Transcription

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIESEPPP DP No. 2014-06Public Private Partnerships andEfficiency: A Short AssessmentAntonio Estache et Stéphane SaussierJuillet 2014Chaire Economie des Partenariats Public-PrivéInstitut d’Administration des Entreprises

Public Private Partnerships and Efficiency:A Short AssessmentAntonio EstacheEuropean Centre for Advanced Research in Economics and Statistics (ECARES)Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB)&Stéphane SaussierSorbonne Business SchoolUniversity Paris I Panthéon-SorbonneIntroductionOver the last 35 years or so, governments around the world have enhanced the participationof private actors to deliver a wide variety of goods and services, traditionally delivered by thepublic sector.The development of public–private partnerships (PPPs) has been, andcontinues to be, one of the most popular contractual forms this increased private sector rolehas taken. Despite this long lasting interest, robust theoretical and empirical research on theirefficiency has, however, only emerged relatively recently.Theoretical frameworks designed to tackle “make or buy” issues and contracting strategiesbetween private firms may have provided some of the clearest insights into issues related tocontracting with government. To many economists, PPPs may indeed be seen as a simpleextension of vertical disintegration or contracting out by governments (de Bettignies & al2009). But many also recognize that the political dimensions of PPPs urge for theoreticaladaptations to get a fuller sense of the drivers of their efficiency (Spiller, 2009; Williamson,1999). Despite the recent theoretical progress in identifying the necessary conditions forPPPs efficiency, non-specialist analysts continue to focus on their ideological dimensions andinterpretations.The rest of this note shows that the biases introduced by ideologicaldiscussions of PPPs are in sharp contrast with the more balanced theoretical and empiricalresearch on the topic.1

What are we really talking about?The notion of PPP is multifaceted and covers a wide diversity of contractual agreementscharacterized by different risk sharing and financing schemes, as well as differentorganizational forms. A broad definition of PPPs is that they are long-term contractualagreements between a private operator / company (or a consortium) and a public entity (bothat the central or local level) under which a service is provided, generally with relatedinvestments.More precisely, PPPs can be defined as global contracts (bundling bothinvestments and service provision) with delayed payments. For instance, in the case ofconcession contracts, these payments are financed through user fees and/or subsidies. In thecase of PFI contracts, they are financed through public payments, which serve asreimbursements1.The world enjoys quite a long experience with these contracts. Concession contracts orequivalents have existed for several hundred years now. PFI contracts are relatively new.They were started in the early 1990s in the UK and have enjoyed regular improvements, oftento upgrade their efficiency payoffs. Figure 1 gives a sense of their importance in Europewhere the leader in their use continues to be the UK. They have financed, annually, 12 to 30billion euros of European public investments annually, reaching a peak just before thebeginning of the recent crisis.Source: EPEC Market Update 20131Hybrids may exist with payments depending on both user fees and public payments.2

PPPs’ Promises and ThreatsThe lower degree of political interference (Boycko et al., 1996), risk transfers and the moreup-to-date technical and management knowledge of private actors dealing with a globalcontract bundling investments and service provision (Hart, 2003) are widely viewed as thethree main drivers of improvements in efficiency that PPP can contribute to the delivery ofpublic services.But research also shows that the reality is a lot more subtle and theefficiency outcome of PPPs should be expected to be less predictable than often assumed.The unpredictability mainly stems from the incomplete nature of PPP contracts resulting fromthe fact that they do not specify what the contracting parties should do in every futuresituation. This generates transaction costs – i.e. difficulties in implementing and enforcingthese contracts (Williamson, 1985) and hence threats to PPPs.The theoretical research justifies the cases made to push public authorities to improve theirability: (i) identify projects to be financed through PPPs (i.e. projects creating social value);(ii) specify the characteristics of the service they commission; (iii) deal properly with theaward stage; (iv) work through the contractual details, and (v) invest in the enforcement ofthe contract, (See the other papers of this journal issue for more details about what the theorysuggests at every steps of PPPs implementation). Any government mistake on any of thesedimensions is a threat to the efficiency promises of a PPP. How important these threats are isultimately an empirical matter and this evidence is also complex as discussed next.Empirical Evidence: What do we know?Empirical evidence confirm that PPPs can indeed lead to improvements in efficiency butnot necessarily so. The econometric evaluation of various types of PPP experiences showsindeed that the careful choice of control variables, the proper framing of the PPPsinstitutional and sectoral context and the careful avoidance of selection biases in samplechoices matter to the conclusions reached by empirical tests of the impact of PPPs onefficiency.Recognizing the relevance of these factors allows the identification of thecircumstances under which PPPs are likely to enhance efficiency and those under which theywill not. This section briefly reviews the empirical lessons on the circumstances that maylimit the efficiency payoffs of PPPs for a wide range of infrastructure public services.3

