Transcription

The U.S. Army Campaigns of the Civil WarTheGettysburgCamp ignJune – July 1863

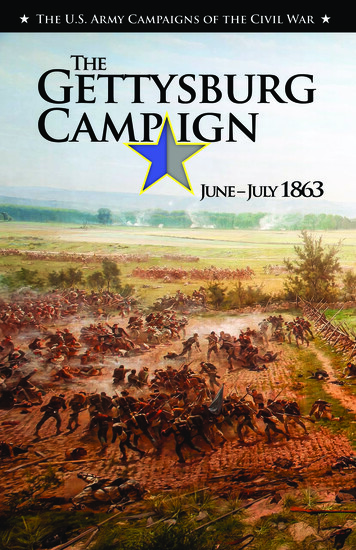

Cover: Scene from the Gettysburg Cyclorama painting, The Battle of Gettysburg, byPaul Phillippoteaux, depicting Pickett’s Charge and fighting at the Angle.Photograph Bill Dowling, Dowling Photography.CMH Pub 75–10

TheGettysburgCamp ignJune – July 1863byCarol ReardonandTom VosslerCenter of Military HistoryUnited States ArmyWashington, D.C., 2013

IntroductionAlthough over one hundred fifty years have passed since thestart of the American Civil War, that titanic conflict continues tomatter. The forces unleashed by that war were immensely destructive because of the significant issues involved: the existence ofthe Union, the end of slavery, and the very future of the nation.The war remains our most contentious, and our bloodiest, withover six hundred thousand killed in the course of the four-yearstruggle.Most civil wars do not spring up overnight, and the AmericanCivil War was no exception. The seeds of the conflict were sownin the earliest days of the republic’s founding, primarily over theexistence of slavery and the slave trade. Although no conflict canbegin without the conscious decisions of those engaged in thedebates at that moment, in the end, there was simply no way topaper over the division of the country into two camps: one thatwas dominated by slavery and the other that sought first to limitits spread and then to abolish it. Our nation was indeed “half slaveand half free,” and that could not stand.Regardless of the factors tearing the nation asunder, thesoldiers on each side of the struggle went to war for personalreasons: looking for adventure, being caught up in the passionsand emotions of their peers, believing in the Union, favoringstates’ rights, or even justifying the simple schoolyard dynamicof being convinced that they were “worth” three of the soldierson the other side. Nor can we overlook the factor that some wentto war to prove their manhood. This has been, and continuesto be, a key dynamic in understanding combat and the profession of arms. Soldiers join for many reasons but often stay in thefight because of their comrades and because they do not want toseem like cowards. Sometimes issues of national impact shrinkto nothing in the intensely personal world of cannon shell andminié ball.5

Whatever the reasons, the struggle was long and costly andonly culminated with the conquest of the rebellious Confederacy,the preservation of the Union, and the end of slavery. Thesecampaign pamphlets on the American Civil War, prepared incommemoration of our national sacrifices, seek to rememberthat war and honor those in the United States Army who died topreserve the Union and free the slaves as well as to tell the story ofthose American soldiers who fought for the Confederacy despitethe inherently flawed nature of their cause. The Civil War was ourgreatest struggle and continues to deserve our deep study andcontemplation.RICHARD W. STEWARTChief Historian6

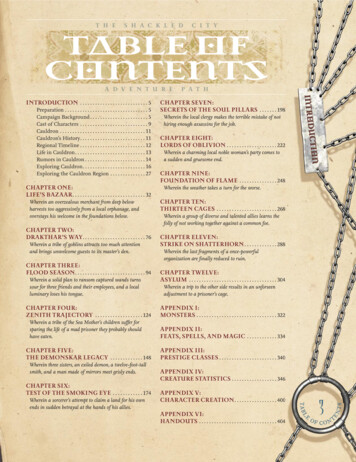

The Gettysburg CampaignJune–July 1863Strategic SettingAfter the Confederates’ victory at Chancellorsville in May1863, General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and theArmy of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker,once again confronted each other across the RappahannockRiver near Fredericksburg, Virginia. The battle, which costHooker nearly 16,000 casualties and Lee some 12,300 losses,had proved indecisive. The two armies maintained an uneasystalemate, occupying virtually the same ground they had heldsince December 1862. Washington, D.C., the U.S. capital, stoodfifty-three miles to the north, while Richmond, Virginia, theConfederate capital, lay fifty-seven miles to the south. The rivalpresidents, Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis, ponderedtheir next moves.Despite the defeat at Chancellorsville and mountingdiscontent on the Northern home front, Lincoln could takeheart from recent developments in the west. In April 1863, Maj.Gen. Ulysses S. Grant shifted 20,000 Union troops from the westbank of the Mississippi River to the east bank, about thirty-fivemiles below the Confederate garrison at Vicksburg, Mississippi.From 1 to 17 May, Grant’s command defeated Confederate forcesat Port Gibson, Raymond, Jackson, Champion Hill, and the BigBlack River Bridge. By the end of the month, Grant had trappedLt. Gen. John C. Pemberton’s 30,000 Confederates inside theirfortifications around Vicksburg. After two unsuccessful frontal7

assaults, Grant’s army settledinto a siege; meanwhile, aConfederate relief force underGeneral Joseph E. Johnsonfailed to rescue Pemberton.Davis confronted a moredaunting set of problemsthan his Northern counterpart. Amid bad news fromVicksburg and other parts ofthe Confederacy, he summonedLee to Richmond twice inmid-May to discuss their strategic options. Despite Lee’svictory at Chancellorsville, themilitary situation in Virginiaappeared to be deteriorating. Inthe Tidewater region, a Federalgarrison of some 20,000 menheld Suffolk, and their presencethreatened both Norfolk andHampton Roads. Given thesize and location of the Federalforce, Davis and Lee also fearedfor the safety of Richmond.On 16 February 1863, Leehad ordered the infantry divisions of Maj. Gens. John BellHood and Lafayette McLawsto march from the army’swinter camp at Fredericksburgto Richmond and HanoverJunction. Two days later,Lee ordered Lt. Gen. JamesLongstreet to take commandof “the Suffolk Expedition,” ashe called it. On 21 March, Leeadvised Longstreet to remainalert for “an opportunity ofdealing a damaging blow, or ofdriving [the enemy] from any8General Longstreet by Alfred R.Waud (Library of Congress)General Lee (Library of Congress)

important positions.” Should Longstreet find such an opening, Leeurged him not to “be idle, but act promptly.”Bad news on nearly all military fronts—above all, the reportthat Grant had trapped Pemberton’s army inside Vicksburg’sdefenses—forced the Davis administration to consider a widerange of options. No single course of action could resolve all thechallenges facing the president. In addition to Vicksburg andSuffolk, Davis also had to consider impending Union offensives inmiddle Tennessee and at Charleston, South Carolina.Lee had, in fact, already crafted a plan for his own army. Inearly April, he advised Confederate Secretary of War James A.Seddon: “Should General Hooker’s army assume the defensive,the readiest method of relieving pressure on [Vicksburg andCharleston] would be for this army to cross into Maryland.” Oneweek later, Lee suggested to Davis:I think it all important that we should assume the aggressive bythe first of May when we may expect General Hooker’s army to beweakened by the expiration of the term of service of many of hisregiments. . . . I believe greater relief would in this way be affordedto the armies in middle Tennessee and on the [South] Carolinacoast than by any other method.During his mid-May deliberations with Davis and Seddon,Lee continued to advocate an offensive operation against Hooker’sarmy. He hoped to take the Army of Northern Virginia north of thePotomac once again. Lee’s reverse at Antietam in September 1862did not deter him from making a second northern expedition.While in winter camp in February 1863, Lee had directed JedediahHotchkiss (then Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s chiefengineer) to draw up a map of the valley of Virginia “extending toHarrisburg, PA and then on to Philadelphia—wishing the preparation to be kept a profound secret.”Not everyone who participated in the strategic conference inRichmond agreed with Lee’s plan. A number of senior Confederateofficials—including Postmaster General John H. Reagan and,for a time, even Davis himself—advocated sending all or part ofLee’s army to Mississippi. In the end, however, Lee’s views wonout. Davis gave his approval for the Army of Northern Virginia’sinvasion of the North. Only one question remained: When shouldthe campaign begin?9

OperationsThe Advance into PennsylvaniaLee issued his initial orders for the northern offensive on3 June, stealthily breaking contact with Hooker’s Army of thePotomac near Fredericksburg to concentrate around Culpeper.Despite Lee’s best efforts, Hooker discovered that the Confederateswere marching northward on 5 June. Hooker sent a force of 7,000cavalry and 4,000 infantry and artillery under his new cavalrycommander, Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, in pursuit of theConfederates. Early on the morning of 9 June, Pleasonton surprisedMaj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart’s Confederate horsemen at Brandy Station.In a chaotic fight that proved to be one of the largest mountedclashes of the war, the Union troopers initially scattered Stuart’smen and nearly captured the vaunted cavalry commander himself.In the end, Stuart held his ground, but it had been a near thing.Richmond newspapers sharply criticized him and demanded thathe redeem himself throughheroic action.General Stuart (Library of Congress)The scare at BrandyStation did not deter Lee inthe least. He forged ahead withambitious plans that wouldtest his army’s new organizational structure in active fieldoperations. After the death ofGeneral Jackson on 10 May,Lee had reconfigured his armyof two corps under Jacksonand Longstreet into threecorps. Longstreet retainedcommand of the First Corps,while two newly promotedlieutenant generals, RichardS. Ewell and Ambrose PowellHill, led the Second and ThirdCorps respectively. The inclusion of Stuart’s cavalry raisedLee’s total strength to roughly75,000 officers and enlistedmen. An unbroken string of10

victories during Lee’s thirteen months in command—assumingthat Antietam was a tactical draw—inspired high morale amongthe rank and file and great confidence in the commander. As oneGeorgian said while passing the general during the march north,“Boys, there are ten thousand men sitting on that one horse.”Lee planned his northward route with care. (See Map 1.) Afterconcentrating at Culpeper, he intended to clear the ShenandoahValley of Union troops and then continue north into Pennsylvania’srich Cumberland Valley. If he stayed west of the Blue RidgeMountains, the range would shield both his army’s supply trainsand, in time, southbound wagons filled with goods taken north ofthe Potomac. On 10 June, Lee ordered Ewell to proceed into theShenandoah Valley. Lee chose Ewell’s Second Corps to lead theGeneral Ewell (Library of Congress)General Hill (Library of Congress)11

advance into Pennsylvania because that command contained mostof the veterans of Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign—men whoknew the region they were marching into.The fight at Brandy Station, meanwhile, convinced Hooker toreconsider his options. When it became apparent that Lee’s entirearmy was heading north, Hooker recommended marching southand attacking Richmond instead. President Lincoln, however,reminded him that “Lee’s army and not Richmond, is your sureobjective point.” On 13 June, Hooker ordered the Army of thePotomac to begin its pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia.Consisting of seven infantrycorps and one cavalry corps, theArmy of the Potomac numberedGeneral Hooker (Library ofCongress)about 94,000 effectives. WhileHooker saw no need for thekind of massive reorganizationthat Lee had recently undertaken, he knew that several ofhis corps contained only twodivisions rather than the usualthree and that he had just lostthousands of veteran soldierswho mustered out when theirtwo-year enlistments expired.For those reasons and more,Hooker believed that Leeoutnumbered him, and he oftenbadgered the general in chief ofthe U.S. Army, Maj. Gen. HenryW. Halleck, either for reinforcements or for authority overgarrisons not currently underhis control.On 14 June, Ewell passedhis first test as corps commanderat Winchester soundly defeatingUnion Brig. Gen. Robert H.Milroy’s garrison. “So impetuouswas the charge of our men that ina few minutes they were over thebreastworks, driving the enemy12

bersburgumbCashtownGettysburgGreencastleCHanoverP E N N S Y L V A N I AM A R Y L A N DEmmitsburgHagerstownWilliamsportFalling TVRG IRGININIAIABaltimoreHarper’sFerryl leyVIaStephenson’s ehSFront RoyalAldieMiddleburgWashingtonManasas JunctionWarrentonM O V E M E N T TO G E T T Y S B U R G3 June–1 July 1863CulpeperCourt HouseUnion ForcesBrandy StationConfederate InfantryConfederate CavalrySkirmishFredericksburg300Orange Court HouseMap 1Miles

out in great haste and confusion,” described a Louisiana captain.Ewell captured 23 cannon, 300 wagons, and 4,000 prisoners. He thensent Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins’ cavalry brigade scouting aheadof the main column. Jenkins’ horsemen rode into Chambersburg,Pennsylvania, on 20 June, and two days later, Ewell’s infantry enteredthe Keystone State near Greencastle.For the next week, Ewell’s troops scoured south-centralPennsylvania for supplies, advancing as far north as the outskirtsof Harrisburg, the state capital. On 21 June, Lee issued GeneralOrders 72, setting forth proper foraging procedures: quartermaster,commissary, ordnance, and medical officers were to obtain neededgoods at fair market value, and all soldiers must respect privateproperty. Jenkins’ cavalry apparently interpreted the order quiteloosely. “Some people, with . . . antiquated ideas of business, mightcall it stealing to take goods and pay for them in bogus money,”wrote a Chambersburg journalist, “but Jenkins calls it business,and for the time being what Jenkins called business, was business.”When Ewell’s infantry arrived, they also enjoyed the bounty ofthe region. Pvt. Gordon Bradwell of the 31st Georgia recalled anissue of “two hindquarters of very fine beef, a barrel or two of flour,some buckets of wine, sugar, clothing, shoes, etc. All this for abouttwenty men.”Reports of such excesses troubled Lee. On 27 June, he issuedGeneral Orders 73 chastising his soldiers for their “instances offorgetfulness” and reminding them of the “duties expected of usby civility and Christianity.” Still, even before Lee’s entire armyhad crossed into Pennsylvania, wagon trains loaded with foodstuffs and other goods began heading south. In addition, reportedthe Chambersburg editor, “Quite a number of negroes, free andslave—men, women and children—were captured by Jenkins andstarted south to be sold into bondage.”Pennsylvanians responded to the arrival of Lee’s army invarious ways. Many civilians in Lee’s path simply fled with all theycould carry. Some Pennsylvania Democrats believed—wrongly,as it turned out—that their political affiliation would protectthem from depredation. A Harrisburg editor opined that Lee’smen enjoyed great success as foragers because “the people of theState were not prepared to meet any foe, and least of all, such afoe as marches beneath the black flag of treason.” He cited thelegislature’s recent failure to improve the state’s militia systemfor leaving south-central Pennsylvania open to invasion. On 914

June, the Lincoln administration had established the Departmentof the Susquehanna to organize local defense, and GovernorAndrew G. Curtin had called out the state’s emergency forces, butall such efforts proved futile. On 26 June, the 26th PennsylvaniaEmergency Regiment deployed against some of Ewell’s men justwest of Gettysburg; those who did not become prisoners scatteredin panic after exchanging a few shots with the Confederates.Even as Ewell neared Harrisburg, he faced only minimal resistance; however, the rest of Lee’s army faced far stiffer oppositionduring its northward advance. Now alerted to Lee’s movements,Hooker sent his cavalry and some infantry to probe the Blue Ridgegaps, seeking opportunities to intercept the Confederate columns.Lee had kept Longstreet’s First Corps and Stuart’s cavalry eastof the Blue Ridge to block Hooker’s advance, resulting in sharpclashes between rival horsemen at Aldie on 17 June, at Middleburgon 19 June, and at Upperville on 21 June. On 23 June, Lee orderedStuart to “harass and impede as much as possible” the progressof Hooker’s army if it attempted to cross the Potomac, and,should that occur, to “take position on the right of our columnas it advanced.” Stuart certainly bothered the Union army andcaused great consternation in Washington, but he chose a northbound course that placed Hooker’s hard-marching army squarelybetween him and Lee for one crucial week in late June. Lee thushad to conduct operations without benefit of the excellent intelligence that Stuart usually provided him.Even so, Lee continued to display an aggressiveness thatconfounded Hooker. Still convinced that he faced “an enemy in myfront of more than my number,” Hooker delivered an ultimatum toHalleck on 27 June—either send reinforcements or relieve him ofcommand. Hooker’s superiors decided to replace him. In a letter tohis wife, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade noted that he was awakenedbefore dawn on 28 June “by an officer from Washington.” Theofficer, Meade wrote, said that “he had come to give me trouble.At first I thought that it was either to relieve or arrest me, andpromptly replied to him, that my conscience was clear. . . . He thenhanded me a communication to read; which I found was an orderrelieving Hooker from the command and assigning me to it.”Hooker was in such a hurry to leave that he failed to provideMeade with a detailed assessment of the military situation. Thenew commander therefore knew little about his own army’s statusand even less about Lee’s. With a hostile army on the march ahead15

