Transcription

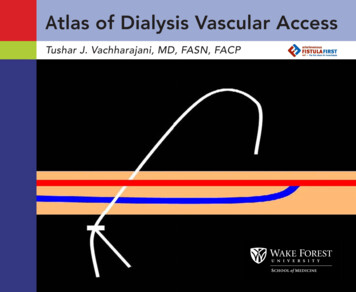

Fibrin sheathAtlas of Dialysis Vascular AccessTushar J. Vachharajani, MD, FASN, FACP

Dedicated to all dialysis patients and hard-working staffCover design – Vipul VachharajaniSchematic representationof arteriovenous fistulaoverlapped by a tunneledcentral venous catheterEditorial Assistance–Amanda Goode, MAResearch Programs Development ManagerDepartment of Internal MedicineWake Forest University School of MedicineMedical Illustration and atlas productionCreative CommunicationsWake Forest University School of Medicinewww.wfubmc.edu/creative 2010 by Tushar J. Vachharajani. All rights reserved

ATLAS OF DIALYSIS VASCULAR ACCESSi

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTSAnatomy of Dialysis Vascular Access . 1Tunneled Catheters . . 13Arteriovenous Fistulas . 28Arteriovenous Grafts . . 53Glossary . 67Bibliography . 68iii

FOREWORDThe old adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” is certainly exemplifiedby Tushar Vachharajani’s Atlas of Dialysis Vascular Access. The Atlas providesa rich source of pictorial information presented in a simple, straightforwardfashion that will have value for the entire patient care team, includingphysicians, nurses, patient care technicians, dieticians and social workers.Jack Work, MDPast PresidentAmerican Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology (ASDIN)iv

PREFACEI have a passion for improving the basic understanding of the dialysis vascular access. A patient’s survivaldepends on proper functioning of this lifeline, yet the dialysis vascular access remains the Achilles’ heel forhemodialysis patients. Unfortunately, because of the myriad medical problems faced by a patient with renalfailure, the dialysis access gets the least amount of attention.The current practice of dialysis treatment in the United States depends heavily on an ancillary staff remotelysupervised by a nephrologist. The training curriculum for physicians provides minimal cross-training indifferent specialties involved in the creation and maintenance of a dialysis vascular access. Moreover, theancillary staffs that provide and supervise the bulk of the care are inadequately trained in the proper handlingof the vascular access.Diagnostic accuracy and active and timely intervention depend heavily on visual clues that are frequentlymissed. There is a need to improve the understanding and visual skills related to the vascular access. The Atlasof Dialysis Vascular Access is a sincere effort in pursuit of this goal. “A picture is worth a thousand words”—acommon adage that can be aptly used to describe this bedside tool for education. Images express a conceptfaster and with greater impact than do pages of textbooks or hours of lectures. This atlas highlights the basicanatomy of the most frequently used vascular accesses and their associated problems. The images have beencollected from patients who have endured the problems and have graciously consented to be photographed.The primary intended audiences for the atlas are physicians involved in dialysis vascular access management,physician extenders, dialysis nurses, patient care technicians, medical students and residents, and clinicaleducators involved in training the future generation of dialysis care providers. I hope that this atlas willultimately lead towards improved quality of vascular access care.I would like to thank the Dialysis Access Group of Wake Forest University School of Medicine (www.dagwfu.com)and its staff (Jean Jordan, RN, Tina Kaufman, RN, Sherry Crawford, RN, Leann Hooker, RN, Wendy Mundy, LPN,Joyce Jackson, PCT, Margaret Bordner, RT-R and Andrea Roark, RT-R) for their assistance with this project. I amgrateful to Health Systems Management, Inc. for providing me with the basic resources needed to collect thepictures. And lastly, I would like to thank my son, Vipul Vachharajani, who spent his valuable high school vacationtime to help me with the cover design and with the atlas layout.Tushar J. Vachharajani, MD, FACP, FASNDialysis Access Group of Wake Forest University School of Medicinev

