Transcription

YEMEN: THE 60-YEAR WARGERALD M. FEIERSTEINFEBRUARY 2019POLICY PAPER 2019-2

CONTENTS*SUMMARY*1INTRODUCTION*1HISTORIC ANTECEDENTS*4A TALE OF FAILED TRANSITIONS: 1962- 90*9POPULISM IN THE NORTH REFLECTED IN SIX SA’DAH WARS*12THE ARAB SPRING AND A NEW PUSH FOR NATIONAL UNITY*17REPEATED ATTEMPTS TO ADDRESS YEMEN’S SYSTEMICDIVISIONS*20EXTERNAL FACTORS IN THE CONFLICT*25CAN YEMEN’S PROBLEMS BE SOLVED?*27CONCLUSION*29RECOMMENDATIONS

SUMMARYThe root causes of the ongoing civil conflict in Yemen lie in the failure ofYemeni society to address and resolve the popular anger and frustrationarising from political marginalization, economic disenfranchisement, andthe effects of an extractive, corrupt, rentier state. This systemic failure hasproduced a cycle of violence, political upheaval, and institutional collapsesince the creation of the modern Yemeni state in the 1960s, of which thecurrent conflict is only the latest eruption.Over the course of the conflict, Yemenis have come together repeatedly inan effort to identify solutions to these problems, and the result has beena fairly consistent formula for change: government decentralization andgreater local autonomy, a federalized state structure, greater representationin parliament for disenfranchised populations, improved access to basicservices, health and education, and a more even playing field for economicparticipation. But none of these reform programs has been implementedsuccessfully. Thus, success in ending Yemen’s cycle of violence andits 60-year civil war will depend on the political will to follow through onimplementation and the development of institutional capacity to carry it out. The Middle East InstituteThe Middle East Institute1319 18th Street NWWashington, D.C. 20036

perspective is correct, a resolution of thecurrent conflict will only be a preludeto the next outbreak of violence. ToYemen’s political transition, whichavoid that outcome, Yemenis not onlybegan with much hope and optimism inmust agree on steps needed to build2011, collapsed by the fall of 2014 whensustainable solutions to the country’sHouthi insurgents occupied Sana’a, theproblems but must also demand thatcapital, with the support of forces loyaltheir leaders implement them.to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh.Intervention by a Saudi-led coalitionof primarily Gulf Cooperation Council(GCC) member states in March 2015turned the civil conflict into a broaderwar, attracting regional and international Yemen bears all the hallmarks of a failedattention, although at its core this state as described by Daron Acemogluremains a civil war, not a proxy fight. and James Robinson in their landmarkNeither side in the conflict has been able book, Why Nations Fail.1 The countryto gain a significant military advantage suffers from an extractive politicalin the ensuing years while persistent and economic system. By definition,efforts by the international community, such systems are characterized by theunder UN leadership, have also been concentration of power in the hands ofunsuccessful in brokering a sustained a narrow elite and place few constraintsreturn to negotiations and a resumption on its exercise of power. As a generalof the political process.principle, Acemoglu and Robinsonassert, extractive systems like Yemen’sMost analyses of the Yemen conflictare vulnerable to violence, anarchy, andsince 2014-15 have focused on thepolitical upheaval and are unlikely toissues and circumstances that led toachieve growth or make major changesthe fighting in isolation from the largertoward more inclusive institutionsproblems that have long confrontedsuccessfully.Yemen. But, in my view, the currentconflict is more accurately seen as a But the origins of the current conflictcontinuation of over 60 years of failed in Yemen go beyond even thestate formation leading to a cycle of consequences of the rentier stateviolence, coups, assassinations, and described by Acemoglu and Robinson.open warfare. The shotgun unification In fact, the political crisis that emergedof North and South Yemen in 1990 only in mid-2014 and metastasized into theserved to add a new layer of complexity current war is only the latest eruption in ato the already fraught political, social, cycle of violence that has shaken Yemenand economic environment. If this repeatedly for nearly 60 years. Nor is it theINTRODUCTIONHISTORICANTECEDENTS1

