Transcription

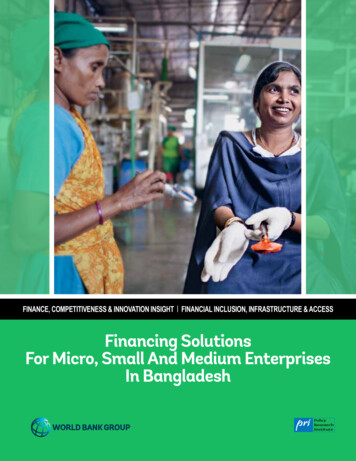

FINANCE, COMPETITIVENESS & INNOVATION INSIGHT FINANCIAL INCLUSION, INFRASTRUCTURE & ACCESSFinancing SolutionsFor Micro, Small And Medium EnterprisesIn Bangladesh

2019 The World Bank Group1818 H Street NWWashington, DC 20433Telephone: 202-473-1000Internet: www.worldbank.orgAll rights reserved.This volume is a product of the staff and external authors of the World Bank Group. The World BankGroup refers to the member institutions of the World Bank Group: The World Bank (InternationalBank for Reconstruction and Development); International Finance Corporation (IFC); andMultilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), which are separate and distinct legal entitieseach organized under its respective Articles of Agreement. We encourage use for educational andnon-commercial purposes.The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflectthe views of the Directors or Executive Directors of the respective institutions of the World BankGroup or the governments they represent. The World Bank Group does not guarantee the accuracyof the data included in this work.Rights and PermissionsThe material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this workwithout permission may be a violation of applicable law. The World Bank encourages disseminationof its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly.All queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Officeof the Publisher, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA;fax: 202-522-2422; e-mail: pubrights@worldbank.org.Cover Photo: Gazi Nafis Ahmed/ IFC. Insides Photo Credits: World Bank and IFC Photo Libraries

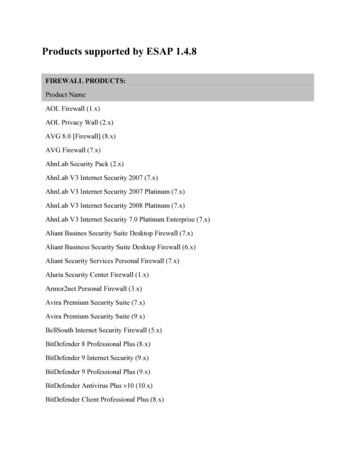

FINANCE, COMPETITIVENESS & INNOVATION INSIGHT FINANCIAL INCLUSION, INFRASTRUCTURE & ACCESSTABLE OF CONTENTSABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMSVACKNOWLEDGMENTSVIIEXECUTIVE SUMMARYIXI. MSMES: IMPORTANCE AND FINANCING CONSTRAINTSIntroductionMSMEs in BangladeshClassificationStructure and RoleThe Financing ChallengeMSME financing constraintsFormal Credit Supply for MSMEsEstimated Financing Gap for MicroenterprisesEstimated Financing Gap for SMEsII. MSME POLICY, FINANCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE GAPS AND ALTERNATIVE SOLUTIONSThe Regulatory and Financing PoliciesInstitutional CoordinationRegulatory PoliciesFinancing Policies and SchemesEffectivenessPolicy RecommendationsThe Financial Infrastructure GapsCredit ReportingSecured Transactions and Collateral RegistriesInsolvency and Debt ResolutionPayment SystemsPolicy RecommendationsExploring Innovative and Alternative Financing OptionsRisk-sharing FacilitiesAlternative financial instrumentsFintech SolutionsPolicy RecommendationsIII. 2931FINANCING SOLUTIONS FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES IN BANGLADESHI