vi

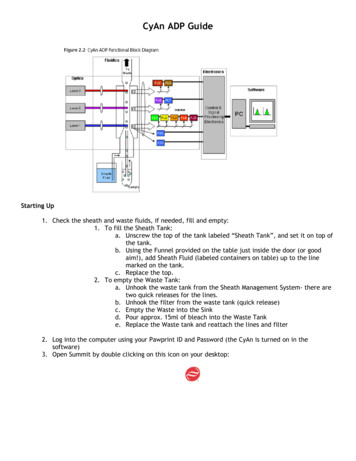

ANATOMY OF DIALYSIS VASCULAR ACCESS A basic understanding of the anatomy of vessels utilized to create the vascular access iscrucial for proper handling and care of an access during dialysis therapy. The venous system of an extremity includes superficial and deep veins. The superficialsystem is most important for access creation. The superficial vein in the upper extremity that is preferred and most commonly utilizedfor arteriovenous fistula creation is the cephalic vein. The radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula at the wrist is the first choice hemodialysis accessand utilizes the forearm segment of the cephalic vein. The brachiocephalic fistula at the elbow utilizes the upper arm segment of the cephalicvein and generally is the second choice site for arteriovenous fistula creation. The other superficial veins in the forearm (the basilic vein on the ulnar side and the medianbasilic vein near the elbow) are occasionally used for arteriovenous fistula creation. The deep veins in the forearm are not ideal for arteriovenous fistula creation. The deep veinsin the upper arm are the brachial and basilic veins that run parallel to the brachial artery. The basilic vein in the medial aspect of the upper arm is the most common deep veinutilized for arteriovenous fistula creation. The basilic vein is mobilized from its usuallocation and transposed superficially through the deep fascia in the upper arm to createthe “transposed basilic vein” arteriovenous fistula. The brachial veins in the upper arm are used for dialysis access as a last resort. The brachialveins and the basilic vein join and continue as the axillary vein until the outer border of thefirst rib. The axillary vein continues as subclavian vein from the outer border of the first riband extends to the sternal end of the clavicle. A graft made from synthetic material like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is utilized fordialysis access creation if the native vessels are not suitable for creating an arteriovenousfistula. The forearm loop, upper arm straight and thigh loop grafts are commonly utilizedconfigurations for creating a dialysis access.1

Anatomy of Upper Extremity VesselsSubclavian v.Internal jugular v.Cephalic archsegmentCarotid a.DELTOIDAxillary v.Brachial v.Upper armcephalic v.BICEPSBasilic v.Brachial a.Forearmcephalic v.Radial a.Ulnar a.Palmar arch2

Radiocephalic Arteriovenous Fistula (Brescia-Cimino)3

Snuff-box Arteriovenous FistulaEnd-to-sideanastamosisForearmcephalic veinRadial a.4

Proximal Forearm Arteriovenous FistulaAnastomosis betweenperforating branchand proximal radial arteryCephalic v.Brachial a.Radial a.Proximalperforatingbranch5

Proximal Forearm Arteriovenous FistulaAnastomosis betweenproximal radial arteryand median antecubital veinBasilic v.Cephalic v.Brachial a.Medianantecubital v.Radial a.6

Brachiocephalic Arteriovenous FistulaAnatomoses betweenperforating branchand proximal radial artery7

Transposed Basilic Vein Arteriovenous FistulaCephalic v.Inset: “swing point”depicting the basilicvein mobilization fromthe deeper location tothe superficial tunnelBasilic v.BICEPSEnd-to-sideanastamosisBrachial a.8

Forearm Loop Arteriovenous Graft9

Upper Arm Arteriovenous GraftCephalic v.Axillary v.End-to-sideanastamosis10

Thigh Arteriovenous GraftExternaliliac a.Femoral a.Femoral v.11

The catheter is placed inthe right internal jugularvein with a smooth curve inthe subcutaneous tunnel.The tip of the catheter isplaced in the right atriumto achieve adequate bloodflow during hemodialysis.12

