Transcription

PROCTOR RESEARCH BRIEF DECEMBER 2021The Forte Way: A Coaching CaseStudy during the COVID-19PandemicBy Tanishia Lavette Williams, Tracey Freiberg, and Sabrina AbbamonteEXECUTIVE SUMMARYLocated in one of the most culturally diverse and resource-deprived neighborhoods in the Queens borough of New YorkCity, Forte Preparatory Academy produces middle school graduates who have consistently outperformed their peers.The school, serving a population where 90 percent of the students receive free or reduced lunch and both the specialeducation and English language learner populations exceed City averages, boasts a world-class education that preparesstudents to matriculate into the best high schools in the city. In May 2021, the teaching staff at Forte participated in theTeacher Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001), which captured the teachers’ perceptions ofefficacy in three different areas, or factors: Student Engagement, Instructional Strategies, and Classroom Management.The Forte data exist as a fraction of a larger data set that is being used to inform the relationship, if any, of a teacher’srace, gender, experience, or assigned grade level on the three factors examined in the instrument. In this case study, weexamine one instructional improvement initiative that the staff members attribute to their successes.ABOUT THE AUTHORSTanishia Williams is a Ph.D. Candidate in Public Urban Policy at the Milano School of Policy,Management, and Environment at The New School and Samuel Dewitt Proctor Institute VisitingScholar at Rutgers University. Tanishia was featured in the Peabody award-winning 180 Days: AYear Inside an American High School and has spent the last twenty-two years as an educator in NewYork City, DC, and Newark as a teacher, principal, executive director for student support servicesin special education and instructional superintendent. Her research expertise and interests areinterdisciplinary in nature with a focus on education, Critical Race Theory, race scholarship, andsocial inequality. Tanishia can be reached at willt616@newschool.edu.Tracey Freiberg is a Visiting Professor of Economics at the Peter J. Tobin College of Business atSt. John’s University. She holds a Ph.D. in Public in Urban Policy from the Milano School of Policy,Management, and the Environment at The New School. Professionally, Tracey has over 10 yearsof experience in insurance, financial services, consulting, research, and academia. Her researchexpertise and interests are interdisciplinary in nature with a focus on labor markets, economics,public policies, and community well-being. Tracey can be reached at freit300@newschool.edu.Sabrina Abbamonte is a Bachelor of Science student and apart of the fast-track masters programat St. John’s University. She is currently studying Marketing for her undergraduate degree andMarketing Management for her graduate degree at the Tobin College of Business. Sabrina can bereached at sabrina.abbamonte18@stjohns.edu.SAMUEL DEWITTPROCTOR INSTITUTEfor Leadership, Equity, & Justice

THE FORTE WAY: A COACHING CASE STUDY DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMICTHE ROLE OF EFFICACY IN STUDENTACHIEVEMENTAs described by Donohoo, et al. (2018), teacher efficacyis the single most important predictor of studentachievement, yielding more than three times greaterpredictive ability than socioeconomic status. Forwardingthe literature of teacher efficacy (Dembo & Gibson,1985; Donohoo et al., 2018; Donohoo et al., 2020;Fives & Buehl, 2009; Siwatu, 2011; Siwatu et al., 2017;Stewart, 2012; Wolters & Daugherty, 2007), our researchaims to highlight the actions taken at Forte at the heightof instructional pivots brought on by COVID-19 andremote learning.Within a few weeks of COVID-19 spreading feverishlythroughout the U.S., states quickly pivoted theirinstructional delivery to service students whileconforming to health guidelines. In New York City,schools closed quickly and teachers were given oneweek to redesign instruction to provide lessons remotely.School instruction, culture and rules all changedvirtually overnight. By large, New York City teacherswere left out of the coordination of digital devices tostudents and allowed to focus solely on deliveringquality virtual instruction of the same caliber as theirin-person instruction. The task was not easy. Schoolwas disrupted. Homes were disrupted. Countless liveswere lost. Through all the changes and extraordinarycircumstances, teachers were tasked with servingstudents. Despite the changes in instructional delivery,the teachers of Forte Academy maintained a high levelof self-reported efficacy.Tschannen-Moran and Barr (2004) define collectiveefficacy as the unified staff perception to make positivechange in students’ educational outcomes. Essentially,if and when teachers believe that they can have alasting impact, their collective beliefs and actions resultin increased collaboration, increased positive schoolculture, and shared practices that yield increased studentachievement. An extensive literature of the benefitsof collective cultural efficacy preceded the pandemic(Adams & Forsyth, 2006; Bandura, 1977, 1993, 1997; R.Goddard, 2002; R. D. Goddard et al., 2004; TschannenMoran & Barr, 2004). Long before COVID-19 alteredteaching and learning in school buildings, school leaderssought out ways to build a sense of efficacy as a methodto foster positive school culture and increase studentachievement.To that end, we utilized the Teacher Sense of EfficacyScale (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001) that allowed usto review self-reported efficacy at Forte across threefactors: Student Engagement, Instructional Strategies,and Classroom Management. Using the 24-questionlong form, we were able to segment the Forte case bya variety of comparative variables (race, experience,gender and teacher-assigned grade level). The lessonslearned from Forte Academy show ways that schoolculture and efficacy can be forged despite exceptionalcircumstances. We intend to use these data to not onlyinform future professional development but also get a2

