Transcription

Taliban historyof war and peacein AfghanistanFelix KuehnFelix Kuehn is the co-editor of My Life with the Taliban, thepoetry written by Taliban members; and co-editor of The Talibanautobiography of the former Taliban envoy to Pakistan, MullahReader (Hurst, forthcoming). Kuehn holds a degree from the SchoolAbdul Salam Zaeef (Hurst, 2010); co-author of An enemy we created:of Oriental and African Studies in London and will defend his PhDThe myth of the Taliban/Al-Qaeda merger, 1970–2010 (Hurst, 2012);thesis submitted to King’s College London Department of Warco-editor of Poetry of the Taliban (Hurst 2012), a volume ofStudies later in 2018.ABSTRACTWhat does conflict in Afghanistan look like to theTaliban and how can greater knowledge of how themovement functions inform better peace policy?Misconceptions of the Taliban have complicatedefforts to end the war in Afghanistan. A key exampleis the extent to which the movement represents thegrievances of a significant section of Afghan society.The Taliban are not unified. From inception the movementhas included distinct groups with different views on nationaland international policy. But the core message of thecentral leadership has resonated widely: Afghanistan needsto return to law and order, and the Taliban are here todispense security and justice based on Islam. The Taliban’smilitary conquest of Afghanistan has reflected their corebelief that holding a monopoly of power is a precondition forthe formation of a viable Afghan state.The movement sees itself as inclusive – not alignedwith any group nor based on ethnicity or a politicalprogramme but following Islam alone. The Taliban’sresurgence in the 2000s mirrored their initial rise topower, facilitated by widespread public discontentwith the new government. They see themselves andthe US as the real stakeholders in the conflict and solikewise in any reconciliation process.The Taliban are perhaps less exceptional in Afghanistanthan many people would prefer to believe, as theyexpress a much broader discontent that is anchored inlocal conflict. The Taliban’s narrative of the conflict inAfghanistan is not an alternative history, but rather amissing piece of the larger puzzle of how to administerthe country peacefully.Incremental peace in Afghanistan // 35

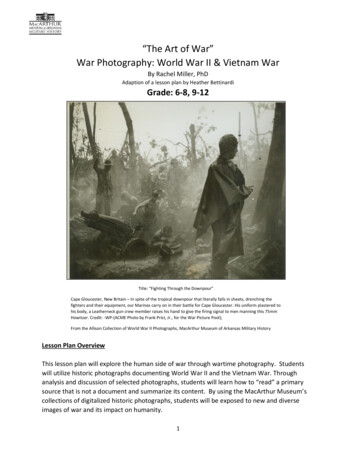

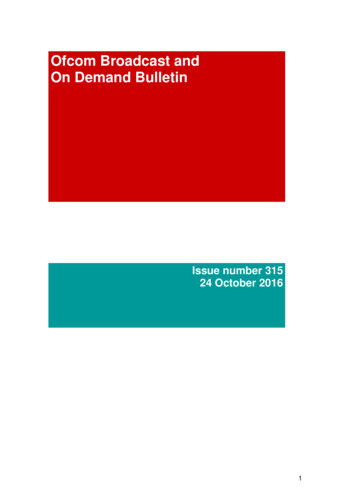

Former Taliban fighters line up to hand over their rifles to the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan during a reintegration ceremonyat the provincial governor’s compound May 28, 2012 in Ghor, Afghanistan. DOD Photo / Alamy Stock PhotoThe history of the Taliban remains a phenomenon.Not because it is impossible to explain who they are,why they started or why they were so successful.But because politically motivated alternative narrativeshave proven even more durable than the group itself.There are fundamental misconceptions about what theTaliban were and are, and what they were not and are not,which complicate efforts to end the war. While the Talibanleadership is made up of distinct groups and individuals,the movement from in the 1990s through to today remainsan expression of the sentiment of a significant section ofAfghan society. There are many Taliban versions of thepast. For all the distortion and propaganda these contain,much is to be learnt from the Taliban’s understandingof the Afghan crisis.BeginningsThe Religion of Allah is being stepped on, the peopleare openly displaying evil, the People of [Islam] arehiding their Religion, and the evil ones have takencontrol of the whole area; they steal the people’smoney, they attack their honour on the main street,they kill people and put them against the rocks onthe side of the road, and the cars pass by and see thedead body on the side of the road, and no one daresto bury him [ ].Mullah Omar was addressing the first group of religiousstudents in Panjwayi, describing the situation allaround Kandahar in 1994. After the Afghan mujahidinhad successfully driven out the Soviet forces and thegovernment it had left behind in Kabul, Afghanistandescended into war with itself. Mullah Omar – and36 // Accord // ISSUE 27many others – believed that ‘control was in the hands ofthe corrupt and wicked ones’. For much of the Talibanleadership, the men who would follow Mullah Omar, itwas clear that the civil war had been fuelled by outsideinterference, and that the victory of the jihad had beenspoiled by the selfishness of the mujahidin commanderswho were fighting each other in a struggle for power.But the crisis was more than just a few mujahidincommanders and their foreign supporters; the Talibansaw that the Afghan people had lost their way. They hadbeen hiding their religion, which had allowed the chaosand anarchy to take hold as the loosely affiliated networksof local mujahidin disintegrated and the commandersturned on communities. A Taliban op-ed from mid-1995,some seven months after the movement had started, isillustrative: ‘We all witnessed what happened when therewas no shari’a law in the country. The last few years area good example of the disaster a society faces without astrict code or law.’There are differing views on matters of national andinternational policy within the Taliban, and to think ofthe movement as one group is misleading. Even in theirearliest incarnation there were distinct Taliban groups.Nevertheless, the core Taliban message resonated widely– that Afghanistan needed to return to law and order andthat they had come to provide security and justice on thebasis of Islam.For the Taliban, their early success was not built on theirsuperior military might but was an expression of thewidespread discontent and desperation about the steadilydeteriorating situation. As Mullah Omar explained in