TUNNELED CATHETERSTunneled central vein catheters are often used as temporary accesses for hemodialysis. Tunneledcatheters can be placed at several sites. The preferred site is the right internal jugular vein.Other sites often used are the left internal jugular vein and femoral vein. Subclavian vein isaccessed only if the possibility of placing an ipsilateral permanent arteriovenous access in theupper extremity is unavailable. The risk of developing central vein stenosis is very high with asubclavian vein catheter.Rarely, tunneled catheters are placed in the inferior vena cava through a translumbar ortranshepatic approach.Potential complications of a tunneled catheter are: Malfunction due to mechanical causes like– Poor placement technique– Retraction with or without exposure of the cuff– Cracked hub or broken clamps– Thrombosis/Fibrin sheath formation Infection– Exit site– Tunnel infection Central vein stenosisEarly recognition of these complications is important to prevent: Loss of the vascular site if the catheter falls out Inadequate dialysis clearance Bacteremia- and sepsis-related morbidity and mortalityThe photographs in this chapter provide adequate tools to enable dialysis access physiciansand staff to recognize and identify common problems associated with tunneled catheters.13

Left-sided CatheterActual left internal jugular veintunneled catheter removedfrom a patient showing multipleangulations along its course.The complex anatomical pathway traversed by left internaljugular vein catheters may beresponsible for higher incidence of catheter malfunctionand thrombosis.A: Schematic representation ofthe angulations caused bythe left internal jugular vein,left brachiocephalic veinand superior vena cava.ABB: Schematic representation ofthe additional angulation,as the catheter traversesthe mediastinum and is notvisualized on frontal projection radiograph.Computer generated figures designed by Vipul Vachharajani14

Right-sided CatheterActual right internal jugular veintunneled catheter removed froma patient showing a single smoothcurve.A: Schematic representation of thesmooth curveB: Cross-sectional schematic representation of the smooth curveABComputer generated figures designed by Vipul Vachharajani15

Kinked CatheterThe catheter in thesubcutaneous tunnel isacutely kinked causingmechanical obstructionto the blood flow.16

Malpositioned Tip of CatheterLeft internal jugular catheterwith kink in the subcutaneous tunnel (arrow). The tip isplaced in the left innominate(brachiocephalic) vein.Catheter tipThe catheter is unlikely toprovide adequate bloodflows for dialysis.17

Malpositioned Tip of CatheterTesio catheter with malpositionedtips. Catheter tips are in the proximal superior vena cava.Catheter tipCatheter tip18

Catheter Tip Retraction7th rib7th ribThe catheter tip often retracts from a supine to an erect position, especially if it is anchored onbreast or pectoral fat. Thus, the tip of the catheter should be placed in the right atrium.19

Catheter Tip in Azygos VeinABCathetertipA: The tip of the left internal jugular catheter is placed in the azygos vein. Anacute angle curve is noted with twisting of the catheter at the junction of thesuperior vena cava and azygos vein.20B: The catheter tip has been repositioned inthe right atrium.

Fibrin Sheath FormationABFibrin sheath develops around the catheter. The sheath acts like a one-way valve and preventsadequate and free pulling of blood through the catheter. The fibrin sheath can be disruptedeither with an angioplasty or can be stripped using a snare device. The pre-angioplasty imageabove (A) shows poor filling of the right atrium and the contour of the catheter is maintainedbeyond the catheter tip. Post-angioplasty image above (B) shows the contrast flowing freelyin to right atrium. The fibrin sheath can extend from the cuff to beyond the catheter tip.21

Fibrin sheathAn intact fibrin sheath pulledout along with the catheter.A fibrin sheath is a flimsyfibroepithelial tissue thatextends from the cuff (A) tothe tip of the catheter (B).AB22

Intraluminal ThrombusAFibrin sheath extendingbeyond the tip of thecatheter and occluding itcompletely.BAn organized thrombusoccluding the tip of thecatheter.CThe organized clot hasbeen extruded from thecatheter.23

Split Tip catheterA split tip tunneled catheter placed in the left internal jugular vein. Thearterial tip is curled up(arrowheads) and kinkedleading to high dialysisarterial pressures andpoor delivery of bloodflow during dialysis.24

