Transcription

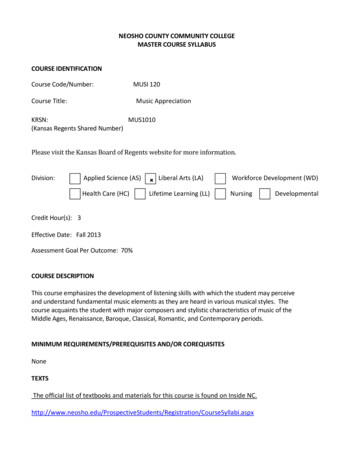

Music theoryHandbook VOL 13““6““10““13““16““Getting Started with Counterpoint”From the Online Course Counterpointby Beth DenischUnderstanding Reharmonization”From the Online Course Reharmonization Techniquesby Steve RochinskiMaster the Basics of Rhythm”From the Online Course Music Theory 101by Paul SchmelingLearn the Intricacies of the Seventh Chord”From the Online Course Getting Inside Harmony 1by Michael RendishExamining the Theory Behind the Blues”From the Online Course Music Theory 201by Paul Schmeling

Getting Started with CounterpointFrom the Online Course Counterpointby Beth DenischBeth Denisch is a professor in the Composition Department at Berklee College of Music.Her music has been performed throughout the U.S. and in Canada, Mexico, Greece, Ukraine,Russia, China, and Thailand, and recorded by Juxtab, Albany, and Interval record labels.Consider music from the Medieval,an effective melodic line and 2) both linesRenaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic,stand together, keeping their independence,and 20th century periods.but also creating a great sound when heardWhat connects these diverse musicaltogether. This is counterpoint.eras? It is the use of multiple melodic lines toThe term texture is used to describe thecreate effective music. This is counterpoint.relative “thickness” or “thinness” of musicalThe term counterpoint refers to two or moresound. Musical textures, like the texture ofindependent melodic lines working togetherfabric, can be rough or smooth, simple orto create music. In contrapuntal music—complex, dense or sparse. Here are threemusic created using counterpoint—each ofbasic musical textures, only one of whichthe melodies works independently as welldefines counterpoint:as together. Together these melodies create1.a texture called polyphony. Polyphony andMonophony—A solo melody, just oneline of music. This is the simplest musicalcounterpoint have been around for abouttexture. (From the Greek: mono—one;1,000 years and are at the root of melodyand phony—sound or voice.) Commonand harmony in Western music.monophonic performances include a soloYou may already be thinking about howsinger or performer on a monophonicgood it sounds in contemporary popularinstrument like a flute or trumpet.music when the bass and lead lines complement each other just right. This happens2.when 1) each line stands independently aschords, like a song; a harmonized3Homophony—A melody with

melody. The chordsCounterpoint(harmonies) dohas been evolving innot stand on theirWestern music forown as indepen-about 1,000 years.dent melodies butOne of the earliestare heard as soundexamples is found inshapes supportingthe Winchester Troperor “harmonizing”from the 11th century,the single melody,andoften in the samewritingrhythm as themelody. (From theA portion of the Winchester Tropercontrapuntalcontinuestoday, as in themusic of EstonianGreek: homo—same; and phony—soundcomposer Arvo Pärt. Today, counterpoint isor voice.) Homophony is the dominanteverywhere, even in popular music. Its influ-texture of contemporary music. Theence can be heard in pop music such as themajority of rock music consists of aBeatles’ “Paperback Writer,” progressivemelody sung by a lead vocalist over arock artists like Emerson, Lake & Palmer andchordal background provided by theKing Crimson, and even in the musiqueband.concrète aspects of hip-hop.3.Taking a contrapuntal perspective onPolyphony—More than one melodymusic means that you are looking at ithappening at the same time. For example,horizontally—via melody—but are also tak-in “Canto di Bella Bocca,” by Barbaraing into consideration the vertical (harmonic)Strozzi, you can hear two vocal melodiessounds or implications of this simultaneousworking together to create beautifulmelodic motion.harmonies while at the same time main-Still, the texture of counterpoint remains:taining their melodic independenceTwo or more melodic layers maintain theirfrom each other. That is, multiple layersindependence while creating desirableare heard separately and simultaneously.harmonies.This is called polyphony. (From theFind a piece of music you like and thinkGreek: poly—many; and phony—soundof at least two of the topics that generallyor voice.)describe the sound of your selection. ForCounterpoint will always occur as aexample, you might say the music is homo-polyphonic texture. The term counterpointphonic and consonant, as in a “pretty” songcomes from the Latin “punctus contra punc-with melody and simple chords. Or you maytum,” meaning note against note (pointsay the heavy metal guitar solo is dissonantagainst point).and polyphonic with the bass guitar.4

