Transcription

Exotic Aesthetics: Representations of Blacknessin Nineteenth-Century Russian PaintingMaria TaroutinaDespite the recent surge of scholarly interest in depictions of Black subjects inEuropean art, the case of Russia remains largely under-examined.1 In the pastdecade, a number of important studies have addressed questions of race inthe Soviet context, but only a handful of publications have analyzed Russianrepresentations of Black subjects and native Russians of African descent inthe long nineteenth century.2 Given that Russia lacked a physical colonialpresence in Africa and that people of color were generally absent from itsmajor cities, it is hardly surprising that there were considerably fewer representations of Blackness in Russian fine and decorative arts as compared to theother great powers. Those that do exist are often quite striking in their radicaldepartures from established European conventions. Accordingly, the presentarticle focuses on a few representative works by canonical nineteenth-centuryRussian artists: Karl Briullov, Vasilii Polenov, and Il ia Repin, paying closeattention to the different ways in which their paintings encoded a complex setof interconnected ideas about Russian exceptionalism, imperialist aesthetics,and nationalist versus cosmopolitan pictorial sensibilities. Lastly, it considersthe ways in which these paintings both reflected and contributed to the evolving Russian discourses on race and representation in the nineteenth century.Beginning with Peter I’s reign, it became increasingly fashionable amongthe Russian elite to import Black subjects as household servants, as wasthe practice in the rest of Europe at the time.3 Peter himself, as well as his1. See for example, David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. eds., Image of theBlack in Western Art, vols. 1–5 (Cambridge, Mass., 2010–2014); Adrienne L. Childs andSusan Houghton Libby, eds., Blacks and Blackness in European Art of the Long NineteenthCentury (New York, 2016); Denise Murrell, Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manetand Matisse to Today (New Haven, 2018).2. On representations of African Americans and racial minorities in Soviet art seeChristina Kiaer, “African Americans in Soviet Socialist Realism: The Case of AleksandrDeineka,” The Russian Review 75, no. 3 (July, 2016): 402–33; and Steven S. Lee, The EthnicAvant-Garde: Minority Cultures and World Revolution (New York, 2015). On nineteenthcentury Russian representations of Black subjects and native Russians of African descent,see Allison Leigh, “Blood, Skin, and Paint: Karl Briullov in 1832,” in Maria Taroutina andGalina Mardilovich, eds., New Narratives of Russian and East European Art: BetweenTraditions and Revolutions (New York, 2020), 15–31; Paul H.D. Kaplan, “Karl Briullovand the Russian Representation of Black Africans in the Age of Pushkin,” in DavidBindman and Henry Louis Gates Jr., eds., The Image of the Black in Western Art: From theAmerican Revolution to World War 1, vol. 4 (Cambridge, Mass., 2012), 261–76; and RichardBorden, “Making a True Image: Blackness and Pushkin Portraits,” in Catharine TheimerNepomnyashchy, Nicole Svobodny, and Ludmilla A. Trigos, eds., Under the Sky of MyAfrica: Alexander Pushkin and Blackness (Evanston, IL, 2006), 172–95.3. Some of the earliest records of Black subjects at the Russian court date back toMichael I’s reign (1613–1645). They were purchased and brought over to Russia as slavesby way of Tripoli and Constantinople. According to the records of the Russian MinistrySlavic Review 80, no. 2 (Summer 2021) The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of theAssociation for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studiesdoi: 1.81 Published online by Cambridge University Press

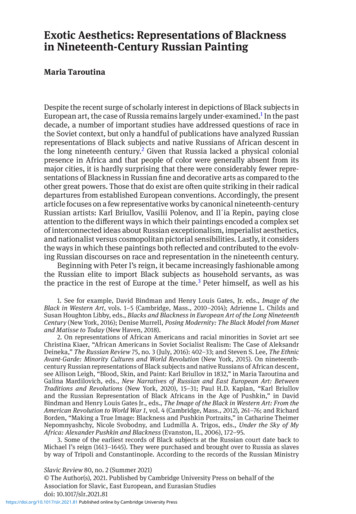

