Transcription

STANFORD WOODS INSTITUTEFOR THE ENVIRONMENTResearch BriefTHE BILL LANE CENTER FORTHE AMERICAN WESTOCTOBER 2014Storing Water in California:What Can 2.7 Billion Buy Us?BackgroundCa l i for n i a’s w at er s y st em i s complex i n it sinfrastructural, fiscal, and governance landscape.Since 2000, state spending on water throughgeneral obligation bonds has provided about 27billion to fund California’s water supply, treatment,and infrastructure.1,a Authorized bond funds havesupported ecosystem enhancements (27%), floodprotection (25%), parks and public access (22%),integrated management (8%), drinking water quality(7%), water supply (6%), and stormwater and runoff(5%).2 Although state funding is a small percentage(3%) 3,b of total water expenditures in California, itis an important source of funding for many wateragencies.Proposition 1 — also known as the Water Quality,Supply, and Infrastructure Improvement Act of 2014 —is a bond on the November 4th ballot. If approved,Proposition 1 would provide 7.5 billion for water relatedinfrastructure projects. Of the 7.5 billion available, 2.7 billion — almost 40% — is targeted towards waterstorage (Figure 1). California has two options for waterstorage — surface water and groundwater storage —and both are eligible under Proposition 1.There is no single solution to increase the resilience ofCalifornia’s water system to manage climatic changeand increased growth. Nevertheless, finding ways tostore water during wet years, so that it is availableduring dry periods, is important for California if itis to increase its drought resiliency. The inclusionof water storage funds in Proposition 1 raises theimportant question: how should California spendits funds to store water? Although there has beena considerable amount of research on the costs andbenefits of surface water storage, there has not beenmuch analysis exploring the benefits and economiccosts of groundwater recharge and storage (GRS).To understand the benefits and economic costs of GRS,we mined post-2000 bond funding applications from fourpropositions (Figure 2). We examined how Californiahas used past bonds to implement GRS projects andAbout Water in the West and the AuthorsA j o i nt p r o g r a m of t h e S t a nf o r d Wo o d s In s t i t u te f o r t h eEnvironment and the Bill Lane Center for the American West,Water in the West focuses the resources of one of the world’spreeminent research institutions to address one of the mosturgent questions about the West’s future — how the region canacontinueCosts areconvertedinto 2014USD valueusingthe Construction Costto thrivedespitegrowingwaterscarcity.Index published by the Engineering-News Record.Debrais ais postdoctoralWaterin the West andbThisPerronepercentagefrom 2008-2011scholardata on forannualwater-relatedthe spendingDepartmentof Civil & Environmental Engineering at Stanfordin California.Water In The WestUniversity. Her research explores how the interactions amongwater, energy, and food resources affect decisions and tradeoffsinvolved in water resource management. (dperrone@stanford.edu)Melissa Rohde is a researcher for Water in the West and agraduate student in the Department of Civil & EnvironmentalEngineering at Stanford University. Her research focuses ongroundwater management in water-stressed regions.(mrohde@stanford.edu, www.melissarohde.com)1

