Transcription

THE CONSTRUCTION OF SICKLE CELLDISORDER IN SAUDI ARABIA: THEINVISIBLE DISEASEAreej Ali AbunarBSN, RN, MNThis thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree ofDoctor of PhilosophySchool of NursingFaculty of HealthQueensland University of TechnologyBrisbane, Australia2017

KeywordsConstructionism, Constructivist Grounded Theory Methods, Culture, Family,Healthcare Worker, Identity, Pragmatism, Saudi Arabia, Sickle Cell Disorder, SocialConstructionism, Symbolic InteractionismThe construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible diseasei

AbstractSickle cell disorder (SCD) is a significant health problem that may lead todisability and/or death. In Saudi Arabia, where the incidence of SCD is relativelyhigh, there is a lack of research on how this disease is experienced. This researchexplored the construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia.The theoretical framework of the research was underpinned by tenets tionism,andsocialconstructionism. The methods of data generation and analysis were guided by theconstructivist grounded theory approach of Charmaz (2014). The research wascarried out within two major hospitals in Jeddah city. The research used purposivesampling to select participants who had a wide range of experiences as healthcareworkers in working with patients with SCD (N 15) and as parents or caregivers ofchildren with SCD (N 25). Forty in-depth interviews with these participants wereanalysed through the processes of open, focused, and theoretical coding.Shaping a reality around sickle cell disorder, the key analytical conceptgenerated in the research, represents the social processes that underpinned theconstruction of meaning of the participants. Three constituent categories generatedfrom the analysis were the invisible disease, positioning of social actors and shiftingperspectives. The dimensions of the experience of sickle cell were contextual andmultilayered. The interrelationship of interactions and the social and culturalenvironment gave focus to the salient issue of the social invisibility of SCD and howthis positioned patients, carers, and health professionals. Thus, the research generatediiThe construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible disease

in-depth insight into how patients, families, and healthcare professionals worked tomake sense of and negotiate the social and cultural dimensions of this disease.These findings will contribute to the ongoing development of strategies toimprove knowledge and practices regarding SCD in Saudi Arabia; the improvementof services provided to children with sickle cell disorders and their families in SaudiArabia; the improvement of education strategies for families genetically predisposedto having children with SCD; and the further development of strategies to reduce theprevalence of SCD. These measures, if conceived within a broad framework thataddresses the deep cultural and social attitudes and practices around health andillness in Saudi Arabia, may engender more effective education and healthcareprocesses that optimise the experiences of those with SCD and maximiseopportunities for education of the population as a whole in relation to this disease.The construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible diseaseiii

Table of ContentsKeywords . iAbstract .iiTable of Contents . ivList of Figures .viiList of Tables . viiiList of Abbreviations . ixStatement of Original Authorship . xAcknowledgements . xiCHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION . 11.1Introduction. 11.2The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia . 21.3Research Background . 61.4Research Problem . 81.5Research Question . 91.6Research Aims . 91.7Significance of the Research . 101.8Reflexivity and the Role of the Researcher . 131.9Thesis Outline . 16CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW . 182.1Introduction. 182.2History and Incidence of Sickle Cell Disorder . 182.3Prevalence of sickle Cell Disorder in Saudi Arabia . 222.4Premarital Screening Programs. 262.5Sickle cell disorder and Health Problems . 292.5.1 Anaemia. 292.5.2 Pain . 302.5.3 The Management of SCD . 302.6Chronic Illness and Identity . 352.7Chronic Illness and Family . 392.8Summary . 42CHAPTER 3: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK . 443.1Introduction. 443.2Social Theory and Social Action . 443.3Pragmatism . 473.4Symbolic Interactionism . 493.5Self Theory . 533.6Looking-Glass Self Theory . 54ivThe construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible disease