1995: ‘We asked the religious scholars for their adviceand received a shari’a-based decree from them. Inthe light of this decree from our religious scholars, westarted our armed resistance to the corrupt regime inKabul. We started this movement for the protection of thefaith and the implementation of the shari’a law and thesafeguarding of our sovereignty.’After their momentous success in taking Kandaharprovince, the Taliban’s growing momentum soon convincedthem to turn their sights nationwide. While they onlyestablished an official government after the fall of Kabulin 1996, by spring 1995 they had already transformedthemselves from a loosely structured network of separategroups. They organised as the mujahidin groups of the1980s had, developing their capabilities to raise finance,fight and negotiate. Within four months of starting theyhad not only managed to expand their reach to within a fewkilometres of Kabul, but had also established committeesand departments that, however poorly they performedin practice, were meant to fulfil government functionsof international diplomacy, healthcare and economicdevelopment – alongside the movement’s core goals ofproviding security and justice.National conquest: ‘peace, justice,security and Islam’The Taliban’s primary objectives were informed by whatthey considered to be the precondition for the formationof a viable Afghan state, ie holding the monopoly of power.While they expanded their territory and ranks mostlythrough incorporation and negotiation, the Taliban’sunderstanding was that as long as the option to fightexisted then there would be fighting, or Afghanistan asa whole would fracture. As Mullah Ghaus, the Taliban’sfirst acting minister of foreign affairs, would explain, ‘theTaliban are facing opponents [ ] who want to increasetheir military advantage through war. There are too manyarms in Afghanistan; the war would not end until they weredisarmed. [The] Taliban would continue to fight until allAfghans were disarmed and the country secure.’To much of the outside world, this seemed to be little morethan the Taliban requiring all other Afghan factions to laydown arms and surrender. The Taliban’s point of view,however, was markedly different. In contrast to how theywere perceived externally as well as by some other Afghanfactions, the Taliban did not consider themselves to beparty to the civil war of the early 1990s. They had come toend the civil war and so were a group apart. This mission,according to the Taliban, was not about excluding people.Quite the opposite. As they often claimed, they were notaligned with any group, were not based on ethnicity or apolitical programme, but were following Islam alone.Islam would provide the framework on which others shouldbe operating. From this perspective, the central goal of anIslamic government based on shari’a could not seriouslybe disputed since this had been what all Afghan mujahidinhad fought and died for in the jihad against Soviet forces.As Mullah Omar stated in the summer of 1995, which musthave been confusing to the outside world at the time: ‘theIslamic movement of the Taliban was trying its best andmaking all sorts of possible efforts to prevent any potentialconflict in the country.’ Much of what the Taliban actuallydid, however, was reactive. They were making things upas they went. The overall goals they propagated – peace,justice, security and Islam – resonated widely. But theywere also loosely defined and the details were oftendiscussed as issues arose.In September 1996, the Taliban took Kabul. Mullah Omarannounced that ‘After this, a pure Islamic governmentwill rule over Afghanistan.’ The Taliban would go on toform a government – which meant for the most partreopening previous ministries and encouraging peopleto return to their workplace. But at the time of MullahOmar’s statement, the Taliban did not rule Afghanistan.The ministers that were appointed then were ‘acting’:theirs was a transitional government, and Afghanistan’sfuture was to be decided once the war had ended.Meanwhile, the Taliban would focus on their main missionof preventing a return to chaos and harvesting the fruitsof the hard-won jihad.Kabul, long the motor of innovation and modernity inAfghanistan, seemed for much of the Taliban to be theepicentre of what had gone wrong. After all, it had been inthe capital that unhealthy ideologies such as Communismand Muslim-Brotherhood-inspired Islamism had seepedinto society. To this end the Amr bil Ma’rouf, better knownas the Ministry for Vice and Virtue, was created soonafter Kabul fell – having previously been established onlyas a department. In line with some of the core tenets ofthe Hanafi school of jurisprudence, much of the Talibanleadership believed that shari’a was meant to create asociety that allowed people to be good. The mixture ofrural village culture and religious education that formedthe socio-educational background of many senior Talibanleaders had created a highly ritualistic and outwardoriented religious understanding: if something couldcorrupt people, it should not be allowed.Between 1996 and the end of their Emirate in early 2002,the Taliban continued to try and redress the core issuesthey considered to be the reason for the Afghan crisis. Whilethey did engage in various negotiation tracks to try to endthe war with the opposition, none yielded any results. TheTaliban saw the opposition as untrustworthy and so the warIncremental peace in Afghanistan // 37

