Transcription

ANCCNCPD 2.0Contact HourProfessional Case ManagementVol. 27, No. 2, 58-66Copyright 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.Impact of the Registered Nurse ClinicalLiaison Role in Ambulatory Care onTransitions of CareA Retrospective Cohort StudyMollie J. Flynn, BSN, RN, Beckie J. Kronebusch, MS, APRN, CNS, Laura A. Sikkink, MSN, RN,Kristi M. Swanson, MS, Kelly J. Niccum, CCRP, PMP, Sarah J. Crane, MD, Bernard Aoun, MD, andPaul Y. Takahashi, MDABSTRACTPurpose of Study: To determine the relationship between engagement with the novel register nurse careliaison (RNCL) and enrollment in care management compared with usual care in hospitalized patients.Primary Practice Setting: Patients in the hospital from January 1, 2019, to September 30, 2019, who wouldbe eligible for care management.Methodology and Sample: This was a retrospective cohort study. The authors compared a group of 419patients who utilized the services of the RNCL at any time during their hospital stay with the RNCL to apropensity matched control group of 833 patients, which consisted of patients who were hospitalized duringthe same time as the RNCL intervention group. Our primary outcome was enrollment in care managementprograms. Our secondary outcome was 30-day readmissions, emergency department (ED) use, and office visits.The authors compared baseline characteristics and outcomes across groups using Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitneyand χ2 tests and performed an adjusted analysis using conditional logistic regression models controlling forpatient education and previous health care utilization.Results: The authors matched 419 patients who had engaged an RNCL to 833 patients in the usual caregroup; this comprised the analytic cohort for this study. The authors found 67.1% of patients enrolled in a caremanagement program with RNCL compared with only 15.3% in usual care (p .0001). The authors foundhigher rates of enrollment in all programs of care management. After the full adjustment, the odds ratio forenrollment in any program was 13.7 (95% confidence interval: 9.3, 20.2) for RNCL compared with usual care.There was no difference between groups with 30-day hospitalization or ED visit.Conclusion: In this matched study of 419 patients with RNCL engagement, the authors found significantlyhigher enrollment in all care management programs.Implications for Case Management Practice: These findings encourage further study of this care model. Thiscould help enhance enrollment in care management programs, increase relationships between inpatient practiceand ambulatory practice, as well as increase communication across the continuum of care.Key words: care transitions, discharge, liaison, primary care, registered nursePa tients experience multiple chronic conditionscommonly in the Unites States, with over 25%of the population suffering two or more chronicconditions (Ward et al., 2014). Health systems cancare for the highest risk patients using care management programs, which focus either on individual conditions like heart failure or through a comprehensiveapproach for multiple illnesses (Leppin et al., 2014).There are examples of care transition models in theliterature. In the transitions coach model, a healthcoach helps patients who were recently dischargedfrom the hospital and provides tools and support toencourage patients to be involved in their transitionof care (Coleman et al., 2006). In a second model58Professional Case Managementan advanced practice nurse evaluates high-risk eldersin the home setting post-discharge, which has beenshown to decrease rehospitalizations and health carecosts (Naylor et al., 2004). Additionally, Hollandet al. (2019) discuss the collaborative approach ofa community care team, utilizing a nurse care coordinator and case manager to assist individuals inAddress correspondence to Mollie J. Flynn, BSN, RN,Department of Nursing, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW,Rochester, MN 55905 (Flynn.mollie@mayo.edu).The authors report no conflicts of interest.DOI: 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000538Vol. 27/No. 2Copyright 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