Consonancevs.DissonanceWhat is consonant and what is dissonant? There is no absolute answer to this question.Consonance and dissonance, and the many variations across this spectrum of apparentpolar opposites, are only defined by the common practices found in each particular styleof music.Consonance, in general, refers to a pleasant sound, something that is at rest,comfortable. Dissonance, on the other hand, refers to tension and instability, a sense thatthe music needs to “go somewhere” for resolution.Beth Denisch’s Online CoursesCounterpointThis course uses musical examples from the Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, Classical,Romantic, and 20th century periods, in addition to relevant examples from contemporarypopular artists and styles. You’ll have access to a timeline from which you can see thechronological and geographical placement of musical examples as you listen to them.Throughout the course, you will strengthen your music listening, reading, and writing skillsthrough hands-on writing activities. The goal of the course is to give you a broad overview ofcounterpoint and improve your compositional skills, regardless of stylistic preference.5

Understanding ReharmonizationFrom the Online Course Reharmonization TechniquesBy Steve RochinskiSteve Rochinski is a Professor in the Harmony Department at Berklee College of Music. Anaccomplished guitarist, recording artist, and internationally known performer and clinician,Steve has received numerous grants and awards including a 1993 Jazz Fellowship from theNational Endowment for the Arts for private study with Tal Farlow.When the late jazz guitar legend TalThere are instances in which the rehar-Farlow explained his motivation to rehar-monized song is considered so superior tomonize standard tunes, he replied with thisthe original chord changes that the newtwist on an old adage: “If it ain’t broke, fixversion becomes the standard harmonicit anyway.” And so it goes. In the world ofform—which, in turn, becomes subjectedartists of all mediums and disciplines, theto further variation. The Victor Young clas-musician is most audacious when it comessic “Stella By Starlight” and the Burke/Vanto altering another’s creation. Imagine anHeusen standard “Like Someone In Love”artist taking a palette of paints and a brushare excellent examples of “new” standards.to the Museum of Fine Arts and painting anCan you imagine what a cocktail pianist,extra nose on a Picasso masterpiece? Orwho has been on the same five-night-a-weeksomeone putting a hat on Rodin’s timelessgig for ten years, would have to endure ifbronze and marble sculpture The Thinker?some kind of harmonic liberty was not takenScandalous, to say the least . . . and possiblywith the repertoire? Maybe reharmoniza-resulting in some jail time!tion contributes to good mental health forHowever, the history of jazz performancethe performer. No matter how you frame it,and arranging, as well as European classicalreharmonization has a long-standing tradi-tradition, as exemplified by Rhapsody on ation in the world of jazz and popular music.Theme of Paganini by Rachmaninoff, is filledSo specifically, why reharmonize?with players and writers whose creative inten-Occasionally, there is a need to usetion could be distilled down to Tal’s response.material from the standard repertoire where6