ANNEXESAnnex 1. Definition and Classification of MSMEsAnnex 2. MSME Structure and Roles (2013 Bangladesh Economic Census)Annex 3. Estimation of the Small Enterprise Financing Gap Using Bangladesh BankLoan DataAnnex 4. Roles and Activities of Agencies Supporting MSMEsAnnex 5. General Principles for Credit Reporting SystemsAnnex 6. Principles for Credit Guarantee Schemes for SMEsAnnex 7. Fintech LIST OF BOXESBox 1: An Approach Framework to State Intervention and State-owned BanksBox 2: MSME Segmentation and Prospects from a Bank’s PerspectiveBox 3: Lessons of Positive Adaptive ExperiencesBox 4: India’s Experience with Private Sector-led CIBsBox 5: International Examples of Successful Secured Transaction ReformsBox 6: Credit Guarantee Schemes in India and ThailandBox 7: The United States Small Business Investment Company (SBIC)Box 8: Kenya’s Success with Fintech companiesBox 9: General Principles for Credit Reporting Systems (CRS)Box 10: Recommendations for Effective Oversight12151719202426283940LIST OF FIGURESFigure 1: Distribution of EmploymentFigure 2: Average Labor Productivity 2013 (Tk 000)Figure 3: Microcredit Members, June 2016 (million)Figure 4: Distribution of Membership by Gender (%)Figure 5: Loans Disbursed, June 2016Figure 6: Average Loan Size, June 2016Figure 7: Expansion of Banking Sector MSME Lending (Tk billion)Figure 8: Distribution of Formal MSME Credit by Economic Activities, June 2016 (%)33555566LIST OF TABLESTable 1: Financial Inclusion Indicators, by Country, South AsiaTable 2: Unified MSME Definition Adopted under the 2016 Industrial PolicyTable 3: MSME Loans Outstanding as a Share of Total LoansTable 4: Average Demand for Loans Among MicroenterprisesTable 5: Loan Supply for Microenterprises, June 2016IX2677TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table 6: IFC Estimates of Financing Gap, 2011 versus 2017Table 7: State Intervention RationalesTable 8: SOFI Institutional TypologiesTable 9: SOFI Instrument TypologiesTable 10: Efficiency of the Bangladesh Regulatory Regime, 2018 — Getting CreditTable 11: Definition of MSME in the 2003 Economic CensusTable 12: Definition of MSMEs in the Bangladesh 2010 Industrial PolicyTable 13: Bangladesh Bank Definition of Small EnterprisesTable 14: Updated Definition of MSMEs by the Bangladesh Bank, 2016Table 15: Size and Employment of Enterprises in Bangladesh, 2013Table 16: Distribution of Enterprises by Major Economic Activities, 2013 (numbers in 000)Table 17: Banking Sector Loan Disbursements to SMEsTable 18: Small Enterprise Financing Gap8131314183333343435353536FINANCING SOLUTIONS FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES IN BANGLADESHIII

IVSECTION TITLE

FINANCIAL LONG-TERMFINANCE, COMPETITIVENESSFINANCE, COMPETITIVENESS& INNOVATION INANCE & ACCESSABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMSADBAsian Development BankADRAlternative Dispute ResolutionBACHBangladesh Automated Clearing HouseBASICBank for Small Industries and CommerceBBSBangladesh Bureau of StatisticsBFIDBank and Financial Institutions Division (Ministry of Finance)BIACBangladesh International Arbitration CenterBPCBusiness Promotion CouncilBSCICBangladesh Small and Cottage Industries CorporationIBCredit Information BureauCGSCredit Guarantee SchemeCIBCredit Information BureauCICCredit Information CompaniesCRSCredit Reporting SystemDFSDigital Financial ServicesECGSExport Credit Guarantee SchemeEFTElectronic Funds TransferEGBMPEnterprise Growth and Bank Modernization ProjectFCIFinance, Competitiveness, and InnovationFIRSTFinancial Sector Reform and Strengthening Initiative (World Bank)FSPDSMEFinancial Sector Project for the Development of Small and MediumSized EnterprisesFYFiscal YearGDPGross Domestic ProductICTInformation and Communication TechnologiesIDLCIndustrial Development Leasing CompanyIFCInternational Finance CorporationIFIInternational Financial InstitutionInMInstitute for Inclusive Finance and DevelopmentJCAPJoint Capital Markets InitiativeJICAJapan International Cooperation AgencyFINANCING SOLUTIONS FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES IN BANGLADESHV

