Transcription

U.S. Department of JusticeOffice of Community Oriented Policing ServicesProblem-Oriented Guides for PoliceProblem-Specific Guides SeriesNo. 1Assaults in andAround Bars2 nd E d i t i o nbyMichael S. ScottKelly Dedelwww.cops.usdoj.gov

Center for Problem-Oriented PolicingGot a Problem? We’ve got answers!www.PopCenter.orgLog onto the Center for Problem-Oriented Policing web siteat www.popcenter.org for a wealth of information to helpyou deal more effectively with crime and disorder in yourcommunity, including: Web-enhanced versions of all currently available Guides Interactive training exercises Online access to research and police practices Online problem analysis module.Designed for police and those who work with them toaddress community problems, www.popcenter.org is a greatresource in problem-oriented policing.Supported by the Office of Community Oriented PolicingServices, U.S. Department of Justice.

Problem-Oriented Guides for PoliceProblem-Specific Guides SeriesGuide No. 1Assaults in andAround Bars2nd EditionMichael S. ScottKelly DedelThis project was supported by cooperative agreements#1999CKWXK004 and 2005CKWXK001 by the Office ofCommunity Oriented Policing Services, U.S. Department of Justice.The opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) and do notnecessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Departmentof Justice. References to specific companies, products, or servicesshould not be considered an endorsement thereof by the author(s)or the Justice Department. Rather, the references are illustrations tosupplement discussion of the issues.www.cops.usdoj.govISBN: 1-932582-00-2August 2006

About the Problem-Specific Guides SeriesAbout the Problem-Specific GuidesSeriesThe Problem-Specific Guides summarize knowledge abouthow police can reduce the harm caused by specific crimeand disorder problems. They are guides to preventionand to improving the overall response to incidents, notto investigating offenses or handling specific incidents.Neither do they cover all of the technical details abouthow to implement specific responses. The guides arewritten for police—of whatever rank or assignment—whomust address the specific problem the guides cover. Theguides will be most useful to officers who: Understand basic problem-oriented policingprinciples and methods. The guides are not primers inproblem-oriented policing. They deal only briefly with theinitial decision to focus on a particular problem, methodsto analyze the problem, and means to assess the resultsof a problem-oriented policing project. They are designedto help police decide how best to analyze and address aproblem they have already identified. (A companion seriesof Problem-Solving Tools guides has been produced to aid invarious aspects of problem analysis and assessment.) Can look at a problem in depth. Depending on thecomplexity of the problem, you should be prepared tospend perhaps weeks, or even months, analyzing andresponding to it. Carefully studying a problem beforeresponding helps you design the right strategy, one that ismost likely to work in your community. You should notblindly adopt the responses others have used; you mustdecide whether they are appropriate to your local situation.What is true in one place may not be true elsewhere; whatworks in one place may not work everywhere.

iiAssaults in and Around Bars, 2nd Edition Are willing to consider new ways of doing policebusiness. The guides describe responses that other policedepartments have used or that researchers have tested.While not all of these responses will be appropriate toyour particular problem, they should help give a broaderview of the kinds of things you could do. You may thinkyou cannot implement some of these responses in yourjurisdiction, but perhaps you can. In many places, whenpolice have discovered a more effective response, they havesucceeded in having laws and policies changed, improvingthe response to the problem. (A companion series ofResponse Guides has been produced to help you understandhow commonly-used police responses work on a variety ofproblems.) Understand the value and the limits of researchknowledge. For some types of problems, a lot of usefulresearch is available to the police; for other problems,little is available. Accordingly, some guides in this seriessummarize existing research whereas other guides illustratethe need for more research on that particular problem.Regardless, research has not provided definitive answers toall the questions you might have about the problem. Theresearch may help get you started in designing your ownresponses, but it cannot tell you exactly what to do. Thiswill depend greatly on the particular nature of your localproblem. In the interest of keeping the guides readable,not every piece of relevant research has been cited, nor hasevery point been attributed to its sources. To have done sowould have overwhelmed and distracted the reader. Thereferences listed at the end of each guide are those drawnon most heavily; they are not a complete bibliography ofresearch on the subject.