3.7Role Theory . 553.8Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory . 563.9Social Constructionism . 583.10Summary . 62CHAPTER 4: RESEARCH DESIGN . 634.1Introduction . 634.2Research Methodology . 634.3Research Setting. 664.4Recruitment . 664.5Research Sample . 674.5.1 Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Participants. 694.6Research Methods . 704.6.1 Data Generation . 704.6.2 Data Analysis . 724.7Rigour, Credibility and Trustworthiness . 784.8Ethics, Health and Safety . 794.9Summary . 82CHAPTER 5: THE INVISIBLE DISEASE . 835.1Introduction . 835.2Coming to Know the Disease . 865.3Uncertainty. 1065.4Lives Disrupted . 1135.5Summary . 123CHAPTER 6: POSITIONING OF SOCIAL ACTORS . 1266.1Introduction . 1266.2Constructing Care . 1286.3Us and Them . 1406.4Summary . 157CHAPTER 7: SHIFTING PERSPECTIVES . 1617.1Introduction . 1617.2Reconfiguring Normality . 1647.3Negotiating Reality . 1707.4Re-defining the Future . 1797.5Summary . 183CHAPTER 8: DISCUSSION . 1878.1Introduction . 1878.2Shaping a Reality Around Sickle Cell Disorder . 1908.2.1 Normalising . 1968.2.2 A reality . 1988.2.3 A social disease . 2008.3Medicalisation . 2028.4Identity . 203The construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible diseasev

8.5Strengths and Limitations of the Research . 2068.6Implications and Recommendations . 2088.6.1 Implications and recommendations for policy . 2088.6.2 Implications and recommendations for clinical practice . 2108.6.3 Implications and recommendations for future research . 2118.7Personal Reflection . 2118.8Conclusion . 212REFERENCES . 214APPENDICES . 239Appendix A Ethical Approval Letters . 239Appendix B Participant Information Sheet and Consent Form . 243Appendix C Interview Questions . 258Appendix D Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants . 263viThe construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible disease

List of FiguresFigure 1.1: Map of Saudi Arabia .2Figure 5.1: The analytical concept and categories of The Invisible Disease . 86Figure 6.1: The analytical concept and categories of Positioning Social Actors. 128Figure 7.1: The analytical concept and categories of Shifting Perspectives . 163Figure 8.1: The key analytical concept Shaping a Reality Around Sickle Cell Disorder and itsconstituent elements . 189The construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible diseasevii

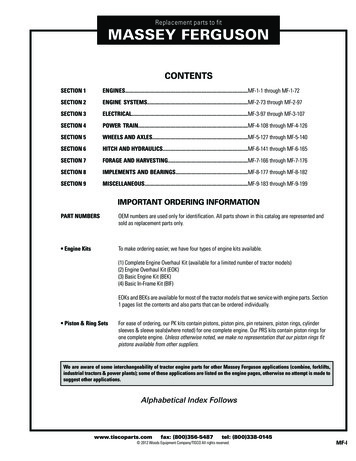

List of TablesTable 2.1: The estimated prevalence of sickle cell disorder. 21Table 2.2: Prevalence of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia . 23Table 4.1: Example of initial coding. . 73Table 4.2: Example of focused coding. . 74Table 4.3: Example of memo writing. 75Table 4.4: The key analytical concept and its constituent elements . 78viiiThe construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible disease

List of AbbreviationsWorld Health Organisation (WHO)United Nations (UN)Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)Sickle cell disorder (SCD)Sickle cell trait (SCT)The construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible diseaseix

QUT Verified Signature

AcknowledgementsI would like to thank King Abdulaziz University for offering me thescholarship to gain my postgraduate degrees. Thank you to Queensland University ofTechnology for giving me the opportunity to undertake my PhD research.I would like to express my thanks to my supervisors: principal supervisorAssociate Professor Carol Windsor, for her ongoing support, patience, andencouragement, for providing me with advanced, critical knowledge and guidancealong the way, and for sharing this unique experience with me; associate supervisorDr Joanne Ramsbotham, for her support and encouragement; and external supervisorDr Fatin Al Sayes, for her support, encouragement, time, and facilitating the researchprocess and the communication within the hospital.My thanks also to the language and learning educators, Dr Martin Reese andMrs. Rena Frohman for supporting and improving my writing skills. I would alsolike to thank professional editor, Kylie Morris, who provided copyediting andproofreading services, according to university-endorsed guidelines and the AustralianStandards for editing research theses.Thank you to both hospitals for approving and providing access for thisresearch. I would also like to thank all of my research participants for sharing theirexperiences and time.I also wish to express my appreciation and special thanks to my father Ali andmy mother Fawzia, for their love, prayers, encouragement, listening, relieving mypressure, and unique support and trust throughout my life. I would like to express mydeepest thanks to my sisters, Alaa, Esraa, and Elaf, and my brother Anas for theirThe construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible diseasexi

love and support. My sincere thanks to my husband Marwan Tamr and my daughters,Lama, Sama, and Jana for their ongoing love, fun, support, motivation, cooperation,and patience. Thank you to my relatives for their encouragement and support.Thanks also to my friends for supporting, sharing, and listening to my experience.xiiThe construction of sickle cell disorder in Saudi Arabia: The invisible disease