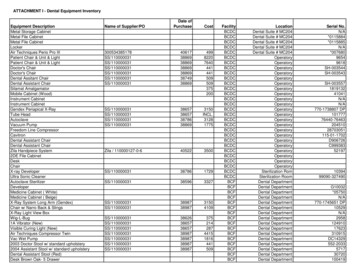

Research BriefFIGURE 1Proposition 1 Funding BreakdownFIGURE 2Proposition TimelineFloods ( 395M)Drinking water ( 520M)Drought Preparedness ( 810M)PROPOSITION 13Groundwater Rechargeand Storage2000PROPOSITION 50Water Quality Supply andSafe Drinking Program190 / 190GRS ApplicationsSubmitted200112 / 25GRS ApplicationsSubmitted62 / 190GRS Applications Awarded200211 / 12GRS Applications Awarded 313M / 313MFunds Awarded to GRS2003 252M / 451MFunds Awarded to GRSWater Storage ( 2.7B)Water Recycling ( 725M)Groundwater ( 900M)Watershed Protection ( 1.5B)answered some key questions: What are the proposedcosts of GRS projects? Is GRS an integrative andversatile water management technique? Which GRSapplications are successful in receiving bond funds?This effort is the most comprehensive analysis of GRScosts in California to date.PROPOSITION 1EDisaster Preparationand Flood Protection200419 / 52GRS ApplicationsSubmitted200510 / 19GRS Applications Awarded2006 96M / 286MFunds Awarded to GRS2007PROPOSITION 84Safe Drinking Water,Water Quality and Supply,Flood Control27 / 71GRS ApplicationsSubmitted19 / 27GRS Applications Awarded 193M / 355MFunds Awarded to GRSKey Findingswastewater, or a blend — can influence GRS costs(Figure 3d).The costs c of groundwater recharge and storageprojects vary considerably, rangingd between 100and 1,200 per acre-foot, with a median of 400 peracre-foot. These numbers (Figure 3a) are basedGroundwater recharge and storage costs are aboutthree times smaller when the primary purpose isto recharge and store groundwater only. Costs areon proposed project costse for both accepted anddeclined applications. The costs to produce (throughwastewater treatment or decentralized stormwatercapture) or purchase (from the state water project orother sources) water are not included. Nevertheless,there are multiple factors that influence the range inGRS project costs (Figure 3a-d). For example, thetype of water used — surface water, stormwater,cCosts are converted into 2014 USD value using the Construction CostIndex published by the Engineering-News Record.dPresented as the 25th and 75th percentile range.eProject costs include: land; planning, design, and engineering;capital; administration; environmental compliance, mitigation, andenhancement; construction administration; and contingency.Water In The Westhigher when GRS is used as a co-benefit to otherwater projects (Figure 3b). Co-benefits include, butare not limited to, water quality improvements, floodcontrol, wildlife enhancement, and seawater intrusionprevention.About 40% of the groundwater recharge and storageapplications submitted for bond funds were awarded.High and medium priority groundwater basinsrepresent more than 90% of project applicationsfor bond funding. High and medium priority basinsrepresent only 25% of groundwater basins in California,but more than 95% of California’s groundwaterpumping.4 The basin prioritization system is the state’sstrategy for allocating its limited funding to monitor2

Research BriefFIGURE 3Ranged of Groundwater Recharge and Storage Costsa) All ApplicationsMedianAllb) By MotivationPrimary GRS ProjectsCo-benefit GRS Projectsc) By PropositionProposition 1EProposition 13Proposition 50Proposition 84d) By Type of WaterSurface 3000Annual Cost Per Volume — 2014 USD / Acre-Footand manage sustainable groundwater use. Althoughpast funding is concentrated in areas with the highestneed, there is a demand for GRS that is not being metby state bond funding.Discussing California’s WaterStorage OptionsCalifornia gets money and water in the bank withgroundwater storage. The 2014 water bond hasfor surface water storage, that amount could fundapproximately 1.4 million acre-feet of new surfacestorage capacity. Conversely, if the 2.7 billion fromProposition 1 earmarked for water storage wereto be spent on GRSg, California could gain about8.4 million acre-feet of new groundwater storagecapacity (Figure 4). For the same amount of money,groundwater storage could provide about six timesmore storage capacity than surface water storage.earmarked 2.7 billion for water storage projectsthat improve the state water system, serve publicbenefits, and are cost-effective. Assuming thatsurface and groundwater storage projects meet thecriteria to serve public benefits, how much surfaceand groundwater storage can California get with 2.7billion? Using a median cost of 1,900 per acre-foot5,fLuis Reservoirs.fThis median cost was calculated based on the capital costs and newstorage capacity for eligible reservoir projects: building Temperanceand Sites Reservoirs, and expanding Shasta, Los Vaqueros, and SanWater In The WestgThis was calculated using 320 per acre-foot as the median GRScost for projects with the primary purpose to recharge and storegroundwater (see Figure 3b).3

