Transcription

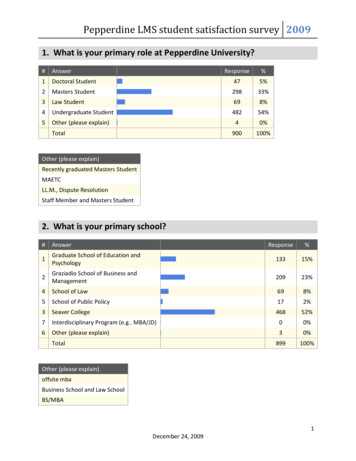

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574Assessing Face to Face and Online Course Deliveryusing Student Learning OutcomesAditya Sharmaasharma@nccu.eduBeverly Bryantbbryant@nccu.eduMarianne Murphymmurphy@nccu.eduSchool of BusinessNorth Carolina Central UniversityDurham, NC 27707ABSTRACTMany factors have led to the increase of online courses and programs. The concern for educators isassuring the quality of education programs. Therefore, online delivery must continually ensure notonly student success but make certain the student outcomes are at least similar. Since online studentsdo not have the opportunity to engage with a dynamic, articulate and knowledgeable instructor, otherengagement methods must safeguard student participation. Just as online courses and programs haveincreased so has technology tools to make work, study and life easier. In this paper, we examine if thetools used to deliver online courses in the Hospitality and Tourism discipline adequately supportstudent learning by comparing the grade distribution of the students between online and face to facedelivery.Keywords: Undergraduate curriculum, Distance Education, Curriculum Delivery tools1 INTRODUCTIONDistance learning is one of the most rapidlygrowing fields of education and it hassubstantially impacted all education deliverysystems (Ghosh, 2012). Few students willgraduate from college without having had somekind of online experience or course delivery. Infact many high school students have completedan online course by graduation. The growth ofonline programs appears to be leveling.According to the Sloan Consortium (2013), theprimary reason institutions create onlinedelivery is to increase student access toeducation programs. They further find that theprimary goal for those institutions mostengaged with online learning is increasingdegree completion.The Sloan Consortium (2013) also identifiesthe barriers institutions cite for online degreedelivery. Two key barriers are the students’discipline and faculty acceptance. The easyadoption of technology tools will play a keyrole in student engagement and facultyacceptance. Online education focuses on theability of students to have open access toeducation and training to make the learners 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 1

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574free from the constraints of time and place,and offering flexible learning opportunities toindividual and groups of learners. For thepurpose of this study, online courses are thosein which 100 percent of the course content isdelivered online. Face- to-Face courses arethose where zero to 10 percent of the contentis delivered online.This paper identifies thetools used to deliver online courses in a degreeprogram and examines and compares themeasured student learning outcomes.2. BACKGROUNDNCCU is primarily a liberal arts school withapproximately 8,300 students. The School ofBusiness offers a bachelor’s of science degreein Hospitality and Tourism (HT).Hospitality and Tourism and OnlineLearning ProgramsThe Bachelor of Science (B.S.) degree inHospitality and Tourism Administration is aprofessional management program. The HTProgram is internationally accredited by theAccreditation Commission for Programs inHospitality Administration (ACPHA) and theAccreditation Council for Business Schools andPrograms (ACBSP). Students majoring inHospitality and Tourism Administration areprepared to become hospitality professionalswho possess the knowledge, managerial skills,and competencies to obtain entry levelmanagement positions and assume leadershiproles in various aspects of this global anddynamic industry. Students obtaining thehospitality and tourism degree earn 22semester hours in the business curriculum. TheProgram maintains a high job placement rateeach academic year. Graduates of the programare employed in lodging, food and beverageservice, convention and visitors bureaus, eventmanagement, resorts, conference centers,cruise lines, and airlines. The program’sMission is to educate and empower a diversepopulation of students for leadership andprofessional roles within the global hospitalityand tourism industry, through academicexcellence, community service, and industrywork experience.The HT area has recently introduced an onlinedegree program which will offer all coursesrequired for the degree via online delivery. Theonline degree in HT mirrors the face to facecurriculum. Faculty members utilize the samecourse syllabi, books, instructional materialswhere possible and measure the same studentlearning outcomes. Faculty members logies to achieve student learningoutcomes. The online degree began offeringcourse work in 2009 and currently enrollsapproximately forty-five students. Studentsenrolled are able to complete all courses onlineexcept the culinary courses. These courses aretaken at the University or at an approvedcommunity college in the student’s hometownor near-by community. National Certificationexaminations are proctored by certifiedproctors.The program was developed to facilitatehospitality industry professional working fulltime and desiring to complete their bachelor’sdegree and those who had begun their degree,and could not finish it due to various reasons.The online degree has attracted a diversepopulation of students who are working fulltime in the industry; those who are changingcareers and traditional students who need theflexibility to take courses while completing aspecial practicum, internship or balancingfamily and school. The program benefits fromthe diversity of students in both the online andface to face. Traditional students are indialogue with non-traditional students anddeveloping in some cases, bonding andmentoring relationships. These relationships asexpressed by students have facilitated a winwin situation as each student in therelationship brings their strengths as they eachwork toward common goals.In order to continually assess the effectivenessof this online degree program, we must bekeenly aware that the education provided inthe online program equals or exceeds the faceto face experience. Among the questions wewanted answered initially were:- Specifically, how do we deliver thesame content?- How do we measure success?- What tools will give us the bestresult?In this paper, we specifically address theeffectiveness of using tools to deliver onlinecontent by comparing the learning outcomes ofthose courses which were taught face to faceas well as online. 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 2