MAP OF YEMEN(Earthstar Geographics Esri, HERE, Garmin)TIMELINE1962: Uprising against the Imamate in northern Yemen1978: Beginning of Ali Abdullah Saleh’s presidency of North Yemen andthe Yemeni Socialist Party’s rule in South Yemen1990: Unification of North and South Yemen1994: Civil war2004-10: Six Sa’dah wars2011: Arab Spring and anti-Saleh uprising (February)End of Saleh presidency (November)2013: National Dialogue Conference2015: Houthi insurgents occupy Sana’a 2

most violent or longest lasting of theseconflicts.2 There is no ten-year period inYemen’s history since the 1960s that hasnot witnessed violent conflict, coups,or civil insurrection. Beginning with the1962 uprising against the Zaydi Shi’atheocracy, or Imamate, Yemenis haveyet to find a means to build institutionsof state and society that can addresssuccessfully the grievances of politicaland economic marginalization, and thealienation of populations disadvantagedby governing institutions and ethnic andsectarian discrimination. The unificationof North and South Yemen in 1990 onlyadded an extra layer of complexity tothe country’s problems.highlands. But, beyond that, thedelegates to the most representativebody of Yemenis ever assembledprovided recommendations on a broadarray of critical issues facing the country,including economics, governance, andthe structure of military and securityforces.The failure of state formation in Yemen,then, is not a result of the inability ofYemenis to understand the challenges,devise solutions, or create a road mapfor a unified state at peace with itself. Thefailure, instead, rests with the inability ofYemenis to implement the agreementsreached. In at least two instances, in1994 and in 2014, signed agreementsThe failure to build the institutional were followed within weeks by a newstructures of a modern, cohesive state, outbreak of conflict.however, does not reflect an inability toYemen will not succeed in breakingunderstand the nature of the problemsthis decades-long cycle of violenceor devise reasonable solutions. Yemenisuntil there is a national consensus onhave come together repeatedly in effortsthe need to put in place the structuresto resolve their recurring challenges.that enable implementation of agreedMoreover, the efforts to find solutionsreforms: capable local governinghave generally advocated similarinstitutions, equal access to basic socialreforms: decentralization and enhancedservices including health and education,local autonomy, equal geographicand an end to the extractive political andrepresentation in national government,economic systems that allowed a small,federalism, and an equitable distributionlargely northern tribal elite to dominateof the country’s natural resources. Thethe country, exploit its resources for theirmost comprehensive effort followed theown narrow interests, and block accessArab Spring uprising against Presidentto the political and economic arena toSaleh’s government in 2011. For over athe vast majority of Yemeni citizens.year, more than 500 delegates laboredto produce proposals to resolvepersistent regional divisions withinYemen and the grievances of the Zaydimajority population of the northwestern3