Chapter 1: Introduction1.1INTRODUCTIONThe objective of this research was to explore the construction of sickle celldisorder (SCD) in Saudi Arabia. Sickle cell has been largely “neglected” (Ware, 2013) in contrast to other more high profile conditions, such as HIV/AIDS. Sicklecell has also not been overtly recognised as a disorder internationally for a variety ofreasons. The most potent reason is that SCD has historically been positioned within,what Dyson and Atkin (2011) refer to as, discourses around socio-economic status,ethnicity, and racism. A related issue is that this condition is prevalent in developingcountries where relatively little health research is conducted (Marsh, Kamuya, &Molyneux, 2011). Indeed, Ware (2013) argues that “only with improved recognition and a concerted world-wide effort can we begin to address this disparity [between thetreatment of communicable and non-communicable diseases] and offer life-savinginterventions to millions of affected children” (p.1). This led the United Nations(UN) to declare, in 2008, that June 19th would henceforth be “World Sickle Cell Day” in order to increase awareness about this disease (United Nation, 2008).Sickle cell disorder is less recognised in Saudi Arabia than many other nationseven though it has one of the highest incidences in the world. According to AlSuwaid, Darwish, and Sabra (2015), the sickle cell gene was recognised for the firsttime in 1963, by Lehman, Maranjian, and Mourant, in the eastern region of SaudiArabia. As Lehmann et al. (1963) later wrote; “The distribution of sickling in Saudi Arabia is of particular interest because of its relation to malarial distribution and theorigin and movements of the population concerned” (p.492). The experience ofsickle cell is also complex because it is mediated through historical, cultural, Chapter 1: Introduction1

religious, and social practices. Thus, a range of complex and interrelated factorsunderpin this health issue in the Saudi Arabian context. This points to the need tounderstand the significance of SCD in Saudi Arabia and to situate sickle cell within abroader context, one that extends beyond the biological disease to encounter thesocial world of SCD.This first chapter provides contextual information about the Kingdom of SaudiArabia; presents the research background by exploring the prevalence and incidenceof haemoglobin disorders including sickle cell disease; and demonstrates thesignificance of this disease within Saudi Arabia. The chapter then moves on to theresearch problem, the research question and aims, the significance of the research,role of the researcher, and finally the thesis outline.1.2THE KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIAFigure 1.1: Map of Saudi ArabiaSource: Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, Washington, 20152 Chapter 1: Introduction

Saudi Arabia is a Middle Eastern country located in the southwest corner ofAsia and stands at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa (Kingdom of SaudiArabia Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015). The kingdom occupies almost 80% of theArabian Peninsula and covers over 2,150,000 square kilometres (Kingdom of SaudiArabia Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015). It is surrounded by the Red Sea to thewest, by Jordan, Iraq, and Kuwait to the North, by the Arabian Gulf, Bahrain, Qatar,and the United Arab Emirates to the East, and by Oman and Yemen to the South(Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, Washington, 2015).Saudi Arabia is divided into 13 provinces; Riyadh, Makkah, Madinah,Northern Borders, Tabuk, Al-Jouf, Hail, Al-Baha, Asir, Najran, Jizan, Qassim, andthe Eastern province (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015).The major cities in Saudi Arabia include the capital, Riyadh, the two holy citiesMakkah and Madinah and finally Jeddah, the second largest city after Riyadh and thecommercial centre (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015).The estimated population in Saudi Arabia approaches approximately 30 million ofwhich a third are non-Saudi nationals (Central Intelligence Agency, 2016). Ethnicgroups in Saudi Arabia comprise 90% Arab and 10% Afro-Asian (CIA, 2016). Thegeography and distribution of the population is important because the prevalence ofSCD is not uniform throughout the country. Neighbouring nations and the ethnicgroups that live in the eastern and the southern regions of Saudi Arabia are reportedto have higher rates of haemoglobin disorders than the Saudi capital and other twomajor cities.Saudi Arabia is a monarchy, declared as such in 1932 by King Abdulaziz AlSaud, and based on Islam (Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, Washington, 2015). Thegovernment is headed by the king (at present King Salman Al-Saud). The political Chapter 1: Introduction3

system in Saudi Arabia abides by Arabic and Islamic laws as a basic legislativebranch (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015). As such, theconstitution in Saudi Arabia is governed according to Islamic Law (CIA, 2016)which is grounded in the Holy Qur’an and the Sunnah (Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, Washington, 2015) and which forms the basis of the legal system (CIA,2016). The legislative branch is the Consultative Council or Majlis al-Shora (CIA,2016). The official language in Saudi Arabia is Arabic (CIA, 2016), although Englishis commonly spoken in urban areas (Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, Washington,2015). Almost 95% of the population is educated, a figure that reflects individualsaged 15 years and over who can read and write (CIA, 2016).From the above, it is clear that Saudi culture has been shaped by religion as thedominant influence, followed by education, economic status, and race (Aldossary,While, & Barriball, 2008; Al-Shahri, 2002). Culture is a complex concept and for thepurpose of this research and congruent with the methodology is defined on the onehand, as the self-making of humans through their actions and on the other hand, asthe making of the world through social processes. Thus, in understanding the socialcontext of the research, social interaction is considered inseparable from structure(Grossberg, 2013).Saudi traditions originate from Islamic teachings and Arab customs that havebeen passed down through families and reinforced in schools from childhood (RoyalEmbassy of Saudi Arabia, Washington, 2015). Nonetheless, the geographicaldiversity of Saudi’s regions and of its neighbouring countries and tribal factors havealso shaped the social and cultural traditions in Saudi Arabia. As stated by AlRasheed (2010), the distribution of the Saudi population is based on tribal differencesand regions that have given rise to different subcultural groups in Saudi Arabia.4 Chapter 1: Introduction

Furthermore, in Saudi Arabia, there are different social, cultural, and demographicfeatures that vary significantly between different regions and also within regions(Elsayid, Al-Shehri, Alkulaibi, Alanazi, & Qureshi, 2015).The authority of Islam can be observed in the behaviours and practices ofSaudi individuals in all aspects of life (El-Gilany & Al-Wehady, 2001; Littlewood &Yousuf, 2000). As noted by Aldossary et al. (2008): “Islamic practice is connected to spirit, behaviour, food, language and social traditions” (p. 126). The framework ofIslamic religious beliefs has shaped the social and the economic development of theSaudi population (Aldossary et al., 2008; Littlewood & Yousuf, 2000).Economic growth has been rapid and relatively recent. Saudi Arabia has an oilbased economy and the major economic activities are controlled by the government.Indeed, it is the world’s largest producer and exporter of oil (CIA, 2013; Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, Washington, 2015). Natural resources include petroleum,natural gas, gold, copper, and iron ore and the economy is driven by the export ofpetroleum and petroleum products and the import of machinery and equipment,chemicals, foodstuffs, textiles, and motor vehicles (CIA, 2013). There is also someagricultural production around dates, wheat, tomatoes, barley, citrus, melons, milk,mutton, chickens, and eggs (CIA, 2013). Being perceived as a wealthy nation hasinfluenced the Saudi population’s perceptions of health, chronic illness, andresponsibility for healthcare. Because Saudi Arabia is a rich country, families may beencouraged to have more children and for varied reasons. At the time of thisresearch, for every sick child, families received increased financial support from thegovernment. Support was provided by cooperative societies, charities, andcomprehensive rehabilitation centres for the disabled under the Ministry of SocialAffairs. Sickle cell patients were also primarily treated in government hospitals due Chapter 1: Introduction5

to the low socio-economic status of the majority of affected families. The level ofgovernment assistance was because many individuals with sickle cell disorder areunable to continue with education and secure employment.The social context of Saudi Arabia is unique in the world where the influencesof place and history are strongly evident in different elements of the population. Assuch, there are a variety of socio-cultural influences that shape the way differentdemographic groups make decisions and take action around haemoglobin disordersin Saudi Arabia. As an example, people from the Southern regions strongly supportconsanguineous marriage1 due to tribal affiliation and thus the incidence of geneticdiseases such as sickle cell is high in this geographic area. A detailed exploration ofthis issue is provided in the following sections.1.3RESEARCH BACKGROUNDWorldwide, haemoglobin disorders, includin

BSN, RN, MN This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Nursing Faculty of Health Queensland University of Technology . time in 1963, by Lehman, Maranjian, and Mourant, in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia. As Lehmann et al. (1963) later wrote; "Thedistributionof .