Transcription

PPW workshop, CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012WHEN PARTICIPATING IN THE SAME EVENT DOES NOT MEAN SHARING THE SAMECOLLECTIVE ACTION REPERTOIRERelationship of survey respondents at the Dakar WSF to protest practices: How familiar arethey with them? How effective do they judge them to be? Are they willing to say so?Johanna Siméant, with Ilhame Hajji (CESSP-Paris 1)jsimeant@univ-paris1.frAfter a presentation of the collective survey from which this communication is drawn, our purpose here isto consider how World Social Forum participants relate to protest practices in terms of both theirexperience of these practices and how effective they judge them to be. The difficulties involved inconducting this type of research in world social forums—as opposed to in more local forums—areconsiderable given the diversity of the participants’ nationalities and of their specific protest traditionsand experiences. We shall start by exploring professed forms of political protest and how this latter islinked to a number of variables, then follow that with an examination based on a multiple correspondenceanalysis (MCA), which is more consistent with a multifactorial conception of commitment than a ceterisparibus model, which would be unwieldy in an international militant event. MCA, and its ability tocondense information, enables a full, visual, and summarized view of a population and its diversity, andallows polarities within it to emerge rather than to be posited; it is then possible to draw up ahierarchical classification, which, projected onto a factorial map, makes it easier to identify affinitiesbetween modes of action and subgroups within the population participating in this militant event.1. Surveying an international militant eventSocial forums and other alterglobalization mobilizations have been, in the past ten years, thesubject of numerous international surveys, and these have increased our knowledge of thesocial properties and political preferences of their participants. Compared to regional ornational forums and other gatherings, however, there has been much less work done on worldsocial forums (WSFs) because the linguistic and social diversity of WSF participants makes itdifficult to build equivalencies between country-dependent individual characteristics. Justcomparing an American with a French graduate can be problematic, and it is even morecomplicated to compare the simple fact of knowing how to read between a small farmer fromMali and one from France, for instance.This survey1 builds on earlier work on the sociology of alterglobalization,2 theinternationalization of activism3 and of different types of activism in Africa.41Facilitated by Johanna Siméant (CESSP), Marie-Emmanuelle Pommerolle (CESSP), Isabelle Sommier(CESSP), Séverine Awenengo (CEMAF-Paris 1), and Hélène Charton (CEAN-Bordeaux).2See the work done under the direction of Isabelle Sommier and Eric Agrikoliansky, Radiographie dumouvement altermondialiste, Paris, La dispute, 2005.3SIMEANT Johanna, “Committing to Internationalisation: Careers of African Participants at the World SocialForum”, Social Movement Studies: Journal of Social, Cultural and Political Protest,DOI:10.1080/14742837.2012.714125, 2012.4It also provides a benchmark for the survey conducted during the World Social Forum held in Nairobi in 2007,which gave rise to several publications, including POMMEROLLE Marie-Emmanuelle, SIMEANT Johanna(dirs.), Un autre monde à Nairobi, Paris, Karthala, 2008 and POMMEROLLE Marie-Emmanuelle, SIMEANTJohanna, “African Voices and activists at the WSF in Nairobi – the uncertain Ways of Transnational African1