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n25743. LITERATURE REVIEWMeasuring student outcomes in face-to-faceand online course delivery has been examinedin controlled Meta studies (Means, et al 2010)as well as real time data from those teachingboth face-to-face and online courses (Sussmanand Dutter, 2013).Other studies measurestudent satisfaction and rating of instruction.Many studies conclude that student satisfactionand learning are not statistically different whencomparing face to face to online learningexperiences. However, the role of technologyand ability of the instructor to create a similarexperience plays a key role (Finley, et al2004).The significance of online learning in HT highereducation programs is examined in a 2012study by Scairini, Beck and Seaman. Theirstudy examined 5 key questions:-Is online learning strategic?What proportion of HT programs offercourses in either a blended/hybrid orfull online format?Are learning outcomes perceived to becomparable for online versus face-toface?How does online education compare toface to face instruction across specificpedagogical metrics?What is the future of HT onlineenrollment growth?All of these questions are important for HTeducators. What is most significant is thatalmost half of the respondents agreed thatthere is increasing competition for onlinestudents. It is also interesting that nearly 80%of the respondents in the study perceivedonline instruction as superior to face to face.A study by Sciarina, M., Beck, J and Seaman, J(2012) assessed online learning in HT in HigherEducation as a descriptive report, the studycompriseddatafrom231respondentsrepresenting administrators of hospitality andor/ tourism programs from 37 countriesinclusive of the United States. The findingsrevealed that chief academic officers rate thelearning outcomes for online education “asgood or better” than those for face-to faceinstruction, but a consistent and sizableminority consider online to be inferior online tobe inferior. The finding also revealed thathospitality administrators better than 80%considered online instruction superior to faceto face when it comes to scheduling flexibilityfor students as well as the ability of students towork at their own pace.Crawford and Weber (2011) assessed thecurrent climate of hospitality s,studentperformance,studentsatisfaction, and accessibility. The studyreported that Machtmes and Asher (2000)found little difference in distance education andtraditional students on how well they achievedin the courses. Crawford and Weber (2011)further reported differences in the views oftraditional and distance education students asdiscussed by McDowal and Lin (2007) in werereportedtofeelmorecomfortable with a teacher present in theclassroom and that the quality of the teachingwas dependent upon the presence of aninstructor. Distance students tended toexperience barriers that deterred es, social communication challenges(Howard, 2002), and ultimately may cause thestudent to not complete the course.Urtel (2008) assessed academic performancebetween traditional and distance educationcourse formats. The findings revealed thatstudents enrolled in the distance educationcourse did not automatically perform equallyas well, or even better, than as if they were ina face to face course. While age is considered apredictor in enrolling in distance educationcourse versus the face to face, it was not apredictor in subsequent academic success. Thisstudy also revealed that students classified asfreshmenareatriskandearnadisproportionate of DFW’s when taking theclass as distance education than theirfreshmen peers who take the class as a face toface course (65% vs 35%).Hiltz et al. (1999) reported no difference ingrade distribution when comparing face to facewith online approaches to delivery. Waschull(2001) similarly reported no significantdifference in examination performance whenhe compared students’ abilities when studyingonline with their on-campus performance forcorresponding section of the same course.Kenny (2001) in a study of examinationperformance of an online versus face to facesection of the same course, he reported that 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 3