reharmonization can place the ordinary intoFor a reharmonization to be acceptablean extraordinary setting. There may also beto the listener, there are two relatively abso-situations in which the melody and chordslute conditions:may not be in vertical agreement—a changein the harmony may be called for.For the improvising player, reharmonization is regarded as improvising harmonies tois resourced from common practice chordof the chord changes of a tune, the variouslearned in this courseandsuperimposedagainst the rhythmsection accompaniment can be appliedto great effect.patterns of standard“To reharmonize means toalter the underlying harmonicform of a piece of music, whilemaintaining the original melodicstructure.”conditions, but untilfurther notice, thesewill be absolutes.Dependingonprogressions that may be more limited thanture. It is essentially an arranging applicationthose of the professional musician. The morewhere the primary focus is on the harmony,experienced the listener, the more complex awhether done on paper or in real time.reharmonization can be and still be acceptable.Reharmonization alters the mood of aUltimately, for the listener to accept thesong by:new harmonization as valid, arbitrary chordincreasing tension and releasechoices must be avoided.There are several levels on which to mea-through substitution and approachsure the effects of reharmonization. One oftechniquesthree outcomes can be expected with rehar-prolonging expectations for resolu-monization relative to the harmonic rhythm:tion of nontonic functions1.creating a more, or in some cases,The original harmony will besubstituted through structural con-less active harmonic stream exceptions to thesea catalog of common, internalized harmonicwhile maintaining the original melodic struc- There will always beexperiences, the average non-musician hasunderlying harmonic form of a piece of music, popular repertoire.his or her listeningTo reharmonize means to alter the The harmony must be logical andembellishment is used and the harmonying melodically within the standard frameworktechniques2.This means that little or no melodicimprovisation. For the improviser who is solo-proachThe melody must be recognizable.familiar.a fixed melody line—the opposite of melodicsubstitution and ap-1.version and with chords of a similarenhancing the bass linefunction—in most cases, there’s no7

change in the harmonic rhythm. (There3.will be exceptions.)modified by removing chords—the2.harmonic rhythm may become slower.The original harmony will haveapproach chords added that have eitherThe original harmony will beHere are several versions of a populara functional or a structural relationshipbirthday song originally titled “Goodwith an original target chord—theMorning To You.”harmonic rhythm becomes faster.The first version is harmonized with the original chords.The second version is reharmonized with simple, substitute diatonic chords. There’s nochange in the harmonic rhythm.The third version is reharmonized with approach chords, along with 6th and 7th chords toenrich the triads, resulting in a more active harmonic rhythm.8

The final version is a reharmonization using a combination of substitute and approachtreatments. This creates a very active and colorful harmonic support with the majority of themelody notes harmonized with a different chord.If you can, try playing these melodies. How would you describe the emotional differencesbetween them?Steve Rochinski’s Online CoursesReharmonization TechniquesReharmonization Techniques teaches where and how to approach changing the harmonicform, especially in the context of historical stylized treatments. You will learn to make acreative judgment about how much or how little to change a song and then make logical,creative choices to achieve that outcome. The course begins with an historical overview ofreharmonization techniques and moves quickly into using basic substitution techniques (e.g.,tonic for tonic, subdominant for subdominant, dominant for dominant, and so forth) in selectedareas of the form. It then expands into bass line reharmonization and the various approachtechniques covering larger sections of the song, techniques such as diatonic and dominantapproaches relative to a target chord and chromatic and parallel approaches relative to atarget chord.9

Master the Basics of RhythmFrom the Online Course Music Theory 101By Paul SchmelingPaul Schmeling is a master pianist, interpreter, improviser, and arranger who has inspiredcountless students since he began teaching at Berklee in 1961. He has performed or recordedwith jazz greats such as Clark Terry, Rebecca Parris, George Coleman, Carol Sloane, FrankFoster, Art Farmer, Herb Pomeroy, Phil Wilson, Dick Johnson and Slide Hampton.Rhythm is the aspect of music relating toWhat are some other examples of 2, 3, ortime—when musical events happen (notes4 pulse words? What about a 5 pulse word?and other sounds) in relation to other musi-Which syllable has the downbeat?cal events.When beats are grouped together, theA regular pulse is fundamental to musicpulse is said to be in meter. Most music hasand some pulses or beats are emphasizeda regular underlying meter. Each group ofmore than others. Say the word “alligator.”beats is called a measure or bar. In musicNotice that “al” has the strongest empha-notation, meter is indicated by a time sig-sis. The strongest beat is beat 1 (“al”) andnature. A time signature usually has twois called the downbeat. Beat 3 (“ga”) isnumbers, one above the other. The topalso considered a strong beat, althoughnumber indicates how many beats are innot as strong as beat 1. Say “alligator” overeach measure. For example:and over, keeping the beat regular and onIn this time signature,each syllable. Notice how the beats arethere are four beats per measure.grouped into sets of four. Now, say “crocodile” over and over. Here, the beats areIn this time signature,grouped into sets of three. The downbeatthere are three beats per measure.is on the syllable “croc.” Next say “lizard”In this time signature,over and over. What do you notice? Yes,beats per measure.“lizard” has 2 beats. The downbeat is onthe syllable “liz”.10there are two

Let’s focus on the 4/4 time signature, orQuarter notes last for a quarter of aas it is also called, common time (C). Thiswhole note: one beat. Their symbol is ais the most common meter in popular andclosed notehead with a stem.jazz music.Each note value has a correspondingrest symbol, which indicates silence forBar lines separate measures, and thethat value. Let’s look at three types of rests:music ends with a final bar line—a thin andwhole, half, and quarter rests:thick line. Notes are the building blocks of music.Whole rests are small, solid rect-They can last for any number of beats—weangles that hang down from a staff line.will refer to this as the note’s duration or value.They represent four beats of silence.Each note value represents a rhythmicIf the whole measure is silent, a wholeattack. Let’s look at three common types ofrest is also used, regardless of the timenote values: whole, half, and quarter notes:signature. Whole notes last for a whole mea-sure in common time, which is fourbeats. The symbol for a whole note is an open notehead.Half rests are rectangles that lieon top of a staff line. They last for twobeats. Half notes last for half as long aswhole notes: 2 beats. Their symbol is an open notehead with a vertical line calledQuarter rests look like a sideways Wwith a thick middle. They last for one beat.a stem.Think about setting these words to music: “Yesterday is history; tomorrow a mystery.”Which syllables should be stressed? What meter would they best fit into? How manymeasures would be required?11

Paul Schmeling’s Online CoursesMusic Theory 101Join our community of beginning learners for engaging, hands-on activities that will help youread, write, and truly hear the elements of music like never before.Music Theory 201: Harmony and FunctionThrough ear training exercises, musical examples, and personalized feedback from yourinstructor, you’ll be able to analyze, read, write, and listen more effectively as well as understandthe fundamental knowledge essential to the beginning studies of harmony.Music Theory 301: Advanced Melody, Harmony, RhythmEstablish a toolkit of musical expertise that will prepare you for any musical endeavor oropportunity. This advanced music theory course provides you with a professional commandof the mechanics of contemporary music.12

Learn the Intricacies of theSeventh ChordFrom the Online Course Getting Inside Harmony 1By Michael RendishMichael Rendish is the former Assistant Chair of Berklee College of Music’s Film ScoringDepartment. A gifted performer and award-winning writer, he has composed, orchestrated,and conducted some thirty film scores, including Faces of Freedom, A Place of Dreams,Yorktown, and the five-part PBS series America by Design.Beyond the basic 1–3–5 triad, how canPicture what kind of third, what kind ofwe further add spice to our harmonies?fifth, and what kind of seventh occur aboveHow do all those jazz musicians create suchthe root when the chord is in close, rootinteresting and groovy sounds?position.The answers to these questions lie inThere are four kinds of seventh chordseventh chords, a vital part of your harmonicfound on the degrees of the major scale:vocabulary. The seventh chord forms anmajor seventh, minor seventh, dominantessential harmonic “ribcage” for your music,seventh, and minor seventh (5).as we’ll see. Seventh chords come in several different varieties, each serving distinctmusical functions.Think of a seventh chord as an upwardextension of a triad. The chord members,Major 7thChord hen, are the root, third, fifth, and seventh. 13Minor 7thChord TypeSymbol3rd5th7thminor7thG–7minorperfectminor