continued, as opposition forces either consolidated aroundAhmed Shah Massoud or fled the country. The problemsthe Taliban faced while trying to institute a functioninggovernment and state were the same that many aspiringadministrations had encountered before: establishingboth authority over a fiercely independent population and amonopoly of violence within the country’s sovereign borders.It was arguably their understanding of the underlyingcauses of the Afghan crisis and the solutions to thesethat separated them from previous rulers. Rather thanorientating themselves towards Western countriespromoting modernisation or following foreign ideologies,the Taliban brought with them a mixture of rural Pashtuncustoms and religious education that informed what theythought needed to be changed, mostly in urban centres.A closer look at how they ruled in much of Afghanistanshowed that in practical matters of governance, inparticular the rural hinterlands, more often than not theyrelied on similar arrangements to those that had allowedother governments before them to rule – at least nominally.Fall from power and insurgencyThe Taliban’s international relations soon came to bedominated by links with Osama bin Laden and other foreignnationals accused of involvement in terrorism. The list ofconcerns of the international community, and particularlyof the US, had been growing since the Taliban emergedin Kandahar: from opium production, to the treatment ofthe population and especially women and girls, and thento bin Laden and terrorists. The US and Saudi Arabia hadbeen first to protest about bin Laden, but his presencein Afghanistan soon started to dominate much of theTaliban’s interaction with the world.From the Taliban’s perspective there seemed littledifference between meeting a US diplomat or arepresentative of the UN. The US was, in their words,‘finding [ ] excuses against the Emirate and the top one isthe presence of Arab mujahid, Osama bin Laden. [ ] even ifOsama got out of Afghanistan, they would still not formallyrecognise the Islamic Emirate and neither would Osama’sdeparture put an end to their pretexts.’ Diplomatic effortsbore little fruit. Bin Laden continued to threaten the USand other nations and was held responsible for the 1998bombings of two US embassies in East Africa.The US retaliated with cruise missile strikes and laterimposed sanctions on the Taliban aimed at forcing them tohand over Bin Laden. UN sanctions soon followed, which,to the Taliban, only confirmed the UN as little more thananother US tool. To this day, much of the Taliban leadershipnot only maintains strong doubts as to bin Laden’sinvolvement in the 1998 bombings but also about the38 // Accord // ISSUE 27September 11 attacks three years later. Still, many amongthe Taliban leadership feared that Afghanistan would paythe price for the attack, and searched for a peacefulsolution. Many wanted bin Laden gone. However, even afteran Ulema conference in Kabul had advised that bin Ladenshould be asked to leave, Mullah Omar made it clear hewould not expel him.“The former warlords andparties to the civil war of the1990s won positions in thenew administration, usingtheir recently acquired powerto enrich themselves andtheir supporters.”The US, meanwhile, was mobilising rapidly in responseto 9/11. The Bush doctrine held that the US ‘will make nodistinction between those who planned these acts andthose who harbour them’. Operation Enduring Freedomlaunched in October 2001 saw the US use small teams ofspecial forces alongside Afghan opposition groups – whowere familiar faces to the Taliban. In north Afghanistan theUS built up the loosely affiliated groups of the NorthernAlliance, almost all of whom had been part of the civil warof the early 1990s. These included General MohammedFahim, who had been the intelligence officer of Ahmed ShahMassoud; Ismail Khan, who had carved out his own fiefdomin western Afghanistan; and the Uzbek commander AbdulRashid Dostum, who was notorious for switching allegiance.In the south, Gul Agha Shirzai, the same man the Taliban hadexpelled from Kandahar in 1994, mobilised men in Pakistanand marched towards Kandahar supported by US air power.The Taliban’s defeat by the US and the return to power oftheir old foes came as a shock. Overwhelming US airpowerhad been decisive. But the social contract of the IslamicEmirate had begun to dissolve well before then, as thepopular support the Taliban had once garnered had longstarted to dwindle in the light of new laws and policiesenforced by their government. In power, the Taliban’srelationship with the rural communities rehashed thesame struggle faced by all central authorities before them– to develop a working relationship with the peripheries.In particular, rural tribal communities were opposed togrowing interference in their local affairs by the Talibangovernment in Kabul. The opium ban that the Talibanenforced especially soured the relationship with manyrural farming communities by eroding their livelihoods.Following the swift demise of the Emirate, the shellshocked Taliban retreated, many returning to their home