About the Problem-Specific Guides Series Are willing to work with others to find effective solutionsto the problem. The police alone cannot implement many ofthe responses discussed in the guides. They must frequentlyimplement them in partnership with other responsibleprivate and public bodies including other governmentagencies, non-governmental organizations, private businesses,public utilities, community groups, and individual citizens.An effective problem-solver must know how to forgegenuine partnerships with others and be prepared to investconsiderable effort in making these partnerships work.Each guide identifies particular individuals or groups inthe community with whom police might work to improvethe overall response to that problem. Thorough analysis ofproblems often reveals that individuals and groups otherthan the police are in a stronger position to address problemsand that police ought to shift some greater responsibility tothem to do so. Response Guide No. 3, Shifting and SharingResponsibility for Public Safety Problems, provides furtherdiscussion of this topic.The COPS Office defines community policing as “a policingphilosophy that promotes and supports organizationalstrategies to address the causes and reduce the fear of crimeand social disorder through problem-solving tactics andpolice-community partnerships.” These guides emphasizeproblem-solving and police-community partnerships inthe context of addressing specific public safety problems.For the most part, the organizational strategies that canfacilitate problem-solving and police-community partnerships varyconsiderably and discussion of them is beyond the scope ofthese guides.These guides have drawn on research findings and policepractices in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada,Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia.iii

ivAssaults in and Around Bars, 2nd EditionEven though laws, customs and police practices varyfrom country to country, it is apparent that the policeeverywhere experience common problems. In a world thatis becoming increasingly interconnected, it is importantthat police be aware of research and successful practicesbeyond the borders of their own countries.Each guide is informed by a thorough review of theresearch literature and reported police practice and isanonymously peer-reviewed by line police officers, policeexecutives and researchers prior to publication.The COPS Office and the authors encourage you toprovide feedback on this guide and to report on yourown agency’s experiences dealing with a similar problem.Your agency may have effectively addressed a problemusing responses not considered in these guides and yourexperiences and knowledge could benefit others. Thisinformation will be used to update the guides. If you wishto provide feedback and share your experiences it shouldbe sent via e-mail to cops pubs@usdoj.gov.For more information about problem-oriented policing,visit the Center for Problem-Oriented Policing online atwww.popcenter.org. This web site offers free online accessto: the Problem-Specific Guides series the companion Response Guides and Problem-Solving Tools series instructional information about problem-oriented policingand related topics an interactive problem-oriented policing training exercise an interactive Problem Analysis Module a manual for crime analysts online access to important police research and practices information about problem-oriented policing conferencesand award programs.

AcknowledgmentsAcknowledgmentsThe Problem-Oriented Guides for Police are produced by theCenter for Problem-Oriented Policing, whose officers areMichael S. Scott (Director), Ronald V. Clarke (AssociateDirector) and Graeme R. Newman (Associate Director).While each guide has a primary author, other projectteam members, COPS Office staff and anonymous peerreviewers contributed to each guide by proposing text,recommending research and offering suggestions onmatters of format and style.The project team that developed the guide seriescomprised Herman Goldstein (University of WisconsinLaw School), Ronald V. Clarke (Rutgers University),John E. Eck (University of Cincinnati), Michael S. Scott(University of Wisconsin Law School), Rana Sampson(Police Consultant), and Deborah Lamm Weisel (NorthCarolina State University.)Members of the San Diego; National City, California; andSavannah, Georgia police departments provided feedbackon the guides’ format and style in the early stages of theproject.Cynthia E. Pappas oversaw the project for the COPSOffice. Research for the guide was conducted at theCriminal Justice Library at Rutgers University under thedirection of Phyllis Schultze. Suzanne Fregly edited thisguide.

ContentsContentsAbout the Problem-Specific Guides Series . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iAcknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vThe Problem of Assaults in and Around Bars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1Related Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Factors Contributing to Aggression and Violence in Bars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Alcohol . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Culture of Drinking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Type of Establishment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Concentration of Bars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Bar Closing Time. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Aggressive Bouncers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6High Proportion of Young Male Strangers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Price Discounting of Drinks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Continued Service to Drunken Patrons. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Crowding and Lack of Comfort. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8Competitive Situations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8Low Ratio of Staff to Patrons. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Lack of Good Entertainment. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Unattractive Décor and Dim Lighting. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Tolerance for Disorderly Conduct. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Availability of Weapons. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Low Levels of Police Enforcement and Regulation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10Understanding Your Local Problem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Stakeholders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Asking the Right Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Incident Characteristics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Victims . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Offenders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Locations/Times. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14Bar Management Practices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14Regulations and Enforcement Practices. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15vii

viiiAssaults in and Around Bars, 2nd EditionMeasuring Your Effectiveness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16Responses to the Problem of Assaults in and Around Bars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17General Requirements of an Effective Strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17Specific Responses to Reduce Assaults . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20Reducing Alcohol Consumption . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Making Bars Safer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24Responses With Limited Effectiveness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29Appendix: Summary of Responses to Assaults in and Around Bars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Endnotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41About the Authors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55Recommended Readings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57Other Problem-Oriented Guides for Police. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

