Transcription

VOL. 94, No. 12ISSN 0042-2983A CULTURAL AND SPIRITUAL M O N T H L Y O F T H E R A M A K R I S H N A O R D E RStarted at the instance of Swami Vivekananda in the year 1895 as Brahmavâdin,it assumed the name The Vedanta Kesari in 1914.For free edition on the Web, please visit: www.sriramakrishnamath.orgDecember 2007Upanishads in Daily LifeVedic PrayerEditorial445Upanishads and We446Articles Peace Chant in Upanishads—Swami SridharanandaSri Ramakrishna:Upanishads Revitalised—Swami AdiswaranandaSri Sarada Devi in the Light of the Upanishads—Pravrajika AtmadevapranaSwami Vivekananda’s Love of Upanishads—Swami GautamanandaDirect Disciples of Sri Ramakrishna:the Living Upanishads—SudeshAn Overview of the Upanishads in the West—Swami TathagatanandaUpanishads and the Science of Yoga—N.V.C. SwamyThe Story of Prajapati and Its Meaning—Swami DayatmanandaSo Began the Story—Prema NandakumarUpanishadic Guidelines for the Practice of Medicine—Swami BrahmeshanandaUpanishads and the Ideal of Service—M. Lakshmi KumariUpanishads—the Basis of All World Religions—Swami AbhiramanandaModern Science and Upanishads—Jay LakhaniThe Bhagavad Gita: Quintessence of the Upanishads—Swami SandarshananandaYouth and the Upanishads—Swami BodhamayanandaSages of the Upanishads—Swami SatyamayanandaThe Upanishads and the Corporate World—S K ChakrabortyUpanishads: the Bedrock of Indian Culture—Pramod 571577583Compilations ‘I Have Never Quoted Anything But the Upanishads’—Swami VivekanandaThe Upanishads and Their Origin—Swami AshokanandaThe Message of the Upanishads—Swami RanganathanandaCall of the Upanishads (Some Practical Guidelines)Vivekananda Tells StoriesThe Power of the UpanishadsUpanishadic Ideas in Popular CultureTen Commandments for Students From Taittiriya Upanishad451456460521543570576588Question & Answer Frequently Asked Questions About Upanishads—Swami HarshanandaMahasamadhi of Swami Gahananandaji Maharaj - p.605488

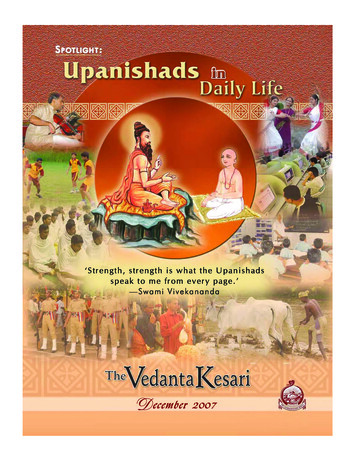

4Cover StoryUpanishads in Daily LifeThough the Upanishads were revealed in a different age, theirpower and influence is ageless and enduring. 'Time' cannot contain or exhaust the perpetuity of the Upanishadic truths. Theirpower and relevance, however, needs reaffirmation and restatement to suit changed and the ever-changing circumstances. This iswhat is conveyed in this issue's cover design. In the midst ofchanged circumstances, represented by pictures of various humanactivities, lie the eternal teachings of the ancient rishis, the discoverers of the Upanishads. The design also tries to convey the factthat Upanishads form the basis of Indian culture. The central message of the Upanishads is conveyed through Swami Vivekananda'swords.Photo Courtesies: T. Srinivas (Mysore), Shankar Basu (Haridwar), Lingaraj G.J.(Bangalore), Krishnan (Chennai) and images from the Internet.Cover design credits: Ravi and Sekar D.The Vedanta Kesari Patrons’ SchemeWe invite our readers to join as patrons of the magazine. They cando so by sending Rs.1500/- or more. Names of the patrons will beannounced in the journal under the Patrons' Scheme and they willreceive the magazine for 20 years. Please send your contribution toThe Manager, The Vedanta Kesari by DD/MO drawn in favour ofSri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai with a note that it is for thePatrons' Scheme.PATRONDONORS Mr. R.S. Pai, Bangalore,M/s. Hare Rama Hare Krishna PrintRs.1000Rs.1000525. Mrs. Hema Malini, Mysore526. N. Narayanan, ChennaiThe Vedanta Kesari Library SchemeSL.NO.NAMES OF SPONSORS3117. A Devotee of Ramakrishna, Bulgaria3118.-do3119.-do3120. Mr. S.T. Muralitharan, Chennai3121.-do3122. Mr. & Mrs. Ch. Narasimha Rao, A.P.AWARDEE INSTITUTIONSD.A.V. Centenary Public School, Mukherjee Nagar, Delhi - 110 009D.A.V. Centenary Public School, Model Town, Delhi - 110 009D.A.V. Centenary Public School, Mandir Narela, Delhi - 110 040Bai Ruttonbai F.D. Pandey Girls High School, Mumbai - 400 008Dr. Mahalingam College of Engineering & Tech., Pollachi - 642 003Rajendran Dharmapuri Foundation School, A.P. - 506 007Continued on page 153