of him, his own army in hot pursuit, and a myriad of administrative and operational challenges confronting him, Meade hadto assume the responsibilities of high command in short order.He began by making a few essential administrative and organizational changes and then communicated with General Halleckand President Lincoln in Washington. Meade also fieldednumerous requests for information or supplies from politicaland military officials, and began to develop a plan of action forhis new command based on Halleck’s instructions: “You will . . .maneuver and fight in such a manner as to cover the capital andalso Baltimore. . . . Should General Lee move upon either of theseplaces, it is expected that you will either anticipate him or arrivewith him so as to give him battle.”Despite the defensivetone of Halleck’s instructions,General Meade (Library ofMeade understood that he hadCongress)“to find and fight the enemy,”and he ordered the Army of thePotomac to resume its northward advance the next day,29 June. On 30 June, Meadewas still uncertain as to Lee’slocation and intentions, so hedrafted a contingency plan toconcentrate his army alongPipe Creek in Maryland, justsouth of the Pennsylvaniastate line. Meade’s critics latercited the Pipe Creek circularas proof of his unwillingnessto fight, but his concludingsentence suggested otherwise:“Developments may causethe Commanding General toassume the offensive from hispresent positions.”While encamped nearChambersburg, Lee learned ofMeade’s accession to commandthe day after his appointment.Although he assumed that a16

new commander would enter his duties cautiously, Lee issuedorders on 29 June for the Army of Northern Virginia to concentrateat Cashtown, east of the Blue Ridge and seven miles northwest ofGettysburg. He warned his corps commanders not to give battlewith Meade’s approaching forces until the whole of the army wasconcentrated to provide ready support. By 30 June, most of Hill’sThird Corps had already reached Cashtown. Longstreet remainedwest of the Blue Ridge, but was less than a day’s march away. Ewellmade plans to leave his camps around Carlisle early on 1 July andhead for Cashtown.On 30 June, Hill sent forward a brigade from Maj. Gen.Henry Heth’s division to reconnoiter toward Gettysburg. Thebrigade commander, Brig. Gen.James J. Pettigrew, reportedthat Union cavalry had enteredGeneral Buford (Library ofCongress)the town from the south.Pettigrew had encounteredthe lead element of the Armyof the Potomac—Brig. Gen.John Buford’s cavalry division,which then consisted of twosmall brigades and one six-gunbattery. An outstanding cavalryofficer, Buford had deployed hiscommand to cover Gettysburg’sroad network from the HanoverRoad to the east through theYork Pike and the HarrisburgRoad to the northeast, theCarlisle Road to the north,the Mummasburg Road andChambersburg Pike to thenorthwest, and the FairfieldRoad to the southwest (Map 2).Buford remained uncertain ofLee’s location and intentions, yethe sensed that the Confederateswho had appeared west of townearlier that day would returnthe next morning in far greaternumbers. He was right.17

SBURGROADPIKHACARLISLE ROADRidgeBEREMcPherson’sAMRRg eR i dCHSTOWNADTERROHUNRGDBUO a ADEOVER ROADB e n n e r ’sHillGE T T YSB U R GRockCrR id geeekC u l p ’sHillADROKERGIEPBUORTSIMMILTEMBADWN ROAg eR i dTA N E Y T OC em e t e r yS em in ar yCemeteryHillLittleR o u n d To pG E T T Y S B U R G B AT T L E F I E L D1–3 July 1863R o u n d To p01000YardsMap 22000