268Slavic Review arious successors, acquired a number of people of color to embellish theirvroyal courts—a custom that continued well into the twentieth century untilthe abrupt end of the tsarist regime in 1917.4 These arapy, efiopy, or negry—blackamoors, Ethiopians, or negroes—were often featured in commissionedportraits of the nobility, where their presence served to emphasize the beauty,worldliness, and “whiteness” of the principal sitter and in so doing underwrote the aristocrat’s social status, rank, and dignity.5 The inclusion of anarap signaled wealth and consumption and they were often paired withexpensive and exotic materials such as jewels, baskets of fruit or flowers, andpet animals.Thus, for example, in Karl Briullov’s Portrait of Countess Julia Samoilovaand her adopted daughter Giovanina and a Black Page (1832–34) (Fig. 1), theyoung Black attendant serves as both a conceptual and aesthetic “foil” to hisaristocratic mistress. While the whiteness of the countess’s skin is accentuatedby her dark hair and the deep burgundy curtain behind her, the Blackness ofthe African boy is heightened by the pale blue sky visible through the window against which he is silhouetted. Paul Kaplan suggests that this conspicuous visual signifier of “difference” was meant to emphasize Samoilova’sfundamentally “western” identity in light of Russia’s ongoing “complicatedrelationship with western Europe, involving profound cultural indebtedness and admiration, religious difference, and feelings of cultural and socialinferiority.”6 Perhaps even more importantly, lurking under the surface ofBriullov’s painting is the restive issue of Russians’ perceived racial impurity and their semi-Asian identity as a result of almost two hundred years ofMongol domination. Many members of the Russian aristocratic, military, andcultural elites—such as the Usupovs and Sheremetevs—had Tartar and TurkicPersian ancestry. Within this context, the Black boy functions as a rhetorical visual antithesis and, by extension, a symbolic guarantor of Samoilova’swhiteness—a trope further accentuated by the child’s admiring, upwardglance towards his mistress. His demeanor is directly mirrored by the stanceof the small spaniel, tacitly signifying their equivalence in the social hierarchy—an insinuation that is further emphasized by the fact that both the boyof Foreign Affairs, Peter I was personally responsible for bringing over a number ofBlack servants from Holland in 1697. By the late eighteenth century, chattel slavery wasvirtually abolished in Russia and upon their arrival, Black subjects would be given theirpersonal freedom in exchange for a lifetime of service obligation. By the early nineteenthcentury, many of these Black servants would be paid an annual wage and at the fin desiècle, in some instances, they earned as much as 600–800 rubles per year. For moreinformation, see Allison Blakely, Russia and the Negro: Blacks in Russian History andThought (Washington, 1986), 13–16.4. During Peter I’s reign, the Russian Imperial Court instituted a special serviceposition called the “Blacks of the Imperial Court” (Arapy Vysochaishchego Dvora). Manyof these servants went on to marry Russian women, father mixed-race children, and liveindependently of the court. For more information on this, see: Nina Tarasova, “ArapyVysochaishchego Dvora na sluzhbe u rossiiskhikh imperatorov kontsa 19-nachala 20veka,” in Nina Tarasova, ed., Trudy Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha: Kul tura i isskustvorossii, vol. 40 (St. Petersburg, 2008), 227–43; and Tarasova, “Vysochaishego dvorasluzhiteli,” Nauka i zhizn no. 10 (2014): 136–41.5. I use the term “negro” as a translation from the Russian word negr, which wasemployed as a neutral descriptive term in the nineteenth century.6. Kaplan, “Karl Briullov,” 271.https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2021.81 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Representations of Blackness in 19th-Century Russian Painting269Figure 1. Karl Briullov, Portrait of Countess Julia Samoilova and her adopteddaughter Giovanina and a Black Page, 1832–34, oil on canvas, 269 x 200 cm. Hillwood Museum and Gardens, Washington, D.C.and the dog wear prominent collars around their necks. Samoilova’s adopteddaughter Giovanina also looks up lovingly at the countess completing the triangle of deferential gazes. The fact that she is not Samoilova’s biological childand is close in age to the Black boy starkly and poignantly highlights the different prospects of the white adopted child and her Black counterpart.https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2021.81 Published online by Cambridge University Press

