (1) notice of(a) the application for an attachment of debt order; and(b) any hearing fixed by the court.(4) The notice must be served personally unless the person is a bodycorporate, or the court directs otherwise.(5) Notice must also be served on(a) the garnishee; and(b) the judgment debtor.(6) A notice under this rule must contain a warning to every personon whom it is served that if he does not attend court, the court mayproceed to decide the issue in his absence.[4]The appellant had urged the judge to order certain identified persons to be served,pursuant to the principle in Part 50.11 (3), because the beneficial interest in thedividends was owned, she asserted, by those third parties under four instruments,3Respondents numbers 2, 3, 7 and 11 had assigned their awards of costs to KEL (Respondent numbernine) and Respondents numbers one, four, five and six had assigned their awards of costs to Respondentnumber two.4As a matter of accuracy, at the time the application was made Order 49, r 6 of the Rules of the SupremeCourt 1982 (RSC) applied, because these were ‘old proceedings,’ in the language of Pt 73.3 of CPR2008, to which those latter Rules did not apply. The record of appeal reveals that over the years that theproceedings spanned, CPR 2008 came to be applied.

the particulars of which are not presently material.5 Worrell J was aware of theexistence of these instruments since he adverted to them in considering theapplication for service on the third parties benefitting under those instruments.The judge refused to order such service or adjourn the proceedings but did notgive reasons for his decision. The Court of Appeal declined to reverse the judgeon the point, for the reason that the alleged passing of the beneficial interest inthe dividends under the instruments was not binding on KEL, whose legalobligation under s 179 of the Companies Act was to pay the dividends to theregistered shareholder without reference to any trust. In that court’s view, therewas no reason for Worrell J to have added them as parties to the proceedings -which, with respect, was not quite the order the appellant sought; the appellantapplied for the rather novel order ‘to join’ them as ‘interveners.’ That confusiondoes not matter, however, because the determination that the third parties had noclaim as against KEL for payment of the dividends was also good reason forrefusing ‘to join’ them as ‘interveners.’[5]Before this Court, counsel for the appellant acknowledged that the appellantremained the legal owner of the shares and, hence, of the right to the dividends.However, he insisted that the alleged rights to the dividends of the allegedbeneficial owners should have been recognized and, more to the point, that it wasunfair to those persons and a breach of the constitutional right to a fair hearingfor the judge to refuse to order that notice of the proceedings be served upon them.This stance raised two basic concerns: why should the Court hear representationsfrom counsel for the appellant about ordering service upon the holders of thesealleged beneficial rights when these persons have steadfastly refrained frommaking representations to any court? And why should the Court permit counselfor the appellant to argue the existence of these rights of others, which were notthe rights of his client? In short, what business of the appellant was it -- even ifthe judge had erred in deciding not to order service?5For information about these instruments, see the discussion at [18]-[22] of the judgment of the Courtof Appeal in Knox v Deane (Barbados CA, 26 June 2020) and the summary of Nelson JCCJ in Knox vDeane [2012] CCJ 4 (AJ), (2012) 80 WIR 71 at [5].

Who may apply?[6]In relation to the first concern, why this Court should hear from counsel for theappellant and not the third parties, counsel argued that the effect of the judgehaving refused to order service on the third parties was to exclude them frommaking representations, so it was left to the appellant to pursue the point. Counselreferred to no principle or authority for the proposition that the judge’s decision,refusing the appellant’s application, was binding on the third parties who werenot parties to that application. Nothing was identified that prevented the thirdparties from, subsequently, making their own application. It is elementary that itis the holder of a right or status who has the standing to assert it before a court,and that a person who does not hold the right or status has no standing or right tobe heard. This Court would readily conclude that the judge must have decided, asindeed was the right decision, that he had no proper basis for acceding to the novelapplication by the appellant to join ‘interveners,’ when there was no applicationfor leave to intervene or to be heard by the proffered interveners. Such an orderwould needlessly have delayed the substantive application for the attachmentorder that was before the judge.[7]In fine, it appears that nothing prevented the third parties from applying to beheard to assert their alleged claim to the dividends. This Court, therefore, issimply left to proceed on the basis that these persons have chosen not to asserttheir alleged rights in these proceedings and need not speculate as to the reasonfor this inanition.Double payment[8]On the question whether it was right for the Court to entertain argument from theappellant asserting the interests of third parties, counsel relied on Martin v Nadel6for the proposition that payment by a garnishee of a debt to one creditor couldleave the garnishee liable to pay the same debt to another creditor, even if the firstpayment was made in compliance with a court order. Applied to the facts of thiscase, counsel submitted, the judge should not have made the order to pay the6[1906] 2 KB 26.