A TALE OF FAILEDTRANSITIONS: 1962-90Rebellions in the 1960s against theocraticrule in the North and British occupation inthe South ushered in decades of politicaland economic turmoil throughout Yemen.By the end of the 20th century, themodern Yemeni state emerged but wasunsuccessful in addressing the failure ofstate formation that has plagued Yemensince the revolt against the Imamate.THE IMAMATEDEFEATED: TRIUMPHOF SHEIKHSNorthern Yemen was ruled for a millenniumby a theocracy, the Imamate, which drew itssocial and political support from the ZaydiShi’a tribes of the northwestern highlands.But the Imamate’s economic survival restedon the exploitation of the relatively richer,predominantly Shafi’i Sunni midlands,including Taiz, Ibb, al-Baida, and the RedSea coastal region, or Tihama.By the early 1960s, an Arab nationalistmovement, the self-styled “Free Yemenis,”emerged in the midlands region and,in 1962, launched a full-scale rebellionagainst the Imamate, with the supportof Egypt under President Gamal AbdelNasser. That struggle persisted until theend of the decade, when the republicanin the country, however, as the traditionalnorthern highlands tribal leaders retainedpositions of power and influence in the newpolitical order.But, in challenging the rule by the sadahor sayyids, a Shi’a religious leadership thatclaimed its legitimacy based on its directdescent from the Prophet Muhammad, theFree Yemenis developed an Arab nationalistcounter-narrative that would have longterm implications for Yemen’s internalcohesion. While it made political sense topaper over sectarian differences betweenZaydi Shi’a and Shafi’i Sunni populations, theFree Yemenis introduced a new concept:“real” Yemenis were the descendants ofthe Qahtanis – southern Arabian tribes thatwere the original inhabitants of Yemen. Bycontrast, they asserted that the sayyidsruling Yemen were Adnanis – descendantsof northern tribes that immigrated tosouthern Arabia following the arrival ofIslam and became the rulers of Yemen.Over the course of the eight-year rebellionagainst the Imamate, this distinction (whichStephen Day notes is likely mythical4)became an important factor in building thebroad, pro-republican consensus that wonthe war and established the Yemen ArabRepublic (YAR).The midlands population prospered inthe first decade of republican rule. TheShafi’i business community developedlocal cooperative organizations and beganmanaging its own affairs. Keeping their taxforces triumphed.3 The demise of the revenue available for local improvements,Imamate and rise of the republic did not the region’s political leaders invested in thesubstantially change the political balance infrastructure that allowed the economy to 4

grow. By the end of the civil war and thereintegration of the highlands elites intothe national consensus, Stephen Daywrites, an informal balance of poweremerged between highlands elites andthe lowlands merchant class. “In effect,”Day notes, “informal power-sharingallowed highland elites to maintainpolitical hegemony, while businesselites from the western midland andcoastal regions ran the economy.”5This extended to the government aswell, with an informal power-sharingarrangement that the president of therepublic would represent the highlandselites while the prime minister would bea midlands figure.6When Ali Abdullah Saleh becamepresident in 1978 following theassassination of Ahmad al-Ghashmi, therough balance between highlands andlowlands interests began to unravel.Saleh reintroduced the exploitativetaxation system not seen since therule of the Imamate. Citizens in themidlands region were once againtaxed at a rate approximately doublethat paid by the highlands population.7At the same time, Saleh’s policiesfavored the rise of highland tribalsheikhs, challenging the formerlydominant sayyids and their allies. Thesheikhs, especially Abdullah al-Ahmar,the paramount sheikh of the Hashidtribal confederation, assumed leadingroles in the republic’s political circles.Building on their political dominance,the sheikhs, especially those of theHashid and Bakil tribal confederations,5 next entered into competition with thetraditional midlands merchant classfor economic control. Under Saleh,therefore, northwestern highlands tribalsheikhs were the principal beneficiariesof the extractive political and economicsystem that has plagued Yemen’sdevelopment ever since. The discoveryof oil in Marib Governorate in 1984provided new opportunities for corruptexploitation by the highlands elites andbecame a new source of grievance forthe marginalized populations of theNorth and the midlands.A UNITY ACCORDIN 1990 QUICKLYFOUNDERSNorth and South Yemen enjoyed a rollercoaster relationship from independenceuntil their unity agreement in 1990.At various times, both Sana’a andAden promoted unification as interestwaxed and waned depending on thepersonalities of the leaders in the twostates. The charter of the Yemeni SocialistParty (YSP), the ruling party in SouthYemen after its formation in 1978, forinstance, employs Marxist terminology,declaring that the revolutionary strugglein Yemen is “dialectically correlated in itsunity”8 to argue that unity between Northand South is an essential component ofYemen’s evolution. But the leaders of thePeople’s Democratic Republic of Yemen(PDRY) were responsible for the June1978 assassination of YAR President alGhashmi, and the two states fought a

