Transcription

BY FACULTY FOR FACULTYSupporting Nurse PractitionerPreceptor DevelopmentAngela F. Bazzell, MSN, FNP-BC, and Joyce E. Dains, DrPH, FNP-BCABSTRACTIncreases in the number of nurse practitioners (NPs) completing their educational programs create achallenge for universities as well as health care organizations. More clinical preceptors are needed to supportstudents and new professionals transitioning to clinical practice. Although preceptors are critical in theevolution from new NP to competent provider, there is a lack of information available to NP preceptorsrelated to developing effective clinical teaching skills. This comprehensive literature review evaluatescurrent, evidence-based strategies for preceptor development. The findings in the literature showimprovement in clinical reasoning when structured preceptor methods are incorporated into clinicalpractice.Keywords: advanced practice nurse, new nurse practitioner, novice nurse practitioner, nurse practitioner,precepting, preceptor education, preceptor trainingÓ 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.Nurse practitioners (NPs) play a key role inthe delivery of health care, blendingnursing and medicine.1 Approximately20,000 NPs completed their educational programsand transitioned to practice in 2014 to 2015.2Although the transition period for new NPs begins ingraduate programs, much of the expertise and skillsare developed in their first professional position.Preceptors play a key role in the evolution fromnew NP to competent provider. Preceptors mayinfluence the success and role satisfaction of new NPsas well as their intent to stay in their current position.However, in busy clinical environments, patient carealways takes priority over teaching.3The implementation of clinical teaching strategiesfor NP preceptors that identify tools for effectiveteaching in busy clinical environments is needed tomeet the needs of new NP professionals. NP preceptor training could provide the necessary tools tohelp bridge the gap between educational preparationand clinical practice for novice NPs in their firstprofessional role.SCOPE OF THE PROBLEMThe first year of professional practice is a period ofaccelerated growth and development in which NPslearn new skills, increase their knowledge, and evolvewww.npjournal.orginto their new role. A survey of NPs in 2004 foundonly 10% of new professionals felt “very well prepared”4 for practice after completing theireducational program, and 51% felt “they were onlysomewhat or only minimally prepared”4 for practice.Brown and Olshansky5 have identified 4categories of transition that NPs experience duringtheir first year of professional practice: laying thefoundation, launching, meeting the challenge, andbroadening the perspective. Moving from theprotection of an educational environment to the firstprofessional NP position, or launching, is consideredthe most difficult part of the first year of practice.Productivity expectations, feeling like an imposter,dealing with anxiety, and developing organizationaland problem-solving skills are some of the stressorsfaced by new professionals.5One of the factors identified as being essential to thetransition of new NPs is collaborative practice.6Working with providers who can assist in clinicaldecision making and serve as an organizational guide,who have an understanding of the NP role, and who areaware of the challenges of the novice NP may positivelyinfluence role transition. Learners may not knowwhat skills are necessary to master their new role andmay need assistance navigating the transition process.7Preceptorship addresses many of these practice needs.The Journal for Nurse Practitioners - JNPe375

Preceptorship is a 1-to-1 relationship between anovice NP and an experienced provider that offerslearning opportunities and supports the role transitionof the novice.8 The preceptorship model in nursingbegan in the 1970s to help new graduate nursestransition from their educational programs to theirfirst professional nursing jobs.9 Skillful, competentpreceptors are not only subject matter experts but canalso demonstrate clinical judgment and facilitateknowledge acquisition to learners.10Many organizations have programs that supportpreceptor education for registered nurses. The programs are based on research that shows better outcomes for new graduates with