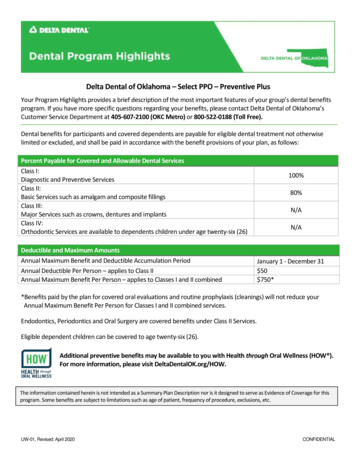

PPW workshop, CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012The objectives of the Dakar WSF survey (February 5 to 11, 2011) were to conduct a wideranging quantitative survey with more sociographic elements than used so far in internationalmilitant events, which would make it possible both to reflect on a number of sub-populations(French participants at the WSF, Senegalese participants, African participants, etc.) and tocompare national groups attending the WSF. This was done via a 56-question questionnairesubmitted in five languages (French, Spanish, Portuguese, English, and Wolof),5administered6 and self-administered among more than 1,100 persons in the forum workshops,as well as at other forum venues so as not to have an overrepresentation of the “studious”participation at the event. It was the first international survey of this kind to factor in so highlythe linguistic diversity of the survey situation by providing the possibility of administering thequestionnaire in a local language—which, incidentally, testified to the positive perception ofthe survey during its administration.Table 1: Data on the 2011 Dakar WSF SurveyThe surveyDatabase acquiredSociographic n level48 researchers and young researchers5 disciplines1 8-page questionnaire and 56 questions. in 5 languages administered and self-administered among 1,100 individuals1,169 questionnaires captured24% administered and 75% self-administered (NR 1%)Languages: English 17.5%, Spanish 8%, French 67%,Portuguese 4.5%, Wolof 2.5%- 305 variables- Gender: Men 56.5%, Women 40%- Age: Average: 40, median 38 [17;80]; 1st quartile 28years old; 3rd quartile 52 years old- Nationalities: Majority: French (20%) and Senegalese(28%); all other countries between 0.2% and 4.5%.Continents: Africa 50%, Europe 32%, Americas 12.5%,Asia 2.25%, Oceania 0.25%, NR 3%- 39.5% management and higher intellectual occupations(many were community organization managers andprofessors)- 24% intermediate professions- 12% high-school and university students- 17.5% teachers- 9.5% retirees- 47% full-time job- 6.5% unemployed- 11.5% part-time job- 1.6% stay-at-home- 8% temporary job- 16% high-school or universitystudents77.5% university graduates including 52.5% Masters or PhDs-Activism), in Jackie SMITH, Scott BYRD, Ellen REESE, & Elizabeth SMYTHE (eds.), The Handbook of WorldSocial Forum Activism, Paradigm Publishers, 2011, p. 227-247.5The English version of the questionnaire is attached to this communication as an appendix.6The questionnaire was designed to be both self-administered and administered because, among others, someonespeaking only Wolof would most likely not know how to read.2

PPW workshop, CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012OrganizationsA majority of the respondents (69.5%) stated they were there torepresent an organizationIdentification with theStrong 51% Reasonable 31% Partial 14%alterglobalizationmovementReligion- 60% of respondents stated that they belonged to a religion,the majority to Islam (34%) and to Christianity (22.5%)- Belief: 64% of WSF respondents stated that they werebelievers, 9.5% agnostics, and 20% atheists and nonbelievers2. What do we know about how familiar alterglobalization militants are with protestpractices?The work accomplished over more than 10 years on the alterglobalization movement has as awhole provided numerous data making it possible, among others, to identify for participantsthe (European, national or world) social-forum7 organizations with which they are associated,their sociographic properties8 (considered in particular as belonging to the “new middleclasses” and as “rooted cosmopolitans”9), the networks they belong to, the organizations’ rolein their mobilization, and their conceptions of democracy.10 Quantitative11 and qualitative12work on world social forums has in particular underscored the possible on-site effects of theinternational division of militant work.On the other hand, despite the fact that alterglobalization militants are considered a verypolitically active population, their relationship to protest practices, whether professed orjudged in terms of ethics and efficiency, is among the less developed quantitative aspects thathave been studied.For instance, the work drawn from the DEMOS surveys conducted in European SocialForums (ESFs), those held in Florence and Athens in particular, scarcely examined this aspectat all. At most, participation over the previous year in an alterglobalization-type event ismentioned. Whether considered from a quantitative or a qualitative angle, this questionremains underdeveloped and underexploited compared to the question of the relationship todeliberative practices and democratic participation.13 Although the DEMOS survey included a7FISHER Dana R., STANLEY Kevin, BERMAN David, NEFF Gina, “How Do Organizations Matter?Mobilization and Support for Participants at Five Globalization Protests”, Social Problems, Vol. 52, No. 1 (Feb.,2005), p. 102-121.8AGRIKOLIANSKY Eric, SOMMIER Isabelle (ed.), Radiographie du mouvement altermondialiste, Paris, Ladispute, 2005.9DELLA PORTA Donatella (2005) 'Multiple Belongings, Flexible Identities, and the Construction of 'AnotherPolitics': Between the European Social Forum and Local Social Fora', in D. della Porta and S. Tarrow (eds.)Transnational Protest and Global Activism. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.10DELLA PORTA DONATELLA (ed.), Democracy in social movements, New York : Palgrave Macmillan,2009.11KWON Roy, REESE Ellen, ANANTRAM Kadambari Core-Periphery divisions among labor activists at theworld social forum Mobilization: An International Journal 2008 13(4): 411- 3012POMMEROLLE Marie-Emmanuelle, SIMEANT Johanna (dirs.), Un autre monde à Nairobi, Paris, Karthala,2008 ; POMMEROLLE Marie-Emmanuelle, SIMEANT Johanna, « Voix africaines au Forum Social Mondial deNairobi - les chemins transnationaux des militantismes africains", Cultures et Conflits, été 2008, 70, p.129-149.13Cf. DELLA PORTA Donatella (ed.) Democracy in social movements. Basingstoke New York : PalgraveMacmillan, 2009 et DELLA PORTA Donatella (ed.) Another Europe: conceptions and practices of democracyin the European social forums. London ; New York : Routledge, 2009.3