E VOL. 94, No. 12, DECEMBER 2007 ISSN 0042-2983ACH SOUL IS POTENTIALLY DIVINE.T HEGOAL IS TO MANIFEST THE DIVINITY WITHIN.Vedic Prayers mo XodmZm§ à dümoØdü {dœm{Ynmo éÐmo h{f Ÿ&{haÊ J ª ní V Om mZ§ g Zmo wÕçm ew m g§ Zw ºw Ÿ&&May He, who created the gods and supports them; who witnessed thebirth of the cosmic soul; who confers bliss and wisdom on the devoted, destroying their sins and sorrows, and punishing all breaches of law;—may He,the great seer and the lord of all, endow us with good thoughts!—Shvetashvatara Upanishad, IV.12 mo « mU§ {dXYm{V nydª mo d¡ doXm§ü à{hUmo{V Vñ ¡Ÿ&V§ h Xod§ AmË w{ÕàH me§ w jw dw eaU h§ ànÚoŸ&&{ZîH b§ {Z{îH« § emÝV§ {ZadÚ§ {ZaÄOZ ²Ÿ&A Vñ na§ goV§w X½YoÝYZ{ dmZb ²Ÿ&&He who at the beginning of creation projected Brahma (Universal Consciousness), who delivered the Vedas unto him, who constitutes the supremebridge of immortality, who is partless, free from actions, tranquil, faultless,taintless, and resembles the fire that has consumed its fuel,—seeking liberationI go for refuge to that Effulgent One, whose light turns the understandingtowards the Atman.—Shvetashvatara Upanishad, VI.18-19

Upanishads and WeThey and WeThere is a sharp contrast in these twoterms: Upanishads and we, the moderns.Upanishads were composed (strictlyspeaking, ‘revealed’) at least 5000 years ago(though there are differences in opinion aboutthis). ‘We’ live in twenty-first century.The rishis or sages to whom these ‘books’(as the Upanishads are sometimes referred to)were revealed lived in forests, ate simplest offood, meditated for long hours, and had nodistractions such as Internet and multichannel-television. We live in a modern setting,having a sophisticated life-style (despite a largenumber of people living in miserableconditions right under the nose of the morefortunate ones), eat varieties of instantdelicious food, and have made Internet andTV viewing as part of our life.They lived in hermitages or in smallcottages, in tune with nature, with an abundance of trees, creepers, rivers, birds and evenwild animals freely roaming around theirplace. We, on the other hand, live in an age ofurbanization, deforestation, polluted rivers anda dwindling number of bird and animalspecies.The rishis did not have any threats fromterrorists or unscrupulous politicians or blackmarketers. We, the member of modern society,have to be always on guard and have a largenetwork of security and intelligence agenciesto do it.The rishes did not have to travel toparticipate in national or internationalconferences. They were mainly confined toVe d a n t aKe s a r itheir world of contemplation and quietitude.We, on the other hand, have plenty ofopportunities to become busybodies. What tospeak of professionals and officials, even highschool students have many such events toattend to.They and we, rishis and modern men,are therefore placed in radically differentsituations and contexts.Should it mean, (oh, this childishsuggestion!) that the rishis represented aprimitive, yet-to-evolve human beings livingat the dawn of the civilization? And we, themodern ones, represent progress andprosperity? This needs an objective and honestdeliberation.Though rishis and we differ much in ourvisible or palpable life-styles, there is much incommon. Like the great rishis, we too seekthe answer to ultimate questions of life; wetoo want to discover the ultimate purpose oflife and unravel the mystery of creation. Theylonged to know what a human being is in hisor her deepest core; why is a man born andwhy he suffers and where does he go afterdeath. We, too, have been grappling with theseissues in our own ways for centuries, ourmodernity notwithstanding. While we try toanswer these questions by observing ‘life’ withour microscopes or telescopes, the rishis justclosed their eyes, disconnected from the worldof senses and entered into a world not seenby the senses. The rishis seemed to havesucceeded and we are still struggling, rarelywanting to question our instruments andmethods of investigation. All our ‘answers’ are 446 D E C E M B E R2 0 0 7