preceptor developmentinitiatives.11,12 The National Council of State Boardsof Nursing’s Transition to Practice Study identifiedthat preceptors who are educated for the preceptorrole are associated with effective transition to practiceprograms.13Although the literature supports preceptordevelopment programs to teach preceptors how to beeffective in their role, there are few organizationalresources available for NP preceptors working withNP students or NPs in their first professional role.The 1999 American Association of Nurse Practitioners Preceptor and Faculty Survey found 95% ofpreceptors surveyed would probably or definitelyattend preceptor development programs ifavailable.14As practice-based teaching and accreditation requirements evolve, there is a greater emphasis on therole of the preceptor and preceptor development inall health professions.15 Given the number of newNPs entering the workforce every year, thesefindings validate the need for evidence-based clinicalteaching initiatives for NP preceptors.METHODSA comprehensive review of the literature was conducted to gather peer-reviewed evidence on preceptor development interventions. The electronicdatabases searched included PubMed, Scopus,Cochrane Library, and the Cumulative Index toNursing and Allied Health Literature with thefollowing search terms applied: nurse practitionerpreceptor(s), NP preceptor, preceptor training ANDnursing, advanced practice nurse preceptor, APNe376The Journal for Nurse Practitioners - JNPpreceptor, nurse practitioner role transition, oneminute preceptor AND nurse, novice nurse practitioner, novice advanced practice nurse, new nursepractitioner, transition to practice AND nursepractitioner, one minute preceptor, NP AND preceptorship methods, nurse practitioner AND preceptorship methods, nurse practitioner AND on thejob training AND preceptor, and preceptorshipAND nurse practitioner. The Medical SubjectHeading terms used were preceptorship/organization and administration, preceptorship/methods,attitudes of health personnel, and nurse practitioners/education. A secondary review of referencesfor relevancy and systematic reviews or metaanalyses to identify additional primary sourceswere included.Multiple inclusion and exclusion criteria wereapplied. Research articles published after January 1,2000, and before March 1, 2016, in English andrelated to studies of humans were included. Studiesconducted outside of North America were excludedrelated to differences in education, practice standards,and laws. Research studies addressing registered nursepreceptorship models were excluded related to therole, scope of practice, and learning needs of NPs inclinical practice. Posters, abstracts, and oral abstractswere excluded. Studies focused on preceptor education models for simulation and online educationwere beyond the scope of this review and wereexcluded. A comprehensive search of the literaturefor graduate NP preceptor guidelines was alsoincluded in the review.Two thousand seven hundred eighty-nine fulltext articles were initially identified. After applyingthe inclusion and exclusion criteria, 176 full-textarticles remained, including 12 articles retrieved fromthe reference list review. Many of the articlesexcluded focused on barriers and facilitators for preceptors, preceptee satisfaction, and roles/characteristics of effective preceptors. A review of the remainingarticles found 9 articles met the inclusion andexclusion criteria for preceptor development interventions. No research articles were found thataddressed precepting NPs; therefore, preceptingmodels from medicine and pharmacy were examinedfor this review because the transitions in these disciplines are similar to those experienced by NPs.Volume 13, Issue 8, September 2017

REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCEGuidelinesThere are no published guidelines for preceptorsworking with novice NPs. There are establishedguidelines for clinical preceptors working with NPstudents in the academic setting. The report by theNational Task Force on Quality Nurse PractitionerEducation titled “Criteria for Evaluation of NursePractitioner Programs” states, “Each preceptor musthave educational preparation or extensive clinicalexperience in the clinical or content area in whichhe/she is teaching or providing clinical supervision.”16 Extensive clinical experience in the contentarea is viewed as a substitute for educationalpreparation.The Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education Standards for Accreditation of Baccalaureateand Graduate Nursing Programs states, “Preceptors, when used by the program as an extensionof faculty, are academically and experientiallyqualified for their role in assisting in the achievement of the mission, goals, and expected studentoutcomes.”17 The term experientially qualified17 issubjective, and each academic program determinesthe meaning.Preceptor ModelsPreceptor models identified in the literature for thisreview included a Web-based resource for all healthprofessionals, the One-Minute Preceptor (OMP)learning model, and the SNAPPS 6-step techniquefor case presentations. There were references in theliterature to the Aunt Minnie method and thinkaloud approach; however, no research articles onthese methods were found using the inclusion andexclusion criteria.E-tips. Kassam et al18 developed a Web-basedpreceptor education resource for health careprofessionals. A needs assessment survey of over 500health profession preceptors was conducted andincluded preceptors from 10 different health professions,including nursing.18 The preceptor education modelwas designed to be an interprofessional resource readilyaccessible to preceptors related to the Web-based format.The preceptor model contains 8 modules incorporatingdifferent teaching strategies, including the OMP, andwww.npjournal.orgallows users to view videos, take quizzes, and completeself-reflection exercises.18The OMP. The OMP was developed by theDepartment of Family Medicine at the University ofWashington, Seattle, WA, in 1992. The OMP is a 5-stepmodel of clinical teaching that is applicable across a widerange of clinical settings. The OMP has been used inorienting new nurses and was found to be useful to newand experienced nursing preceptors.19The 5 microskills outlined in the OMP are get acommitment, probe for supporting evidence, teachgeneral rules, reinforce what was done right, andcorrect mistakes.20 The preceptor encourages thelearner to make a commitment to a diagnosis in thefirst step, demonstrating the learner is using clinicalreasoning skills to process the information. After thelearner makes a commitment to a diagnosis, thepreceptor questions the learner on the reasoning forthe diagnosis or probes for supporting evidence. Thisprocess allows reflection for the learner.20 Teachinggeneral rules is an opportunity for the preceptor toaddress mistakes identified in the presentation.Providing positive feedback reinforces what was doneright in the clinical situation. Correcting mistakes isthe last step and allows time for the learner to critiquehis or her performance. According to Neher et al,20mistakes should be framed as not best20 insteadof bad.20SNAPPS. The SNAPPS mnemonic is a precepting model developed for outpatient education;however, it has been used for inpatient preceptingalso. SNAPPS consists of 6 steps: summarize thehistory and physical findings, narrow the differentialto 2 or 3 relevant possibilities, analyze the differentialby comparing and contrasting, probe the preceptorby asking questions about uncertainties, plan management of the patient, and select issues related to thecase and follow up with reading focused on the issuesthat require clarification.21 According to Wolpawet al,21 SNAPPS is a learner-driven preceptingapproach that encourages thinking and reasoning.RESULTSIn reviewing the research articles included in thisreview, 4 themes emerged as measurement variablesin the studies. Synthesis of the intervention results isThe Journal for Nurse Practitioners - JNPe377

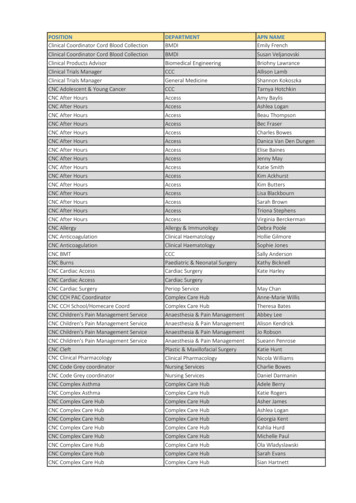