VIJPYJapanese YenLFSLabor Force SurveyMFIsMicrofinance InstitutionsMFSMobile Financial ServicesMOIMinistry of IndustryMRAMicro-Credit Regulatory AuthorityMSMEMicro, Small and Medium EnterprisesNBFINon-bank Financial InstitutionNGONon-governmental OrganizationNPLNon-Peforming LoanNSDCNational SME Development CouncilOECDOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and DevelopmentPFIPartner Financial InstitutionsPRIPolicy Research InstituteR&DResearch and DevelopmentRMGReady-made GarmentRSFRisk-Sharing FacilitySBASmall Business AdministrationSBICSmall Business Investment CompanySCISmall and cottage industrySEFSmall Enterprise FundSMEsSmall and Medium EnterprisesSMEDPThe Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Development ProjectSMEFSME FoundationSMESDPSmall and Medium Enterprise Sector Development ProjectSOBState-owned banksSOFIState-owned financial institutionSTRSecured Transaction LawTkBangladeshi takaTSLTwo-Step LoanUKUnited KingdomUSAIDUnited States Agency for International DevelopmentUS United States DollarVCVenture CapitalWBGWorld Bank GroupACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

FINANCE, COMPETITIVENESS & INNOVATION INSIGHT FINANCIAL INCLUSION, INFRASTRUCTURE & ACCESSACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis report was prepared by the World Bank’s Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation (FCI)Global Practice team, led by Mihasonirina Andrianaivo (Senior Financial Sector Specialist),Ilias Skamnelos (Lead Financial Sector Specialist) and Aminata Ndiaye (Financial SectorSpecialist).It is based on the findings of a report produced bythe Policy Research Institute (PRI) of Bangladesh,with inputs from the World Bank, including adesk review and a field mission in August 2017.The data collection, analysis, and interviews withgovernment officials and stakeholders, as wellas the formulation of policy recommendations,were made possible thanks to the dedication anddiligence of Sadiq Ahmed and his team at PRI.The report was prepared as a sub-task of theBangladesh Financial Sector DevelopmentProgrammatic Approach. The team is grateful forthe overall guidance and advice of its Task TeamLeader Korotoumou Ouattara (Senior FinancialSector Specialist). This report owes much toSimon Bell (Global Lead for SME finance) wholed an initial knowledge-sharing mission with theBangladesh authorities and provided guidance andfeedback on earlier versions of the work.Inputs were provided by Ananya Kader (SeniorFinancial Sector Specialist), Colin Raymond(Lead Financial Sector Specialist), Nina PavlovaMocheva (Senior Financial Sector Specialist),Murat Sultanov (Senior Financial SectorSpecialist), Ashutosh Tandon (Financial SectorSpecialist) and Muhammad Mustafizur Rahman(Consultant). The report also benefited from theguidance of Harish Natarajan (Lead FinancialSector Specialist), Shah Nur Quayyum (SeniorFinancial Sector Specialist) and A.K.M. Abdullah(Senior Financial Sector Specialist).The team is also grateful to the peer reviewers,including Ghada O. Teima (Lead FinancialSector Specialist) and Alper Ahmet Oguz (SeniorFinancial Sector Specialist) for their valuablecomments.The team would like to express its particularappreciation to Qimiao Fan (Country Director,Bangladesh), Esperanza Lasagabaster (PracticeManager, FCI South Asia region) and ChristianEigen-Zucchi (Program Leader, Equitable Growth,Finance and Institutions [EFI]) for their overallguidance and review. The team would also liketo thank all government officials and stakeholderswho patiently responded to interview questions.We also thank Aichin Lim Jones for design andproduction services, Barbara Balaj for editorialsupport, as well as Vanda Melecky and Aza Rashidfor their operational support.Note: This paper summarizes the main outcomes of a survey that received responses from 10 countries. Because of confidentiality restrictions, the country specific results have been made anonymous in the present reportFINANCING SOLUTIONS FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES IN BANGLADESHVII

VIIIACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

FINANCE, COMPETITIVENESS & INNOVATION INSIGHT FINANCIAL INCLUSION, INFRASTRUCTURE & ACCESSEXECUTIVE SUMMARYImproving access to finance for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) is afundamental challenge at the heart of a country’s financial and economic development;debates continue over the design and effectiveness of MSME policy. This report presents a deskreview of the financing gap, constraints and policies related to the MSME financing in Bangladesh.It aims to provide relevant policy recommendations at a critical time when past policies can beobjectively evaluated, and as innovative and alternative instruments emerge, thereby presenting as aunique opportunity to address these financing challenges.Despite significant knowledge gaps, MSMEsare undoubtedly the backbone of non-farm jobcreation in Bangladesh. The country lacked auniform MSME definition until the 2016 IndustrialPolicy. It now needs to promote this as a unifieddefinition at the policy level, while also improvingrelevant data collection and analysis. Nevertheless,the 2013 Economic Census and Enterprise Surveyof the same year provide important insights. Some99 percent of all non-farm enterprises fall into themicro and small enterprises categories, providingemployment to 20.3 million Bangladeshis workersin 2013. Most of these enterprises are informal andfocus primarily on trading activities. As such, theyface a substantial productivity challenge. Women’seconomic participation lags expectations given thecountry’s current development stage.Access to formal finance by MSMEs is limitedcompared to the average for the South Asiaregion, with an estimated financing gap ofBangladeshi Taka (TK) 237 billion (US 2.8billion). Small and medium firms perceive accessto finance as the third most important obstacle. Inline with its Vision 2021, the government has soughtto improve MSMEs’ access to finance throughmultiple channels. Bangladesh is famous forpioneering the global micro-credit revolution basedon group guarantees and the total banking sectorlending to MSMEs almost tripled from 2010 to2016. Nevertheless, there still appears to be a sizablefinancing gap for MSMEs, estimated at TK 237billion (US 2.8 billion) (building on InternationalFinance Corporation [IFC] calculations).While recognizing the multi-sectoral challengeof MSME policy making, improvements instrategic vision and coordination can yieldsignificant results to MSME developmentand finance. MSME policy invariably involvesseveral agencies. However, there is currently littleinstitutional coordination and no strategic vision oroverarching policy framework. Among a multitudeof agencies, the Ministry of Industry has takenan active role in MSME development, and theBangladesh Bank has led MSME finance policy,including direct interventions such as refinancingwindows. Based on international experience,Bangladesh would benefit from establishing acentral coordinating, multi-party body to promoteMSME development and finance.The Bangladesh Bank’s efforts appear to haveincreased MSME financing overall from a lowbase; however, its impact and effectiveness couldbe enhanced by reviewing past and presentfinancing schemes and institutions. Most of thesuccess has been with medium enterprises thatdo not necessarily face the strongest financingconstraints — and most of the financing is shortterm in nature. The Bangladesh Bank shouldrefocus its attention on the most constrained amongthe MSMEs. In addition, the Bangladesh Bank’spolicy emphasis on banks does not appear to befully internalized. Indeed, the banks’ response canbest be characterized as one of passive compliance.The reasons appear to be based on persistentunderlying financial infrastructure weaknesses andbanks’ risk perceptions. Nevertheless, success casesFINANCING SOLUTIONS FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES IN BANGLADESHIX