The Problem of Assaults in and Around BarsThe Problem of Assaults in andAround Bars§This guide deals with the problem of assaults in andaround bars.§ We know a lot about the risk factors forthese assaults, and about effective responses to them.We know less about which particular responses are mosteffective in addressing specific aspects of the problem.Therefore, your challenge will be to conduct a goodanalysis of the local problem, guided by the informationpresented here, and put together the right combination ofresponses to address that problem.§§The guide begins by reviewing factors that increase therisks of assaults in and around bars. It then identifies aseries of questions that might help you analyze your localproblem of assaults in and around bars. Finally, it reviewsresponses to the problem, and what is known about themfrom evaluative research and police practice.The proliferation of bars in many communities has ledto increases in assaults in and around the bars. Whilemany, if not most, of these are alcohol-related, assaultsalso occur when neither the aggressors nor the victimshave been drinking. Most assaults occur on weekendnights.1 The majority of assaults occur at a relatively smallnumber of places.2, §§ Not all assaults involve a simplefistfight with a clear beginning and ending; instead, theincidents are often more ambiguous and complicated.For example, some are intermittent conflicts that flareup over time, some evolve into different incidents, andmany involve participants who alternate between the rolesof aggressor and peacemaker, often drawing additionalpeople into the incident.3 Some involve lower levels of The term “bar” refers to licensedliquor establishments that sellalcohol primarily for consumptionon the premises. These includeestablishments variously known asnightclubs, pubs, taverns, lounges,hotels (in Australia), discotheques,or social clubs. The term “assault”refers to the full range of violentacts, from those that cause minorinjury to those that cause death,and from consensual fights tounprovoked attacks.For example, in Sydney, Australia,just 12 percent of bars accountedfor almost 60 percent of assaultsoccurring in licensed drinkingestablishments (Briscoe andDonnelly 2001b).

Assaults in and Around Bars, 2nd Editionaggression (pushing, shoving), some involve more-severeviolence (kicking, punching), and still others involve theuse of weapons. Many of the injuries treated at hospitals,especially facial injuries, are related to assaults in andaround bars.Those who fight in bars are not deterred by negativeconsequences (such as minor injuries, tension amongfriends, or trouble with the police), all of which tend tobe delayed. The perceived rewards are more immediateand include feeling righteous about fighting for a worthycause, increasing group cohesion among friends, gettingattention, feeling powerful, and having entertaining storiesto tell.4 Although some assault victims do something toprecipitate the assault, many do not. 5 Most are smallerthan their attackers, are either alone or in a small group,and are drunk more often than their attackers. 6 Attackerstarget victims who appear drunker than themselves. 7Many assaults are not reported to the police by either barstaff or the victim. Bar owners have mixed incentives forreporting assaults to the police. On the one hand, theyneed police assistance to maintain orderly establishments,but on the other hand, they do not want official recordsto reflect negatively on their liquor licenses. Many fightsand disputes that start inside a bar are forced outsideby the staff so they do not appear to be connected withthe bar. Victims often are drunk, are ashamed, and seethemselves as partly responsible, and so do not reportassaults. Other victims believe the incidents are too trivialto involve the police.8 Thus police records do not reflectthe total amount of violence in and around bars. However,we underestimate the seriousness of the problem if webelieve these assaults are just excessive exuberance byyoung men or “just deserts” for drunken troublemakers.

The Problem of Assaults in and Around BarsIn addition to generating police and community concernsfor public safety, bar owners also bear the consequencesof the problem in terms of damage to reputations, lossof future customers, staff reluctance to work, damage toproperty, reductions in profit, and, ultimately, potentialloss of license.9Related ProblemsAssault is only one of many alcohol- and bar-relatedproblems the police must address. Some of these issuesare covered in other guides in this series. These relatedproblems require their own analyses and responses: assaults around bars motivated by racial, ethnic, sexualorientation, or other bias binge drinking on college campuses disorderly conduct of public inebriates who drink inbars (e.g., panhandling, public urination, harassment,intimidation, and passing out in public places) drug dealing in bars drunken driving by customers leaving bars§ gambling in bars illegal discrimination against bar patrons prostitution in bars sexual assaults in and around bars underage drinking.§§§See Problem-Specific GuideNo. 36, titled Drunk Driving.§§See Problem-Specific GuideNo. 27, titled Underage Drinking.