Dominant 7thMinor 7(b5)Chord TypeSymbol3rd5th7thChord inor7(b5)G–7(b5)minordiminishedminorLet’s see what kind of seventh chords we find on each degree of the major scale. Buildinga diatonic seventh chord above each scale degree in C major, we get:In summary, then, we find thefollowing types of seventh chordsdiatonic to the major scale: Major7th on I and IV Minor7th on II, III, and VI Dominant7th on V Minor7( b 5) on VIIWhy might the term position rather than inversion be more appropriate when referring toany of the various ways a chord’s notes can be arranged?The notes of any standard chord (triad or seventh) are defined. A Cmaj7 will alwayscontain a C, an E, a G, and a B. However, those notes may be positioned a number of differentways. Take a look at the following:14

These are all Cmaj7 chords. All of theseAnd, as with triads, identifying seventhversions (and many others) are used all thechords is simply a matter of reordering the notetime. As it was with triads, it’s an importantnames until you get a sequence of thirds—thispart of your chord recognition skill to betime, three consecutive thirds. You then haveable to identify seventh chords in no matterthe chord in root position, so it’s now merelywhat order the notes may appear.a matter of noting the kind of third, fifth, andseventh in order to identify the chord.Michael Rendish’s Online CoursesGetting inside harmony 1Through a combination of activities (listening, thinking, visualizing, vocalizing, writing, andplaying), you’ll open your ears and deepen your understanding of the inner workings ofharmony in a broad range of contemporary styles. You’ll find that you learn songs more easilyand can transpose them on sight. And you’ll be able to equip yourself with the best chordscale choices for arranging and improvising.Getting inside harmony 2Through keyboard chord voicings and voice-leading exercises, you’ll gain an understandingof the musical tools that go beyond the demands of a particular musical style, and developa greater sense of control in your writing - by the end of the course you’ll find you’re in aposition to actually contribute your personal touch to the development of any number ofmusical styles!15

Examining the Theory Behindthe BluesFrom the Online Course Music Theory 201By Paul SchmelingPaul Schmeling is a master pianist, interpreter, improviser, and arranger who has inspiredcountless students since he began teaching at Berklee in 1961. He has performed or recordedwith jazz greats such as Clark Terry, Rebecca Parris, George Coleman, Carol Sloane, FrankFoster, Art Farmer, Herb Pomeroy, Phil Wilson, Dick Johnson and Slide Hampton.From B.B King to Stevie Ray Vaughan, the blues permeate the history of music, particularly in America. The influence of the blues is continually felt in any number of songs in thepop, rock, funk, fusion, and jazz styles. A working knowledge of the blues is a fundamentalpart of a solid theoretical background.Let’s take a look at the blues form and style—an essential part of the pop and jazzmusician’s vocabulary.Blues is a twelve-measure form divided into three four-measure phrases. Regardless ofstyle and degree of harmonic sophistication, all blues have the same harmonic functionsoccurring in the same places within the form. Blues must have at least this amount of, andplacement of, harmonic activity to be considered the blues.16

The most common variations of these basic harmonies are found in measures 9–10, thearea of the dominant function, where the dominant chord may be followed or preceded bythe subdominant. The other common variation is a subdominant chord in measure 2 andthen a quick return to tonic in measure 3. Both of these variations are shown in the followingexample.Before we move on to the actual chords commonly used in blues progressions, let’s translate the function names into chord roots using the strongest of each function group. The tonicfunction will be the I chord; the subdominant function, the IV chord; and the dominant function, the V chord. Putting these chords into the key of F, the basic chords of blues would looklike this:17