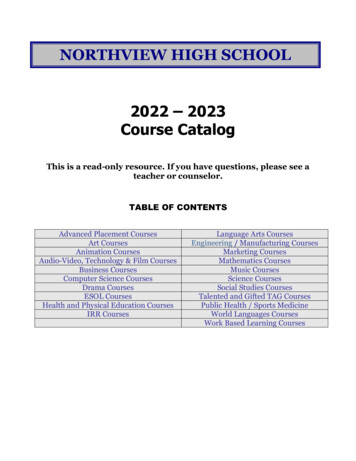

THE FORTE WAY: A COACHING CASE STUDY DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMICTABLE 1: SUMMARY OF RESPONDENTS AND AVERAGESTSES Factor 42100%7.347.057.287.69American Indian or Alaska lack or African 7.64Female2764%7.427.147.417.710-3 years1331%7.297.067.217.614-7 years1740%7.547.107.557.968-11 years921%7.567.027.568.1112 ExperienceGrades taughtbetter understanding of the trends within the variablesat Forte and potentially other NYC schools.EVIDENCE FROM FORTE PREPARATORYACADEMYTable 1 shows select descriptive statistics fromForte Preparatory Academy. We obtained a 100percent response rate from teachers at the school byadministering TSES during a professional developmentsession. We show the preliminary TSES results by usingthe averages accumulated. Each respondent answered all24 questions regarding aspects of job performance withnumeric values ranging from 1 to 9, where 1 indicates“Not at All” and 9 indicates “A Great Deal.” Teachers atForte averaged 7.34 (out of 9) overall, indicating theteachers cumulatively feel “Quite a Bit” effective attheir jobs. The Forte teachers (on average) felt the mosteffective (comparatively) in managing their classrooms,with an average of 7.69 and the least effective engagingstudents, with an average of 7.05. Based on the waythe coaching initiative is structured at Forte, which isdetailed in the next section, it is encouraging that theteachers collectively feel most effective in classroommanagement.We also examined averages across different subpopulations of teachers: race, gender, experience, andthe number of different grades the teachers taught.Here, we use: Race and Gender as demographic variables of interestfor professional development. Experience as a Human Capital variable where moreexperienced teachers are assumed to be moreeffective (Ost, 2014). Grades Taught as an indicator if the teacher is3