brief border war between January and March1979. Despite the persistent tensions, thetwo sides managed to develop a dialogue.PDRY President Ali Nasser Mohammedvisited Sana’a in November 1981 and, afterthe two presidents met in Kuwait, Salehtraveled to Aden.The discovery of oil in the border regionsbetween the two states provided both sideswith a financial incentive to strengthentheir relations. In April 1990, Saleh and AliSalem al-Beidh, secretary-general of theYSP, signed a unity agreement to mergethe PDRY and YAR into a new, single entity,the Republic of Yemen (RoY). Aside fromorganizing the basic elements of a newgoverning structure, the two-page dealwas remarkably short on detail. Underthe terms of the agreement, over thecourse of a 30-month interim period a fivemember Presidential Council would draft aconstitution. Until then, the council wouldrule by decree.the much more populous North based onthe unity agreement, had envisioned thatthey would dominate the political structureof the newly-unified state. In particular,they expected to do well in parliamentaryelections scheduled for 1992 (eventuallyconducted in 1993), and perhaps win amajority of seats based on their anticipatedsupport among northern voters. But theywere disappointed when they finished apoor third after Saleh’s General People’sCongress (GPC) and the newly formernorthern Islamist party, Islah. Rather thandominating the new political arrangement,the southerners saw their political influencerapidly dissipating.Economically, conditions in the PDRY werefar poorer than in the North at the timeof unification, a product not only of statecontrol of the economy but also becauseof the declining revenue stream fromthe Aden port. The PDRY leadership hadcounted on the port as the main economicengine that would finance southernIn addition to the financial motivation fromdevelopment programs, but the closurethe discovery of oil, two other factors droveof the Suez Canal from 1967-1975 forcedthe South’s agreement to the “shotguninternational shipping to develop newmarriage” with the North in 1990. First,trade routes and left Aden uncompetitive.the collapse of the former Soviet UnionNevertheless, PDRY citizens did enjoydeprived the PDRY of its most significantbenefits unmatched in the South, includingpolitical and economic partner. Second, thesubsidized basic commodities as wellbrutal 1986 intra-YSP conflict significantlyas guaranteed employment in stateweakened the PDRY government.9enterprises. The South also compared wellPopulations on both sides of the border to the North on provision of basic services,greeted the announcement of unity with particularly in health care and education.10enthusiasm. But southern satisfaction Those advantages began to erode aswith the new RoY quickly waned. Southern the North introduced its crony capitalistpolitical leaders, who initially enjoyed a50:50 power sharing arrangement with 6

economic system and the highland Aziz Abdul Ghani, an experienced,tribal elites began to extend their midlands GPC technocrat, as primeeconomic domination to the South.minister.Thus, by the end of 1993, frustratedsoutherners were openly rejectingunity and advocating a return toan independent state. After a lastattempt at a political resolutiontothegrowingNorth-Southconfrontation failed (see below fora discussion of the negotiations thatproduced the “Document of Pledgeand Accord”), southern leadersdeclared independence and theNorth launched military operationsto retake the South.Those same core issues continueto plague North-South relationsuntil the present time and form thebasis of southern challenges notonly to the Hadi government butmore broadly to the idea of Yemeniunity. The social and economicconsequences of the civil conflictwere harsh for southern citizens.The Saleh government acceleratedthe expansion of the North’s rentierpolitical and economic system in theSouth. Aden itself was ransacked byvictorious highland tribes, southernThe brief civil war in 1994 thatcivil servants and military personnelfollowed the collapse of politicalwere dismissed, and southernersnegotiations failed to resolve thecharged that northerners plunderedbasic issues that led to the conflict.the South’s energy, mineral, andAlthough Saleh maintained powerfish resources. In sum, notes Aprilsharing arrangements with theLongley Alley, “two profoundlySouth, appointing Abed Rabbodifferent narratives took shape” aboutMansour Hadi as vice president inthe outcome of the conflict. “Underplace of the exiled Ali Salim al-Beidh,one version, the war laid to rest theStephen Day observes that Saleh wasnotion of separation and solidified“mainly interested in the appearancenational unity. According to the other,of power sharing, not genuinethe war laid to rest the notion of unityrepresentation of southern interestsand ushered in a period of northernin government.”11 The number ofoccupation of the South.”12southerners in the Yemen cabinetdropped significantly as Saleh By the middle of the following decade,formed a coalition government with southern anger over their treatmentthe Islah party and appointed Abdul at northern hands began to boil over.7

