Transcription

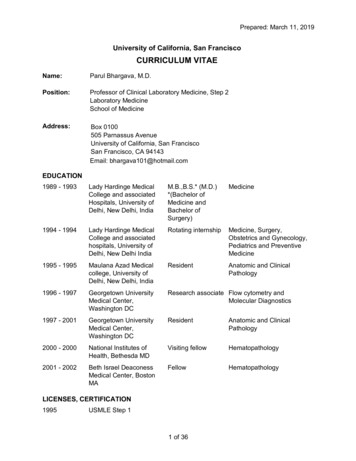

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEARNINGVolume 11Article: LC04-0030-2004Reforming “Traditional” Teaching Methods in InService Training Programs for Early ChildhoodTeachersAn Action Research ProjectVassiliki Riga, Scientific Associate- Researcher, Technological EducationalInstitution, Hellenic Open University, GreeceKafenia Botsoglou, Lecturer in Early Childhood Education, Department of SpecialEducation, University of Thessaly, GreeceLearning Today: Communication, Technology, Environment, SocietyProceedings of the Learning Conference 2004

International Journal of LearningVolume 11www.LearningConference.comwww.theLearner.com

This journal and individual papers published at www.Learning-Journal.coma series imprint of theUniversityPress.comFirst published in Australia in 2004/2005 by Common Ground Publishing Pty Ltd atwww.Learning-Journal.comSelection and editorial matter copyright Common Ground 2004/2005Individual papers copyright individual contributors 2004/2005All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permittedunder the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permissionfrom the publisher.ISSN 1447-9494 (Print)ISSN 1447-9540 (Online)The International Journal of Learning is a peer-refereed journal published annually. Full papers submitted forpublication are refereed by the Associate Editors through an anonymous referee process.Papers presented at the Eleventh International Literacy and Education Research Network Conference onLearning, Cojímar Pedagogical Convention Centre Havana, Cuba, 27-30 June 2004

EditorsMary Kalantzis, Innovation Professor, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia.Bill Cope, Common Ground and Visiting Fellow, Globalism Institute, RMITUniversity, Australia.Editorial Advisory Board of the International Journal of LearningMichael Apple, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA.David Barton, Lancaster University, UK.James Paul Gee, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA.Brian Street, King's College, University of London, UK.Kris Gutierrez, University of California, Los Angeles, USA.Scott Poynting, University of Western Sydney, Australia.Gunther Kress, Institute of Education, University of London.Ruth Finnegan, Open University, UK.Roz Ivanic, Lancaster University, UK.Colin Lankshear, University of Ballarat, Australia.Michele Knobel, Montclair State University, New Jersey, USA.Nicola Yelland, RMIT University, Australia.Sarah Michaels, Clark University, Massachusetts, USA.Paul James, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia.Michel Singh, University of Western Sydney, Australia.Peter Kell, University of Wollongong, Australia.Gella Varnava-Skoura, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece.Andeas Kazamias, University of Wisconsin, Madison, USAAmbigapathy Pandian, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia.Carey Jewitt, Institute of Education, University of London, UK.Denise Newfield, University of Witwatersrand, South Africa.Pippa Stein, University of Witwatersrand, South Africa.Zhou Zuoyu, School of Education, Beijing Normal University, China.Wang Yingjie, School of Education, Beijing Normal University, China.Olga Lidia Miranda, Researcher, Institute of Philosophy, Central Institute ofPedagogical Sciences, Cuba.Mario Bello, University of Science, Technology and Environment, Cuba.Miguel A. Pereyra, University of Granada, Spain.Daniel Madrid Fernandez, University of Granada, Spain.