THE FORTE WAY: A COACHING CASE STUDY DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMICresponsible for teaching multiple grades, andtherefore more students with more resources arerequired.Notable trends in the subgroups include: The higher averages in Classroom Managementacross all subgroups may speak to the efficacy of thecoaching program at Forte. There may be complicated racial components thatare not sufficiently captured using averages. As aschool with an extremely diverse student population,we need more specific information on not only theteachers but also the students in order to make anysignificant conclusions about race as an indicator ofefficacy. Female teachers had higher averages across theboard than male teachers. In general, more experienced teachers reportedfeeling more effective, versus their less experiencedcounterparts. The overall average increased as moreexperience was added, but that trend did not holdacross the TSES factors. For example, teachers with12 years or more of experience had the highestaverages in Student Engagement, but teachers with8-11 years of experience had the highest averages inInstructional Strategies and Classroom Management.Although this preliminary analysis is a part of a larger, morein-depth synthesis, we used descriptive statistics coupledwith qualitative data obtained via semi-structured focusgroups to provide immediately usable data for the Forteteam. While one reason for administering the surveywas to give the Forte administration an idea of how theirteachers were feeling about their efficacy, especiallywith the complications of the COVID-19 pandemic,it was also an exercise in gathering grade level andcontent-specific needs in each of the three factor areasto drive professional development. More concretely,the leadership team was able to review the anonymousoutcomes of the 24-item survey and review theaverages for each item. For example, the low averages(comparatively) for eighth grade teachers highlightpotential professional development for teachers at thatgrade level.A Coaching Model for SuccessWhile there are several observable actions of teachersand leaders that contribute to a healthy schoolcommunity and positive teacher sense of self-efficacy,Forte’s intensive coaching model surfaced not only asone of the most frequently articulated attributes tosuccess across administrators and teachers, but also asone of the most unique features of Forte’s professionaldevelopment program. As detailed below, each individualteacher is enveloped in support from a coaching teamand leadership guidance. The coaching guidance andleadership structures work harmoniously to provideboth first-year and experienced teachers support ininstructional delivery and classroom management. SeeFigure 1.FIGURE 1The Forte Coaching and Leadership ModelFrequent and Timely FeedbackCoaching begins at the start of the school year in whatis called the “8-week push.” During the first two monthsof the academic year, the coaching team (composedof teacher leaders, leadership team members, anddedicated instructional coaches) spends a significantamount of time in each classroom, reviewing studentdata and determining needs for the year. The baselinesthat are drawn at the onset of the school year drivethe coaching program in subsequent months. Duringthe initial meetings, teachers lead their personalgoal development with their coaches and the schoolcommunity determines school goals.Once targets are set from the baseline data, the coachesprovide consistent feedback on the teacher lesson plansand classroom teaching. Each week, teachers receiveup to three, short, informal observations from theircoaches, who provide immediate written feedback withsuccesses and instructional “pushes” for subsequentlessons. During biweekly, data-driven meetings, teachersand coaches work together to review trends that eithersurfaced in the teachers’ lesson plans or during theclassroom observations. The coaching is grounded inthe targets that were collaboratively set at the start of4

THE FORTE WAY: A COACHING CASE STUDY DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMICthe year. One teacher credits “the attention to detail”prevalent in feedback to their growth as a successfulteacher (Anonymous Teacher 22, 2021).The leadership team at Forte conducts what they referto as the School Review at the midpoint of the schoolyear. During this time, the leadership team “zooms out”to gain insight into the school’s progress toward goalsand the weekly coaching is fine-tuned to target schoolbased needs (Anonymous Leadership 02, 2021).Consistent Professional DevelopmentProfessional development is an integral part of theForte structure. “Other than intentional opportunitiesto recharge, professional development is nevercanceled” (Anonymous Teacher 13, 2021). Professionaldevelopment is categorized as any series of trainingsessions that build pedagogical skill, affirm positiveschool culture or review resources that result inimproved teacher quality and effectiveness. Trainingbegins with teachers during the summer. Forte’scurrent principal explains that summer professionaldevelopment provides teachers with a set of skills thatallow them to easily manage classroom behavior earlyin the school year so they can focus all of the availableinstructional time on teaching and learning. School-wideprofessional development occurs weekly for two hours.High ExpectationsA common theme articulated among the staff is a highlevel of expectation, referred to as the Forte Way. TheForte Way can be described as a resolute dedication toinstructional improvements and steadfast devotion tothe achievement of all students. Teachers who remainat Forte for over three years explain that the Forte Waycomes as easily as walking. Those teachers reflect thatin their first few years they spent a significant amount oftime learning the structures and processes of the school.The Forte Way includes shared language, ritualizedprocesses to manage classroom behaviors, and specificexpectations to provide instruction.Collaborative Community with a Growth MindsetAlong with teacher efficacy, positive mindset hasbeen credited as one of the most influential factors ofstudent success. Forte does not fall short in specificstructures and actions that cultivate positive mindsetand community. From their intentional use of socialmedia that showcases students’ talents to the daily useof Slack to keep practitioners connected and apprisedof immediate students’ needs, the systems that Forteput in place to nurture positive community and growthmindset set them apart and positively contribute to thesuccess of their academic program.TAKING STEPS FORWARDWith all studies, the research design is subject to certainlimitations, and our study is no different. For example, byintentionally using a questionnaire-based data collectiontool like TSES, we are opening ourselves to variousbiases of not only the target response pool (teachers),but also biases in our interpretation of the data. Whileteacher efficacy scales are widely used tools in educationresearch, we believe the incorporation of a factor thataddresses Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education,adopted within the last five years by New York State, canenrich the results.The goal of our Forte case study and future teacherefficacy work is to provide timely feedback that alsohelps us understand the intricacies of evaluatingeducation-based outcome variables. As we work withprimary, middle, and high schools in New York City,we aim to build a replicable efficacy model that schooladministrators can use in their schools to nurture teachersense of efficacy and thus student achievement.There is an established positive correlation betweenteacher sense of efficacy and student achievement.Teacher sense of efficacy does not manifest without thesupport and guidance of effective leadership teams. Itis incumbent upon school leadership to design schoolprocesses and systems that nurture teacher confidenceand reify teacher success. At Forte, that work is done,in part, through a carefully constructed instructionalcoaching program that provides teachers withindividualized support.5