7temporary presumptions and the rishis throwquiet challenges to contradict their conclusions.So sure are they of what they have understoodof life that the expression ‘There is no otherway’ appears in many Upanishads.Despite our ‘progress and scientificadvancements’ we have not been able to solvethe problems of life. Violence, in various forms,has not been rooted out. Nor has been cruelty,lust, jealousy and meaninglessness of life.Increase in the number of TV channels has inno way solved the problem of boredom. Norhave the signing of a number treaties solvedthe problem of hunger, homelessness andpoverty. We are in need of many moral andspiritual correctives while the rishis were theliving embodiments of moral and spiritualperfection. We differ from the rishis on thesurface; at the deeper level of seeking andwanting to solve the challenge of life anddeath, we share a common heritage. The onlydifference that is apparent is this: while theystand etched in our collective memory as theshining images of moral and spiritualperfection and lived exemplary lives, we, themodern men, are struggling and evolving toreach that state.Another fact about rishis that we mustnot forget is that not all rishis werecontemplatives living in forests. Upanishadsharmonise all contradictions of life. This theydo by making every act of life, apparentlysacred or secular, as an act of worship of theDivine. We, thus, find among the Upanishadicrishis contemplatives, kings, housewives, andeven a cart-puller. Says Swami Vivekananda:‘In various Upanishads we find that this Vedantaphilosophy is not the outcome of meditation inthe forests only, but that the very best parts of itwere thought out and expressed by brains whichwere busiest in the everyday affairs of life. Wecannot conceive any man busier than an absoluteVe d a n t aKe s a r imonarch, a man who is ruling over millions ofpeople, and yet, some of these rulers were deepthinkers.’1Now to sum up this pretendedcomparison between us and the givers of theUpanishads. There is much to learn from thesages of Upanishads. Despite the fact that wehave come a long way from those wonderfultimes to the present state, we are yet to learnour lessons—many of them.Discovering the Eternal Behind the FleetingLet us, however, be clear about one thing:the Upanishads are not old, in the conventionalsense of the term. The word ‘old’ is associatedwith something outdated, worn-out, ineffective, and fit to be discarded. The Upanishads,however, are young with a timeless wisdom.How could something so old as the Upanishads be still effective and youthful, one mightwonder? Suppose you go to a Himalayan riverflowing for centuries. You stand on its banks,bend down and take a handful of its water.What have you done? You have touched anancient river. The water of that river has beenflowing like this for centuries. Though ‘old’, itis ever new. The river is always renewing itself.Though ancient, it is modern at the same time.Nor does the term ‘modern’ have anabsolute meaning. Its meaning keeps changing.A century ago also people called themselvesmodern just as we call ourselves moderntoday. What is modern today will becomeancient or old tomorrow. The wisdom ofUpanishads, however, is eternal. They are abody of ‘eternal values for a changing society’.Certain things, though they become old,never become outdated. Sun and moon arequite, quite old. Just because they are old, theydo not stop dispelling darkness. The same canbe said of the wisdom of the Upanishads.Though ‘old’, it is ever relevant. It is ageless. 447 D E C E M B E R2 0 0 7

8Its enduring value lies in the timeless messageof the divinity and eternity of soul it preaches.The message of the Upanishads is long lastingbecause it deals with certain everlasting truths.They sing, as it were, the song of eternity.The Upanishads are a book of discoveries—most of it about human personality,its structure and uniqueness, and also aboutthe ultimate nature of Godhead and theuniverse we live in. One reads in the Upanishads, a sage lost in intense meditation, comingface to face with the Immortal Core of humanbeings, rising and addressing the wholecreation, as it were,‘Hear, ye children of immortal bliss! Even yethat dwell in higher spheres! For I have foundthat Ancient One who is beyond all darkness,all delusion. And knowing Him, ye also shall besaved from death.’2A Great Spiritual EventThis event, like the discovery of fire andthen of wheel, must have happened in timethough no records are available as to its date,place and the name of the person who firsthad it. (Countless men and women down themillennia have reaffirmed the validity of thatexperience.) What matters is not its historicityor how old it is but the genuineness andindisputable nature of this discovery. What themodern world needs is this Upanishadic ideaof immortality of the soul and the oneness ofexistence.How does this idea of immortality helpus? The simplest value of this idea is that bythinking of this we get a great relief that weare not matter, we are not sinners or ‘bad’.Essentially we are good, nay, divine. All thatwe call evil is not a part of our real Core whomthe Upanishads call as atman. We are deathlessand changeless and are children ofimmortality. Once we get convinced of thisVe d a n t aKe s a r igrand truth, our approach to life becomespositive and affirmative.Besides this, the Upanishads also laymuch emphasis on living a pure life as anatural corollary to realise this idea of atman.The Kathopanishad states:‘One who has not desisted from bad conduct,whose senses are not under control, whose mindis not concentrated, whose mind is not free fromanxiety (about the result of concentration),cannot attain this Self.’3In other words, the ideal of theimmortality of the Self will take roots only if aperson is morally strong and has disciplinedhis senses and mind. If this is not kept in mind,there is a possibility of mistaking the body orego to be the Self and make us pleasure-seekersand arrogant.The Upanishads illustrate this throughthe story of Prajapati’s teachings to Indra, therepresentative of gods, and Virochana, therepresentative of demons. Both Indra andVirochana approached Prajapati requestinghim to impart Self-knowledge to them. Theywere asked to undergo self-control for a setperiod and then both were given the sameteaching: the image you see when you lookinto a mirror, you are That. While Virochana,not yet fully pure and hence less-qualified, gotsatisfied with it, Indra went deeper. Heapproached Prajapati, and after a prolongedperiod of self-discipline and self-purification,finally learnt the Truth his teacher had beentrying to drive home.Likewise, if we seek the truth of atman,we must be patient and persistent, and purifythe mind in order to experience It.The ChallengeThe Upanishads are in no way afraid ofthe new frontiers of objective knowledge, 448 D E C E M B E R2 0 0 7

9which modern day science and technology areopening out. They never felt any contradictionbetween the two. Science of discovery of theSelf (atmavidya) is not opposed to theknowledge of objective world. The knowledgeof physics and chemistry and computers dealswith the perceivable or palpable sensory data.The Upanishads deal with the seer, the Knowerof all activities and objects. Physical Sciencesare quite acceptable in their search for Truthand are welcome to come out with freshtechnology and advancement. But to say thatman’s happiness or fulfilment will emerge outof it is underestimating man’s hunger forhappiness. ‘Man wants the infinite’, says theChandogya Upanishad. The finite cannotsatisfy him. And then comes a surprise. TheUpanishads throw a challenge to the modernworld:‘Only when men shall roll up the sky like a skin,will there be an end to misery for them withoutrealizing God.’4In other words, just as sky, which isformless and intangible, cannot be rolled uplike a piece of paper or sheet of cloth (or animalskin), so also it is vain to claim that man canbecome happy and fulfilled without knowingGod (or the Divine Self within us). Upanishadsdo not mince words in saying that only bySelf-knowledge can a person become trulyhappy in life. No achievement, whetherscientific or secular, can replace it.Restating the Eternal TruthsUpanishads are a mine of Knowledge.But like many other important things in life,we tend to overlook them. One of the reasonsfor this is their language. There is always aneed to restate and rephrase the eternal truthsof the Upanishads. India has had a glorioushistory of many great spiritual giants like SriVe d a n t aKe s a r iShankaracharya and the likes, who tried todraw our attention to the eternal relevance ofthe message of Upanishads. They had to restatethe message in a language which the peoplecould understand. In our own times, we havethe similar effort being made in the life andteachings of Swami Vivekananda and SriRamakrishna. Swamiji said that he ‘neverquoted anything except the Upanishads’. Allhis teachings are a contemporary restatementof the eternal Upanishadic truths. Take forexample Swamiji’s well-known statement thateach soul is potentially divine. Though apowerful statement, it is not new. In theChandogya Upanishad, the rishi UddalakaAruni tells his son Shvetaketu, ‘You are That.’By the word ‘That’, the sage Uddalaka meantDivinity or atman. So, the meaning is, ‘Youare atman.’ Now look at Swamiji’s words:‘Each soul is potentially divine’. They implythe same thing in a much more appealing way.Though atman, we are not aware of it. Thisignorance makes the truth of atman unsure or‘potential’. This adds a whiff of freshness andoriginality to it.Paying tributes to Swami Vivekananda’scontribution to the restatement of the Upanishads in the modern idiom, Sister Niveditasays,‘The truths he [Swami Vivekananda] preacheswould have been as true, had he never beenborn. Nay more, they would have been equallyauthentic. The difference would have lain in theirdifficulty of access, in their want of modernclearness and incisiveness of statement, and theirloss of mutual coherence and unity.’5Swamiji made Upanishads available toall. Before Swamiji came to scene, the study ofUpanishads was restricted and reserved toonly a section of people. Not everyone wassupposed to read them. But by restating themin modern idiom, Swamiji made them 449 D E C E M B E R2 0 0 7

10available to all. Not only that he restated them,he also gave, through reinterpreting them,befitting answers to numerous knottyproblems modern man faces. He felt theproblem of increasing violence and religiousintolerance, for instance, can only be solvedby adopting the Upanishadic view that all menand women are divine and each one is at onestage of evolution in perceiving this inherentdivinity. He said,‘Man is not travelling from error to truth, butclimbing up from truth to truth, from truth thatis lower to truth that is higher.’6This idea of solidarity of existence is alsothe real basis for love and service. To loveothers, in fact, is to love one-Self.How to make the teachings of theUpanishads practical? Indeed Swamiji believedthis to be the mission of his life. He said:‘The dry Advaita must become living—poetic—in everyday life; out of hopelessly intricatemythology must come concrete moral forms; andout of bewildering Yogi-ism must come the mostscientific and practical psychology—and all thismust be put in a form that a child may grasp it.That is my life’s work.’7In ConclusionStrength and fearlessness is what theUpanishads preach. Strength comes from thatwhich is enduring. And fearlessness comesfrom knowing our indestructible and immortalnature. When Janaka, the celebrated kingmentioned in the Upanishads, ‘realised’ thetruth of atman, it was said that he becamefearless. Swamiji held the Upanishads as atreasure house of strength and fearlessness.Here, again, he restated the ancient truths inthe modern idiom:‘This is the one question I put to every man. . .Are you strong? Do you feel strength?—for Iknow it is truth alone that gives strength.’8Upanishads are the very basis of Indianculture and spiritual heritage. No one can everunderstand or appreciate the essence of Indianculture without making a study of theUpanishads. They are like the forefathers ofthe Indian culture and civilisation. All Hindubeliefs, rituals and festivals, all systems oforthodox philosophical systems in India andalso the lives and teachings of all the mysticsand saints India has seen over the centuriesare rooted in the mystic realisations ofUpanishadic rishis.This year’s spotlight issue focuses onhow and why the message of Upanishads isapplicable to life in today’s context. Variousaspects of this subject have been explored. Theapproach is to relate the Upanishads to lifeand not just leave it to dry academicdiscussions. Eminent monastic and lay writershave contributed thoughtful articles. Ourthanks to each one of them. We hope ourreaders will find this volume useful in theirjourney to appreciate the pressing need tomake the message of the Upanishads practical.We wish all our readers, in the language ofthe Upanishads, ‘Godspeed you in yourjourney beyond the darkness of ignorance,(svasti vah paraya tamasah parastat!). References1. CW, 2: 2935. CW, 1: xiv2. Shvetashvatra, 3.86. CW, 1:xiiVe d a n t a3. Kathopanishad, I.ii.247. CW, 5: 104-105Ke s a r i 450 D E C E M B E R4. Shvetashvatara, 6.208. CW, 2:2012 0 0 7