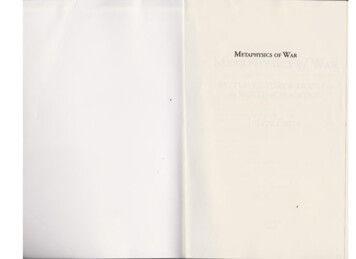

The outcome of the civil war, in particularthe forced retirement of southern civilianand military officials, contributed to the riseof an organized opposition movement in theSouth.13 Beginning in a series of peacefulprotests in 2006, the movement, initially castas a “local association for military retirees,”evolved into a large-scale, generallypeaceful but occasionally violent protestmovement, al-Hirak. Pursuing his well-wornstrategy of divide and conquer (“dancingon the heads of snakes”), Saleh struggledto dilute the southern movement, offeringsome concessions to military retirees andadvocating resolution of land disputeswhile continuing efforts to marginalize oreliminate political opposition.Town taken by North Yemen forces in Daleh, Yemen on May13, 1994. Distribution of weapons to men of Murkula. (LaurentThe government’s inability to defeat theHouthis, an armed Zaydi insurgency, inthe northwest (see below) encouragedthe al-Hirak movement to intensify its owncampaign, and it clashed more aggressivelywith government forces. The demands ofthe al-Hirak movement focused on accessto government jobs and benefits and moreequitable resource sharing, especially in theenergy sector, according to April LongleyAlley. She cites the late mayor of Sana’aand advocate of decentralization, AbdulQadir al-Hilal, stating “even within a singlegovernorate, one district will complain ofmarginalization or discrimination whencompared to another. However, in theSouth, this feeling of marginalization hastaken on a political dimension becauseVAN DER STOCKT/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images) 8

of the absence of political opportunitiesand because it used to be an independentstate.” By the time of the Arab Spring in 2011,southern support for al-Hirak and new callsfor separation from the North were again onthe rise.15POPULISM IN THENORTH REFLECTED INSIX SA’DAH WARSMany of the unresolved issues from therepublican revolt of the 1960s and itsaftermath, particularly in the years ofSaleh’s rule, helped to trigger the Houthirebellion in six Sa’dah wars between June2004 and February 2010. Like the post-unitySouth, northern Zaydi populations grewincreasingly militant over the growth ofextractive political and economic systemsduring the Saleh era and the failure ofrepublican Yemen to provide equitablesharing of resources. Zaydi revivalism beganto grow as a counter to this marginalizationin the 1980s, predating the rise of theHouthi movement. Marieke Brandt notedin her comprehensive history of the Houthimovement that “the economic and politicalmarginalization of the Sa’dah region, theuneven distribution of economic resourcesand political participation, and the religiousdiscrimination against its Zaydi populationprovided fertile soil in which the Houthimovement could take root and blossom.”16A displaced Yemeni child from the Sa’adah region carries jerrycans at the Mazraq IDP camp in northern Yemen on December10, 2009. (KHALED FAZAA/AFP/Getty Images)9