270Slavic ReviewWhile the inclusion of the Black boy allowed both the sitter and the artistto assert their fundamental cosmopolitanism and European savoir faire, it isimportant to note that at the time that this work was painted, chattel slaverywas officially illegal in Russia and representatives of Tsar Alexander I hadargued for the abolition of the African slave trade at the international Aixla-Chapelle Congress of 1818. As such, Briullov’s depiction of the demeaningslave collar around the boy’s neck is strikingly incongruous in light of the provisional elimination of slavery by 1834 throughout most of Europe, includingItaly, where the work was painted. Indeed, Samoilova’s portrait reflected anestablished eighteenth-century European convention, but by the 1830s, depictions of Black attendants were increasingly few and far between in Europeanart. Consequently, in its adoption of an already outdated pictorial mode, thispainting was strangely aberrant in its self-conscious antiquarianism.Around the same time, Briullov produced a number of other fairly unorthodox, if not outright transgressive, works featuring Black subjects, such ashis two paintings of Bathsheba (1830; 1832), The Sack of Rome by Gensericthe Vandal I (1835–36), and most notably, Ibrahim Embracing the Countess(1847–49) (Fig. 2). The latter is a watercolor illustration to Aleksandr Pushkin’sFigure 2. Karl Briullov, Ibrahim Embracing the Countess, 1847–49, watercolorand graphite on paper, 23.7 x 25.9 cm. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2021.81 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Representations of Blackness in 19th-Century Russian Painting271unfinished historical novella The Blackamoor of Peter the Great (1827–28)—afictionalized biography of his great-grandfather, Abram Petrovich Gannibal.Briullov’s image depicts the principal African protagonist, Ibrahim, passionately embracing his illicit French lover, Countess D. Akin to the dramatic colorcontrasts in the portrait of Samoilova, in this image Briullov again intentionally juxtaposed light and dark hues by silhouetting Ibrahim’s Black handagainst his lover’s lily-white shoulder. The countess returns Ibrahim’s ardentgesture by running her fingers over the side of his face, creating a mirroredwhite-on-black visual effect. Although the blazing fire in the right-hand sideof the image metaphorically symbolizes the fiery ardor of their mutual passion, the countess’s furtive gaze out of the picture frame seems to “gauge theviewer’s judgement of this provocative reconfiguration of the otherwise hierarchical relationship between black and white.”7Ibrahim Embracing the Countess is unprecedented in the history of western art in its frank visualization of a charged interracial erotic encounter.Images of white men embracing Black women or mixed-race romantic dalliances between lowborn servants certainly existed, such as Johann SamuelMock’s Lord Jonimo and the Moor Frederica (1739) and A Black Page Caressinga Shepherdess (1730s), but the reverse was virtually never pictured. Black menwere seldom, if ever, depicted in sexual contact with white women. The onlyexception are representations of Shakespeare’s Othello and Desdemona, buteven there Othello—when shown as a Black man—was usually placed somewhat apart from Desdemona and was never shown actively touching her bodyin a sexualized manner. In this sense, Briullov categorically violated an established European pictorial taboo, hinting at the possibility of dreaded miscegenation, as described in Pushkin’s narrative, where Ibrahim’s love affairresults in an illegitimate mixed-race baby who has to be secretly substitutedfor a white child and hidden away from polite society in order to avert scandaland social ruin.What is especially intriguing about this arresting image is the uneasy—one could even say fraught—coexistence of positive and negative racializedconnotations. On the one hand, as a fictionalized account of the real-lifeascension of Gannibal, the figure of Ibrahim thematizes the remarkable elevation of a Black subject within the political, military, and social hierarchyof imperial Russia. On the other hand, it consciously plays on the formulaic negative trope of Black hypersexuality, with Ibrahim portrayed as aninsatiable and sexually potent force, who is a danger and a threat to whitefemale—and by extension male—respectability.8 Unsurprisingly, Gannibal’sfamous great-grandson was subjected to the same racial stereotypes withcontemporaries often referring to his “unbridled African passions” and“ardor and sensuality,” even suggesting that it was Pushkin’s intemperance7. Kaplan, “Karl Briullov,” 274.8. For an overview of this topic, see David Brakke, “Ethiopian Demons: Male Sexuality,the Black-Skinned Other, and the Monastic Self,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 10, nos.3–4 (July-October, 2001): 501–35.https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2021.81 Published online by Cambridge University Press