organized by the following themes: student evaluation of models, preceptor evaluation of models,improvements/changes in teaching behavior, andstudent learning outcomes.Student Evaluation of ModelsThree of the studies identified in the literature assessedstudent evaluation of the preceptor model. All of thestudies examined student preference of the OMPpreceptor model. Table 1 illustrates the impact of theOMP on student evaluation of preceptor models.Third- and fourth-year medical students at 2medical schools were surveyed by Teherani et al22 toevaluate the impact of the OMP compared withtraditional precepting methods on teaching points andoverall preference. The authors describe traditionalmethods such as the use of case presentations anddiscussions to verify findings and learning approaches inwhich the preceptor acts as the expert and provideslittle instruction to learners.22 Students viewed 2videotaped precepting encounters, an OMP encounterand a traditional precepting method. Participants used a5-point Likert scale to determine teaching points andoverall effectiveness of the encounter.22 The OMPprecepting model was preferred by the students(mean ¼ 4.52, P ¼ .001) compared with the traditionalmethod (mean ¼ 2.64).22Eckstrom et al23 developed a questionnaire tomeasure the effectiveness of an OMP faculty workshop.Sixty-eight internal medicine preceptors participated,44 in a control group and 24 in the interventiongroup.23 Preceptors completed pre and post selfevaluation surveys of their skills using the OMP.Residents completed anonymous evaluations of thepreceptors every 6 months for 2 years using a scoringsystem from 1 to 4 in which 1 ¼ almost never and4 ¼ most or all of the time. In testing the questionnaire,residents rated preceptors who completed the OMPworkshop as superior in 2 of the 5 microskills of OMP,get a commitment (mean ¼ 3.85, P ¼ .03) and givepositive reinforcement (mean ¼ 3.42, P ¼ .02).23Resident evaluations of the OMP-trained facultyshowed improvement in 4 of the 5 microskills; however, the findings did not reach statistical significance.23The only randomized controlled trial of any of theprecepting methods identified in the literature wascompleted by Furney et al.24 Fifty-seven residents one378The Journal for Nurse Practitioners - JNPinpatient units at 2 institutions participated in thestudy, with 28 participants in the intervention groupand 29 participants in the control group. The intervention group met for 1-hour monthly sessions; theOMP model was discussed, and pocket reminder cardswere provided to reinforce the OMP model. Furneyet al24 surveyed medical students on the residents’teaching skills using a 14-item scale encompassing 5domains of the OMP method: commit, probe, rules,feedback, and overall evaluation. Based on a 5-pointrating scale, the residents in the intervention groupshowed statistically significant improvements (P .05)of at least 1 item in all domains except “teachinggeneral rules” (premean ¼ 3.73, postmean ¼ 4.02;P ¼ .10).24Preceptor Evaluation of ModelsKassam et al,18 Aagaard et al,25 and Furney et al24included preceptor evaluation of the preceptingmodels in their studies. As Table 1 indicates,preceptors reported structured preceptor methodsapplicable and effective to their role.E-tips, an interprofessional Web-based preceptoreducation resource incorporating different teachingstrategies, was developed by Kassam et al.18 Ninetypreceptors from 10 health disciplines evaluated 1 ormore of the 8 modules included in the model.18Using a 5-point scale, 95.5% of the preceptors ratedthe modules as very applicable or extremely applicable, and all respondents stated they would recommend the modules to colleagues.18Traditional preceptor models were comparedwith the OMP by Aagaard et al25 to evaluate thepreceptors’ ability to correctly diagnose and ratestudents and preceptor satisfaction with both models.The authors describe the traditional preceptor modelas one in which preceptors ask basic questions toclarify clinical data and give lectures to students thatdo not promote discussion.25 One hundred sixteenpreceptors at 7 universities viewed 2 cases,pneumothorax and hiatal hernia, with the OMPprecepting model and the traditional preceptormodel. The preceptors rated the students’ abilitiesand their confidence in rating the students andevaluated the effectiveness and efficiency of eachmodel.25 Using a 5-point Likert scale, preceptorsrated the OMP model of precepting as moreVolume 13, Issue 8, September 2017