attached dividends to the respondents because that order did not extinguish theright of the beneficiaries to payment of the same dividends.[9]The submission is nimble but does not withstand scrutiny. In Martin v Nadel7 thejudgment debtor had deposited a sum of money with the Berlin branch of a bankand, on the strength of that deposit, obtained from the bank’s London branch aguarantee from the bank to pay an equivalent sum, should the court in Englandmake an award of costs in pending litigation against the judgment debtor. Suchan award was made in favour of the judgment creditor, and the bank satisfied theaward. There remained a balance of the amount deposited in Berlin, due as a debtfrom the bank to the judgment debtor. The judgment creditor obtained, inEngland, an attachment order against the London branch to pay to the judgmentcreditor the balance held at the Berlin branch which, as mentioned, was a debtdue from the bank to the judgment debtor. The bank, the garnishee, appealedagainst the making of that attachment order because, they argued, if the bankcomplied with the attachment order in England the bank would remain liable, inBerlin, to pay that same sum to the judgment debtor that their London branchwould have paid to the judgment creditor. The bank succeeded in getting theattachment order set aside because the English court of appeal accepted, as amatter of international law, that payment in England, even pursuant to a courtorder, did not relieve the bank from the obligation to pay the debt in Berlin, whichexisted under the law in Berlin. It was, therefore, inequitable to have made theattachment order and leave the bank, the garnishee, liable to pay the sum twice.[10] The facts in that case are clearly distinguishable from the facts in this case. In thatcase the liability to pay twice would have been imposed on the bank, thegarnishee. Thus, it was the bank which resisted the attachment order because theywould be the ones who would have had to pay, in Berlin, the debt due to thejudgment debtor, the amount of which they would have paid already in England.In this case, the attachment order is for KEL, the garnishee, to pay a portion ofthe dividends to the respondents (including itself). KEL is clearly satisfied that ithas no obligation to pay the dividends to the beneficiaries as opposed to the7ibid.

appellant. Therefore, KEL is not concerned that it may have to pay, a second time,to the beneficiaries, the dividends it has been ordered by Worrell J to pay to therespondents. If there had been any such concern it would have been for KEL, thegarnishee, to raise. The appellant is in no position to complain of inequity orunfairness.Set off[11] The challenge of the appellant that the trial judge erred in ordering that KEL could‘set off’ the debt owed to it by the appellant against the dividends due from it tothe appellant deserves short shrift. This is seen immediately by substituting in thejudge’s order the word ‘withhold’ for the words ‘set off.’ The existence of therespective debts was never in issue. Nothing could have been simpler tounderstand than that KEL owed the appellant 749,692.50 in dividends and theappellant owed KEL 284,016.75 for costs. There has been no suggestion thatKEL was not entitled to withhold what the appellant owed to KEL, from whatKEL owed to the appellant. Indeed, the judge had no need to use the term ‘setoff’; he simply could have ordered that the dividends be attached with theobligation to pay the debt due to KEL.[12] Instead of guiding themselves by this straightforward proposition, the attorneysat law for the appellant chose to make submissions, even if faint, on the nature ofa set off and its unavailability in an application for attachment. It really was apointless exercise, because the appellant well knew that what entitled KEL towithhold the sum due to it was not the order of the trial judge. That order wassubstantially (and no more than) the judge’s acknowledgment and acceptance ofKEL’s right to the sum. What entitled KEL to withhold the sum owed to it wasthat KEL had a legal right to that sum, as a debt due and payable pursuant to acourt order. It was not a right conferred by the judge; it was a right that existed infact and in law. As stated, the judge could have simply attached the dividendswith payment of the debt due to KEL.[13] It makes no difference to consider counsel’s submission, that by making theattachment order the judge converted what was a mere withholding into the legal

vesting of the ‘set off’ sum in KEL. Even if that was accurate, the attachmentorder simply puts the ‘set off’ sum into the same category as the other sums forwhich the dividends were attached. It follows that this would be equally a matterfor the alleged beneficiaries to have challenged and not the appellant.[14] On both procedural grounds the appeal fails. This leaves for determination theconstitutional ground.The constitutional issues[15] It is distressing that the foundation of the appellant’s grounds of appeal, allegingthe infringement of constitutional rights and principles, is the excessive delay ofthe Court of Appeal in delivering the judgment that is now appealed to this Court.This Court has spoken out strongly against instances of this failure by our courtsin the past8 and there can be no doubting our stand on the matter of delay.Therefore, it is appropriate to address it with the restraint that is shown in theopinion of Saunders PCCJ, which deals with all aspects of the constitutionalgrounds, and with which I fully concur.JUDGMENT OF THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE SAUNDERS, PCCJ:[16]I endorse fully the judgment of Mr Justice Barrow and wish to add the followingon the issues relating to judicial independence and the separation of powers.Introduction[17]The relevant uncontested facts are that the Court of Appeal heard this case on25 May 2016 and pronounced its judgment some four years later. The hearingBench in 2016 comprised the Chief Justice, Mason JA, and Burgess JA.Madame Justice of Appeal Mason demitted office as a judge of the Court ofAppeal and assumed the post of Governor General of Barbados on 8 January2018. Burgess JA also resigned from the court in order to take up anappointment as a judge of this Court on 18 January 2019. The Court of Appeal’sjudgment was pronounced on 26 June 2020 and delivered to the parties on that8Singh v Attorney General [2018] CCJ 3 (AJ) at [60] – [61] and the cases cited in (n 26).