Reforming “Traditional” Teaching Methods in In-ServiceTraining Programs for Early Childhood TeachersAn Action Research ProjectVassiliki Riga, Scientific Associate- Researcher, Technological Educational Institution, Hellenic OpenUniversity, GreeceKafenia Botsoglou, Lecturer in Early Childhood Education, Department of Special Education, University ofThessaly, GreeceAbstractThe study is a six-year action research project about in-service for Early Childhood Education (ECE) teachers.The aim of our research project is to investigate new teaching approaches in teacher’s education thatencourages their professional development and life long learning. We used qualitative interviews and directobservations in order to evaluate the adopted teaching model namely experiential learning and teacher’s viewsabout their new learning experiences. Statistical analysis was conducted on questionnaire data. Interpretiveinterviews were analysed and observation of the participants took place during the courses. The findingsdemonstrate that ECE teachers after the training program adopted new perceptions about their personal andprofessional status as educators. They started to express greater pleasure and personal interaction with theirstudents and exhibit a greater appreciation for their teaching style. Finally, teachers pointed out that a trainingcourse can only be effective when they are given the opportunity to be actively involved in the learning process.Keywords: In-service education, Professional development, Experiential learningIntroductionInternational economic, technological, social andcultural development renders it necessary to reformadult education for Early Childhood Education(ECE) teachers so as to acquire more knowledge andskills respecting their personal and professionalneeds.Acquisition of qualifications and knowledge forECE teachers is predominantly obtained from inservice training that occurs after five years ofprofessional experience. Noyé & Piveteau (1997)suggest the structure of this type of education aimsto fulfill three objectives: Furthering knowledge about general education Acquisition of new technical knowledgeinvolved in professional employment Acquisition of basic social skills (planning,alternative solutions, adaptability and growth ofinterpersonal relations).Eurydice (1995) adds that in-service trainingprograms also aim at improving professional skillsand capacities by: Updating basic knowledge about teachingtechniques and subjects skills Learning new teaching methods for specificsubject areasA two-year in-service training program is providedat the Marasleio Teacher Training College (n. .gr), for ECE teachers under theage of 40 with at least five year’s teachingexperience. The training focuses on research and thescientific study of subjects relating to psychology,education, and primary education policy. Thisprogram lasts for four (4) semesters and teachersparticipate after having taken written exams. Theyare exempt from their instructive and administrativeduties while in the program.Literature ReviewExperiential Learning in Adult EducationInitial knowledge, values, skills and experiencesacquired during an ECE teacher’s initial trainingoperate within a social framework (Jarvis, 1987) thatinfluences their educational process in the preschooleducational system.Traditional pedagogical methods are frequentlyused in educating ECE teachers. The results of thiskind of education are evident from an ECE teacher’sstyle of teaching and the way he/she facilitateslearning with children. For example, they organizetheir classroom with traditional activity areas suchas: surgery, cookery, and constructive materials andafterwards remain inactive. They simultaneouslyapply the same activity to all the children and ignorethat all the children do not have the same interests,possibilities and rates of development (Eadap,2003).International Journal of Learning, Volume 11 www.Learning-Journal.comCopyright Common Ground ISSN 1447-9494 (Print) ISSN 1447-9540 (Online)Paper presented at the Eleventh International Literacy and Education Research Network Conference on Learning.Cojímar Pedagogical Convention Centre, Havana, Cuba, from 27-30 June 2004 www.LearningConference.com