Indeed, the scion of the Houthi clan,Badr al-Din al-Houthi, and his sonHusayn, enjoyed strong reputationsin Sa’dah as much for their deepcommitment to community serviceas for their position as sayyids. Itwas that role in the community thatmade them natural leaders of the“Believing Youth” movement in the1990s. By the early 2000s, Husaynhad developed a broad platformarticulated in a series of Zaydirevivalism,and intense criticism of the Salehregime for its economic neglect andunderdevelopment of the North.Brandt notes that, despite Husaynal-Houthi’s complaint that thegovernment was supporting Sunniand Salafist communities at theexpense of the Zaydis, his appealwas not restricted to the Zaydicommunity, but was pan-Islamic incontent.17 Thus, the image of the alHouthi family as the face of ZaydiShi’ism confronting the threat of“Sunnization” in the Zaydi heartland,therebyembodyingsectarianconflict, is at best an incompletenarrative of the Houthi movementeven if it is not an entirely inaccurateone. “In the local context,” Brandtwrites, “the Zaydi revival was far morethan a sectarian movement: underHusayn’s direction, it also embracedpowerful social-revolutionary andpolitical components.”18Nevertheless, the Saleh regimefocused its attack on the Houthirebellion by exploiting the Houthis’support for the reintroduction ofseveral predominantly Shi’a religiousobservances,includingAshura,maintaining that the Houthis werenot only advocates of Zaydi Shi’ismbut in fact represented the questfor a return of the Imamate and theintroduction of Iranian-style TwelverShi’ism.Sana’a’s angle of attack on theHouthis re-opened a second,unresolved wound from the antiImamate rebellion of the 1960s. Asnoted previously, pro-republicanforces in the 1960s created anarrative of Yemen’s earliest historythat distinguished between socalled “real Yemenis” – the Qahtani ororiginal South Yemen tribes – versuslater arrivals – the Adnani tribes fromnorthern Arabia and especially thenon-tribal sayyids, the “strangersin the house”19 who establishedthemselves in the northwesternhighlands as religious scholars andtribal mediators. The distinctionmarginalized the sayyids, traditionalrulers of Yemen’s Imamate theocracy. 10

A Yemeni anti-government protester shows her hands, painted with the colors of the flag and the slogan ‘Welcomerevolutionaries,’ during a demonstration in Sana’a on December 23, 2011 to reject an amnesty given to President AliAbdullah Saleh in a deal that eases him out of office. (MOHAMMED HUWAIS/AFP/Getty Images)Within the Zaydi population, where theHouthis did not enjoy universal support,criticism of their movement often reflectedthis anti-sayyid, Qahtani viewpoint thatinterpreted the Houthi movement as antidemocratic and backward looking.The principal beneficiaries of thismarginalization of the sayyids werethe tribal sheikhs of the northwesternhighlands and especially the newlyminted “revolution sheikhs”20 who hadfought on behalf of republican forces in theeight-year civil conflict and profited fromthe rise of Yemen’s rentier political andeconomic system. “The sheikhs benefiteddisproportionately from the republicansystem,” Brandt notes, “at [the] local level,in many respects they were the republic.”21But the elevation of the sheikhs was notsynonymous with the rise of the tribes.11 Once again, Brandt notes that “the politicsof patronage was a double-edged sword:rather than ‘nurturing’ the tribal systemgovernmental patronage has driven awedge between some influential sheikhsand their tribal home constituencies andhas generated discontent and alienationamong many ordinary tribal members.”22 Inthe conflict between sheikhs and sayyids,many of the tribes were pulled towardthe Houthi movement by the failure of thesheikhs to use their new-found power andinfluence in the republican government tosupport the tribes.Despite its enormous military advantage,Sana’a was unable to defeat the Houthirebellion, and the fighting divided thenorthern population. “Instead of puttingdown the rebellion,” Brandt writes, “thegovernment’s military campaigns triggered