The risks of optimism biases in projects selectionFailures to improve efficiency with a PPP start with the extent to which a project meets aneed. Ideally, a careful demand study needs to reveal the willingness to pay for the projectand when externalities are relevant, the state has to make sure that they can be dealt with notonly equitably for users and taxpayers but also efficiently from a technological viewpoint.This identification is not as simple as it sounds and strategic overestimations of demand arecommon practice (Trujillo et al. 2002, Flyvbjerg 2014). This manipulation can be done atthe initiative of the public or the private sector. It turns out that who identifies the need andinitiates the case for a project is not an important driver of the large number of cases ofoptimism bias observed around the world. White elephants can benefit both politicians andprivate providers. They do not seem to be reduced by PPPs.Consider the case of Spain. The recent experience of PPPs in Spanish transports revealshow a systematic large-scale ex-ante overestimation of demand can lead to an oversized ormisallocated transport network (e.g. Bel et al. (2014)). The optimism bias in transport ridingon a country growth strategy anchored in the construction industry has been costly. Spain hasended up closing a large number of recently built regional airports and train stations due to alack of demand.Many of its toll roads, also built under PPPs, are just as financiallyunsustainable.A basic sense of the relevance of cost functions had allowed a fair number of economiststo raise concerns with the quality of project sizing for a much larger number of countries andmany of these papers pointed to the cost inefficiency in ports (Gonzàlez & al 2009), airports(Oum et al 2008) or roads (Bel et al 2014). This is not to say that all PPPs have failed. Manyhave indeed been quite effective. But it serves to show that project selections biases happen,probably too often, and that the suppliers of PPPs may not have an incentive to raise red flagsearly on. This problem is even more central in PFI like contracts for which private firms’revenues are not conditioned to future demand. If value for money reports are generallymandatory, they are susceptible to manipulations (House of Commons, 2011).As suggested by Bel et al (2014) in the Spanish case, the mis-targeting of demand can beconsistent with either incompetence or collusion between public and private actors. Eitherway, efficiency is not the outcome of the initial need identification phase, whether a privatepartner is present or not.4

The failures of the procurement processThe second driver of the efficiency of PPPs for which empirical evidence is quite robustis the quality of the procurement process. In countries in which public procurement is poorlyorganized or corrupt, PPPs offer an opportunity to reform procurement processes to cut costsby increasing competition for a project or a market. It serves to go around the inertia ofprocurement practices inherited from times in which governments were trusted to deliverpublic services in the interest of consumers.Although significant improvements have been achieved in recent years, the challengeremains, in both developed and developing countries. A recent survey conducted by PwCand Esorys (2013) on behalf of the EU shows that corrupt procurement processes continue tobe a significant issue, in particular in infrastructure. In a sample of 8 EU countries, thesurvey finds that the highest probabilities of corruption are the staff development services(23–28%) and the construction of wastewater plants (22–27%). The probability of corruptionis lower for rail (15–19%), for road (11–14%), and airport runway construction works (urban& utility construction): (11–13%).The overall direct costs of corruption in publicprocurement in 2010 ranged between EUR 1.5 billion and EUR 2.3 billion, about 19% of theestimated value of tenders for public expenditures on works, goods and services published inthe EU electronic tendering system in the 8 EU Member States covered by the survey.Although corruption is a serious problem, it should not hide that the design ofprocurement itself is often a serious limitation of the extent to which governments can makethe most of the opportunities offered by PPPs. For a large sample of developing countriesbenefiting from World Bank and Japanese aids, Estache and Iimi (2011) show how publicsector procurement rules often tend to limit or distort competition in public markets to deliverinfrastructure needs, such as roads or water and sanitation facilities.The inefficiencyassociated with the limitations of the process represents at least 8% of the infrastructure needsof the developing world—and much more so countries in which corruption and incompetencecombine to allow inflated costs.The upshot is that PPPs help, but they are not a sufficient condition to ensureimprovements in efficiency as compared to pure public provision. The recent EuropeanConcession Directive voted in February 2014 highlights that these problems are also presentin PPPs to a large extent (Directive 2014/23/UE). Indeed, the Commission justified the needfor a new European Directive because many Concession contracts where directly awarded,without any prior notification nor call for tenders (Saussier 2012).5