The First Day of Battle, 1 JulyAs Buford had expected, Hill ordered Heth’s entire division toadvance on Gettysburg at first light. About 0700, troopers from the8th Illinois Cavalry, posted three miles west of Gettysburg on theChambersburg Pike, spotted shadowy figures nearing the MarshCreek Bridge to their front. According to tradition, Lt. MarcellusJones borrowed a sergeant’s carbine and fired the first shot of theBattle of Gettysburg. He then fired several more rounds at skirmishers from Brig. Gen. James J. Archer’s brigade, the lead elementof Heth’s division. Jones immediately reported the contact; inshort order, Buford learned not only of the mounting threat alongthe Chambersburg Pike but also of enemy activity along roadsto the west and north of Gettysburg. He immediately sent briefbut informative assessments of the rapidly changing situation toMeade at Army headquarters and to Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds,whose I Corps had encamped the previous night just a few milessouth of Gettysburg. In order to keep the Gettysburg crossroadsunder Union control, Buford would need Reynolds’ help. WithHeth’s division in the lead and Maj. Gen. William Dorsey Pender’sdivision close behind, a force of nearly 14,000 Confederates fromGeneral Hill’s Third Corps advanced down the ChambersburgPike toward Buford’s 2,800 cavalrymen.Fortune favored Buford that muggy July morning. Withoutcavalry to scout ahead, Heth admitted, “I was ignorant what forcewas at or near Gettysburg.” This meant that even the slightest resistance from Buford’s pickets compelled Archer’s brigade to halt,deploy skirmishers, and proceed cautiously as if the commandfaced a comparable force of infantry. As Capt. Amasa Dana ofthe 8th Illinois Cavalry recalled, “the firing was rapid from ourcarbines, and . . . induced the belief of four times our number ofmen actually present.” For nearly a mile-and-a-half, each timeArcher’s skirmishers came too close “we retired and continuedto take new position, and usually held out as long as we couldwithout imminent risk of capture.” Buford’s cavalrymen thustraded space for the time required for Reynolds to arrive with hisI Corps. About 1000, Archer’s brigade halted on Herr’s Ridge, twomiles west of Gettysburg, to await the rest of Heth’s division whileBuford’s troopers took up their final defensive line on the next riseto the east—McPherson’s Ridge—one mile closer to town.Reynolds had not yet arrived when Heth launched his strongest attack yet. Deploying Brig. Gen. Joseph R. Davis’ brigade19

north of the Chambersburg Pike and Archer’s brigade south ofit, Heth sent his troops across Willoughby Run and up the slopesof McPherson’s Ridge against Buford’s line. Thanks to the ease ofreloading their single-shot, breech-loading carbines, the cavalrymen produced a volume of fire entirely disproportionate to theirnumbers, but both sides knew the outnumbered troopers couldnot withstand the Confederate infantry much longer. At roughly1015, however, the rattle of drums signaled the arrival of GeneralReynolds and the lead division of the I Corps.The fighting on 1 July west of Gettysburg breaks down intofour phases. The advance of Archer’s Confederate infantry againstBuford’s Union cavalry that began at 0700 and culminated withthe assault on McPherson’s Ridge around 1015 constituted thefirst phase. No officer in either army more senior than a divisioncommander played a major role in this action and casualtiesremained comparatively light. The three remaining phases of the1 July fight featured far more lethal action between large infantryunits, well supported by artillery, with corps commanders and, intime, Lee himself present on the battlefield to make key decisions.Phase two of the 1 July fight, lasting from about 1030until 1200, included two largely independent brigade-levelinfantry actions on McPherson’s Ridge, one on each side of theChambersburg Pike (Map 3). North of the road, Heth sent Davisback into the fight, this time against Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler’sinfantry brigade rather than Buford’s cavalry. Davis turned Cutler’sright flank, but the 380-man 147th New York failed to receive theorder to withdraw and remained in position to protect an artillerybattery. The New Yorkers were hard-pressed by enemy troops intheir front, and their right flank was exposed or “in the air.” Toconfront both threats, the 147th New York refused—or bent back—its rightmost companies, giving the battery time to withdraw. Asthe New Yorkers’ ranks melted away in the crossfire that engulfedthem, Maj. George Harney issued a unique command: “In retreat,double time, run.” During the short but sharp fight, the 147th NewYork lost almost 80 percent of its troop strength.At roughly the same time south of the Chambersburg Pike,Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith’s famed Iron Brigade—consisting ofthe 2d, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin, the 19th Indiana, and the 24thMichigan—arrived on the field. Reynolds himself pointed out theMidwesterners’ first objective: the repulse of Archer’s brigade, thencresting McPherson’s Ridge through the Herbst family woodlot.20