PPW workshop, CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012set of questions covering the relationship to these democratic practices,14 this aspect appearsto have been underexploited in the work drawn from the database resulting from the survey.Even in the work focusing more on participation and its determinants,15 participation seems tobe disconnected from its concrete manifestations.There are two exceptions to this general trend: an article following a survey conducted duringthe Evian G8 Summit,16 and a chapter discussing the data collected during the ESF held inSaint-Denis (France),17 both events having been held in 2003. Both the article and the chapterraised a series of questions on the protest practices used by the respondents by asking themwhether they participated in these types of practices to have their voice heard and whetherthey were prepared to do so. What is interesting in this formulation is that it avoids purelyabstract judgment on the practices by asking the participants if they had actually resorted tothem and if they would be prepared to do so. The list included 14 items: petitions,demonstrations, study groups, product or country boycotts, leaflets, strikes, symbolic actions,traffic obstruction, occupation, resisting against law-enforcement authorities, fasting/praying,damage to property, hunger strikes, and physical pressure.These two studies (n 2280 at the G8 and n 2198 at the ESF) provided a hierarchy of protestpractices very closely associated with their overall population (even though the G8 populationseems somewhat more radical and protest-oriented):-Of the respondents, 90% to 92% stated that they had already participated in a strike ordemonstration.-Between 52% and 74% of the respondents stated that they had already taken part instudy groups, boycotts, symbolic actions, strikes, and leaflet distribution.-As for traffic obstruction, occupation of buildings, and resisting against lawenforcement authorities, between 48% and 32% of respondents at the G8 and between26% and 40% of those at the ESF stated they had taken part in these.-Between 2% and 11% of respondents claimed to have participated in fasting orpraying, hunger strikes, physical pressure on a person, or damage to property.The work done on the demonstrators at the G8 has provided an indicator of activists’ protestpotential by cumulating their answers to the protest items.18 This has made it possible todistinguish four protest-potential quartiles and to display the associated sociographicproperties, underscoring the population’s male character and the fact that it is those who have14“Tried to persuade someone to vote for a political party”, “Worked in a political party”, “Signed apetition/public letter”, “Attended a demonstration”, “Handed out leaflets”, “Took part in a strike”, “Practicedcivil disobedience”, “Took part in non-violent direct actions”, “Boycotted products”, “Participated in culturalperformances as a form of protest”, “Took part in an occupation of a public building”, “Took part in anoccupation of abandoned homes and/or land”, “Took part in a blockade”, Used violent forms of action againstproperty”, “Other”15SAUNDERS Clare, ANDRETTA Massimiliano, “The Organizational Dimension. How organizationalformality, voice and influence affect mobilization and participation” dans DELLA PORTA Donatella (ed.)Another Europe: conceptions and practices of democracy in the European social forums. London ; New York :Routledge, 2009.16FILLIEULE Olivier, BLANCHARD Philippe, AGRIKOLIANSKY Eric, BANDLER Marko, PASSYFlorence, SOMMIER Isabelle, « L’altermondialisme en réseaux. Trajectoires militantes, multipositionnalité etformes de l’engagement : les participants du contre-sommet du G8 d’Évian », Politix, 2004, 17 (68), p. 13-48.17COULOUARN, Tangui, JOSSIN, Ariane, « Représentations et présentation de soi des militantsaltermondialistes », in AGRIKOLIANSKY Eric, SOMMIER Isabelle (dir.) Radiographie du mouvementaltermondialiste, La Dispute 2005, p. 127-155.18Assigning a 2 value for effective participation and a 1 value for potential participation.4