International Journal of Learning, Volume 11Future ECE teachers play a crucial role inincreasing the quality of early childhood education.Professors are called upon to not only teach newknowledge but also plan, organize and evaluate theirECE teacher’s future educational work according tostudent’s needs and the current social context.ECE university professors need to take intoconsideration the skills and experiences of adultstudents in teaching new subject matter. Therelationship that these professors develop with theirstudents occurs within the process of mutualdecision-making, common planning and evaluationof the program’s content and objectives. Aprofessor’s authoritative status is intended to giveway to importance of collaboration and creativity.Researchers stress a need for reforming these“traditional” teaching methods in universities.Lectures only seem effective for students in that theyimprove their ability to collect information and giveoral presentations (Chickering, 1997, Pugsley &Klayton, 2003). It is very difficult for the professorto introduce new learning techniques, styles andprocesses into a traditional system of education.Some of them try to continue their life long learningby reflecting on their educational experience, theirattendance at international conferences ofcollaboration and by assessing their own attempts atintegrating newer teaching methods.Education in formal environments differsqualitatively from out of university educationnamely «social education» (Gotovos, 1985). Theindividual, the social framework and the process d approaches of education. The firstapproach in training ECE teachers is competitive,mainly theoretical and without a clear sense ofpragmatic application. The second teachingapproach is cooperative, is not limited to just hightheory and is situated within the field of practice(Resnick, 1987).We planned a six-year research project based onthe assumption that teaching is a method thatfacilitates learning (Jarvis, 1995). The aim of ourstudy was to first develop an experiential learningstyle for ECE teachers during an in-service program,and secondly to explore how adult ECE learnersperceive this experiential learning style. A lot ofeducation theorists (Kolb, 1984, Keeton, 1982,Rogers, 2001) have maintained that learning issupported, socialized and nurtured throughexperience.We decided to stop using a “lecture style ofteaching” and to adopt a different method that takesinto consideration the ECE teacher’s beliefs and thatstrongly emphasizes putting theory into action(Vratsalis, 1996). Within this new teaching approachwe reinforced that informal learning is an essentialcomponent in order to improve ECE teacher’spersonal and professional skills. This pedagogicalshift is based on an experienced-participative224teaching method. It is a way to translate theoreticalprinciples into action (Torkington & Landers, 1995)and favours research and challenge despite passiveacceptance.Consequently, the theoretical background of thecourse is no longer based on academic lectures, butinstead it results from the experienced exercises ofthe student’s personal views of his/her professionaland personal life (Boud & Walker, 1993). Thismodel emphasizes active and empirical learningrather than teaching. Practice is, thereby, thefundamental principle through which theory isunderstood.According to Sfard (1997) the active orparticipative learning models differentiate learninginto a traditional cognitive model the acquisition ofknowledge and meanings and a participativeapproach centered within learning through practice.Cognitive learning is a group of activities that takesplace inside an individual’s brain. In participativelearning, however, human activity emerges from asocial-cultural framework. Social interaction isconstituted by adults who find themselves in a grouplearning process that transcends one’s owneducational personal framework, abilities or skills.Participative learning stresses that adults learnthrough the analysis of participating in socio-culturalactivities (Rogoff, 1990). Participative learning isefficacious because students can check the contentof their learning and adjust it based on theirexperience (Schof, 1987). Professors, meanwhile,share “power” and control with students by adoptinga cooperative and participative perspective toeducation (Eadap, 2003).According to the experiential–participative modelof teaching, the largest portion of learning resultsfrom student involvement. An individual isphysically, emotionally and mentally influenced bythe learning process. Adults begin to learn fromwhat they feel and see. In living with new situations,adult learners face problems by experientiallylearning to adapt and cope with situationalexperiences (Tsay, 1998). By connecting newexperiences with previous ones, learners findthemselves critically reflecting upon theirexperiences with people who hold distinctivelydifferent positions from themselves by using newlyemerging criteria for evaluating and learning(Rogers, 2001).The aim, therefore, of experience-centeredteaching is not the exact transfer of knowledge andtheories to the professional, but instead the inquiringattitude from students about their continuous selfassessment of instructive actions.MethodWe formulated our research question after observingan increase in attendance and interest by teachersduring participative oriented teaching courses and