Theory suggests that designing procurement procedures when the risks of corruption orcollusion are serious demands a willingness to adopt somewhat counter-intuitive processes tooptimize efficiency prospects, including granting some discretionary power to publicauthorities. For instance, Bajari et al. 2009, using a data set of contracts awarded in thebuilding construction industry in Northern California from 1995-2001 by private authorities,found that more complex projects – for which ex ante design is hard to complete and ex postadaptations are expected – are more likely to be negotiated, while simpler projects areawarded through competitive bidding. Furthermore, buyers rely on past performance andreputation (Spagnolo 2012) to select a contractor when they decide to award the contractthrough direct negotiations. This suggests leaving open the possibility to negotiate to acertain extent especially for PPPs that are complex and may not rely automatically onweighted criteria to define the best economic offer.The extent to which a PPP “skims the cream” of a sectorThe third driver of the impact of PPP on efficiency identified in the empirical literaturerequires some refocusing of the discussion. Most of empirical literature tends to look at theextent to which PPPs can influence the efficiency in the context of a specific project. From asector perspective, however, this does not necessarily guarantee efficiency.If creamskimming takes place, economies of scale or scope can result in a higher aggregate costs forthe sector, i.e. the aggregate performance of a highly effective PPP and of a poorly efficientresidual sector can lead to a lower aggregate efficiency level (Estache and Wren-Lewis2009). This concern helps explains the differences in the degree of unbundling in sectorsobserved from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s and ever since.When Cameroun decided to concession its electricity company, it opted not to unbundlethe vertically integrated public company. Part of the argument was that it reduced theperception of risks by the investors. But it was also because there was a risk that the fiscalcosts of the non-competitive segments of the client basis would be excessive since servingthem would have to rely on higher cost techniques. Similar observations can be madeconcerning the packaging of water concessions in Argentina for instance or in discussions onthe regionalization of ports and railways services in both developed and developing countries.The challenges of matching the contractual choice with the institutional contextThe fourth efficiency driver is the institutional context in which the PPP takes place. Thisinstitutional context has several dimensions, including the approach adopted to supervise6

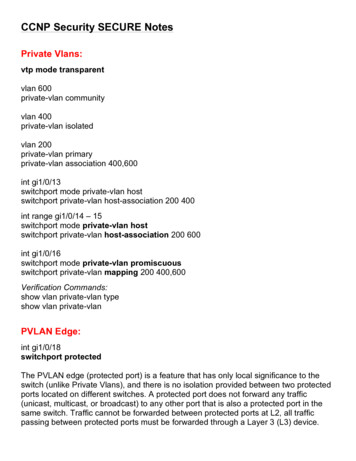

and/or regulate the sector and the specific nature of the PPP contract (i.e. concession,constructions, maintenance, management ). PPPs tend to embed the basic regulatoryframework that will guide their evolution as it relates to basic features such as prices, quality,penalties, termination and the like. Very often, the regulatory framework is embedded withinthe formal contract and there is no regulator. However, empirical evidence suggests that thecontract is not always a good tool to regulate PPPs, especially when the project is complexand the contract very incomplete.Because PPPs are long-term contracts, they need to adapt through times. This give riseto frequent renegotiations (See Table 1). Those renegotiations can be viewed as evidence ofopportunistic behaviors from contracting parties. As stated by Guasch & al 2008 “High ratesof contract renegotiation have raised serious questions about the viability of the concessionmodel in developing countries” (p.421). Others suggest that such renegotiations are“renegotiations without any hold-up” highlighting corruption and political issues at stake insome countries concerned by PPPs (Engel & al 2006). However, because renegotiations aresometimes useful, in a sense, it is possible to say that the frequency of contract renegotiationmay provide concessions 'relational' quality (Spiller 2009; Beuve & al 2013). Whatever thereason why PPPs are renegotiated, one central message is that renegotiations are the rule, notthe exception and this has an impact on efficiency. The institutional framework in whichPPPs are evolving are not neutral to explain their efficiency.Table 1. Some studies on the frequency of renegotiations in PPPsGeographical AreaSectorLatin and CaribbeanAll sectors% of ty41%Transport78%United 007)United KingdomCar ParksAll sectors73%55%Beuve & al (2013)NAO (2001)(Guasch, 2004)(Engel et al., 2011)andSaussier,.7