‘I Have Never Quoted AnythingBut the Upanishads’SWAMI VIVEKANANDAThe Message of StrengthStrength, strength is what theUpanishads speak to me from every page. Thisis the one great thing to remember, it has beenthe one great lesson I have been taught in mylife; strength, it says, strength, O man, be notweak. Are there no human weaknesses?—saysman. There are, say the Upanishads, but willmore weakness heal them, would you try towash dirt with dirt? Will sin cure sin, weaknesscure weakness? Strength, O man, strength, saythe Upanishads, stand up and be strong. Ay,it is the only literature in the world whereyou find the word ‘Abhih’, ‘fearless’, usedagain and again; in no other scripture in theworld is this adjective applied either to Godor to man.1And the more I read the Upanishads, myfriends, my countrymen, the more I weep foryou, for therein is the great practicalapplication. Strength, strength for us. What weneed is strength, but who will give us strength?There are thousands to weaken us, and ofstories we have had enough. Every one of ourPuranas, if you press it, gives out storiesenough to fill three-fourths of the libraries ofthe world. Everything that can weaken us as arace we have had for the last thousand years.It seems as if during that period the nationallife had this one end in view, viz., how tomake us weaker and weaker till we havebecome real earthworms, crawling at the feetof every one who dares to put his foot on us.Therefore, my friends, as one of your blood,Ve d a n t aKe s a r ias one that lives and dies with you, let me tellyou that we want strength, strength, andevery time strength.And the Upanishadsare the great mineof strength. Thereinlies strength enough to invigoratethe whole world;the whole worldcan be vivified,made strong, energised throught h e m .They willcall withtrumpetvoice uponthe weak, themiserable, and thedowntrodden of all races, all creeds,and all sects to stand on their feet and befree. Freedom, physical freedom, mentalfreedom, and spiritual freedom are thewatchwords of the Upanishads.2For centuries we have been stuffed withthe mysterious; the result is that ourintellectual and spiritual digestion is almosthopelessly impaired, and the race has beendragged down to the depths of hopelessimbecility—never before or since experiencedby any other civilised community. There mustbe freshness and vigour of thought behind tomake a virile race. More than enough to 451 D E C E M B E R2 0 0 7