such as Brac Bank, the Industrial DevelopmentLeasing Company (IDLC), and Prime Bankdeserve some credit. The Bangladesh Bank wouldbenefit from undertaking an evaluation of pastschemes, guidelines and success stories to informfuture MSME finance policies. Lastly, state-ownedfinancial institutions, which would traditionallysupport MSME development, are faced withsignificant challenges – notably with regard totheir mandate and governance, profitability, capitaladequacy, and non-performing loans. It is importantthat the government clarifies the long-term goals,mandates and objectives of the state-ownedfinancial institutions, and undertakes the necessaryreforms to enhance their role.There are significant financial infrastructureweaknesses that need to be addressed to encouragemarket-driven MSME financial inclusion. The2018 World Bank Group’s Doing Business surveyranks Bangladesh at 159 (of 190 countries) forthe ‘Getting Credit’ indicator, a measure of creditinformation sharing and legal rights of borrowersand lenders. In future, the credit bureau coverageshould include all commercial loans, regardlessof value. It should also mine all available data tostrengthen MSME credit information. Furthermore,loans are primarily secured through property-basedcollateral (that face a challenge regarding propertyrights), whereas movable collateral is not yetaccepted for secured lending. Therefore, MSMEfinancing would benefit from the expansion of theregistry’s mandate to include movable collateral,the enactment of the Secured Transactions Lawand the creation of a register. Notwithstandingseveral legal avenues in place, insolvency anddebt resolution are, in practice, very difficult andcostly. A Small Claims Court could lead to fasteradjudication with lower costs for cases relating toMSMEs. In this regard, it is important to codify andoperationalize mediation within the Money LoanCourts and the general courts. To settle disputesinvolving small claims or recovering loans to smallenterprises, the Small Cause Courts Act will requireamendments. Institutionalizing Alternative DisputeResolution (ADR) mechanisms for commercialdispute settlement could also help address contractenforcement processes.XEXECUTIVE SUMMARYPayment systems, in particular, hold promisein expanding MSME financial access throughDigital Financial Services (DFS). Technologyis transforming the global economy and MSMEfinancing. Several enabling factors are critical tosuccessfully galvanizing this technology, and theregulatory environment is particularly important.The Bangladesh Bank has made significantadvances toward the adoption of a digitizedpayment system, and has encouraged mobilefinancial services. The rapid growth of informationand communication technologies (ICT) serviceshas led to the increasing use of technology for thedelivery of financial services, but penetration islimited. Among the key challenges, the legal andregulatory structure of the mobile-payments systemis restrictive by only allowing for a bank-led model.The goal should be to transform this into a mobilefinancial system with a broader range of financialservices. Therefore, the Bangladesh Bank needsto review its strategy and policy relating to DFS,including making the eco-system more supportivefor the growth of Fintech.Several innovative and alternative financingoptions can be further explored, including risksharing facilities (RSFs), factoring, warehousereceipt finance, and/or start-up capital policies.RSFs can partially cover the risks of MSME lendingand help de-risk lending decisions by commercialbanks. Bangladesh can launch a MSME-focusedscheme that learns from its past experiences,specifically by addressing governance concerns.In addition, a range of pre-bank financing optionshas emerged to support young and dynamic firms.However, the requisite enabling environment isstill under development. As financial infrastructureimproves and digital technology develops, assetbased solutions — such as factoring and warehousereceipt financing — are likely to become moreattractive. Finally, start-up capital is much needed,but still missing. In this regard, public policy canhelp to reduce the risks associated with this segment.Table 1 provides a summary of key recommendationsfound in this report.

Table 1: Financial Inclusion Indicators, by Country, South AsiaShort-termMedium-termInstitutionsPromote the use of a unified definition at the policy level and improvedata collection and analysis. Establish a multi-party, central coordinating body to promote MSMEdevelopment and financing. Undertake an evaluation of past schemes and Bangladesh Bankguidelines to inform future MSME finance policies.H Refocus attention on the most constrained among the MSMEs – the‘missing middle’.a Clarify the long-term goals of the government and the mandates andobjectives of state-owned financial institutions and undertake therequisite reforms.H InfrastructureImprove the credit information infrastructure, expanding the reach ofthe credit information bureau.H Enact the Secured Transaction Law and create a register. Establish a Small Claims Court and institutionalize ADR mechanisms. InnovationPromote an effective payment system and financial infrastructure tosupport the rollout of DFS and the evolution of Fintech.H Pursue the necessary legal and infrastructure needs for theintroduction or expansion of alternative finance.H Introduce a Risk-Sharing Facility for SMEs. Note: ADR Alternative Dispute Resolution; DFS Digital Financial Services; MSME micro-, small and medium enterprises;SME small and medium enterprises.H High priority reform. Short-term is within 9 months, and medium-term is within 18-24 months.aThe ‘missing middle’ refers to small firms and firms at the low-end of the medium-sized enterprise segment that have themost difficulty in accessing bank finance.FINANCING SOLUTIONS FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES IN BANGLADESHXI