The econometric evidence demonstrating that effective regulators can allow PPPs toimprove total factor productivity and labour productivity abounds, even if it varies acrosssectors and across regions. Although it has been quite positive for the telecoms sector andoften positive for transport (largely because competition works well in these two sectors) thestory is a lot more complex for electricity and water and sanitation (Erdogdu, 2011, 2013).For electricity, public-private investments in generation and large-scale investments such asdistribution and transmission concessions has generally, lead to significant improvements inefficiency. In water and sanitation, the evidence of an increased efficiency due to privatesector participation. (e.g. von Hirshhausen et al 2011 for a recent survey) is less clear even ifempirical evidence in France show that prices are not higher with PPPs compared to directpublic management for French big cities without any national regulator (Chong & al 2014).The evidence is not that clear either for airports (Oum et al (2011)) or ports (Gonzalez andTrujillo (2009), Vasigh and Howard, (2012)).SustainabilityThe final dimension deals with the sustainability of any efficiency gain achieved by aPPP. Economists but also political scientists have been very effective in recent years inincreasing our collective awareness of the various dimensions of governance, from weakinstitutions surrounding PPP to the overwhelming politics of PPP. Berg et al (2012) point outin their study of telecoms that it affects more private firms than government-owned firms.For transports, Galilea and Medda (2010) suggest that corruption is not just aboutprocurement. Governance and democratic accountability also matter to the impact of a PPPon the sustainability of the sectoral efficiency gains they may have delivered. Galilea andMedda (2010) find a positive association between a low accountability level and a PPP’ssuccess for all transport sectors except toll roads. Less accountable governments “seem morewilling to fulfil the long-term requirements” or are maybe easier to make accountable whenthe PPP process increases the transparency of transactions in the sector.ConclusionOne of the more general conclusion to be derived from this short theoretical and empiricaloverview of research on PPPs’ efficiency is that they deal with specific hazards that are notpresent for private contracts and that understanding the drivers of these hazards is essential tounderstanding the extent to which PPP will help or hurt efficiency. Spiller (2009) wiselyargued that: “the perceived inefficiency of public or governmental contracting is simply the8

result of contractual adaptation to different inherent hazards, and as such is not directlyremediable”. Those different hazards linked to institutional context are now well-identifiedand increasingly well documents. They are, however, still waiting for a general theory(Estache and Wren-Lewis, 2009) to guide and structure empirical research.This isparticularly important as politicians continue to make efficiency commitments on behalf ofPPPs that do not really determining the ways to improve PPPs efficiency. In this context, theevidence also shows regulators and competition agencies have a stronger role to play thatthey are credited for by policymakers betting on PPPs. And so do regulation, liability rules,and authorized contractual provisions, even if their optimal design is likely to differ from onecountry to another because institutional constraints and history are different.More theoretical developments and empirical investigations should obviously be developedto understand how economic actors tentatively deal with the various hazards identified withPPPs, and whether this could be enhanced by innovation in contractual and/or institutionaldesign. This should be a top research agenda, especially because problems that plague PPPsare increasingly recognized and are also present in traditional procurement contracts in abusiness that represents on average 13% of the OECD GDP (OECD 2013). Getting PPPswrong is unlikely to be cheap.ReferencesAthias, L., Saussier, S., 2007 “Un partenariat public-privé rigide ou flexible!? Théorie etapplications aux concessions routières”, Revue Economique, 58, 565–576.Bajari, P., McMillan, R. & Tadelis, S., 2009. Auctions Versus Negotiations in Procurement:An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 25(2), 372–399.Bel, G., A. Estache & R. Fourcart, 2014. “Transport infrastructure failures in Spain:mismanagement and incompetence, or political capture?”, in T. Søreide & A.Williams, eds. Corruption, grabbing and development.Bel, G. & Fageda, X. 2013 "Market power, competition and post-privatization regulation:Evidence from changes in regulation of European airports", Journal of EconomicPolicy Reform, 16 (2), 123-141.Beuve J., de Brux J. & Saussier S. 2014, Renegotiations, Discretion and Contract Renewals:An Empirical Analysis of Public-Private Agreements, Working Paper EPPP,Sorbonne Business School.Boycko, M., Shleifer, A., Vishny, R.W., 1996.Journal, 106, 309–319.“A theory of privatization”, Economic9