Exposed CuffABA: The cuff of the catheter is exposedat the exit site. The exit site shouldbe evaluated prior to each dialysis session. A catheter with an exposed cuff can be easily pulledout and can lead to loss of a vitalvascular access site. The exposedcatheter cuff would also suggestthat the tip is no longer at theproper location and delivery ofblood through this catheter maynot be adequate. The replacement of the catheter over a guidewire can be easily performed withproper anchoring and the patientcan return for dialysis therapy onthe same day.B: Disrupted subcutaneous tunnel(arrowheads) with exposed catheter cuff at the exit site.25

Exit Site InfectionExit site erythema with crustingsuggestive of infection or allergicreaction to topical ointment ortape. The exit site should beevaluated prior to every dialysistherapy for early signs of infection.The exit site infection can spreadthrough the subcutaneous tunnelcausing bacteremia, sepsis andworsening morbidity and mortality.26

Tunnel InfectionAA: Purulent fluid collection under thedressing suggestive of infection.BB: Purulent secretion, erythema over thetunnel and skin changes secondary toinfection in the subcutaneous tunnel.The catheter must be removed promptlyfor effective antibiotic therapy and morbidity reduction.27

ARTERIOVENOUS FISTULAArteriovenous fistula (AVF) is the preferred dialysis access because of a lower incidenceof associated morbidity and mortality. An AVF is surgically created by connecting theartery and vein. Approximately 8-12 weeks are required for an AVF to mature completely.The sites available for creating an AVF are limited, requiring proper handling and careduring hemodialysis therapy.The common problems associated with an AVF are: Poor or delayed maturation Infiltration and hematoma formation during hemodialysis secondary to impropercannulation technique Stenosis at the “swing site,” the segment of the vein mobilized for arterial anastomosisin the creation of an arteriovenous fistula Stenosis due to neo-intimal hyperplasia, eventually leading to thrombosis Aneurysmal dilatation either due to vessel trauma from frequent needle puncturesand/or a proximal stenosis Infection Steal syndrome due to ischemia of the distal extremity High output congestive heart failure from large arteriovenous fistula Central vein stenosisMany of these problems can be prevented with proper cannulation techniques andregular monitoring and surveillance during hemodialysis therapy. Early diagnosis andtimely referral requires understanding and recognizing the pathology.28

The current chapter provides visual aids to commonly seen pathology related toarteriovenous fistulas and some of the endovascular interventions that can help maintaintheir patency. The chapter opens with photographs showing normal vasculature suitablefor creating an AVF. Ideally, an AVF should be created early enough to allow the AVFto mature and avoid the need to place a central venous catheter for dialysis therapy.The preservation of vessels in chronic kidney disease patients is the key to creating afunctional AVF.The remaining images highlight some of the common problems encountered in a busyhemodialysis clinic.29

Well-preserved Forearm VeinsWell-preserved veins in the forearm and upper arm for creating a functional arteriovenous fistula. Vessel preservation is essential in chronic kidney disease patients.30

Well-preserved Upper Arm Cephalic VeinAvoiding venipuncture in the forearm and elbow and refraining from placingperipherally introduced central catheters (PICC) are two methods to preserve veins.31

Snuff-box AVFThe anastomosis is generally distal to the wrist joint in the snuff-box.32

Radiocephalic AVFA normal radiocephalic fistula with the anastomosis proximal to the wrist joint.33

Transposed Forearm Basilic Vein AVFThe forearm basilic vein istransposed to create a radiobasilic vein AVF.The forearm basilic vein (markedby arrows) is transposed to thevolar surface of the forearm andanastomosed to the radial arteryat the wrist.34

Transposed Forearm Cephalic Vein AVFThe forearm cephalic vein (marked by arrows) is transposed to create a loop configurationand anastomosed to the brachial artery at the elbow.35