PPW workshop, CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012conventional political skills who are most inclined and able to express themselves.19 It isamong these too that the greatest number of the movement’s leaders is found.20Coulouarn and Josselin, taking up the distinction of action agendas proposed by Uehlinger21and Fuchs,22 posit three types of agenda:- a demonstrative agenda, “legal and non-violent,” grouping those who refuse topractice “all actions covered by the confrontational and political-violence agenda”;- a confrontational agenda, “illegal and non-violent,” designating “those who only refuseto use means of action from the political-violence agenda”- the political-violence agenda (illegal and violent): “those who state that they havepracticed or are prepared to use at least one of two modes of action from the politicalviolence agenda” (144)Appropriately, they distinguish judgment on illegal and violent practices, and show that apractice does not have to be judged as efficient to be practiced.Jossin and Coulouarn then examine the composition of the three groups most marked by theuse of these practices and by the rejection of such practices. Gender appears as a cleardifferentiation factor in using violent and illegal practices. Otherwise, those included in thepolitical-violence group are characterized by a slightly lower education level and by a largershare of unemployed persons. This group is more marked by a relationship to unionmovements and to extreme left/right-wing positioning. It seems more strongly marked by apreference for radical change ideologies. The demonstrative group appears closer to the NGOworld. Finally, identification with the alterglobalization movement is also a factor inacceptance of violent or illegal means of action.There are two problems in this study, which happens to be one of the very rare ones available:on the one hand, there is a prejudicial error where absence of response is aggregated withrefusal to practice a particular mode of action; the other problem is that the three groups wereposited instead of letting a potentially different structure emerge for the world of thesepractices, based on the respondents. What, for instance, is said about variations in theattraction to protest practices depending on the nationality? Though a march is consideredroutine and conventional in the sociology of social movements, what is learned about what amarch means in such or such African country? 23 This question, which may be of lesserimportance in European social forums, becomes particularly acute in a world social forum.This is precisely the question that is difficult to answer, given the small number of studiesraising it in situations of multinational and multilinguistic surveys.In fact, the only data collected at world social forums related to protest practices is whetherrespondents have taken part in a demonstration in the previous 12 months24 (16.8% of19FILLIEULE Olivier et al, p.Ibid.21UEHLINGER Hans-Martin, Politische Partizipation in der Bundesrepublik. Strukturen uyndErklärungsmodelle. Opladen: Westdetscher Verlag, 1988.22FUCHS Dieter, “The normalization of the Unconventional. Forms of Political Action and New SocialMovements”, in Gerd Meyer, Ryszka Francisek (dir.), Political Participation and Democracy in Poland andWest Germany, Varsovie, Wydawcva, 1991.23Sur ce point, je me permets de renvoyer à SIMEANT Johanna, «Oh no ! Let’s march but not riot!” Streetprotests in Bamako during the years 1992-2010”, communication à l’European Consortium for African Studies(ECAS 4), Uppsala, panel on Social movements, 17 juin 2011, 19 p24REESE, Ellen, Christopher CHASE-DUNN, Kadambari ANANTRAM, Gary COYNE, MatheuKANESHIRO, Ashley N. KODA, Roy KWON, and Preeta SAXENA. 2008. “Research Note: Surveys of WorldSocial Forum Participants Show Influence of Place and Base in the Global Public Sphere.” Mobilization, 2008,13 (4): p. 435.205