Burger, P. and I. Hawkesworth 2011, “How To Attain Value for Money: Comparing PPPand traditional Infrastructure Public Procurement”, OECD Journal on Budgeting, 11(1), 91-146Chong E., Saussier S. and Silverman B. 2014, Water under the Bridge: Determinants ofFranchise Renewal in Water Provision, Working Paper EPPP, Sorbonne BusinessSchool.De Bettignies, J., & Ross, T. 2009, « Public–private partnerships and the privatization of thefinance function: An incomplete contracts approach », International Journal ofIndustrial Organization, 27, 358–368.Engel, E., R. Fisher and A. Galetovic (2006), "Renegotiation Without Holdup: AnticipatingSpending in Infrastructure Concessions," Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper 1567.Engel, E., Fischer, R., Galetovic, A., 2011, Public-Private Partnerships to Revamp U.S.Infrastructure. Hamilton Project report, 1–26.Erdogdu, E. 2011 “What happened to efficiency in electricity industries after reforms?”Energy Policy, 39-10, 6551-6560.Erdogdu, Erkan, 2013. "A cross-country analysis of electricity market reforms: Potentialcontribution of New Institutional Economics,"Energy Economics, Elsevier, vol.39(C), pages 239-251.Estache, A. and A. Iimi 2011, “The Economics of Infrastructure Procurement: Theory andEvidence”, CEPR, LondonEstache, A., Wren-Lewis, L., 2009, “Toward a Theory of Regulation for DevelopingCountries: Following Jean-Jacques Laffont’s Lead”, Journal of Economic Literature,47, 729–770.Flyvbjerg, B. 2014, “What You Should Know about Megaprojects and Why: An Overview”,Project Management Journal, 45 (2), 6-19.Galilea, P. and F. Medda 2010 “Does the political and economic context influence thesuccess of a transport project? An analysis of transport public-private partnerships”,Research in Transportation Economics, 30, 102-109.Gasmi, F., A. Maingard, P. Noumba and L. Virto 2011 “Impact of privatization intelecommunications- A worldwide comparative analysis”, in (2009) Innovation andInformation and Communication Technology in Africa, African Economic Outlook.González, M. M. and L. Trujillo. 2009. « Efficiency measurement in the port industry : asurvey of the empirical evidence », Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 43(2), 157-192.Guasch, J.-L., 2004. Granting and Renegotiating Infrastructure Concession: Doing It Right.The World Bank, Washington DC, USA.Guasch, J.-L., Laffont, J.-J., and Straub, S. (2008). Renegotiation of conces- sion contractsin latin america. evidence from the water and transport sector. International Journalof Industrial Organization, 26:421–442.House of Commons, 2011. Private Finance Initiative. UK House of Commons.Megginson, W. L. and J.M. Netter 2001, "From State to Market: A Survey of EmpiricalStudies on Privatization,” Journal of Economic Literature 39, 321-38910

Oum, T., J. Yan and C. Yu 2008 “Ownership forms matter for airport efficiency: Astochastic frontier investigation of worldwide airports”, Journal of Urban Economics,64, 422-435.Oum, T., N. Adler and C. Yu 2006 “Privatization, corporatization, ownership forms andtheir effects on the performance of the world’s major airports”, Journal of AirTransport Management, 12, 109-121.PwC and Ecorys 2013, Identifying and Reducing Corruption in Public Procurement in theEU, prepared for the European CommissionSaussier S. 2012, “An Economic Analysis of the Closure of Markets and other Dysfunctionsin the Awarding of Concession Contracts », Report for the European Parliament,IP/A/IMCO/NT/2012-11.Spagnolo, G., 2012. Reputation, Competition, and Entry in Procurement, Einaudi r, P.T., 2009. An institutional theory of public contracts: Regulatory implications, in:Ménard, C., Ghertman, M.(Eds.), Regulation, Deregulation, Reregulation:Institutional Perspectives. Edward Elgar.Trujillo, L., E. Quinet and A. Estache 2002, « Dealing with demand forecasting games intransport privatization » , Transport Policy, 9 (4), 325-334Vasigh, B. and C. Howard 2012 “Evaluating airport and seaport privatization: a synthesis ofthe effects of the forms of ownership on performance”, Journal of TransportLiterature, 6-1, 8-36.Williamson, O.E., 1985. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. The Free Press, NewYork, NY, USA.Williamson, O.E., 1999, "Public and private bureaucracies: A Transaction Cost Economicsperspective", Journal of Law Economics and Organization 15, 306–342.11

EPPP DP No. 2014-06 Public Private Partnerships and Efficiency: A Short Assessment Antonio Estache et Stéphane Saussier S Juillet 2014 Chaire Economie des Partenariats Public-Privé Institut d'Administration des Entreprises . 1 Public Private Partnerships and Efficiency: