Transcription

broadcasterthe magazine of Concordia University, Nebraskasummer 2013 volume 90 no.2

from thepresident’s deskIt is nearly impossible to grow up in Iowa and live in theHeartland of the USA for most of one’s life and notappreciate the power God has placed in a seed. After morethan five decades of life, I continue to marvel at how Godcan use a dry, shriveled seed to bring a beautiful plant toflower and flourish. During my childhood, we would takerides in the country to “check on the crops.” Today, as Laurieand I travel she frequently reminds me to keep my eyes onthe road instead of the rows and rows of crops growing withabundance in the fields of midwestern farms.However, seeds—corn, soybean, wheat, grass, flower, milo—aren’t the only seeds growing around and at ConcordiaUniversity, Nebraska. There is a much more important seedGod is growing in the hearts and lives of students, staff andfaculty: the Seed of the Word of God. In Luke 8, Jesus tellsthe parable of the farmer scattering seed and, in verse 11, asJesus explains the parable to his disciples he says: “the seedis God’s word.”In this issue of the Broadcaster multiple stories are told aboutConcordia students and alumni who, by God’s grace throughthe gift of faith, have the Seed of God’s Word growing intheir hearts and lives. As they learn, serve and lead theseindividuals are proclaiming and practicing the love of Godin their vocations, communities, places of employment,congregations and right here on campus.As an Iowa farm boy I know the hard work farmers investto produce a crop. I also know as a child of God, that noseed reaches the harvest without the creating and sustainingpower of our Creator. In the same way, much hard work,prayer and effort goes into equipping students at ConcordiaUniversity, Nebraska. Yet, without the power of the HolySpirit and the financial gifts and prayers you provide, ourstudents would not reach the potential and plan God intendsfor them. Thank you for helping us sow the Seed of God’sWord and celebrate its abundant blessings in God’s world.The university seal, depicting the parable and containing verse11, is imprinted on every diploma received by our graduates.Brian L. FriedrichPresident2photo: Dan Oetting

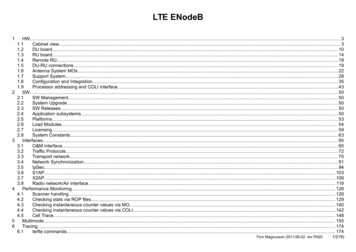

Broadcaster StaffEditorsAndrew Swenson ’08Jenny HammondContributing WritersAdam Hengeveld ’09Jacob KnabelContributing DesignersAndrew Swenson ’08Michael Scheer ’14contentsrise with the raptorsUniversity AdministrationA service learning project helped EthanHutton discover a passion for ecology and anew direction for his future.President & CEORev. Dr. Brian L. FriedrichProvostDr. Jenny Mueller-Roebkepage 4Executive Vice President, CFO & COODavid Kummmultiply the futureVice President for Enrollment Management,Student Life & AthleticsScott SeeversLesa Covington Clark’s success atteaching math doesn’t just equal highertest scores for the students in herclassroom, it equates to providing greatersocial justice in their lives.Vice President for Institutional AdvancementRev. Richard MaddoxBoard of RegentsDr. Dennis Brink, Lincoln, Neb.Mr. Robert Cooksey, Kirkwood, Mo.Dr. Lesa Covington Clarkson, Woodbury, Minn.Rev. Dr. Brian Friedrich, Seward, Neb.Rev. Eugene Gierke, Seward, Neb.Rev. Keith Grimm, Omaha, Neb.Mr. Barry D. Holst, Kansas City, Mo.Mr. James Knoepfel, Fremont, Neb.Mr. John Kuddes, Leawood, Kan.Mr. Lyle Middendorf, Lincoln, Neb.Mr. Timothy Moll, Seward, Neb.Mrs. Bonnie O’Neill Meyer, Palatine, Ill.Mr. Paul Schudel, Lincoln, Neb.Mr. Timothy Schwan, Appleton, Wis.Rev. Dr. Russell Sommerfeld, Seward, Neb.Dr. Andrew Stadler, Columbus, Neb.Mr. Max Wake, Seward, Neb.Mrs. Jill Wild, Seward, Neb.page 8planting rail cars& wheat fieldsAs the executive director of Seward CountyEconomic Development, Jonathan Jankaims to keep Seward growing and thrivingfor years to come.page 12Concordia Scene16Athletics30Alumni News52Alumnotes59General Informationcune.edu 800 535 5494Athleticsathletics@cune.eduAlumni Relationsalumni@cune.eduBookstorecunebooks.comon the coverInstitutional Advancementdevelopment@cune.eduCareer servicescareerservices@cune.eduGraduate Studiesgradadmiss@cune.eduCenter for Liturgical Artliturgicalart@cune.eduJesus once compared the kingdom of heaven to a mustard seed (Matthew 13:31-32)—although theseed starts out small, it grows into large plant. So too at Concordia, we are part of a generation ofsowers, planting the seeds of service and leadership to reap rewards later.Undergraduate Admission& Campus Visitsadmiss@cune.eduMarketing Officemarketing@cune.eduThe Broadcaster is published by Concordia University,Nebraska and distributed to 50,000 alumni, faculty, staff,pastors, businesses, parents and friends of the university inall 50 states and over 15 foreign countries. 2013 Concordia University, Nebraska3