Proximal Forearm AVFA fistulogram highlighting proximalforearm AV fistula. Gracz et al in 1977described the proximal forearmarteriovenous fistula involving anend-to-side anastomosis betweena perforating branch of the cephalicor median antecubital vein and theproximal radial artery. Subsequentlyseveral modifications have beendescribed by Bender et al and Kroneret al creating a native fistula utilizingthe deep venous system in theforearm and either the proximalradial or brachial artery. The proximalforearm fistula is a valuable additionalsite for native vascular access forhemodialysis before considering anupper arm access.UlnaboneRadiusboneUlnar a.Radial a.Cephalic v.Proximal forearmanastomosis36

Upper Arm AVFTransposed BasilicVein AVFA normal transposed basilic veinarteriovenous fistula showingthe scar extending from theaxilla to the elbow on the medialaspect of the upper arm.Brachiocephalic AVFA normal brachiocephalic fistulawith a horizontal scar at the elbow.37

Massive InfiltrationEighty-year-old patient who hada functioning right brachiocephalic fistula placed well beforethe need for dialysis. Unfortunately during his first treatmentthe fistula infiltrated due to improper cannulation techniqueresulting in a large hematomaalmost encircling his upper arm.Fortunately for the patient thefistula was still functional and after 4 weeks of rest to the armthe hematoma resolved completely and the access could beused for dialysis.38

Complication of PICC LineA fistulogram performed on anon-maturing brachiocephalicfistula. The entire cephalic veinsegment in the upper arm wassmall and sclerosed secondaryto a previous placement of aperipherally introduced centralcatheter (PICC). The devastating results of a PICC line can beclearly appreciated in this case.39

“Swing site” StenosisABCRadialarteryStenosedforearmbasilic veinWristThe fistulogram showing a long inflow segment stenosis which was successfully balloonangioplastied. A: Pre-angioplasty. B: Waist on the balloon. C: Post-angioplasty image.Thirty-five-year-old patient with a forearm basilic vein to radial artery fistula. The forearmbasilic vein was mobilized surgically leading to significant stenosis in the “swing site.”The patient presented with inability to achieve prescribed blood flows during dialysis andwith high dialysis arterial pressures. On physical examination the inflow augmentation waspoor with a very weak pulse and bruit.40

ABCDA: Transposed basilic vein AVF with a tight stenosis at the “swing site” (arrowhead). B: Waist onthe balloon shown during percutaneous angioplasty. C: Complete resolution of the stenosis.D: Recurrence of the stenosis 4 months later.A “swing site” stenosis typically presents as a highly pulsatile fistula with a high pitched bruiton physical examination. The dialysis venous pressures are recorded to be high and often thepatient continues to bleed for a prolonged period of time once the needle is withdrawn postdialysis therapy.41

AneurysmBrachiocephalic fistula with ananeurysm at the arterial anastomotic site. The aneurysmhas a tight, shiny skin. The patientneeds to be referred for an urgentsurgical evaluation before acatastrophic event occurs.42

Mushroom-shaped AneurysmABC86-year-old female with a large“mushroom”-shaped aneurysm atthe anastomosis in a brachiocephalicfistula. The aneurysm measuresapproximately 8cm x 6cm with a shinyand tense-appearing superficial skin.An aneurysm needs to be monitoredon a regular basis to avoid reaching asize as seen in this patient. As perK/DOQI guidelines the patient withan aneurysm 1.5 to 2 times the nativevein should be referred for surgicalevaluation and monitored at frequentintervals for any changes.43

Steal syndrome87-year-old female with a brachiocephalic fistula created approximately9 months prior to photograph whocomplained of pain and numbnessover her right hand during dialysis.On examination the fingers wereblue and cold (A). Panel B compares the color of her hand to anormal pink color.Upper arm fistulae are more likelyto cause ischemic symptoms compared to forearm fistulae. The presence of poor peripheral vasculaturesecondary to diabetes, calcificationand peripheral arterial disease is theprimary etiological factor. A salvagesurgical procedure can sometimesbe attempted. This patient had extensive peripheral arterial diseaserequiring ligation of the fistula topreserve distal circulation.44AB

HematomaBC61-year-old female with a recentlyplaced left radiocephalic fistula,developed a large hematoma sevendays after the surgery. Patientswith chronic kidney disease havean increased tendency to bleed,especially if they are taking additionalanti-platelet agents such as aspirinor clopidrogel or are being anticoagulated with warfarin.Development of a large hematomaand easy bruising is frequently observedin the dialysis population.45

Hematoma73-year-old female patient witha recent surgical revision of brachiocephalic fistula presentedwith an acute golf ball sizedhematoma and a slow leakingpseudoaneurysm. The steristripswere partially supporting the gaping surgical wound. The patient wasreferred to the vascular surgeon foremergent ligation.46

Central Vein StenosisABCSixty-seven-year-old man who presented with left upper arm swelling. He had a transposed basilicvein fistula placed about 18 monthsprior to photograph. He also hada history of several central venouscatheters. On examination, he hadprominent collateral veins on hisshoulder and chest wall (Panel A).The forearm and hand were swollen significantly (B).A fistulogram revealed a 70% stenosis at the “swing site” and 80%stenosis in the left subclavian veinaccounting for the collateral veinson the chest wall. The patient wastreated successfully with percutaneous angioplasty.47

Skin Rash45-year-old male who recently started hemodialysis developed anallergic reaction to betadine. The rash as seen above was erythematousand maculo-papular in nature. The patient complained of severe itchingand required therapy with anti-histaminic medications.Allergic reaction to betadine, iodine, antibiotic cream and tape are notuncommon and need to be well documented in the patient’s chart forfuture reference.48

Stable AneurysmC36-year-old man with a right brachiocephalic fistula created in 2004. Thefistula has several small aneurysms which have been stable. The overlyingskin is intact without any change in pigmentation. The fistula did nothave any evidence of outflow obstruction on physical examination. Acentral vein stenosis was ruled out on fistulogram. The fistula needs to bemonitored and patient was educated to inform about any increase in sizeor skin changes. The fistula size should be measured and documented inthe medical records for future reference.49

Arm Elevation TestASeventy-four-year-old male with a radiocephalic fistulacreated in 2007. Panel A shows the fullness (arrow)near the anastomosis due a small aneurysm.The fullness collapses completely on arm elevation(Panel B, arrow) suggesting an absence of significantoutflow obstruction. A simple bedside examination thatneeds to be performed prior to every dialysis session.50B

Red Hand SyndromeCTwenty-four-year-old male with a radiocephalic fistula that was createdin 2007. The patient presented after having noticed increased swelling,warmth and difficulty cannulating during dialysis. On examination theforearm and hand were swollen and erythematous. A bruit was hearddistal to the fistula. The patient was treated with antibiotics for cellulitis.The arm remained swollen even after the resolution of cellulitis.A fistulogram revealed multiple collateral veins without any significantoutflow stenosis with increased distal blood flow causing “red hand”syndrome from venous stasis. The patient was sent for surgical ligationof multiple collateral veins, which resulted in complete resolution of hissymptoms. The fistula was salvaged.51

Central Vein StenosisAA: Massively swollen right upper extremity from completely occluded right subclavian vein. The transposedbasilic vein arteriovenous fistula is patent.52BB: Extensive network of collateralveins over the right shoulderand chest area.

ARTERIOVENOUS GRAFTSArteriovenous grafts (AVG) are used for patients who do not have adequate native veinsfor creating a fistula. An AVG is the second best option for hemodialysis.Several sites are used for AVG placement. Forearm loop AVG is the most common.Upper arm grafts are generally placed as a straight connection between the brachialartery and the basilic or axillary vein. A thigh AVG is generally a last resort when all otheroptions in the upper torso are unavailable due to variety of reasons.AVG are rarely placed across the chest wall, connecting the axillary artery and axillaryvein or axillary artery and a suitable vein on the opposite site. AVG have also been rarelyconnected to the right atrial appendage.The common problems associated with an AVG are: Venous anastomotic stenosis from neo-intimal hyperplasia Development of pseudoaneurysms Thrombosis Infection Central vein stenosis, especially with history of multiple central venous cathetersUsing a tourniquet is not required while cannulating a graft but it is absolutely essentialfor an AVF.The current chapter highlights some of the common problems associated with an AVG.53

Tourniquet UseABUsing a tourniquet is an absolute must for an arteriovenous fistula (Panel A), which is notrequired for an arteriovenous graft (B).54

Forearm Loop Arteriovenous GraftA normal forearm loop arteriovenous graft.55

Upper Arm AVGA normal upper arm arteriovenous graft.56

Thigh AVGBAFemurA. Arteriogram showing the patent arteriovenousgraft in the thigh.B. A normal thigh arteriovenous graft being usedfor dialysis.Photo courtesy of Jack Work, MD57

PseudoaneurysmDevelopment of pseudoaneurysmsover time in an arteriovenous graftis not uncommon. The pseudoaneurysms develop at frequentlypunctured sites and may worsen inthe presence of proximal stenosis.The needle puncture sites shouldbe rotated to minimize this complication. Smaller pseudoaneurysmscan be treated endovascularly witha covered stent as along as it doesnot compromise the cannulationsegment, as shown in the nextimage. Larger pseudoaneurysmsneed to be treated surgically.Pseudoaneurysms tend to developclots and can lead to thrombosisof the access. The risk of bleedingis higher if the pseudoaneurysm iscannulated for dialysis.58

ABSmaller pseudoaneurysms withsuperficial skin changes can be atan increased risk of rupture andbleeding. Panel A shows multiplepseudoaneurysms in a patient withsignificant skin changes. Due tomultiple medical problems she wasa high risk for surgical interventionand hence an endovascular procedure was performed.Patient underwent an endovascularprocedure involving a deploymentof a covered stent (B) resulting insalvaging the graft and preventing the pseudoaneurysms fromexpanding further.A covered stent is a stent coatedwith PTFE-like material making itsuitable for cannulation during dialysis, if absolutely necessary.59

Multiple Arteriovenous GraftsEighty-six-year-old female with a failed forearm loop AVG (inner loop). A newAVG was placed successfully, utilizing the same arterial inflow and venous outflowanastomosis (outer loop). Using a long forearm loop of PTFE can increase therisk of thrombosis due to increased resistance, but fortunately this patient hashad a functioning access one year after surgery.60

“Sleeves Up” Examination“Sleeves Up” Examination for every AVG:All patients with forearm AVGs should have a routine “sleeves up” examination ofthe upper arm as seen in this patient. The upper arm cephalic vein (arrow heads) isnicely developed and can be utilized for future conversion to a secondary arteriovenous fistula.61

Central Vein StenosisForty-five-year-old male with a right forearm loop AVG placed in 2003 has markedcentral vein stenosis. The collateral veins are visualized on his shoulder and chest(arrowheads).The patient has a right subclavian vein stent with recurrent stenosis as shown innext image.62

Central VenogramABA: Intrastent stenosis (arrowhead) B: Waist on the balloon used forin the right subclavian vein.angioplasty.CC: Post-angioplasty completeresolution of the stenosis.63

Venous Outflow StenosisABNinety-three-year-old male with a left upper arm straight AVG with classic venous outflowstenosis. The patient was referred for a fistulogram based on clinical findings of pulsatilecharacter to AVG and prolonged bleeding (more than 30 min.) following dialysis needlewithdrawal.An 8cm long segment of stenosis extending from the graft in to the axillary vein was notedon fistulogram (arrowheads in Panel A). The stenosis was successfully angioplastied usingan 8mm balloon without any residual stenosis (B).64

Pseudoaneurysm65-year-old female patient presentedwith left upper arm AVG with largepseudoaneurysms measuring 4cmin diameter. The aneurysms are closeto the arterial anastomosis and werebeing frequently punctured fo

of the vascular access. Diagnostic accuracy and active and timely intervention depend heavily on visual clues that are frequently missed. There is a need to improve the understanding and visual skills related to the vascular access. The Atlas of Dialysis Vascular Access is a sincere effort in pursuit of this goal.