272Slavic Reviewand womanizing ways that ultimately led to his fateful duel with d’Anthesand his untimely death.9At the same time, both during his lifetime and in the succeeding years ofthe nineteenth century, Pushkin was actively celebrated as an unparalleledcultural icon and a national literary genius. Rather than his exotic heritage,it was his unique talent and Russianness that were constantly emphasizedand “invocations of blackness in Russia never entailed slurs on Pushkin’sintelligence.”10 Allison Blakely explains this phenomenon by noting theabsence “in the entire history of Russia’s relationship with Black Africa [of]any type of racist ideology such as developed in the other major Europeanstates.”11 Indeed, period commentators such as the Slavophile thinker AlekseiKhomiakov claimed that Russians esteemed the poet, “the descendant of anEthiopian with pride and joy, whereas he would have been denied citizenship in the United States and would not have had the right to marry the daughter of a washerwoman in Germany or of a butcher in England.”12From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, Russian racial and imperialdiscourses were increasingly dominated by such refrains of Russia’s supposed enlightened humanism and egalitarianism in contrast to the racist andoppressive structures of western Europe.13 For instance, the historian StepanEshevskii claimed that in the case of western European nations, “the colonized ‘natives’ tended to die out because of their ill treatment by the colonizersas racially inferior.”14 Conversely, in the Russian colonial setting “inorodtsytribes do not die out, when they are confronted with Russians. They naturallytransform into Russians, absorbing specific qualities of European-Christiancivilization.”15 Similarly, the military geographer and orientalist MikhailVeniukov differentiated Russia’s benign, noncoercive colonizing methodsfrom “the terrible treatment” by Britain and Spain of their colonial subjects,concluding that “Spanish colonization as well as the English, was accompanied by the bloody annihilation of entire races and the enslavement of manymillions of people. There is nothing comparable in Russian colonization.”16In reality, however, such exalted claims belied the multiple atrocities, abuses,and coercion committed by the Russian military and bureaucratic apparatus9. See Catharine Theimer Nepomnyashchy and Ludmilla A. Trigos, “Introduction:Was Pushkin Black and Does It Matter?” in Nepomnyashchy and Trigos, eds., Under theSky of My Africa, 15–18.10. Ibid., 16.11. Blakely, Russia and the Negro, 38.12. Aleksei Stepanovich Khomiakov, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii Aleksia StepanovichaKhomiakova. Tom tretii: Zapiski o vsemirnoi istorii (Moscow, 1882), 107.13. For a broader discussion of Russian nineteenth-century conceptualizations ofrace, see Nathaniel Knight, “Chto my imeem v vidu govoria o rase? Metodologicheskierazmyshleniia o teorii i praktike rasy v Rossiiiskoi Imperii,” Etnograficheskoe obozrenie,no. 2 (2019): 114–32; and Vera Tolz, “Constructing Race, Ethnicity, and Nationhood inImperial Russia: Issues and Misconceptions,” in David Rainbow, ed., Ideologies of Race:Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union in Global Context (Montreal, 2019), 29–58.14. Stepan Eshevskii, “O znachenii ras v istorii,” in his Sochineniia (Moscow,1870), 40–41.15. Ibid.16. Mikhail Veniukov, Rossiia i Vostok: Sobranie geograficheskikh i politicheskikhstatei (St. Petersburg, 1877), 114–15.https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2021.81 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Representations of Blackness in 19th-Century Russian Painting273in the Baltics, Caucasus, and Central Asia as part of the state’s aggressiveterritorial expansion, but they do testify to the growing sense of Russia’sexceptionalism and the discursive construction of national moral superiorityin contrast to purported western opportunism and dehumanizing economicexploitation.17Against the backdrop of these debates, it is instructive