www.npjournal.orgTable 1. Results by Preceptor ModelsVariablesStudyStudent Evaluation of ModelsPreceptor Evaluation of ModelsImprovements/Changes inTeaching BehaviorStudent Learning OutcomesWeb-based resource95.5% of preceptors rated themodules as very applicable orextremely applicableKassam R, et al. Am JPharm Educ.2012;76(9):168-17660% of preceptors reported themodules increased theirconfidence more thananticipatedSNAPPSNixon J, et al. Acad Med.2014;89(8):1174-1179PICO conformity and qualityof answers correlated withformatting questions forfurther learningWolpaw T, et al. AcadMed. 2012;87(9):1210-1217Preceptors responded touncertainties in the SNAPPSgroup more but not statisticallysignificantWolpaw T, et al. AcadMed. 2009;84(4):517-524SNAPPS students expressedmore uncertainties/clarifiedquestions in casepresentationsThe Journal for Nurse Practitioners - JNPOMPTeherani A, et al. MedTeach. 2007;29:323-327OMP model preferredNo change in teaching pointswith OMP modelEckstrom E, et al. J GenIntern Med.2006;21(5):410-414OMP-trained faculty rated assuperior in 2 out of the 5 OMPdomainsImproved faculty selfassessment of teaching skillswith OMP modelAagaard E, et al. AcadMed. 2004;79(1):42-49Preceptors rated the OMPmodel as more efficient andeffectiveIrby DM, et al. Acad Med.2004;79(1):50-55e379Furney SL, et al. J GenIntern Med.2001;16(9):620-624SNAPPS students were moreconcise and improved inproviding and analyzingdifferential diagnosisPreceptors were more likely tocorrectly diagnose the patientwith the OMP modelTeaching points changed fromgeneric clinical skills to diseasespecific with the OMP modelOMP-trained residents exhibitedimproved teaching skillsOMP ¼ One-Minute Preceptor; PICO ¼ Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome.Preceptors reported increasedoverall teaching effectivenessPreceptors self-reportedimprovement in the use of OMPteaching skills

efficient and effective than the traditional model(P ¼ .00).25Furney et al24 found residents functioning aspreceptors to medical students in the OMPintervention group reported increased overallteaching effectiveness with the OMP teachingmethod (premean ¼ 3.36, postmean ¼ 4.08;P .01). Residents reported a statistically significantimprovement in all of the OMP skills domains,except teaching general rules, which does not have tobe applied in every precepting interaction.24Improvement/Changes in Teaching BehaviorFindings related to improvement or changes inteaching behavior by preceptors were inconsistent inthe literature (Table 1). Kassam et al,18 Wolpawet al,26 Teherani et al,22 Eckstrom et al,23 Aagaardet al,25 Irby et al,27 and Furney et al24 evaluatedimprovement or changes in teaching behaviors withthe precepting models.Wolpaw et al26 compared the uncertainties ordoubts of medical students using the SNAPPStechnique for case presentations (n ¼ 19) with theuncertainties of students using traditional presentations(n ¼ 41). A secondary analysis of data from a 2004 to2005 study was coded for the type of uncertainties andpreceptor responses.26 The coding was of audiotapedpresentations of case presentations by the students.Overall, preceptors responded to uncertainties withinthe SNAPPS group more (82%) than the comparisongroup (79%); however, the increased response rate wasnot statistically significant (P ¼ .74).26The teaching points preceptors listed after viewing2 videotaped encounters of 2 case presentations usingthe OMP and a traditional preceptor model wereexamined by Irby et al.27 The authors describe thetraditional precepting model as one in whichpreceptors ask questions of the learner to diagnose thepatient instead of evaluating the learner’s criticalthinking.27 Preceptors’ teaching points changed fromgeneric clinical skills, such as physical examination,with the traditional preceptor model to diseasespecific teaching points with the OMP model (differential diagnosis, diagnostic tests, and presentationof disease, P .05).27Changes in teaching behaviors using the OMPmethod were evaluated by Teherani et al,27e380The Journal for Nurse Practitioners - JNPEckstrom et al,23 Aagaard et al,25 and Furney et al.24Teherani et al22 found no difference in the teachingpoints requested by medical students between theOMP model and the traditional teaching model.Aagaard et al25 found preceptors who viewedvideotapes of the OMP model in 1 of the 2 tapedcases were more likely to correctly diagnose thepatient (92%) compared with the traditionalprecepting model (76%, P ¼ .02). Eckstrom et al23and Furney et al24 relied on self-reporting by preceptors for the assessment of improved teaching skills.Eckstrom et al23 found faculty self-assessment in theOMP intervention group showed improvement in all5 of the OMP skills/steps, with a statistically significant improvement in 3 of the 5 (P .05). Furneyet al24 found residents assigned to the OMPintervention group