Assaults in and Around Bars, 2nd EditionFactors Contributing to Aggression andViolence in BarsUnderstanding the factors that are known to contributeto your problem will help you frame your own localanalysis questions, determine good effectivenessmeasures, recognize key intervention points, and select anappropriate set of responses for your particular problem.AlcoholDrinking alcohol is the most obvious factor contributingto aggression and violence in bars, but the relationshipis not as simple as it might seem. Alcohol contributes toviolence by limiting drinkers’ perceived options during aconflict, heightening their emotionality, increasing theirwillingness to take risks, reducing their fear of sanctions,and impairing their ability to talk their way out oftrouble.10 Many of the alcohol problems police deal withcan be attributed to ordinary drinkers who go on binges,drink more than they usually do, or drink on an emptystomach. In general, those who drink excessively are moreaggressive and also get injured more seriously than thosewho drink moderately or not at all. 11 Moderate drinkers donot appear to be at significantly higher risk of injury thannondrinkers.Culture of DrinkingCultures that are more accepting of intoxication as anexcuse for antisocial or aggressive behavior, and that relaxthe normal rules of society during drinking time, havehigher levels of aggression and violence in and aroundbars.12 This tolerance for intoxication is often reflectedin a society’s laws related to legal defenses to crimes, and

The Problem of Assaults in and Around Barsto the regulation of drinking and the alcohol industry. Insome peer groups, intoxication is an accepted excuse foraggression and violence.13Type of EstablishmentCertain types of bars, such as dance clubs, have higherlevels of reported violence.14 Neighborhood bars andsocial clubs have lower levels of reported violence,partly because patrons know one another well, and partlybecause they usually resolve conflicts privately. Restaurantsthat serve alcohol also have less violence. Bars that serveas pickup places, cater to prostitutes, traffic in drugs orstolen goods, or feature aggressive entertainment are athigher risk for violence.Concentration of BarsThe evidence on the effect of bar concentration is mixed.Some bars attract crime, while others are merely affectedby crime in the surrounding neighborhood. Blocks withbars have higher levels of reported crime than blockswith no bars.15 High concentrations of bars can increasebarhopping, and if all bars close at the same time, therisks of conflicts on the street increase. But the mere factthat a neighborhood has a high concentration of barsdoes not necessarily mean there will be higher crime levelsin the area.16Bar Closing TimeBars’ hours of operation contribute to the risk ofviolence in different ways. When all bars in a given areaclose at the same time, and large numbers of patronsexit simultaneously, crowds may linger on the sidewalk

Assaults in and Around Bars, 2nd Editionto wait for transportation or to order food from latenight restaurants, and competition for these services canprecipitate assaults. Moreover, large groups of patronsfrom incompatible social groups might come together,creating conflict.17Uniform mandatory closing hours also encourage somepatrons to drink heavily just before closing, knowingthey cannot legally buy another drink for the rest of thenight. It is generally the case that bars with later closinghours experience more assaults than those with standardbusiness hours, although additional research on the effectsof later or staggered bar closing times is needed. 18Aggressive BouncersSome security staff see themselves as enforcers, ratherthan as protectors of customers’ safety. 19 The moreaggressively the security staff handles patrons, the moreaggressively patrons respond. Many security employeesand bouncers lack the skills to defuse violence. Thepresence of large, muscular men dressed in black,which is not uncommon for security staff, encouragesconfrontations with some patrons, while discouragingthem with others. Bouncers’ very presence maysubconsciously signal to some patrons that physicalconfrontation is an acceptable way to resolve disputes inthat bar. Bouncers are implicated (whether justifiably soor not) in a significant proportion of assaults. 20 However,victims of aggression by security staff may be hesitant toreport the assault for several reasons: they may not havean accurate description of the bouncer involved, they mayfear retaliation and being banned from the bar, or theymay not want their own actions to be scrutinized. 21

The Problem of Assaults in and Around BarsHigh Proportion of Young Male StrangersThe overwhelming majority of attackers and victimsare young men (18 to 29 years old). Many young mengather and drink alcohol to establish machismo, bondwith one another, and compete for women’s attention. 22Many incidents of bar aggression start when young menchallenge one another.23 This is more likely to happen whenthey do not know each other. Overall, women’s presencehas a calming effect on men’s behavior in crowded bars. 24Price Discounting of DrinksMany bars offer discounted prices for drinks to attractpatrons, but price discounting increases patrons’intoxication levels and thereby increases the risks ofaggression.Continued Service to Drunken PatronsDrinkers report that the most common reaction to theirdrunkenness in bars is continued alcohol service. 25 Inpart, this occurs because staff have difficulty determiningwhether patrons are drunk, particularly when customersobtain drinks from several sources within the bar (e.g.,bartenders, waitresses, and “shot girls”). 26 Determiningwhether patrons are drunk is more difficult in overcrowdedbars, as servers are under pressure to serve customersquickly. In addition, crowded venues are noisy, making itdifficult for servers to hear verbal cues that would suggestdrunkenness.27 Refusing service to drunken patrons oftenmakes them angry. Bartenders and wait staff who donot want this aggression directed at them, and who alsomay not want to risk losing tips, often continue to serveobviously drunken patrons.