to examine twovery unusual paintings of Black women by Ili a Repin and Vasilii Polenov dating from the mid-1870s. Executed during their stay in Paris as pensioners ofthe St. Petersburg Imperial Academy of Arts, these artworks are as unique inthe context of European painting as they are in the history of Russian art. AsAdrienne Childs explains, there are virtually no individual portraits of Blackwomen in European art of the long nineteenth century and the very few exceptions that exist such as Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of a Black Woman(1800) and Frédéric Bazille’s Black Woman with Peonies (1870) only prove thegeneral rule.18 Artists who traveled to the Middle East and North Africa oftenproduced close-up oil, pencil, and watercolor studies of Black figures, whichreflect the “scientific” interest in Black physiognomy and ethnography butresist the traditional categorization of portraiture. In fully developed, finishedpaintings, Black women were almost always relegated to the secondary rolesof servants and slaves, deprived of their individuality and reduced to the status of inanimate props as implied by period commentators often comparingthem to “ebony” and “jet”—decorative luxury commodities or accents thatpunctuate the primary white subjects.19Consequently, Il ia Repin’s Portrait of a Negro Woman (Fig. 3) and VasiliiPolenov’s Egyptian Girl (Fig. 4) departed as much from their European contemporaries as they did from Briullov’s earlier portraits of the Russian aristocracy. One explanation for their unconventional choice of subject matter isthe sheer accessibility of non-European models in Paris, which was not thecase back in Russia. Black people from Africa and the Caribbean, althoughmarginalized, were increasingly part of an international population in theCity of Lights. In addition to being laborers and domestic servants, people ofcolor were also active in the entertainment world as musicians, dancers, circus performers, and artists’ models. Repin and Polenov’s shared studio on theRue Véron was part of an area that included one of Paris’s most concentratedBlack populations. Accordingly, as exotic visualizations of the modern Frenchurban spectacle culture, Black bodies did not only furnish Repin and Polenovwith the opportunity to try their hands at novel and unusual subject matter,17. For a discussion of Russia’s imperial violence, coercion, and ethnic cleansing,see Michael David-Fox, Peter Holquist, and Alexander Martin, eds., Orientalism andEmpire in Russia (Bloomington, 2006); Nicholas B. Breyfogle, Heretics and Colonizers:Forging Russia’s Empire in the South Caucasus (Ithaca, 2005); William C. Fuller, CivilMilitary Conflict in Imperial Russia, 1881–1914 (Princeton, 1985); Eric Lohr, Nationalizingthe Russian Empire: The Campaign Against Enemy Aliens During World War I (Cambridge,Mass., 2003).18. Adrienne L. Childs, “Exceeding Blackness: African women in the art of Jean-LéonGérôme,” in Childs and Libby, Blacks and Blackness in European Art of the Long NineteenthCentury, 125–144.19. Ibid., 141.https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2021.81 Published online by Cambridge University Press

274Slavic ReviewFigure 3. Il’ia Repin, Portrait of a Negro Woman, 1875–76, oil on canvas, 115 x93 cm. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg.Figure 4. Vasilii Polenov, The Egyptian Girl, 1876, oil on canvas, 88.5 x 118 cm.Private Collection.https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2021.81 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Representations of Blackness in 19th-Century Russian Painting275but also provided them with a rare chance to assert their cosmopolitanismand modernity, much like Briullov had done four decades earlier. By the sametoken, given their own peripheral position in the Parisian art world as “foreigners” and “outsiders” who moved almost exclusively in Russian émigrécircles and who sometimes struggled financially and professionally, Repinand Polenov were potentially less beholden to the established formats andrigid self/other binaries governing such depictions.Thus, for example, although the Black female model in Repin’s Portrait ofa Negro Woman is accessorized and inflected with Orientalist accoutrementsand props such as a hookah pipe, discarded Persian slippers, ornate coffeepot, brocaded silk fabrics, and elaborate glistening necklace and pearl earrings, the sitter nonetheless comes across as a confident and dignified individual who commands the viewer’s sustained attention. She does not registeras merely an odalisque or an “Oriental type,” despite Repin’s obvious sensuous delight in rendering the different glimmering surfaces and sumptuoustextures. In his monograph on Repin, Igor Grabar noted that the portraitis rendered with “tremendous human warmth,” while the artist and criticAleksandr Savinov emphasized the model’s psychological presence, writingthat the “Negro woman is a person who palpably possesses an emotional andintellectual life.”20At the same time, the woman’s facial expression is largely inscrutable: isshe sad, lost in thought, indifferent, or bored? It is difficult to tell. This signature impenetrability became a hallmark of French modernist painting as exemplified by Edouard Manet’s infamous barmaid in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère(1882) or the reclining nude in Olympia (1863).21 Unlike the Black servant inthe latter work, however, whose presence functions as a veiled symbolic reference to the white woman’s implied sexual promiscuity, the model in Repin’sportrait does not assume a subordinate role to a central white protagonist,but, on the contrary, entirely replaces the latter as the new, recoded signifierof pervasive ennui and urban, metropolitan modernity.Akin to Repin’s portrait, Polenov’s Egyptian Girl is equally elusive and waslikely inspired by a confluence of different experiences and diverse sources,such as Polenov’s visit to the Egyptian court in the Crystal Palace in London,his exposure to the extensive Egyptian collection in the Louvre, the 1871 premiere of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera, Aida, and a series of contemporary paintingson the subject of ancient Egypt and the Biblical Orient, such as Edward JohnPoynter’s Feeding the Sacred Ibis in the Halls of Karnac (1871) and LawrenceAlma-Tadema’s Joseph, Overseer of Pharaoh’s Granaries (1874). In fact, thereare several striking pictorial parallels between Polenov’s and Alma-Tadema’spaintings. The grainy, textured, impasto surface of the wall, as well as theblue and red floral motifs, the large cut-off ceramic vessel and accompanying20. Igor E. Grabar , Repin, 2 vols. (Moscow, 1963), 1:159; Aleksandr Savinov,“Zametki o kartinakh Repina,” in I[gor]. E. Grabar and I. S. Zil bershtein, eds., Repin:Khudozhestvennoe nasledstvo, 2 vols. (Moscow-Leningrad, 1949), 2:231.21. I would like to extend my thanks to the anonymous peer reviewer of the presentarticle for suggesting this intriguing connection.https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2021.81 Published online by Cambridge University Press

276Slavic Reviewwhite wooden stand on the extreme left hand side of Alma-Tadema’s pictureall seem to have been directly replicated by Polenov.Unlike Repin’s strong, self-assured woman, Polenov’s Egyptian girl seemsto be much more vulnerable and withdrawn. Her facial expression is pensiveand almost melancholic, her posture is guarded and closed-off, and her gazeis demurely averted from the viewer. Although the model is shown topless andwe are given a clear view of her exposed right breast, her shielded posturethwarts a sense of immediate and enticing sexual availability. As in Repin’sportrait, Polenov’s painting is visually opulent and sensuous, combining arich array of bright, saturated colors and glittering surfaces with striking juxtapositions of alternating smooth and rough textures. Overall, however, thereis something foreboding and ominous about this image. It is not clear whothis woman is supposed to be and what her role is in the setting: is she a priestess, a concubine, or a Nubian slave? On the one hand, she wears a luxuriousheaddress and ornate jewelry, on the other, she sits on the floor and appearsto be ill at ease, hemmed in by the ceramic vessels in the foreground. Mostunsettling of all is the sinister-looking bird on her left. Although period commentators mistakenly identified the bird as the sacred Egyptian ibis, it is infact a marabou stork, a scavenging bird of prey.22 With its long phallic beakand drooping folds of fleshy pink skin, the bird seems to hint at sexual predation—an avatar for the absent male master.In contrast to French and English representations of Black women, where,as Childs notes, the subjects’ “black faces [are] often obscured by drapery, ortheir backs [are] turned to the viewer,” so that only “their dark ornamentedbodies activate the scenes,” Repin’s and Polenov’s representations place considerable visual emphasis on the model’s face and, in the case of the EgyptianGirl, attempt to elicit sympathy from the viewer for her plight—a responsetypically reserved for the white female slaves in European depictions.23 Thus,for example, when Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Slave for Sale (1873) was first exhibited in London’s Royal Academy in 1873, the critic E.B. Shuldham comparedthe moving pathos of the beautiful lighter-skinned “Eve” who was tragically“doomed to dishonor” as a concubine in an Oriental harem with “the jet-blackAbyssinian semi-nude [who] sits careless of her fate, whilst a marvelous monkey squats by her side, from the terms of the sale, almost an acknowledgedequal, the monkey and negress evidently going together as one lot.”24 Whilethe white woman is humanized and intended to evoke empathy and pity inthe viewer, the Black woman is marked as degenerate and accepting of herfate, implying that slavery is a condition commensurate with the Black body.There are several possible explanations for Repin and Polenov’s manifest divergences from standard European representations of race. As members of the educated Russian elite who associated with the civic-mindedPeredvizhniki group, they were deeply committed to social causes and to22. I would like to thank Ludmila Piters-Hofmann for her correct identification of thebird as a marabou stork.23. Childs, “Exceeding Blackness,” 14124. E.B. Shuldham, “The Royal Academy,” Dark Blue (1873): 472, quoted in Childs,“Exceeding Blackness,” 136.https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2021.81 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Representations of Blackness in 19th-Century Russian Painting277addressing systemic injustices, as evidenced by a number of their contemporaneous paintings, most notably the Bargehaulers on the Volga (1870–73) andthe Right of the Master (1874). The latter work in particular raises the ominousissue of sexual exploitation and coercion, albeit through a historicizing lens.In fact, in the years immediately preceding the creation of these artworks,thinkers such as Aleksandr Herzen and Nikolai Chernyshevskii had repeatedly compared and condemned the parallel plights of Blacks in America andserfs in Russia. Consequently, Repin and Polenov may have intentionallyembraced the opportunity to represent marginalized Black female subjecthood as a veiled commentary on the persisting inequalities and injusticesfaced by people of color in modern western societies on the one hand, and theRussian peasantry on the other.Perhaps more than any explicit or implicit emancipationist or egalitarian considerations, however, Repin and Polenov were enticed by the creativepossibilities of exploring an entirely new artistic theme and the purely technical challenges that it presented, such as rendering a dark-skinned model ina dimly lit room and capturing the way her Black skin reflected the flickeringlight or created striking coloristic contrasts with her surroundings. Havingtried their hands at a range of different genres in Paris such as history painting, plein air landscape, and contemporary urban scenes, the Russian artistsevidently felt that the ethnic and racial “other” provided a means to both testand assert their own thematic range and artistic capabilities.In his review of the Autumn 1876 Imperial Academy of Arts Exhibition inSt. Petersburg, where both Egyptian Girl and Portrait of a Negro Woman wereshown, the critic Apollon Matushinskii wrote: why [have] these talented artists chosen to depict a black creature in theirpaintings? Which aesthetic thoughts led them to decide to paint an Ethiopianbeauty? It is quite understandable that such a subject can have its place ina painting in order to furnish a superb contrast and augment that which isbeautiful, or quite simply to provide

in Nineteenth-Century Russian Painting Maria Taroutina . baskets of fruit or flowers, and pet animals. Thus, for example, in Karl Briullov's Portrait of Countess Julia Samoilova . 1847-49, watercolor and graphite on paper, 23.7 x 25.9 cm. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Representations of Blackness in 19th-Century Russian Painting 271