THE FORTE WAY: A COACHING CASE STUDY DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMICREFERENCESAdams, C. M., & Forsyth, P. B. (2006). Proximatesources of collective teacher efficacy. Journal ofEducational Administration, 44(6), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230610704828Anonymous Leadership 02. (2021, May 27). PersonalInterview [Online chat].Anonymous Teacher 13. (2021, May 27). PersonalInterview [Online chat].Anonymous Teacher 22. (2021, May 27). PersonalInterview [Online chat].Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifyingtheory of behavioral change. Psychological Review,84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033295X.84.2.191Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived Self-Efficacy inCognitive Development and Functioning. EducationalPsychologist, 28(2), 117–148. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2802 3Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise ofcontrol. W.H. Freeman and Company.Dembo, M. H., & Gibson, S. (1985). Teachers’ Sense ofEfficacy: An Important Factor in School Improvement.The Elementary School Journal, 86(2), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1086/461441Donohoo, Jenni, Hattie, J., & Eells, R. (2018, March).The power of collective efficacy. Educational Leadership,75(6), 40–44.Donohoo, J., O’Leary, T., & Hattie, J. (2020). The designand validation of the enabling conditions for collectiveteacher efficacy scale (EC-CTES). Journal of ProfessionalCapital and Community, 5(2), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-08-2019-0020Fives, H., & Buehl, M. M. (2009). Examining the FactorStructure of the Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale. TheJournal of Experimental Education, 78(1), 1Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Hoy, A. W. (2004).Collective Efficacy Beliefs: Theoretical Developments,Empirical Evidence, and Future Directions.Educational Researcher, 33(3), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033003003Ost, B. (2014). How Do Teachers Improve? The RelativeImportance of Specific and General Human Capital.American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(2),127–151.Siwatu, K. O. (2011). Preservice Teachers’ CulturallyResponsive Teaching Self-Efficacy-FormingExperiences: A Mixed Methods Study. The Journal ofEducational Research, 104(5), 360–369. , K. O., Putman, S. M., Starker-Glass,T. V., & Lewis, C. W. (2017). The CulturallyResponsive Classroom Management Self-EfficacyScale: Development and Initial Validation.Urban Education, 52(7), 862–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085915602534Stewart, T. (2012). Classroom teacher leadership:Service-learning for teacher sense of efficacy andservant leadership development. School Leadership &Management, 32(3), 233–259. nen-Moran, M., & Barr, M. (2004). FosteringStudent Learning: The Relationship of CollectiveTeacher Efficacy and Student Achievement. Leadershipand Policy in Schools, 3(3), 189–209. -Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacherefficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teachingand Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. rs, C. A., & Daugherty, S. G. (2007). Goalstructures and teachers’ sense of efficacy: Their relationand association to teaching experience and academiclevel. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 81Goddard, R. (2002). A Theoretical and EmpiricalAnalysis of the Measurement of Collective Efficacy:The Development of a Short Form. Educational andPsychological Measurement, 62(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131644020620010076

Sabrina Abbamonte is a Bachelor of Science student and apart of the fast-track masters program at St. John's University. She is currently studying Marketing for her undergraduate degree and Marketing Management for her graduate degree at the Tobin College of Business. Sabrina can be reached at sabrina.abbamonte18@stjohns.edu.