XIISECTION TITLE

FINANCE, COMPETITIVENESS & INNOVATION INSIGHT FINANCIAL INCLUSION, INFRASTRUCTURE & ACCESSI. MSMES: IMPORTANCEAND FINANCING CONSTRAINTSIntroductionDespite limited data, micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) are undoubtedlythe backbone of non-farm job creation in Bangladesh. Some 99 percent of all non-farmenterprises fall within the micro and small enterprise categories, providing employment to20.3 million Bangladeshi workers in 2013. Yet, the use of formal finance by small firms is limitedcompared to the South Asia average, with an estimated MSME financing gap of Bangladeshi TakaTk 237 billion (US 2.8 billion).1Improving MSME access to finance is afundamental challenge at the heart of acountry’s financial and economic development.Development theory emphasizes the role offinance in achieving growth and income equality.However, one of the most important issues facingMSMEs is their difficulty in accessing finance.Given market imperfections, the role of statepolicy is critical — from promoting an enablingenvironment to more active market interventions.This report presents a desk review of thefinancing gap, constraints and policies relatedto the MSME financing in Bangladesh.2 Indoing so, it aims to provide relevant policyrecommendations at a critical time when pastpolicies can be objectively evaluated, and asinnovative and alternative instruments areemerging, thereby presenting a unique opportunityto address these financing challenges.Section A outlines the structure and role ofMSMEs in the economy of Bangladesh, as well astheir financing constraints. Section B.1 turns to theregulatory and financing policies pursued by theauthorities, examining coordination challengesand the effectiveness of efforts toward formulatingkey recommendations. Section B.2 focuses onthe challenges and recommendations in the realmof financial infrastructure, specifically creditreporting, secured transactions and collateralregistries, insolvency and debt resolution, andpayment systems. Section B.3 outlines innovativeand alternative financing options for MSMEs,including risk-sharing facilities, asset-basedsolutions, and Fintech (financial technology).Finally, Section C concludes with an overview ofkey findings from the report.MSMEs in BangladeshClassificationBangladesh has lacked a uniform MSMEdefinition, which has resulted in fundamentalknowledge gaps,3 as well as an inability toquantify the impact of government and donorfinancial assistance. There have been multipledefinitions deployed since 2003 (see annex 1),including by the Economic Censuses conductedby the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS),the Bangladesh Industrial Policy, and surveys byinternational organizations, such as the WorldBank Group’s (WBG) Enterprise Surveys. Somespecial-purpose sample surveys have also beenused occasionally to diagnose constraints, albeitin a limited manner.The MSME definition set by the 2016 IndustrialPolicy is now broadly accepted as a unifieddefinition at the policy level. It is based on thevalue of fixed assets (excluding land and buildings)and/or the number of employees (see table 2). Thisunified national definition should be followed byall government entities. Notably, the BangladeshBank has updated its definition accordingly (seeannex 1).FINANCING SOLUTIONS FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES IN BANGLADESH1