destructive cycles of violence and counterviolence in Sa’dah’s tribal environment,which, step-by-step, engulfed Yemen’sNorth. During these battles, Sa’dah’scitizenry became increasingly polarizedalong government-Houthi lines. Fromthe second war, it became evident that asignificant number of people joining theHouthis’ ranks were no longer religiouslyor ideologically motivated but were drawninto the conflict for other reasons.” By theoutbreak of the Arab Spring in February 2011,the Houthis had built the most effectivemilitary force in the country and had takencontrol of all of Sa’dah Governorate as wellas large portions of neighboring Amranand al-Jawf. Although the so-called “Northof the North” was momentarily at peace,the popular anger and frustration directedtowards the Saleh government had by nomeans decreased.guaranteeing that he and his son AhmedAli would keep their grip on power for theforeseeable future. He ignored earliercommitments to the political oppositionthat he would negotiate new rules forplanned parliamentary elections deferredfrom 2009 and re-scheduled for mid-2011.But Saleh’s sense of confidence provedmisplaced. When the streets erupted inFebruary 2011, the government was caughtby surprise. Inspired by youth revolutionsin Tunisia and Egypt, young, urbanizedYemenis took to the streets to demand thatSaleh step down. The protesters focusednot only on the corruption and cronyismof the Saleh government but also on thepolitical, economic, and social stagnationthat beset the country and threatened todeprive young people, including educatedyouth, of any prospect for a secure s, the Houthis, tribal youth,and the Shafi’i population in the midlandsjoined in the protest demonstrationsand demanded, beyond Saleh’s ouster,that the transition seek to address theBy the end of 2010 and the beginning of underlying conditions that had prevented2011, President Saleh was basking in a Yemen’s development as a modern state.vision of overwhelming political mastery. An International Crisis Group analysisHe portrayed his successful hosting of suggested that the popular proteststhe GCC Cup soccer tournament in Aden promoted cooperation between northernin December 2010 as evidence that his and southern protesters and “broke throughcontrol of the South was uncontested. In the barriers of fear.” 23the far North, Saleh had convinced himselfMeanwhile, Saleh’s too clever by halfthat he had mastered the Houthi threat andpolitical maneuvering had deeply angeredthat the lull in fighting would be sustained.the opposition. General Ali Mohsen, Saleh’sHis domination of the National Assemblyheir apparent for decades until he promotedallowed him to push through legislationhis son, Ahmed Ali, as his successor, noTHE ARAB SPRINGAND A NEW PUSH FORNATIONAL UNITY 12

longer stood firmly behind his old comradein-arms. Thus, Saleh was left without friendsor negotiating partners as he scrambled toparry the street demonstrations and quellthe uprising. Running out of options, hetabled a proposal to step down, triggeringa negotiating process that would stretchout over many months, punctuated bysporadic street battles in Sana’a and othermajor cities as well as an assassinationattempt that spared Saleh (albeit seriouslywounding him) but killed and injured anumber of his senior advisors, includingPrime Minister Abdul Aziz Abdul Ghani.with his constant twisting (as well as hispersonal attacks on GCC Secretary-GeneralAbdul Latif al-Zayani, who the Saudis haddesignated to help negotiate the transitionagreement). When King Abdullah calledSaleh and told him that his time was up,Saleh was left with little choice but tocomply. The signing ceremony took placein Riyadh in November.Yemenis saw the protest movement andthe end of the Saleh regime as a newopportunity to resolve the deeper politicaland economic crisis confronting thecountry. Not only the political oppositionbut also Saleh’s own GPC supported thedemand for a broad-based initiative toaddress Yemen’s deep-seated problems.Thus, among its other elements, thetransition document, the GCC Initiativeand Implementing Mechanism, includeda requirement to conduct within its twoyear timeframe a National DialogueConference (NDC) to address the full rangeof political, economic, and social problems,including specifically southern and Houthigrievances. Launched in 2013, the NDCquickly organized itself into working groupsand began addressing a broad agenda ofissues. (See below for a discussion of theNDC recommendations.)In desperation, Saleh turned to theinternational community to help him retainhis grip on power. Having frozen cooperationwith the U.S

writes, an informal balance of power emerged between highlands elites and the lowlands merchant class. "In effect," Day notes, "informal power-sharing allowed highland elites to maintain political hegemony, while business elites from the western midland and coastal regions ran the economy."5 This extended to the government as