Reforming “Traditional” Teaching Methods in In-Service Training Programs for Early Childhood Teacherswe wondered will ECE teachers demonstrate aperceptual change in how they intend on teachingyoung children in their future classroom. Weanticipated that ECE teachers would in the futuremodify their traditional lecture style for anexperiential-participative teaching approach and thatthey will demonstrate this purposed shift in theirclassrooms.During our research project the ECE teacher’sparticipants continued to help us to restore ourresults and to infuse this new narrative back into thepaper. This action research project (Elliott, 1991)lasted six years. For three years at Athens Universitywe taught our ECE in-service training course1 byapplying the experiential method. The students whoattended the course amounted to 119 coming fromall over Greece and having at least a five-yearprofessional experience. During our courses weobserved certain student interaction, the nature ofcollaboration and the duration of involvement in anactivity.Among the techniques we used in order to collectthe data was participant observation through keepingnotes in a diary (Lapassade, 2000, Elliott, 1991,Jorgensen, 1989). We combined our directobservations with the content analysis of ourvideotaped courses (Fontaine, 1997). We triangulated this analysis by comparing the results ofthe two aforementioned techniques with thequestionnaires given to our students at the end of thecourse. All three of them focused on professorstudents interaction, student to student onstration of interest.As professors in the in-service training course forECE teachers we adopted the experimentalparticipative teaching method. Our content objectivewas concerned with teaching about the psychomotorskills of young children. Our teaching focusedmainly on the ECE teacher’s personality, feelingsand expectations about our course and notnecessarily on what they specifically will teachwhen they are be back in their classes. We made thisdecision because we believe that teacher’scommunicability, intuition, rhythm of teaching,sensitivity to non-verbal messages and creativity areessential to their teaching styles.In the first courses we emphasized a climate ofconfidence, safety and communication thatsupported educators who shared experiences andconcerns. We also tried to create a pleasant andhappy environment, because leisure during coursesis often cited as a goal for adult learners (Elsey,1986). We addressed to ECE teacher’s needs,desires and concerns. As a learning community wedecided on the course content and through the1With the term “course” we mean a series of lectures withdistinct goals.negotiation of various proposals we made anagreement that committed us to specific topic areas(Anagnostopoulou & Papaprokopiou, 2003).A different method of evaluation was also adoptedby the professors. ECE teachers were not evaluatedin the achievement of activities or in the acquisitionof new knowledge. Groups of ECE teachers insteaddecided the criteria for evaluation (Chretiennot,Hardy & Platone, 1989).The thematic units that ECE teachers suggestedmainly concerned personal needs rather than subjectmatter intended to improve their professional skills.Their expectations from the course were to feelpleasant, acquire new ideas and to feel free throughhaving a better relationship with themselves. Theyspecifically proposed the following thematic units,without knowing the professor’s intention about thecontent of the course: Activities in order to get to know each otherbetter Techniques in how to constitute and motivategroup work Activities for supporting group communication Awareness of one’s own body Improving self image and self respect Techniques for relaxation, breathing and speechtraining How body-language conveys meaning ActivatingimaginationandreinforcingcreativityA basic «tool» of the course was the ECE teacher’sbody. We began with concrete sensory-motoractivities that activate the body of students and helpin their awareness. We encouraged spontaneousactivity and movement in space, bodily contactbetween them and their team and we provided spacefor relaxation. We continued with the observationand the discussion of new experiences and feelingsthroughout the activities. In the end, we connectedthe new experiences with previous ones andacquired new knowledge about the psychomotoreducation of young children. In this way theknowledge was created through the transformationof experience (Kolb, 1984).During the courses we followed an activetechnique of teaching (Goguelin, 1987) based on theprinciple that somebody best retains what he/shelearns by combining action with speech and byclassifying new knowledge into his/her previousknowledge. This technique is not always easilyunderstood, and, yet, the participants in a trainingcourse are invited to appreciate the activity as ameans of acquiring knowledge.During the courses, the ECE teachers were eitherdivided in small groups or they carried outindividual experiential work according to ourinstructions. At the end of each activity there was afifteen- to twenty-minute discussion among all the225