0R i dg eRail roadH420440A . P. H I L LHerr’s Tavern480460Map 342Tby RunhedHerbstHAITC ULSE0R46FAIEIRFLDROADREYNOLDST HMcPhersonVICHBERaiRGhedBUnisRSU n fiLutheranSeminaryAM0PIl ro a40KEd4000PennsylvaniaCollegeG E T T YSB U R G400Yards500County AlmsHouse1 July 1863D AY 1L AT E MO R NI NGCARLISLE ROAD460R i d g ea kO420nis01000380Kuhn’sBrickyard400ADU n fi400r ’ sH e rERughEWilloDPMcEREM0H42ge’s UMGUR0

Seconds later, Reynolds fell from his saddle, killed instantly by abullet to the back of the head. Unaware of Reynolds’ death, theIron Brigade drove Archer’s men out of the woodlot and backacross Willoughby Run. Pvt. Patrick Maloney of the 2d Wisconsincaptured Archer himself, making him the first general officer in theArmy of Northern Virginia to be captured since Lee had assumedcommand thirteen months earlier. The Iron Brigade learnedof Reynolds’ fall only after they withdrew to the high ground inHerbst’s woods to reorganize.The Midwesterners’ position south of the Chambersburg Pikewas not as secure as it seemed. Reynolds’ death made Maj. Gen.Abner Doubleday the senior Union officer on the field, and hefound his attention quickly drawn north of the turnpike. That wasbecause Davis’ troops, emboldened by their success against Cutler,continued to push eastward; if left unchecked, the onrushingConfederates could sweep in behind the Union troops fightingsouth of the road. To stop Davis’ advance, the Iron Brigade’s 6thWisconsin and two New York regiments charged from south ofthe pike to the lip of an unfinished railroad cut that many of Davis’troops were using for cover. The Federals’ sudden appearancemade prisoners of hundreds of Confederates who found themselves trapped within the railroad cut’s steep earthen walls. Lt. Col.Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin ordered a Mississippi officer,Death of Reynolds by Alfred R. Waud (Library of Congress)22

“Surrender, or I will fire!” According to Dawes, the man “repliednot a word but promptly handed me his sword.” Then, “six otherofficers came up and handed me their swords,” Dawes recalled. Thesuccessful charge consequently averted a Union disaster, inspiringDoubleday to hold McPherson’s Ridge in the belief that it had beenReynolds’ “intention to defend the place.”The fight at the railroad cut ended about 1200, and an eeriecalm settled over the battlefield. When the third phase beganaround 1400, the battle changed in three important ways. First,both sides received substantial reinforcements. Second, the morning’s fight west of Gettysburg now extended to the north of town.Third, General Lee arrived on the battlefield and took a significantmeasure of tactical control over his army’s actions.Phase three began when General Heth renewed the contestsouth of the Chambersburg Pike by advancing his two remainingfresh brigades against the Iron Brigade. The Midwesterners’ linehad been bolstered by two newly arrived I Corps brigades. Fightinggrew in intensity all along McPherson’s Ridge, but nowhere didthe carnage exceed that in the Herbst woodlot, where the leftflank of General Pettigrew’s North Carolina brigade assaulted theIron Brigade’s line. Fate had thrown two of the largest regimentson the field—the 496-man 24th Michigan and the 800-man 26thNorth Carolina—against each other. Col. Henry Morrow of the24th Michigan considered his position to be “untenable,” but hereceived orders that the line “must be held at all hazards.” The 26thNorth Carolina advanced “with rapid strides, yelling like demons,”Morrow reported. Before the fighting ended, at least eleven NorthCarolina color bearers—and their 21-year-old colonel, HenryK. Burgwyn Jr.—fell to Iro

CMH Pub 75-10. Cover: Scene from the Gettysburg Cyclorama painting, The Battle of Gettysburg, by. Paul Phillippoteaux, depicting Pickett's Charge and fighting at the Angle.