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574with one exception, the online classes “enjoyedno significant advantages or disadvantagescompared to face to face that had all theirexaminations in a standard classroom. He alsostated that that the results did not indicate anysignificant difference in the quality of learningbetween the two delivery methods.Smith and Walters (2012) examined mobilelearning in a small student study as a way toengage HT students. The importance of thisstudy is that the participants saw studentengagement as an advantage for onlinelearning.4. DATA COLLECTIONDutton, J, Dutton, M, and Perry, J (2002)studies how online students differ from lecturestudents, the results of their study revealedthat online students are older and are likely tobe lifelong learning students, are likely to havea job and/or childcare responsibilities, and aremore experienced with computers. Onlinestudents listed conflict with work and flexibilityin studying as being more important thanlecture (face to face) students. Online studentsrated contact with instructor and fellowstudents, motivation from class meetings, andneed to hear a lecture as more important tothem. Online students frequently reportedadvice from university advisors as beingimportant. Dutton et. al. (2002) reportedonline students made significantly higher examgrades than lecture (face to face) students,and the course grades for online students arehigher, but the effect is not significant. Thestudy also revealed that undergraduate status,work status, and computer experience hadlarger effects on online (face to face) studentsthan online students. However the differenceswere not significant.Tools in Online EducationIt is reasonable to assume that most onlineeducators would bristle at the notion thatdelivery of an online course is merely takingface to face content and organizing it in aninternet accessible blackboard. Many in factwould likely agree that delivering a successfulonline course is challenging.The use oftechnology and tools to deliver an onlinecourse is crucial for success.There are many specialized and integratedtools used in web based learning. A wide rangeof tools include commonly used tools such ascoursemanagementsystems,virtualclassrooms and instructor videos and lectures.Finlay et al (2004) attribute use of technologyas well as instruction to student satisfaction.Technology, in particular mobile devices, isubiquitous. Examination of this technology is inits infancy and the relationship between mobiledevices and online learning is not clear.In our effort to compare learning outcomesbetween face-to-face and online deliverymethods, we chose four different courses thatwere delivered both in online and face-to-facesettings over fall 2012 and spring 2013 by thesame instructor in the HT area. These courseswere: HADM 1000- Introduction to Hospitality, A survey of the hotel, restaurant, and tourismindustries; their history, problems, generaloperating procedures, management functions,service excellence, and business protocol;HADM 2000 Introduction to Travel andTourism, a basic understanding of domesticand international trends in travel and tourismto include: the terminology, demographics,historical, economical, social-cultural, andenvironmental trends related to tourismmanagement and sustainable development;HADM 3500- Travel and Tourism Planning, anoverview of integrated tourism planning fororganizations; the development and evaluationof systems approach to comprehensive tourismprojects, and the consideration of advancedconcepts, policies, approaches, and models inregional and national tourism development;and HADM 4200 Hospitality Sales andMarketing, an overview of service marketingas applied to the hospitality industry, includingbut not limited to: unique attributes of consumersandconsumerbehavior, market segmentation principles,target marketing, product planning, promotionplanning, market research, and competitoranalysis.The online and face to face courses weretaught by the same instructor with commoncourse syllabi, content, projects, case studies,examinations etc. End of the semester datawas collected for each course to include:scores for examinations, projects, case studies,grade distribution scores and student ratings ofinstruction. Common instructional technologiesincluded video lectures, power point, You-tubevideo webinar, discussion board, case studies,trend tracking and quizzes and examinations. 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 4

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574Students enrolled in the online degree programin hospitality represent students who aretypically non-traditional, those individuals whoare working in the industry, changing careersor seeking to become entrepreneurs. In fall of2012, the university experienced an increase inthe freshmen class; therefore, the HADM 1000online class enrolled a high number offreshmen students taking the class as anelective.Table 1. Summary of t-test data for meancomparison between online and face-toface methods of course delivery.n number of students in each section* indicates significant difference at P 0.05Mean MeanFace- OnlinetofaceSDSD PFace On- value-to- linefaceHADM10003.16*2.17*1.010.94 0.01n 19n 12HADM20002.52.251.40.97 0.54n 14n 20HADM35003.23.50.940.85 0.38n 15n 14HADM42002.531.870.721.55 0.12n 17n 15All2.86*fourcourses n 652.43*1.061.24 0.04n 61The grade distribution of each section for thesame course was then used to compare theonline vs. face-to-face learning outcomesconsistent with the methodology used bySussman and Dutter (2013). We alsoaggregated the data across all four coursesand compared the grade distribution betweenonline and face-to-face delivery methods.5. DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTSAs a part of our study we captured the data ondifferent interactions between the instructorand students and also among students for bothface-to-face and online courses. A descriptionof the type of interactions and tools andtechnologies used for each of the courses arepresented in Table 2 of the Appendix.The data was analyzed using an independent 2sample t-test to compare the grade distributiondata and difference between means. Summaryof the results of the t-test are presented inTable 1 . Detailed results and box plots of thedata are also presented in the Appendix. As isevident from the results, there is no significantdifference in the grade distributions in 3 of thefour courses that were compared for online andface-to-face instruction delivery. However, incourse HADM 1000 a significant difference wasobserved between the mean grades for the twosections. While the mean GPA for the onlinesection was 2.17, the mean GPA for the faceto-face section was significantly higher at 3.16with a p value of 0.01. This finding suggeststhat online delivery tools need to be improvedfurther and need to be utilized more effectivelyfor this course. Also, overall comparison of allfour courses when taken together revealssignificant difference between the online andface-to-face method of delivery. The face-toface method of content delivery results in asignificantly higher mean GPA of 2.86comparedto mean GPA of 2.43 for onlinemethod of delivery.6. DISCUSSIONThis study compared grade distribution datausing an independent 2 sample t-test todetermine if there were differences betweenonline and face-to-face method of delivery. Theface-to-face method seems to be moreeffective for content delivery as compared toonline delivery in its current form. Newer andperhaps more effective tools need to beinvestigated and utilized by the HT area toengage students more successfully and topromote higher levels of learning.An interesting finding in our analysis is thatsignificant differences in the mean results existbetween online and face to face sections for 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 5