Research BriefFIGURE 4How Much Storage Can You Get With 2.7B?8.4Million Acre-Feetis only 70% of the total.6 With unused surface waterreservoir space and increasing groundwater spacedue to overdraft, it is not the size of the reservoir thatis the issue, but the availability of water to fill it.The decentralized configuration of GRS allows localwater managers to take advantage of a diversifiedwater portfolio. Most of the popular surface waterstorage projects in consideration for the 2.7 billionwater storage funds would be managed centrally,reducing supply and demand flexibility.1.4Higher priority basins are getting bond funds, butthe overall demand for bond funds is unmet. GRSMillion Acre-Feetprojects are proposed primarily in higher prioritybasins. Although past bond funds are concentratedin the areas with the highest need, a demand in GRSprojects remains throughout California and is notbeing met by past state bond funds.New Surface WaterStorage CapacityNew GroundwaterStorage CapacityGroundwater recharge and storage projects can serveas an integrative and versatile water managementtool. When GRS is used as a co-benefit to other waterprojects, costs are higher but benefits are greatertoo. Past bond applications show that communitiesare integrating GRS into flood control, stormwatermanagement, and wastewater recycling projects.Doing so can augment California’s water supply, bufferrisk, and serve local water management objectives.A diversified water portfolio would provide a morecontinuous supply of water that is subject less toseasonal and interannual variability. Unlike surfacewater, which is influenced largely by the Sierrasnowpack, wastewater is produced continuously inurban centers. Although wastewater may be a feasibleoption only for population centers, the impacts ofenhancing local self-sufficiency will be felt statewidebecause California’s water system is interconnected.As California’s water resources become subject toclimatic change, a diversified water portfolio cangive water managers an adaptive edge. California’s154 major surface water reservoirs currently have astorage capacity of approximately 40 million acrefeet, and the historical average use of that capacityWater In The WestConclusionOur analysis of how California has used past bonds toimplement GRS projects reveals that: Groundwater recharge and storage is more costeffective than surface water storage. Groundwater recharge and storage can serve asa versatile water management tool and promote adiversified water portfolio. Past bond funding is concentrated in areas withhigher basin prioritizations, and a demand ingroundwater recharge and storage projectsremains unmet through state bond funds.These findings suggest that groundwater rechargeand storage can play an important role in managingCalifornia’s water resources in the future.4

Research BriefReferences1. Legislative Analyst’s Office. 2009. Financing Water Infrastructure.Sacramento, California. Available at ncing Water Infrastructure 82609.pdf2. Chappelle, C., A. Fahlund, E. Freeman, B. Gray, E. Hanak, K. Jessoe, J.Lund, J. Medellín-Azuara, D. Misczynski, D. Mitchell, J. Nachbaur, R.Suddeth. 2014. Paying for Water in California, Technical AppendixC (Table C2). San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California.3. Hanak, E., B. Gray, J. Lund, D. Mitchell, C. Chappelle, A. Fahlund, K.Jessoe, J. Medellín- Azuara, D. Misczynski, J. Nachbaur, R. Suddeth.2014. Paying for Water in California (Table 1). San Francisco:Public Policy Institute of California.4. California Department of Water Resources. 2014. CASGEM BasinPrioritization. Available at http://water.ca.gov/groundwater/casgem/basin prioritization.cfm5. Lund, J. 2014. Should California expand reservoir capacity by removingsediment? Available at diment6. California Department of Water Resources. 2014. Summary of Storagein Major Reservoirs as of September 30, 2014. Available at SUMJerry Yang & Akiko Yamazaki Environment & Energy BuildingMC 4205 / 473 Via Ortega, Stanford, CA d.eduEmailenvironment@stanford.edu

Discussing California's Water . Storage Options. California gets money and water in the bank with groundwater storage. The 2014 water bond has . earmarked 2.7 billion for water storage projects that improve the state water system, serve public benefits, and are cost-effective. Assuming that surface and groundwater storage projects meet the