Table 2: Unified MSME Definition Adopted under the 2016 Industrial PolicyType of IndustryAmount of Investment in Tk (ReplacementCost and Value of Fixed Assets, excludingLand and Factory Buildings)Number ofEmployedWorkersCottage IndustryBelow 1 millionMaximum 15Micro Industry1 to 7.5 million16-307.5 to 150 million31-1201 to 20 million16-50Manufacturing150 to 500 million121-300Service20 to 300 million51-120Small IndustryMedium IndustryManufacturingServiceSource: National Industrial Policy, Government of Bangladesh, 2016.Structure and RoleDespite the absence of consistent data overtime, there are still some useful conclusionsthat can be drawn, primarily from the 2013Government Economic Census and the EnterpriseSurvey (World Bank 2013).MSMEs are the backbone of non-farm jobcreation in Bangladesh (which is broadly inline with other countries in the region). The 2013Economic Census counts a staggering 7.8 millionenterprises, of which almost 89 percent belong tothe cottage and microenterprise segment, and 11percent to the small enterprise segment. Some 99percent of all non-farm enterprises fall into themicro and small segments, providing employmentto 20.3 million in 2013. As such, this makesthem the largest source of employment apart ofagriculture (figure 1) — and a key contributorto poverty reduction. The MSME sector overallprovides 86 percent of total employment outsideof agriculture and the public sector. Notably,the 2013 Labor Force Survey (LFS) showsthat informal employment in services andmanufacturing accounted for almost 87 percent oftotal employment. (Table 11 in annex 2 provides anoverview of the size distribution and employmentdata for 2013.)Most of these enterprises are informal, that is,they are not registered with the government.Informality is prevalent in the private economy2and especially among small firms. Some 90 percentof microenterprises and 95.5 percent of smallenterprises are engaged in providing informalservices for the domestic market. The average sizeof these firms — while slightly increasing — isstill low, at 4 employees in urban areas, and evenlower in rural areas. There is limited value chainintegration among this enterprise segment, andnegligible contribution to the export market.The MSME sector, in particular micro andsmall enterprises, is dominated by tradingactivities. The distribution of enterprises by broadeconomic activities and size (table 12 in annex 2)reveals that more than 87 and 94 percent of themicro and small enterprises, respectively, areengaged in non-manufacturing services, mostly intrading. However, medium and large enterprisesare heavily involved in industrial activities,with almost 50 and 53 percent of the mediumand large enterprises, respectively, involved inmanufacturing activities. Reorienting the SMEsector away from trading to higher value-addedeconomic activity remains an important challenge.The productivity challenge for micro and smallenterprises is substantial. Evidence from themanufacturing sector suggests that the micro andsmall enterprises tend to have low value-added perworker and low average wages. Figure 2 showsthat the average labor productivity in micro andsmall manufacturing is barely above the lowproductivity of the agriculture sector.I. MSMES: IMPORTANCE AND FINANCING CONSTRAINTS

The Financing ChallengeFigure 1: Distribution ofEmployment (%)50MSME financing therNon-FarmSource: BBS, LFS 2013 and Economic Census 2013.Figure 2: Average LaborProductivity 2013 (Tk 000)Total196Services323SS Manufacturing77LS Manufacturing352Agriculture710100200300400Note: LS Large Scale. SS Small Scale.Women’s participation in economic activity lagsbehind most low-income countries according tothe 2013 Enterprise Survey. The share of womenin ownership and management is less than halfthat of low-income countries across all firm sizes.Although women’s participation in the workforceis higher (16 percent), especially for larger firms,it is still significantly lower than the average (34percent) and that of low-income countries (25percent).Small firms’ use of formal finance is limitedcompared to larger firms, as well as incomparison with the average for the South Asiaregion. The 2013 Enterprise Survey estimates thatonly 27.5 percent of small firms have bank loans/lines of credit compared to 44 percent of large firmsand 30 percent observed in the region. Small firmsrely more on internal funds to finance investments.They face higher collateral level requirementsrelative to the value of loans received.Small and medium firms perceive access tofinance as the third most important obstacle inthe business environment. According to the 2013Enterprise Survey, all firms perceive politicalinstability and electricity as the top obstacles tothe business environment. Unlike smaller firms,large firms rank corruption — not access tofinance — as the third most important obstacle.Notably, there appears to be a segment, known asthe ‘missing middle’, of small firms and firms atthe low-end of the medium-sized enterprises thathave the most difficulty in accessing bank finance.Financial constraints faced by MSMEs inBangladesh are widely recognized in the academicliterature and other studies.4 The 2017 InternationalFinance Corporation (IFC) SME Finance Gap Studyobserved that 55 percent of all MSMEs reportedat least being partially financially constrained, ofwhich 39 percent reported being “fully constrained”.Daniels (2003) reported the availability of financingas the top problem faced by MSMEs (based ona nationwide survey of private enterprises), withlimited credit from formal sources. In another study,Alam and Ullah (2006) also identified the lack ofmedium to long-term credit among the reasons forslow growth among MSMEs. Likewise, Haider andAkhter (2014) found that 50 percent of

Annex 3. Estimation of the Small Enterprise Financing Gap Using Bangladesh Bank Loan Data 35 Annex 4. Roles and Activities of Agencies Supporting MSMEs 37 Annex 5. General Principles for Credit Reporting Systems 39 Annex 6. Principles for Credit Guarantee Schemes for SMEs 40 Annex 7. Fintech Solutions 41 REFERENCES 37 ENDENOTES 45 LIST OF BOXES