4

Ethan Hutton, a Concordia senior from Norton Shores, Mich., pulls on a thick leatherglove and bends slowly behind a coveredcage. As he straightens, a brilliantly white owlemerges from behind the cage, perched calmly onHutton’s fist.Hutton stands tall with clear confidence, but the50 or so elementary kids in the room don’t notice.They’re all staring at the bird.There’s something invigorating about being just feetaway from a creature you normally only see in photos. There’s also something special about being inthe presence of an owl—its stately gaze and deepset eyes make you feel like its seeing everything.“I’d like you to meet Nimbus,” Hutton says, “And before you ask, no, he’s not the owl from Harry Potter.”photo: A. Swenson5

photo: A. SwensonHutton, like many Concordia students, came to college with a clear idea ofthe career path he wanted to pursue, only to discover that the profession hehad always dreamed of just wasn’t right for him.“Since I was in fifth grade, I wanted to be a pediatric neurosurgeon,” Hutton recounts. “I had a back surgery when I was11 that had a big influence in my life. I figured I would do thesame thing for people. I came to Concordia thinking I wasgoing to go to med school.”Then Hutton started his sophomore year.Although he was succeeding in his premed courses, his passion for the subjectwaned. He wasn’t sure what to do, so heturned to two trusted professors.During his struggle, Hutton added a second major in theology. Although Prof. Groth did suggest Hutton might make agood pastor, he also encouraged Hutton tostick with biology, saying that “the churchchurch needs needs more biologists and the biologybiologists and field needs more theologians.”“.themorethe biology field needsmore theologians.”“Professor [of biology] Gubanyi and professor [of theology] Groth really helpedme in my struggle of not knowing whatto do in life. They never told me what I should do—whichwas frustrating,” he said with a laugh. “I wanted an answer.”This approach, in fact, is very deliberate on the professor’spart. “Students will come to my office and say, ’What do Ido?’” said Dr. Gubanyi.6“I can’t tell them—the student has to make that decision.What I’ll try to do as a professor is tell them the things theycan do to answer that question for themselves.”Still unsure of his path, Hutton signed upfor a service learning course he needed totake in order to fulfill his general education requirements. Sticking with one ofhis majors, he chose Biology 380 – Biology Service Learningwith Dr. Gubanyi in which he learned about the anatomyand physiology and rehabilitation of raptors like owls, eagles,hawks and falcons.And something changed.