PPW workshop, CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012respondents at the 2005 WSF stated no participation, and 34% at the 2007 WSF stated thatthey had had none, this latter having been first-time participation at a social forum for 80.4%of the respondents there).We thus have either rich, qualified work covering a relatively limited geographical area inwhich the national-origin issue is scarcely considered, or work covering a more multinationalpopulation but which gives little indication of what characterizes potentially very diversifiedrelationships to protest practices. Can we even assume that participating in a demonstration ora strike has the same meaning in very distant contexts? If not, to what does this diversity inprotest practices refer and how can it be explored?This is the issue that we have chosen to address by raising this question on the populationsurveyed at the WSF.3. Familiarity with protest practices among the respondents at the Dakar WSFWhen developing the questionnaire, we reproduced the questions used by Sommier andAgrikoliansky regarding familiarity with a number of protest practices and how thesepractices are judged.25 We added 4 practices that were not included in this analysis:-participating in a “national day of mobilization,” a form of mobilization not alwaysdirectly related to protest that seemed to us particularly supported by activists in thecountries of the South, especially in the development-aid sector“support financially an organization”“activist/militant consumption (local, fair, organic products),” or responsibleconsumption“boycott elections”Along with the 4 additional items, certain formulations were not reproduced in exactly thesame way: for instance, we distinguished collective prayers and religious gatherings, on theone hand, and fasting and hunger strikes on the other, whereas fasting and hunger strikes weretwo distinct categories in the previous survey.26 Finally, we added participating “in othersymbolic actions” to account for other potentially corresponding practices.Here is the outcome of the frequency distribution of participation in these practices among thesurveyed population (see Table 3 page 9):--As in the ESF and G8 surveys, petitions and demonstrations are at the top of the scaleat 74%, but exceeded by participation in study or discussion groups.Participation in a national day of mobilization and financial support to an organizationare practices claimed by two-thirds of the sample, along with participation in othersymbolic actions. Leaflet distribution and strikes, as well as other symbolic actions,are claimed by more than half of the respondents but in a lesser proportion than in theEuropean surveys.The three practices that were claimed by between 32% and 48% of the G8 respondentsand by between 26% and 40% of the ESF respondents (traffic obstruction, occupying25AGRIKOLIANSKY Eric and Isabelle SOMMIER (eds.), Radiographie du mouvement altermondialiste, lesecond Forums social européen, Paris, La Dispute, 2005.26This is precisely because people who use fasting and hunger-strikes also play on the porosity between the twomodes of action. See Siméant Johanna, La grève de la faim, Collection Protester, Presses de Sciences Po, 2009.6

PPW workshop, CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012-buildings, and resistance against law-enforcement authorities) are down in this sampleto between 28% and 29%, with traffic obstruction at a much lower rate.27On the other hand, use of collective prayer and religious gatherings is claimed by 34%of the respondents.Finally, only 5 practices, down from 7 in the preceding surveys, are claimed by morethan 50% of respondents.In addition, the number of persons indicating that they had never participated in analterglobalization event in the previous ten years is 33% of the respondents, which is one ofthe lowest rates ever in these surveys (to be compared with 80% of first-time participants at aWSF in Nairobi).28Finally, regarding participation in a demonstration in the previous year, this is what therespondents say:Table 2 – Have you taken part in the following events in the past twelve months ? (n 1069)OUINONNRa. Protests/events in your country against your governments’ policy?58.1926.2915.53b. Protests, movements against international or regional institutions30.3137.7931.9(G20, IMF, etc.)c. Local or regional social forums on continental themes46.2131.9921.8What can account for the differences in familiarity with protest practices and in how they arejudged? We have chosen to systematically produce cross-tabulations between the results ofthis table and three variables: for the moment, 1) nationality (grouped by continent andconcentrating on the three continents that showed sufficient numbers to make thesecalculations), 2) gender, and 3) education level, regrouped as lower than a high-schooldiploma and as equal to or higher than a high-school diploma. The result is indicated in Table4 below.This makes it possible to reflect on the properties of modes of action by distinguishing thosethat seem particularly linked to one or several of the three variables. We can thereforedistinguish:- “gendered” modes of action: responsible consumption (F ) and resisting against lawenforcement authorities (M ), as well as petitions, damage to property, physical pressure on aperson, boycott of products/countries, of elections, hunger strike/fasting- modes of action related to education level: petitions, responsible consumption, othersymbolic actions, strikes, leaflets, boycott of products/countries, collective prayers orreligious gatherings, resistance against law-enforcement authorities, traffic obstruction,occupation of buildings, hunger strikes/fasting, as well as demonstrations, day ofmobilization, refusing to pay taxes, physical pressure29- nationality-related modes of action: petitions, demonstrations, strikes, leaflets, boycott ofproducts/countries, collective prayers or religious gatherings, resistance against lawenforcement authorities, traffic obstruction, occupation of buildings, hunger strikes/fasting,27It is not impossible, however, that the slightly different formulation of our question, which added blocking oftrains, may have impressed some of the respondents.28This first-time participation is significantly related to the fact of being African. The p-value is 1.787441E-9. Itis not impossible, however, that our survey, which was conducted not only within the workshops but also outsideof them, may have “caught” less studious participants than those surveys focused on the workshops.29The last case is complex, because graduates tended more to either say they have practiced it or that they areopposed to it, while those with lower education levels showed up more in the no-reply category.7