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574the student population in the freshman levelcourse while the differences for higher levelcourses is not significant. Therefore it isimportant to determine how to engage theyounger student. While it can be argued thatthe students in online vs. face to face selfselect the delivery modes and hence thedifferences exist between the two groups, ourresults and analysis shows otherwise. As hasbeen mentioned in the literature survey sectionDutton et al. (2002) and the data collectionsection of this study, there is no significantdifference between our online and face to facestudent populations in terms of their admissioncriteria and their potential in meeting theireducational goals. If anything our onlinestudent population is expected to be moreresponsible as it consists of more nontraditional students.Future research will investigate the use ofmobile tools and interactive activities. Inparticular more real time discussion in chatroom, short videos and same time differentplace techniques will be investigated.Asynchronous Learning Networks, 4, jaln-vol2issue 2.htm.Kinney, N. (2001) A guide to design andtesting in online psychology courses,Psychology Learning and Teaching , 1, 1,16-20Machtmes, K., & Asher, J. W. (2000). A meta‐analysis of the effectiveness of telecoursesin distance education. American Journal ofDistance Education,14(1), 27-46.Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., &Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidencebased practices in online learning: A metaanalysis and review of online learningstudies. Technical Report. U.S. Departmentof Education, Washington, D.C.7. REFERENCESMcDowall, S., & Lin, L. C. (2007). AComparison of Students' Attitudes towardTwo Teaching Methods: Traditional versusDistance Learning. Journal of Hospitality &Tourism Education, 19(1), 20-26.Crawford, A. and Weber, M. (2011) DistanceEducation in Hospitality Management:What is the current Climate?. TheConsortium Journal Volume 16, Issue 2,15-24.Sciarini, M., Beck, J., and Seaman, J. (2012).Online Learning in Hospitality and TourismHigher Education Worldwide: A descriptivereport as of January 2012. Journal ofHospitality and Tourism Education 24(2/3),41-44.Dutton, J, Dutton, M, and Perry, J, (2002) Howdo online students differ from lecturestudents? JALN volume 6, Issue 1, 1-19.Finlay, W., Desmet, C., & Evans, L. (2004). Is itthe Technology or the Teacher? AComparison of Online and TraditionalEnglish Composition Classes. Journal ofEducational Computing Research 31(2),163-180.Ghosh, S. (2012). Open and Distance Learning(ODL) Education System-Past, Present AndFuture–ASystematicStudyofanAlternative Education System. Journal ofGlobal Research in Computer Science,3(4), 53-57.Hiltz, R, Coppola, N, Rotter, N, Turoff, M andBenbunan-Fich, R (1999) Measuring theimportance of collaborative learning for theeffectiveness of ALN: a multi-measure,multi-methodapproach,JournalofSmith, S., and Walters, A (2012). MobileLearning: Engaging today’s hospitalitystudents. Journal of Hospitality andTourism Education 24(2/3), 45-49.Sussman, S., and Dutter, L. (2013). ComparingStudent Learning Outcomes in Fact-To-Faceand Online Course Delivery. Online Journalof Distance Learning Administration m Online Nation: Five Years ofGrowth in Online Learning. Retrieved ations/survey/online nationUrtel, Mark G. (2008) , Assessing academicperformance between traditional anddistanceeducationcourseformats. 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 6

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574Educational Technology and Society, 11(1), 322-330.and evaluation, Teaching of Psychology, 28,2,143-7.Waschull, SB (2001), The online delivery ofpsychology courses: attrition, performance 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 7