“Through that course I realized that my passion wasn’t inmedicine, but that it’s in the Lord’s creation. It’s in ecology.It’s in conservation biology. It’s in preserving biodiversity.”As part of any service learning course, one of the principlerequirements is completing a number of service hours thatrelate to the subject of study. Hutton chose to complete his atRaptor Recovery Nebraska—an organization that providescare and support for injured and orphaned raptors in preparation for release.Despite finally finding his passion, Hutton still had to facethe challenge of getting an internship. Hutton remembers,“when I called to set something up, the director of Raptor Recovery sounded very skeptical. I thought they weren’t goingto want me to be an intern. ”Hutton was partially right. Betsy Finch, Raptor Recovery’sdirector, is skeptical of most people who want to volunteer, but for good reason. “Many people think volunteeringout here means they just get to play with birds,” she said.“What they don’t realize is that these birds are dangerous. They would just as soon rip your lip off as look at you.“It takes a certain kind of person tolearn how to handle them. It’s not foreverybody. Our obligation is to thebirds. It’s our responsibility to protectthem.”Still, Hutton asked for a chance toprove himself. So Finch agreed to allow him to come and do a few dirtyjobs—like cleaning carpets.eyes. I was fascinated.“That was the first moment that I realized how much I wanted to work with animals, and in particular raptors.”Hutton has since gained even more responsibility. In addition to frequently presenting at educational events, he haseven overseen the Raptor Recovery facility when Finch hasbeen away.Finch is delighted to have worked with Hutton. “Throughhis hard work and diligence he earned our trust. Now we’reat a point where we feel like he’s family.”What’s been the most exciting for Hutton, however, is theconnection he’s made between his theology and biology majors.“Christians have the biggest reason to take care of creation.Scientists are doing it to preserve biodiversity, but Christianshave a command from God to govern His creation and totake care of it and preserve it.“That’s where I see raptor recovery. Nearly all the birds theyget in are results from humans, whetherthey’re hit by a car or shot or things ofI still can remember the those sorts. It’s a way of taking care offirst bird they let me God’s creation.”handle, a Great HornedOwl. I remember carrying it from one cage tothe next and looking atits eyes. I was fascinated.And Raptor Recovery isn’t about savingjust a few birds. Over the last 37 years,Raptor Recovery Nebraska has treatedover 11,000 raptors, over half of whichhave been able to be re-released into thewild.When injured birds are first admittedto Raptor Recovery, they are placed insmall crates in an intensive care unit. Each crate’s floor is fitted with a small carpet square that gets soiled in short order.Hutton’s job was to take out each carpet, scrape it down andrinse it off.“Raptors are crucial for the environment,”Hutton says, “and I appreciate God’s design for this. They eat rodents and insects and things that carry disease. One eastern screech owl will eat about 900 miceper year. That’s small compared to a great horned owl or agolden eagle.“It took me a couple of times to learn it,” Hutton laughs, “butyou keep your mouth closed when you scrape.”“Raptors are needed to keep diseases down in the entire U.S.”Among other dirty jobs Hutton had to clean out water bowlswhich were often covered with algae and had rat remains. “Itnever smells good,” he said.While some people might have given up when faced withsuch a mucky task list, Hutton drove the 50 miles fromSeward to Elmwood two to three times every week to cleanout cages without pay.Hutton now sees his calling to continue the work of ecology and conservation biology as a steward of God’s creation.Now that he has his bachelor’s degree, he’s planning to continue ecology study in graduate school.But for now, that means stewarding the environment onedirty carpet square, one educational event, one injured birdat a time.Eventually, Finch invited Hutton to help handle the birds—an experience he remembers well. “I still can remember thefirst bird they let me handle, a Great Horned Owl. I remember carrying it from one cage to the next and looking at its7

8

Lesa Covington Clarkson, a 1980 graduate of Concordia, current Concordia regentand assistant professor at the University of Minnesota, believes that the path to socialjustice is inseparable from the student of math.She has the research to back it up, but even as the list of her publications and awardsgrows, she remains focused on what’s really important, “These are people’s lives. Theseare the lives of children. You just don’t get a second chance.”photo: A. Swenson9

One morning Lesa Covington Clarkson picked up the local newspaper andsaw that the results from Minnesota’s basic skills tests had been released. As amath education Ph.D. candidate she turned immediately to the math section,only to find something deeply troubling.“Seventy-five percent of the white kids were proficient inmath. Twenty-five percent of the black kids were proficient.That’s a problem,” she said, adding as any good math teacherwould, “you don’t have to do a statistical test to say that issignificantly different.”This troubled Covington Clarkson, not only as an educatorbut as a parent. “I raised three children who have brown skin.I needed to know —I needed to prove—that a correlation between skin color and achievement in math just doesn’t exist.”Covington Clarkson herself is somewhat of an anomaly. Sheis the only African-American to have earned a Ph.D. inmathematics education from the University of Minnesota.Her pride of accomplishment is mixed with concern. “Therehas to be a reason why people of color, of underrepresented populations are not succeeding in math,” she said. “Whatthat means to me is that I have to back-map to the classroomto find out what’s happening.”In Covington Clarkson’s experience at any grade level, themore advanced math classes are, the less diverse the studentsare; the more remedial, the more diverse the students.“That’s disturbing,” she explained, “because the number ofjobs that people will have access to is dependent on theirmath and science abilities.“As the population becomes more and more diverse, there aregoing to be fewer and fewer people who are actually preparedto take adva

Ethan Hutton, a Concordia senior from Nor-ton Shores, Mich., pulls on a thick leather glove and bends slowly behind a covered cage. As he straightens, a brilliantly white owl emerges from behind the cage, perched calmly on Hutton’s fist. Hutton stands tall with clear confidence, but the 50 or so elementary kids in the room don’t notice.