self-reported a statistically significant improvement in the use of the OMP teachingskills except “teaching general rules or pearls”24(P .05).Sixty percent of preceptors evaluating the usefulness of E-tips indicated the modules increased theirconfidence more than expected.18 The authors alsofound a positive correlation between the reportedapplicability of E-tips and increases in teaching ability.Student Learning OutcomesThree of the research articles reviewed measuredstudent learning outcomes related to preceptormethods. Nixon et al,28 Wolpaw et al,26 andWolpaw et al29 evaluated student learning outcomeswith the SNAPPS preceptor method. As Table 1indicates, students were more likely to ask questionsabout areas of uncertainty and showed improvedclinical reasoning with structured preceptor methodscompared with traditional teaching methods.PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison,Outcome)-formatted questions were added to the laststep of SNAPPS (select an area of further learning) byNixon et al.28 The content and quality of the PICOquestions were evaluated by the authors. Over a4-year period, 191 medical students submittededucational prescriptions on prescription forms withthe PICO format preprinted on the front and a spacefor students to list their references and level ofevidence on the back.28 The prescriptions werecoded for PICO conformity, the presence of anVolume 13, Issue 8, September 2017

answer on the back of the form, and quality of theanswer. There was a positive correlation between thePICO conformity score and the quality of answers,with quality based on directness, evidence, andmanagement (P .001).28Wolpaw et al29 evaluated whether medicalstudents presenting cases to preceptors using theSNAPPS technique expressed more clinical reasoningthan students not trained in SNAPPS. Sixty-fourstudents were placed into 3 groups: the SNAPPSgroup, the feedback training group, and thecustomary instruction group.29 The studentsaudiotaped case presentations the last week of theirrotations, and the audiotapes were coded forcomparison. Students in the SNAPPS group weremore concise (P .00), taking 14% less time inpresenting and summarizing findings. The SNAPPSgroup also outperformed the other 2 groups inproviding and justifying differential diagnoses(P .000).29The fourth step of SNAPPS is probing, or askingquestions about areas of uncertainty. The expression ofuncertainties using the SNAPPS technique provideslearners an opportunity to question and discuss areasneeding clarification. Wolpaw et al26 evaluatedmedical students’ expression of uncertainties using theSNAPPS technique during case presentations. Theresults found students in the SNAPPS group expresseduncertainty in all case presentations compared with54% of students in the control group (P ¼ .0001).26DISCUSSIONStrengths and LimitationsThe limitations of many of the studies reviewed werethe lack of other health professions included as participants. Only Kassam et al18 included nursing as 1 ofthe 10 specialties evaluating E-tips. There was nodiscussion as to the scope of practice of the nursingprofessionals used to evaluate E-tips. The Institute ofMedicine has recommended academic and healthsystems leaders put resources into interprofessionaleducation to improve the delivery of health care.30NPs are a central part of health care delivery andshould be included in the development andevaluation of precepting methods.Another limitation of the studies was a lack offollow-up over time measuring the impact of thewww.npjournal.orgprecepting methods on patient care. Wolpaw et al26found the SNAPPS group showed a statisticallysignificant improvement in providing and analyzingdifferential diagnosis; however, there was no longterm measurement of patient outcomes in theSNAPPS group. None of the studies used patientoutcomes as a studied variable.The only randomized controlled trial within theliterature reviewed was conducted by Furney et al.24The other research articles evaluated were level III orlevel IV in the hierarchy of evidence, which affect thestrength of the evidence in the findings. Thepublished guidelines outlined for preceptors inacademic settings are based on expert opinion andconsensus reports.CONCLUSIONOverall, the findings of the literature reviewed showimprovement in clinical reasoning when structuredpreceptor methods are