The term blues can be used to identify a musical form, as we have just discussed, or itcan be used to identify a style, which we are going to look at next. Often the two are usedtogether (both blues form and style), but sometimes a blues form may have a melody andchords that do not sound blues-like. Also, a song that is not a blues form can be made tosound “bluesy” by the use of the “blues notes.”The blues notes, as you superimpose them over a major scale, are the flatted 3rd, theflatted 5th, and the flatted 7th. Their origin is in vocal music, where these flatted notes werevocal inflections or bendings of the pitch.The most immediate and obvious influence the blues notes have is their effect on theharmony of a blues progression. Going back to the basic I, IV, and V chords discussed earlier,it is common that the I chord is a dominant 7th chord, as the b7 (Eb) is used as part of thechord. Similarly, the IV chord is also a dominant 7th as it uses the b3 (Ab) as its 7th. The Vchord is already a dominant 7th chord as a diatonic chord in the F major scale.Even the choice of tensions is often affected by the blues notes. The I chord frequentlyuses #9, and the V chord frequently uses the b13—both using the b3 (A b). The b5 can showup as the b9 of the IV7 chord or the #11 on the I7 chord, but obviously won’t work on the V7.The following sums up the potential use of the blues notes as tensions on the three chords ofthe basic blues progression.18

The blues notes (b3, b5, b7) may be used in addition to, or instead of, the regular 3rd, 5th,and 7th from the major scale, but the most common blues scale is the following. Notice thatthe flatted 3rd and 7th are used instead of the regular 3rd and 7th, but the flatted 5th is usedin addition to the natural 5th.This same scale may be used over the three basic chords of a blues progression, eventhough not every note of the scale “fits” on each of the chords. The sound of the blues scaleis strong enough to override these concerns.The three four-measure phrases of the blues form are typically set up to be a four-measurephrase repeated in measures 5–8 and somehow varied in measures 9–12. Notice, in thefollowing blues melody, the use of the blues notes, as well as the three four-measure phrases.The second phrase repeats the first, and the third phrase is similar to the first but changed alittle for variation purposes.19

Paul Schmeling’s Online CoursesMusic Theory 101Join our community of beginning learners for engaging, hands-on activities that will help youread, write, and truly hear the elements of music like never before.Music Theory 201: Harmony and FunctionThrough ear training exercises, musical examples, and personalized feedback from yourinstructor, you’ll be able to analyze, read, write, and listen more effectively as well as understandthe fundamental knowledge essential to the beginning studies of harmony.Music Theory 301: Advanced Melody, Harmony, RhythmEstablish a toolkit of musical expertise that will prepare you for any musical endeavor oropportunity. This advanced music theory course provides you with a professional commandof the mechanics of contemporary music.20

Online COurses in MUSIC THEORYStudy with the renowned faculty of Berklee Collegeof Music from anywhere in the world, with onlinecourses at Online.Berklee.comONLINE COURSES Music Theory 101 Music Theory 201: Harmony andFunction Music Theory 301: AdvancedMelody, Harmony, Rhythm Basic Ear Training 1 Getting Inside Harmony 1 Getting Inside Harmony 2 Harmonic Ear Training Counterpoint Reharmonization TechniquesCERTIFICATE PROGRAMSMASTER CERTIFICATES(8-12 COURSES) Theory, Harmony, and Ear TrainingSPECIALIST CERTIFICATES(3 COURSES) Music Theory Music Theory and Counterpoint Theory and Harmony Voice Technique and Musicianship

create effective music. This is counterpoint. The term counterpoint refers to two or more independent melodic lines working together to create music. In contrapuntal music— music created using counterpoint—each of the melodies works independently as well as together. Together these melodies create a texture called polyphony. Polyphony and