12strengthen the whole world exists in theUpanishads. The Advaita is the eternal mineof strength. But it requires to be applied.3Ay, this is the one scripture in the world,of all others, that does not talk of salvation,but of freedom. Be free from the bonds ofnature, be free from weakness! And it showsto you that you have this freedom already inyou. . .4What makes a man stand up and work?Strength. Strength is goodness, weakness issin. If there is one word that you find comingout like a bomb from the Upanishads, burstinglike a bomb-shell upon masses of ignorance, itis the word fearlessness. And the only religionthat ought to be taught is the religion offearlessness. Either in this world or in theworld of religion, it is true that fear is the surecause of degradation and sin. It is fear thatbrings misery, fear that brings death, fear thatbreeds evil.And what causes fear? Ignorance of ourown nature. Each of us is heir-apparent to theEmperor of emperors; we are of the substanceof God Himself. Nay, according to the Advaita,we are God Himself though we have forgottenour own nature in thinking of ourselves aslittle men.5We speak of many things parrot-like, butnever do them; speaking and not doing hasbecome a habit with us. What is the cause ofthat? Physical weakness. This sort of weakbrain is not able to do anything; we muststrengthen it. First of all, our young men mustbe strong. Religion will come afterwards. Bestrong, my young friends; that is my advice toyou. You will be nearer to Heaven throughfootball than through the study of the Gita. . .You will understand the Upanishads betterand the glory of the Atman when your bodystands firm upon your feet, and you feelyourselves as men.6Ve d a n t aKe s a r iThe Ideal of FreedomWhether you are an Advaitist or adualist, whether you are a believer in thesystem of Yoga or a believer in Shankaracharya, whether you are a follower of Vyasaor Vishvamitra, it does not matter much. Butthe thing is that on this point Indian thoughtdiffers from that of all the rest of the world.Let us remember for a moment that, whereasin every other religion and in every othercountry, the power of the soul is entirelyignored—the soul is thought of as almostpowerless, weak, and inert—we in Indiaconsider the soul to be eternal and hold that itwill remain perfect through all eternity. Weshould always bear in mind the teachings ofthe Upanishads.7It was given to me to live with a man[Sri Ramakrishna] who was as ardent a dualist,as ardent an Advaitist, as ardent a Bhakta, asa Jnani. And living with this man first put itinto my head to understand the Upanishadsand the texts of the scriptures from anindependent and better basis than by blindlyfollowing the commentators; and in myopinion and in my researches, I came to theconclusion that these texts are not at allcontradictory. So we need have no fear of texttorturing at all! . . . Therefore I now find in thelight of this man’s life that the dualist and theAdvaitist need not fight each other. Each hasa place, and a great place in the national life.Therefore any attempt to torture the texts ofthe Upanishads appears to me very ridiculous.8Let me draw your attention to one thingwhich unfortunately we always forget: thatis—‘O man, have faith in yourself.’ That is theway by which we can have faith in God.9Learning to Solve the Mystery of LifeOur Upanishads say that the cause of allmisery is ignorance; and that is perfectly true 452 D E C E M B E R2 0 0 7

13when applied to every state of life, either socialor spiritual. It is ignorance that makes us hateeach other, it is through ignorance that we donot know and do not love each other. As soonas we come to know each other, love comes,must come, for are we not one? Thus we findsolidarity coming in spite of itself.Even in politics and sociology, problemsthat were only national twenty years ago canno more be solved on national grounds only.They are assuming huge proportions, giganticshapes. They can only be solved when lookedat in the broader light of international grounds.International organisations, internationalcombinations, international laws are the cryof the day. That shows the solidarity. Inscience, every day they are coming to a similarbroad view of matter. You speak of matter,the whole universe as one mass, one ocean ofmatter, in which you and I, the sun and themoon, and everything else are but the namesof different little whirlpools and nothing more.Mentally speaking, it is one universal oceanof thought in which you and I are similar littlewhirlpools; and as spirit it moveth not, itchangeth not. It is the One Unchangeable,Unbroken, Homogeneous Atman. The cry formorality is coming also, and that is to be foundin our books. The explanation of morality, thefountain of ethics, that also the world wants;and that it will get here.10The Upanishads told 5,000 years ago thatthe realisation of God could never be hadthrough the senses. So far, modern agnosticismagrees, but the Vedas go further than thenegative side and assert in the plainest termsthat man can and does transcend this sensebound, frozen universe. He can, as it were, finda hole in the ice, through which he can passand reach the whole ocean of life. Only by sotranscending the world of sense, can he reachhis true Self and realise what he really is.11Ve d a n t aKe s a r iThe Upanishads say, renounce. That isthe test of everything. Renounce everything.It is the creative faculty that brings us into allthis entanglement. The mind is in its ownnature when it is calm. The moment you cancalm it, that [very] moment you will know thetruth. What is it that is whirling the mind?Imagination, creative activity. Stop creationand you know the truth. All power of creationmust stop, and then you know the truth atonce.12Here I can only lay before you what theVedanta seeks to teach, and that is thedeification of the world. The Vedanta does notin reality denounce the world. The

The Upanishads and the Corporate World—S K Chakraborty 577 Upanishads: the Bedrock of Indian Culture—Pramod Kumar 583 Compilations 'I Have Never Quoted Anything But the Upanishads'—Swami Vivekananda 451 The Upanishads and Their Origin—Swami Ashokananda 456 The Message of the Upanishads—Swami Ranganathananda 460