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574APPENDIXTable 2. Description of Interactions and Tools used in Face- to-Face and Online CourseDeliveryInteractions/ Tools &TechnologiesInteractions/ Tools & TechnologiesFace-to FaceOnlineHADM1000PowerPoint Presentations, Quizzes,Exams, Face-to-face consultations,video presentations, class lecturesPowerPoint Presentations, Quizzes, Exams, Oneon-one phone consultations, video lectures,video consultations (Skype, Any meeting)HADM2000PowerPoint Presentations, Quizzes,Exams, Face-to-face consultations,Career Advisement, videopresentations, class lecturesPowerPoint Presentations, Quizzes, Exams, Oneon-one phone consultations, You TubePresentations, TED Talks, Video webinarrecording, Trend of the week postingsHADM3500PowerPoint Presentations, Quizzes,Exams, Face-to-face consultations,video presentations, class lecturesPowerPoint Presentations, Quizzes, Exams, Oneon-one phone consultations, video lectures,video consultations (Skype, any meeting)HADM4200PowerPoint Presentations, Quizzes,Exams, Face-to-face consultations,Career Advisement, videopresentations, class lectures,Discussion Board Interactions for casestudies, Trend Tracking activities,Anymeeting webinar, Email interactionPowerPoint Presentations, Case Studies, Quizzes,Exams, One-on-one phone consultations, VideoLectures , Discussion Board Interactions for casestudies, Trend Tracking activities, Anymeetingwebinar, Email interactionCoursesNote: Students were required to use technologies such as Prezi, Powerpoint, VOPP and VideoPresentations in delivering the assigned work for all courses. 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 8

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574Box & Whisker Plot: .61.4FFOLGroupingMeanMean SEMean 1.96*SET-tests; Grouping: Grouping (assessmentcompare)Group 1: FFGroup 2: OLMeanMeant-value dfpValid N Valid N Std.Dev. Std.Dev. F-ratiopVariableFFOLFFOLFFOLVariances VariancesHADM1000 3.157895 2.166667 2.726394 29 0.0107481912 1.014515 0.937437 1.171204 0.809580 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 9

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 10

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574Box & Whisker Plot: GroupingMeanMean SEMean 1.96*SET-tests; Grouping: Grouping (assessmentcompare)Group 1: FFGroup 2: OLMeanMeant-value dfpValid N Valid N Std.Dev. Std.Dev. F-ratiopVariableFFOLFFOLFFOLVariances VariancesHADM2000 2.500000 2.250000 0.617108 32 0.5415301420 1.400549 0.966546 2.099675 0.137894 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 11

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 12

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574Box & Whisker Plot: ngMeanMean SEMean 1.96*SET-tests; Grouping: Grouping (assessmentcompare)Group 1: FFGroup 2: OLMeanMeant-value dfpValid N Valid N Std.Dev. Std.Dev. F-ratiopVariableFFOLFFOLFFOLVariances VariancesHADM3500 3.200000 3.500000 -0.896379 27 0.3779731514 0.941124 0.854850 1.212030 0.734539 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 13

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574Box & Whisker Plot: FOLGroupingMeanMean SEMean 1.96*SET-tests; Grouping: Grouping (assessmentcompare)Group 1: FFGroup 2: OLMeanMeant-value dfpValid N Valid N Std.Dev. Std.Dev.F-ratiopVariableFFOLFFOLFFOLVariances VariancesHADM4200 2.529412 1.866667 1.581757 30 0.1241921715 0.717430 1.552264 4.681361 0.004217 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 14

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 15

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574Box & Whisker Plot: ALL Courses3.23.0ALL Courses2.82.62.42.22.0FFOLGroupingMeanMean SEMean 1.96*SET-tests; Grouping: Grouping (assessmentcompare)Group 1: FFGroup 2: OLMeanMeant-value dfpValid N Valid N Std.Dev. Std.Dev.F-ratiopFFOLFFOLFFOLVariances VariancesVariableALL Courses 2.861538 2.426230 2.119020 124 0.0360836561 1.058846 1.244441 1.381286 0.204752 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 16

2013 Proceedings of the Information Systems Educators ConferenceSan Antonio, Texas, USAISSN: 2167-1435v30 n2574 2013 EDSIG (Education Special Interest Group of the AITP)www.aitp-edsig.orgPage 17

delivered online. Face- to-Face courses are those where zero to 10 percent of the content is delivered online. This paper identifies the tools used to deliver online courses in a degree program and examines and compares the measured student learning outcomes. 2. BACKGROUND NCCU is primarily a liberal arts school with