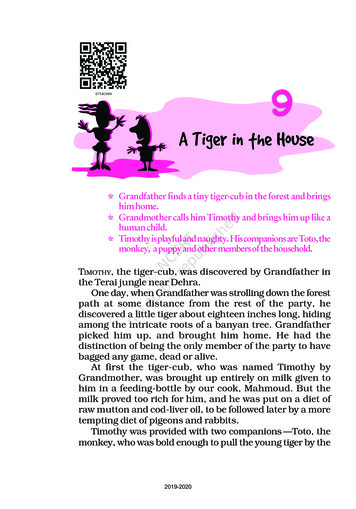

Assaults in and Around Bars, 2nd EditionCrowding and Lack of ComfortPoor ventilation, high noise levels, and lack of seatingmake bars uncomfortable. This discomfort increases therisks of aggression and violence.28 Crowding around thebar, in restrooms, on dance floors, around pool tables, andnear phones creates the risk of accidental bumping andirritation, which can also start fights.29Kip KelloggCrowding in bars creates the risk of accidental bumping andirritation, which can lead to assaults.Competitive SituationsThe high emotions that arise during competition inbars—whether patrons are watching sporting events ontelevision or competing themselves in pool, darts, or othertypical bar games—can turn to anger and frustration. 30Competitive drinking contests (e.g., “chugging” beer orrolling dice for drinks) contribute to excessive drinking.Sports bars may foster a “macho” atmosphere and maycontribute to customers’ sense that aggression is anacceptable part of the social setting. 31 Competition outsidethe bar—for food service, public transportation, walkingspace, women’s attention, and so forth—can similarlytrigger violence.

The Problem of Assaults in and Around Bars Low Ratio of Staff to PatronsInadequate staffing increases the competition for serviceand the frustration of patrons, and reduces opportunitiesfor staff to monitor excessive drinking and aggression.32Lack of Good EntertainmentEntertained crowds are less hostile. Quality music (asdefined by the patrons) is more important than the music’snoise level.33, §Unattractive Décor and Dim LightingRecognizing that attractiveness is highly subjective,obviously unattractive, poorly maintained, and dimly litbars signal to patrons that the owners and managers havesimilarly low standards for behavior, and that they willlikely tolerate aggression and violence. 34Tolerance for Disorderly ConductIf the bar staff tolerates profanity and other disorderlyconduct, it suggests to patrons that the staff will tolerateaggression and violence, as well.35Availability of WeaponsPatrons can use bottles, glasses, pool cues, heavy ashtrays,and bar furniture as weapons. The more available anddangerous these items are, the more likely they will causeserious injury during fights and assaults.§Newspaper articles and reportsfrom some police agencies suggestthat certain forms of music, suchas hip-hop, attract aggressive andviolent crowds, but it is unlikely thatthe musical form itself generatesaggression, at least not directly.

10Assaults in and Around Bars, 2nd EditionLow Levels of Police Enforcement and Regulation§Some police departmentsdiscourage or prohibit uniformedpatrol officers from inspecting bars,while other departments encourageit and make it a key element oftheir efforts to control problemsin and around bars. The CharlotteMecklenburg (North Carolina) PoliceDepartment successfully lobbied forlegislative changes to allow policeofficers to inspect licensed premises.Low levels of liquor-law enforcement and regulationreduce owners’ and managers’ incentives to adoptresponsible practices.§ We do not know for certain whateffect the deployment of off-duty police officers in andaround bars has on assault rates.

Understanding Your Local ProblemUnderstanding Your Local ProblemThe information provided above is only a generalizeddescription of the problem of assaults in and around bars.You must combine the basic facts with a more specificunderstanding of your local problem. Analyzing the localproblem helps in designing a more effective responsestrategy.StakeholdersIn addition to criminal justice agencies, the followinggroups have an interest in the assaults-in-and-around-barsproblem and ought to be considered for the contributionthey might make both to gathering information about theproblem and to responding to it: risk

to analyze the problem, and means to assess the results of a problem-oriented policing project. They are designed to help police decide how best to analyze and address a problem they have already identified. (A companion series of Problem-Solving Tools guides has been produced to aid in various aspects of problem analysis and assessment.)