incorporated into clinicalpractice. Barker and Pittman31 identified barriers toprecepting, including the effect on productivity,patient expectations of the provider’s attention, andbeing uncomfortable with the teaching role. Webbased preceptor resources, such as E-tips, mayimprove the teaching skills of preceptors withoutimpacting the busy lives of health care professionals.Although not discussed in this review, the relationship between preceptor satisfaction and motivation to stay in the preceptor role must be considered.Preceptor satisfaction is increased when preceptorsfeel their role is supported and goals are defined.32 Asurvey of preceptors working with neonatal nursepractitioner students identified “offering an on-siteworkshop for preceptors”33 and “providingpreceptors with a module related to clinical teachingand precepting strategies”33 as activities that wouldsupport their role the most. The implementation ofpreceptor development programs to support NPpreceptors shows organizational support of theclinical teaching role.The findings of this review have implications forboth nursing research and clinical practice. Theabsence of NP preceptor methods found in theliterature identifies the need for further nursingresearch exploring preceptor methods for workingwith novice providers as well as NP students thatThe Journal for Nurse Practitioners - JNPe381

involve all members of the health care team. Organizations must examine the stress placed on noviceNPs in clinical practice and the effect on patientoutcomes, retention, and job satisfaction. There isalso a need for higher quality research to guide organizations and academia in selecting the best preceptor methods for implementation.References1. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Your partner in health: thenurse practitioner. 2013. brochure.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2016.2. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. NP fact sheet. June 2016. https://www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet. Accessed October 4, 2016.3. Gallagher P, Tweed M, Hanna S, Winter H, Hoare K. Developing the OneMinute Preceptor. Clin Teach. 2012;9:358-362.4. Hart AM, Macnee CL. How well are nurse practitioners prepared for practice:Results of a 2004 questionnaire study. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19(1):35-42.5. Brown MA, Olshansky EF. From limbo to legitimacy: a theoretical model of thetransition to the primary care nurse practitioner role. Nurs Res. 1997;46(1):46-51.6. Billay D, Myrick F, Yonge O. Preceptorship and the nurse practitioner student:navigating the Liminal Space. J Nurs Educ. 2015;54(8):430-437. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20150717-02.7. Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82(3):402-407.8. Goldenberg D. Preceptorship: a one-to-one relationship with a triple “P”rating (preceptor, preceptee, patient). Nurs Forum. 1987;23(1):10-15.9. McClure E, Black L. The role of the clinical preceptor: an integrative literaturereview. J Nurs Educ. 2013;52(6):335-341.10. Davis MS, Sawin KJ, Dunn M. Teaching strategies used by expert nurse practitionerpreceptors: a qualitative study. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 1993;5(1):27-33.11. Goss CR. Systematic review building a preceptor support system. J NursesProf Dev. 2015;31(1):E7-E14.12. Windey M, Lawrence C, Guthrie K, Weeks D, Sullo E, Chapa DW. A systematicreview on interventions supporting preceptor development. J Nurses ProfDev. 2015;31(6):312-323; quiz E19.13. Spector N. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing’s Transition toPractice study: implications for educators. J Nurs Educ. 2015;54(3):119-120.14. Amella EJ, Brown L, Resnick B, McArthur DB. Partners for NP education: the 1999AANP preceptor and faculty survey. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2001;13(11):517-523.15. Weitzel KW, Walters EA, Taylor J. Teaching clinical problem solving: apreceptor’s guide. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(18):1588-1599.16. Nationa

preceptor, nurse practitioner role transition, one minute preceptor AND nurse, novice nurse practi-tioner, novice advanced practice nurse, new nurse . ceptors, when used by the program as an extension of faculty, are academically and experientially qualified for their role in assisting in the achieve-