PPW workshop, CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012refusing to pay taxes, exercising physical pressure on a person,30 as well as boycott ofelections- modes of action related to education level AND gender-related: responsibleconsumption, resistance against law-enforcement authorities, as well as petitions, boycott ofproducts, shops, countries, hunger strike/fasting, physical pressure- nationality- AND gender-related modes of action: not as clear, but boycott elections anddamage to property- nationality- AND education-level-related modes of action: strikes, leaflet distribution,collective prayers/religious gatherings, traffic obstruction, occupation of buildings, as well asdemonstrations, hunger strikes, refusing to pay taxes, physical pressure- nationality- AND education-level- AND gender-related modes of action: responsibleconsumption, resistance against law-enforcement authorities, as well as petitions, boycott ofcertain products/shops/countries, hunger strikes/fasting, physical pressureOn the other hand, several modes of action come up as neutral under the variables used so far:participating in study or discussion groups, participating in a national day of mobilization (forwomen, against AIDS, etc.), supporting an organization financially: these are the three modesof action that we had added, the confrontational dimension of which is very low. That thesemodes of actions should appear here as scarcely divisive is an interesting result in itself foralterglobalization forms of mobilization; they are undoubtedly better channels for adaptingforms of mobilization to forms of protest. We can see here that they can be appropriated ascutting across a variety of militant sensitivities in the realm of alterglobalization, and that theyalso refer to practices peculiar to the development-aid sector and to perceived traditions fromthe South (promotion of tontines, in particular).3130It is important not to have a binary reading of this link among variables. In this specific case, Europeans areoverrepresented among those who claim they are opposed to physical violence on persons, and Africans areoverrepresented in no-reply to this question.31On this point, see the work of Emmanuelle BOUILLY, “Mobiliser sans protester. Actions non-protestataires,techniques d’enrôlement et répertoires de mobilisation développés par les leaders associatives au Sénégal”,annual seminar “Femmes, Genre et Mobilisations collectives en Afrique”, CEMAF, March 22, 2012.8

PPW workshop, CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012No,But Iwould beready todo itNo,And Irefuseto do 126,94Yes,I havei. Participatein discussion or reflection groupsb. Sign petitionsc. Participate in a protestr. Participate to a national day of mobilization (Women’s day, fight against Aids, etc.)p. Support financially an organization (contributions, donations )q. Responsible consumption (local, fair, organic products)s. Participate in other symbolic actionsg. Participate in a strike32m. Distribute leafletsf. Boycott certain products/shops/countriese. Participate in collective prayers or religious gatheringsk. Oppose and resist police forcesl. Participate in acts that block the traffic (sit-in, blocking of trains, etc.)j. Participate to sit-ins of buildings (factory, school, etc.)a. Boycott electionsh. Participate in a hunger strike or a fasto. Refuse to pay taxes, bills from state companiesd. Cause damage to material goods (riots)n. Put physical pressure on someone75,1274,37Table 3 – Hierarchy of recourse to protest practices among the respondents at the Dakar WSF (n 1069)32The original (and wrong) formulation was “pamphlets” in the English questionnaire, but “tracts” in French. The line in yellow indicates the limit of the 50%.9

PPW workshop, CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012No,Yes,I havei. ParticipateBut I wouldbe ready todo itNo,And Irefuse todo itNAGenderEducation levelNationalityin discussion or reflection groupsb. Sign petitionsc. Participate in a protestr. Participate to a national day of mobilization (Women’s day,fight against Aids, etc.)p. Support financially an organization (contributions,donations )q. Responsible consumption (local, fair, organic products)s. Participate in other symbolic actionsg. Participate in a strikem. Distribute leafletsf. Boycott certain products/shops/countriese. Participate in collective prayers or religious gatheringsk. Oppose and resist police forcesl. Participate in acts that block the traffic (sit-in, blocking oftrains, etc.)j. Participate to sit-ins of buildings (factory, school, etc.)a. Boycott /Yes inNA/Dip-/64,1713,472,7119,64/60,0613,844,8621,23

national forums and other gatherings, however, there has been much less work done on world social forums (WSFs) because the linguistic and social diversity of WSF participants makes it . CUNY, Sept 20th, 2012 2 The objectives of the Dakar WSF survey (February 5 to 11, 2011) were to conduct a wide- . Education level 77.5% university .