villages and mosques and madrasas, others fleeing acrossthe border to Pakistan.In the first couple of years after the end of the Emirate itseemed that the Taliban were indeed a spent force. Manymembers of the senior leadership contemplated joiningthe new political paradigm in Kabul or returning to theirprevious lives before the movement. But it seemed thatthere was no safe space for them for them to demobilise.The US continued to pursue its war on terror, whileWashington’s Afghan allies used their newfound supportto settle old scores. The former warlords and partiesto the civil war of the 1990s won positions in the newadministration, using their recently acquired power toenrich themselves and their supporters. People who hadpreviously been close to the Taliban, or who were brandedas having been close, found themselves targeted.The return of the Taliban as a potent insurgent movementwould take a few years. Much like their first rise topower in the 1990s, their resurgence was facilitated bywidespread public discontent with the new government– the interim council headed by Hamid Karzai, and then hisadministration. As before, the new mobilisation compriseda conglomeration of local conflicts brought together underone umbrella by former Taliban leaders. Much time andeffort was invested in creating a coherent organisationthat would work within the Taliban’s framework. Theleadership circulated several rulebooks outlining rules andresponsibilities to be followed, the so-called Layeha. TheTaliban established a shadow government that looked tofeed off the failings of the corrupt government in Kabul andthe cultural ignorance of the foreign forces.Reconciliation?The Taliban questioned the Kabul government’s credibilityand legitimacy, seeing it as both installed and controlledby a foreign power. This is why the Taliban saw themselvesand the US as the real stakeholders in the growing conflictin Afghanistan – and hence in any reconciliation processtowards a political settlement. Their statement regardingthe 2009 election is illustrative:Our people surely remember that the Islamic Emiratealways maintained that the real decision about theresults of elections is made in Washington. Theelections are held to throw dust in the eyes of peopleand hide their colonialist agenda under the cloudof elections.The at times seemingly contradictory position of the UStowards the insurgency further complicated things. Forexample, under the Barrack Obama administration, whileSecretary of State Hillary Clinton endorsed the idea oftalks between the government in Kabul and the Taliban,President Obama announced a troop surge. Post-surgeefforts at reconciliation seemed to the Taliban little morethan an offer of amnesty in response to their capitulation.As a Taliban statement at the time reveals,contrarily, the Pentagon is at present makingpreparation for new military operations in Helmandprovince, south Afghanistan. Similarly, they putforward conditions, which are tantamount to escalatingthe war rather than ending it. For example, theywant the mujahedeen to lay down arms, accept theconstitution and renounce violence. Nobody can callthis reconciliation.Around the time of the surge, President Karzai was callingfor the Taliban to lay down their arms and join him. Hisgovernment established the High Peace Council (HPC) in2010, tasked with bringing about a reconciliation process,facilitating talks or in any other way supporting an end tothe conflict. The Taliban saw the HPC as little more thananother organ that worked under the command of theforeign forces. Mawlawi Kabir, a member of the Taliban’scentral council, explained a few months after the HPCwas founded that ‘[the] peace council is a one-sidedentity, having been established to protect their unilateralgoals and interests. The council consists of people whopractically support the Americans, though they claim beingjihadic figures and leaders. But by siding with the Americaninvaders, they had forfeited their credibility.’Negotiation has only made sense to the Taliban with peoplethey see as holding real power – ie the US. In June 2012the Taliban announced that they were ‘ready to open apolitical office abroad to reach a peaceful solution of theAfghan issue and understanding with the US’. Over the nextyear, the Taliban would repeat that it was the ‘US which isthe true independent counterpart to the Taliban. [ ] TheAmericans have been utilising the Karzai administrationas a tool for prolonging their occupation.’ A year later theTaliban opened a political office in Qatar, intended as amajor milestone in advancing a political process.The opening of the Qatar office turned into a diplomaticdisaster, however, with Taliban representatives speakingin front of the official flag of the Islamic Emirate. PresidentKarzai, who had been negotiating a bilateral securityagreement with the US, called off the negotiations andannounced that the HPC would not join talks in Qatar aslong as the peace process was not Afghan-led. This cameas a surprise to the Taliban who in a statement claimednot only that designating the office as an official agency ofthe Islamic Emirate had been agreed upon beforehand, butthat they would maintain their commitment to using theIncremental peace in Afghanistan // 39