International Journal of Learning, Volume 11participants, and an exchange of views andexperiences, led to a conclusionary analysis.Other techniques we used were: Simulated role-playing Case study work to analyze complicatedsituations learners would face at work (Walsh &Sheldon, 1991) Self-observation Projects at the end of the academic year thatasked that the group focus on preparing apsychomotor activity (Helm & Katz, 2002).At the end of the courses we observed through theexperience of concrete activities and their personalexperimentation that students abandoned theirpassive attitude toward learning and becamereflective researchers of their own teaching stylesand practices. They began to understand howimportant it is to experience a new pedagogicalapproach before applying it in the classroom.Our role during the courses had radically changed,from what we maintained in previous years. At thebeginning it was difficult to introduce experientialmethods and sometimes we regressed to traditionallecturing and to the security of the blackboard.These lecturing periods mainly occurred when wedid not feel we were in control of the students orwhen certain activities that we proposed did nothave the expected result.Our lack of experience in using these newtechniques of adult education became apparent fromthe start. Through our parallel participation in anadult education program and from the contentanalysis of our videotaped lessons, we began todevelop a “profile” to adopt a new role for ourselvesthat better coordinated our teaching within thecourse. The professor’s role can now be described asboth facilitator and mediator of knowledge.We were sincerely interested in: Understanding the personal and social history ofour students Assessing and benefiting from their previousexperiences Organizing the learning environment in order tofacilitate life-experienced learning (Kolb, 1984) Facilitating the dialogue between the students inorder to help them consider it part of thelearning procedure Choosing the appropriate course content thatwould address their needs Continuously evaluate the educational processWe tried hard to improve ECE teachers’interactions because when the levels of interactionare high, then learning increases (Tsay, 1998). Thislearning environment provided them with a friendlyatmosphere and a feeling of safety so as to expresstheir concerns and apprehensions.226ResultsECE Teachers’ Perceptions: At the End ofthe CoursesAt the end of each academic year, (1998-99, 199900 and 2000-01) we presented ECE teachers withanonymous questionnaires in order to evaluate ourcourse and to learn about their perceptions about ournewly introduced teaching method. Questionnairescontained both open and closed items and they askedabout course, content, teaching methods, teachingtechniques, course aims, interactions betweenprofessor and students, course evaluations of theprofessor and student, intentions in applyingconcrete activities in his/her personal andprofessional life etc.We collected 105 questionnaires from a totalpopulation of 119 students. The questionnaireconsisted of thirty questions. The answers of theopen questions were treated with content analysisand the closed ones with statistical analysis. Beloware listed only the answers we collected from thequestionnaire that are relevant to the questions ofour research.The findings reveal that the ECE teachers reflectedon the new learning process by suggesting:For example, to the open question “What new,unexpected elements did you find in the course?”they answered: active participation instead of simpleobservation interaction with our colleagues through theexercises immediacy within the relationship with ourprofessor activities for adults and not only for children the course is a change from traditional teachingand the everyday classroom routine using the body to experience things can lead tothe acquisition of knowledge relief from muscular pains balanced combination of practice and theoryTo the open question “What do you believe wouldmake the course more interesting?” they answered: evaluating an activity at the same time as thefunction that it serves organizing daily schedules for kindergartensand analyzing the schedule in a group videotaped psychomotor activities in variouskindergartens in Greece and abroad children’s participation in certain parts of ourcourses better facilities and equipment small number of students in the coursesTo the closed question “Which of the techniques Iused did you find effective?” the highest percentageof effectiveness was given to practical exercises

Reforming “Traditional” Teaching Methods in In-Service Training Programs for Early Childhood Teachers(30%), role-play (21%), discussion (16%), usingaudiovisual aids (14%), questions and answers(12%) and finally a very small percentage tolecturing(7%).Practical ual materialQuestions andanswersLecture21%Graph 1The techniques of teachingTo the open question “What do you intend to usein your Kindergarten as a result of what you learnedin the course?” they answered: I will not hesitate to let the children “turn theworld upside down” in order to experience it I will use relaxation, trust and communicationactivities in class It will help me deal with children in thekindergarten It will improve my respect for others andespecially toward children It helps me perceive some things related to thechildren in a different and in a more productiveway It assisted me in better understanding mychildren as more than just a brain It taught me to more effectively observechildrenTo the open question “Do you intend to use whatyou learned in the course in your personal life? Yesor no, and why?” they answered positively bystating: to relax to express myself spontaneously to try to communicate more effectively withothersto use movement in order to handle a lot ofproblems in my personal lifeto understand the way we react to the othersOnly 7% answered negatively to the questionabove for the following reasons: Because I came here for professional trainingthat I did not receive The content of teaching was not clear enough Because I prefer traditional lectures Because the courses were very fewIn response to a question with a multiple-choiceresponse set, student’s responded to “What do youbelieve plays an important role during a course”, byremarking that: Professor’s ability to communicate (26.5%) The object of teaching (19%) Professor’s knowledge (16%) Students’ interest for certain course (12.5%) Professor’s teaching experience (10%) Students’ mood (7%) Professor’s mood at a given moment (6%) The duration of the course (3%)227