date. Apart from the Chief Justice’s signature, the judgment also bore thesignatures of Justices Mason and Burgess. Each of them concurred in thereasons and the result set out by the Chief Justice.Submissions of the Appellant[18]Mr Shepherd’s arguments on behalf of the appellant may be summarized in thefollowing way. Firstly, he submitted that the Court of Appeal’s judgment is anullity because the authority of the retired judges to act as appellate judges hadexpired and they had not re-taken the oath of judicial office before delivery ofthe judgment. He also stated that, as those judges were not present in court onthe 26 June 2020, the judgment was not delivered by a validly constituted Courtof Appeal. These points may be framed in the form of two questions: Was thejudgment a nullity because the retiring judges were not present in court on thedate the judgment was pronounced? Did they lack authority to concur in thejudgment?[19]Secondly, counsel rightly submits that the delivery of judgment is an essentiallyjudicial function and that the Constitution mandates that courts in Barbados beindependent and impartial.9It was suggested that, since, at the time thejudgment was delivered, the former Mason JA had become the GovernorGeneral, the Bench that gave the decision was not an independent and impartialtribunal as it then comprised the most exalted official of the Executive branchof government. This circumstance, it was said, created a breach of the separationof powers principle and it is now well established that courts will strike downor declare unconstitutional acts that amount to a breach of that principle.10Counsel urged the Court, on that account, to declare void the judgment givenby the Court of Appeal.9See s 18(8) of the Constitution of Barbados.Green Browne v R [2000] 1 AC 45; DPP v Mollison [2003] UKPC 6, (2003) 64 WIR 140; Griffith vR [2004] UKPC 58, (2004) 65 WIR 50; Scantlebury (Mormon) v R (2005) 68 WIR 88; The State vKhoyratty [2006] UKPC 13, [2007] 1 AC 80; BCB Holdings Ltd v The Attorney General of Belize [2013]CCJ 5 (AJ), (2013) 82 WIR 167; Zuniga v Attorney General of Belize [2014] CCJ 2 AJ, (2014) 84 WIR101; August v R [2018] CCJ 7 (AJ), [2018] 3 LRC 552.10

[20]In support of his arguments counsel cited several authorities including Orozcov The Attorney General,11 August v R,12 Hinds v The Queen,13 Ahnee v DPP,14The State v Khoyratty,15 DPP v Mollison,16 R v Home Secretary Ex p FireBrigades Union,17 R v Bow Street Magistrates Ex p Pinochet (No 2),18 andAttorney General of Guyana v Richardson.19Was the judgment a nullity? Did Mason JA and Burgess JA lack authority toconcur in the judgment?[21]The mode of delivery of judgment is governed partly by statute. Naturally, aslong as the judicial branch observes the statute, it is entitled itself to fill in anyapparent gaps. The relevant provisions of section 60 of the Supreme Court ofJudicature Act20 states:(1) (2) (3) On any appeal to the Court of Appeal, the judgment or opinion ofthe Court shall be pronounced as follows:a. If the President of the Court is taking part in the hearing ofthe appeal, by the President of the Court or such other Justiceof Appeal taking part in the hearing of the appeal as thePresident of the Court directs;b. (4) Any member of the Court of Appeal taking part in the hearing of anappeal may deliver a separate judgment or opinion concurring in ordissenting from the judgment or opiniona. of the Court; orb. of any other member of the Court taking part in the hearingof the appeal.[22]There was nothing done on 26 June 2020 that contravened this statute in theslightest. Nor was what done violative of any rule of court practice. It is routinefor judgments of the Court of Appeal to be pronounced and issued in the absence11[2020] 2 LRC 501.[2018] 3 LRC 552.13[1977] AC 195.14[1999] 2 AC 294.15[2006] UKPC 13. [2007] 1 AC 80.16[2003] UKPC 6. (2003) 64 WIR 140.17[1995] 2 AC 513.18[2000] 1 AC 119.19(2018) 92 WIR 416.20Cap 117A (Barbados).12

of a member of the hearing Bench

of these proceedings by Order of Dr the Hon Justice Olson Alleyne made on the 10th day of October 2018) AND APPELLANT JOHN VERE EVELYN DEANE FIRST RESPONDENT ERIC ASHBY BENTHAM DEANE Deceased, acting herein by RICHARD BASIL MARK DEANE duly substituted . Constitution of Barbados, Rev Ed 1971, Supreme Court of Judicature Act Cap 117A; Canada .