office as a vehicle to talk with representatives of dozens ofcountries and members of the HPC. Karzai’s outrage overthe flag seemed another excuse to end the talks before theyhad started in earnest.Despite the breakdown of official contact, the US and theTaliban in 2014 agreed on a prisoner swap. Five Talibanprisoners were released from Guantanamo prison inexchange for Bowe Bergdahl, a US army soldier who hadbeen taken captive by the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2009.But while some hoped that the exchange would resultin more talks, little has materialised since. Looking atthe official communications of the Taliban, little seemsto have changed over the past eight years. In their eyes:Afghanistan continues to be occupied by foreign forces;the US determined the outcome of the disputed 2014election by negotiating the formation of the Nation UnityGovernment; new President Ashraf Ghani signed thebilateral security agreement with the US that allowedAmerican troops to stay in the country; and AbdullahAbdullah became Afghanistan’s first chief executive.The Taliban saw these changes as more of the same –an illegitimate and corrupt government propped upby the US and others.In a statement commemorating the 15-year anniversaryof Operation Enduring Freedom, the Taliban questionedthe foreigners’ achievement in relation to their statedgoals: to make Afghanistan self-sufficient; to end narcoticproduction and trade; to form a government accordingto the will of the Afghan nation; and to establish peace,stability and security in the country. The Taliban stressedthat, in fact, in the 15 years of US occupation much had gotworse: Afghanistan remained one of the poorest countriesin the world; drug production was at a record high; thegovernment in Kabul seemed one of the most corrupt inthe world, ‘run by thieves and gangs of evil’; and securityand justice were non-existent.ConclusionIn 2015 it was revealed that Mullah Omar, the founder andleader of the Taliban, had died two years earlier. A small40 // Accord // ISSUE 27group of Taliban leaders had pretended he was still aliveand had ruled in his stead. The news of his death sawMullah Mansour become leader, but the accompanyingleadership struggle meant that the enduring differencesbetween the various Taliban networks now began todevelop cracks and then the first signs of actual ruptures.A year later, Mullah Rasool announced the first splintergroup. Mansour managed to consolidate his hold over thewider movement and introduced significant innovations,even suggesting that he was not ruling out a politicalsolution to the Afghan conflict. But the US assassinatedhim in May 2016. Mawlawi Haibatullah Akhundzada becamethe next Amir of the Taliban. Meanwhile, the Islamic State,having achieved international notoriety Iraq and Syria, hadstarted to branch out. The formation of the Islamic State inthe Khorasan (ISK) in eastern Afghanistan was announcedin 2015. Arguably an outcome of increased internal strifeamong different jihadi and other militant groups, ISK grewinto a formidable foe of the Taliban, which soon found itselfin open conflict with the newly formed group.The Taliban today draw parallels with the situation in theearly 1990s when Afghanistan descended into civil war. Theysee many of the same people in powerful positions aroundthe country, as well as a comparable local security situationand similarly unacceptable behaviour by security forces.The Taliban’s narrative of Afghanistan’s history casts themin the role of righteous victims. In many ways the Talibanare less exceptional in Afghanistan than many would likethem to be. Many of their messages echo the grievances ofa significant section of Afghan society, and they remain theexpression of a much broader discontent that is anchored inlocal conflict. No group can survive in Afghanistan withoutlocal support, support which can never be won by fear alone.This reality is abundantly clear from the failure of everyAfghan government to extend its reach into the hinterlands.And it shows that the Taliban’s narrative of the conflict inAfghanistan is not an alternative version of Afghanistan’shistory, but rather a missing piece of the larger puzzle ofhow to administer the country peacefully – a piece thatremains ignored by much of the West.

Incremental peace in Afghanistan // 35 Taliban history of war and peace in Afghanistan Felix Kuehn Felix Kuehn is the co-editor of My Life with the Taliban, the autobiography of the former Taliban envoy to Pakistan, Mullah