International Journal of Learning, Volume 11Instructor's ability tocommunicateSubject matter26,5%Instructor's knowledge19%Students' interest16%Instructor's experience12,5%10%7%Students' mood6%3%Intructor's moodDuration of the lessonGraph 2Factors that influence the conduct of the course The students added their own free comments to theprevious question such as: the professor’s love forhis/her subject, the originality in an era dominatedby copies, the professor’s feeling what he/she isteaching, the absence of assessment marks, theprofessor’s scientific background, the groupdynamics, and the relationship between the studentsand the professor.The students were very enthusiastic about thecourse. They considered the teaching method veryunusual for an academic context, their activeparticipation satisfied them and they claimed thatthey had learned many things about the subject.They reported they would modify their traditionalway of thinking about teaching techniques and theirperceptions of preschooler’s capabilities.A Year After the In-Service TrainingCourseIn order to see how students implemented the newteaching perspective we sent questionnaires bypostal mail to the students who attended our coursein 1998-99, 2001-02 and 2002-03.The questionnaires were anonymous and includedopen questions. Some of the questions asked were: Based on your subject area, which course mostinfluenced your personal perceptions? Was there a change in your mode of teachingand dealing with your pupils? Which of the activities that you experienced inmy course did you apply in your class? How did the children respond to theseactivities?228 Was my teaching sufficient in order to meetyour needs in your work?Which other course of the training program hada positive effect on your work?The percentage of questionnaires returned to us(40%) was too small to draw any conclusions or tomake generalizations. The small percentage of ECEteachers that participated in the completion of thepost-questionnaires a year later demonstrated asMoser and Kalton (1971) suggest that a lack ofresponse is a problem, because practice hasrepeatedly proved that, usually, the people whodon’t answer questionnaires are different from thosewho do answer them.As this part of the data collected was not helpful inillustrating our argument we decided to use informalinterviews with 20% of the ECE teachers that wemanaged to meet over the following years.From the interview data, ECE teachers maintainedthat our course about psychomotor activities and theway it was taught influenced them in their personallife, their relations with others and the children andin the improvement of their self-esteem. In theirwork they used the exercises of relaxation forchildren, communication, body expression, activitiesof creativeness and imagination. They all agreed thatthe children accepted the new activities withenthusiasm and they kept asking them to repeatthem.In addition, ECE teachers concluded that very fewcourses from the twenty-five accomplished by otherprofessors, during the two year in-service training,influenced their manner of work or helped themrenew their knowledge. Most ECE teachers

Reforming “Traditional” Teaching Methods in In-Service Training Programs for Early Childhood Teacherscontinued following their old teaching methods andthe two years of in-service training was just viewedas a break from their routine. The courses that drewtheir most positive comments were those thatbroached the subject of communication in theclassroom and those that had a practical application.ConclusionsThe 26 hours of teaching during the semester ledECE teachers to the adoption of new attitudes andperceptions about their personal and professionallife. Most importantly, some teachers startedapproaching their children and teaching differentlyby emphasizing the importance of using the ‘body’as experiential tool in learning through pleasurableactivities. Therefore, they stopped worrying strictlyabout the acquisition of knowledge and insteadshifted their focus toward ‘how’ to teach children.Through the questionnaires and the interviews,ECE teachers pointed out the need for extending theduration of the in-service training program andsuggested that it be accompanied with a directpractical application within the kindergartenclassroom. The personal and professionalimplication of teachers can, consequently, bestrengthened (Eadap, 2003) through a type ofcontinuous school based training and supportteachers to connect the acquired knowledge with thedaily reality in the kindergartens. This in-servicetraining has to take into consideration the students’needs and to involve them actively in the learningprocess. ECE teachers’ comments were focused onan academic style of teaching, which did not givethem the possibility

ISSN 1447-9540 (Online) The International Journal of Learning is a peer-refereed journal published annually. Full papers submitted for publication are refereed by the Associate Editors through an anonymous referee process. Papers presented at the Eleventh International Literacy and Education Research Network Conference on