navigating the health care system. Further evidencediscusses telephone follow-up by nursing, someincluding specific face-to-face meetings prior to discharge and subsequent call, that can reduce readmissions, but without accepted best practice, it is difficult to direct case management practices (Reese et al.,2019; Vergara et al., 2018; 2020).Although the authors recognize the potential importance of these care management programs described,patients often face barriers to enrollment and, thus, donot always participate in these programs. Mayo ClinicRochester has many primary care programs and resourcesoutlined in a previous article (Flynn et al., 2021).Due to the importance of these programs, hospitals often try to promote enrollment using various resources. The primary care social worker oftenassesses patients for behavioral or psychosocial needs,connects patients to community resources, and coordinates services (Lombardi et al., 2019). The hospital social worker has a similar job description, withthe addition of discharge planning efforts (Grant &Toh, 2017). Mayo Clinic hospital case managers helpwith discharge planning as well and review medicalnecessity of interventions and hospital stay, based oninsurance guidelines (Kelly et al., 2019). Mayo ClinicRochester created a new role for a register nursecare liaison (RNCL). This registered nurse works tobridge both the hospital and the primary care clinicto help facilitate enrollment in specialized programsas needed (Flynn et al., 2021). The primary aim ofthis study was to determine the relationship betweenengagement with the RNCL and care managementprogram enrollment compared with usual care ina propensity matched group of hospitalized adultpatients. Propensity score matching of two treatmentgroups is a technique used to remove confoundingbias in a nonrandomized study. As a secondary aim,the authors sought to determine the relationshipbetween RNCL engagement and 30-day hospitalization or 30-day emergency department (ED) visitscompared with usual care.MethodsDesign and SettingThis was a retrospective cohort study of patients whoengaged the services of the RNCL versus a propensitymatched control group of patients who did not. Thisstudy was conducted within primary care in Rochester, Minnesota, and included patients who weredischarged from the hospital from January 2019to September 2019. The study was reviewed andapproved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional ReviewBoard. The study adhered to the principle of the Declaration of Helsinki.PopulationAll patients who utilized the services of the RNCL atany time during their hospital stay were included inthe RNCL intervention group. Inclusion criteria forRNCL services included patients who had a primarycare provider at Rochester, Mayo Clinic primarycare, living near Rochester, Minnesota, and beinghospitalized at a Mayo Clinic hospital. Patients alsomust have had an Elder Risk Assessment (ERA) scoreover 16, which placed them at risk for hospitalization. The ERA accounts for comorbid health burdenand previous hospital utilization and a score over 16places an individual in the top 10% for risk of hospitalization (Crane, et al., 2010). Finally, patients wereeligible if they had a LACE score (length of stay[L], acuity of admission [A], comorbidity [C], andemergency department utilization in the 6 monthsbefore admission [E]) greater than 59 and possesseda high risk for readmission, like chronic obstructivepulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure, and sepsis (Iyngkaran et al., 2018; Krumholz et al., 2016;van Walraven et al., 2012; Wallace et al., 2019).The exclusion criteria comprised refusal for medicalrecord review, having a primary care provider outside of Mayo Clinic primary care, as well as obstetrical and psychiatric admissions.The propensity matched control group includedpatients who were hospitalized during the sameperiod as the RNCL intervention group. Eligible controls must have been 18 years or older at the timeof hospital discharge, with a LACE score greaterthan 59, and admitted to the same hospital servicesand department units as those in the RNCL intervention group. Patients who did not consent to havetheir medical records used for research purposes wereexcluded from the pool of eligible controls. The control group was propensity matched at a ratio of 1:2cases to controls based on age, sex, ethnicity, race,language, marital status, chronic health conditions(as measured by the Charlson comorbidity index)and LACE score, as well as the length of stay ofthe index hospitalization and the hospital service anddepartment unit they were admitted to. Age, sex,ethnicity, race, language and marital status, LACE score, and the characteristics of the index hospitalization were electronically abstracted from the electronic medical record. Comorbid health conditionswere determined using International Classification ofDiseases, Ninth Revision and Tenth Revision (ICD-9and ICD-10) billing codes and the Deyo adaptationof the Charlson comorbidity index. The patients inthe control group included those patients who metcriteria for enrollment but were not enrolled. Themain reason is that a single RNCL cannot meet thevolume of hospitalized primary care patients.Vol. 27/No. 2Professional Case Management 59Copyright 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

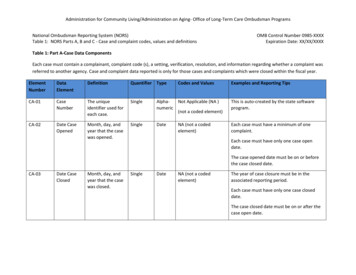

InterventionPredictorsReferrals to care management programs in the studywere done in two primary ways. A full methodologyof the intervention has been previously reported. Thisincludes a detailed description about the role, caremanagement programs, and the RNCL process forreviewing, seeing, and referring patients to care management programs. “The RNCL model of care provides enhanced services and care for a vulnerable population at risk for future health decline. The ongoinggoal is to ensure patients can enroll in ambulatory caremanagement programs and receive appropriate care atthe opportune time” (Flynn et al., 2021, pp. 130–131).As the first method of referral, the RNCL reviewed alist within the electronic medical record daily. Thelist included a cohort of all hospitalized primary carepatients older than 18 years except patients who werehospitalized for obstetric or psychiatric reasons. TheRNCL stratified patients based on the LACE scoreand the ERA to pinpoint the highest risk patients(Crane et al., 2010; van Walraven et al., 2012). Withinthe high-risk strata, the RNCL found patients withhigher risk diagnoses including congestive heart failure, COPD, sepsis, or diabetes. The second way toreceive referrals was from direct communication to theRNCL from either the hospital or ambulatory providers. This was usually done by a phone call or messagesent via the electronic health record.After identifying high-risk patients, the RNCLwould determine patient qualifications for programs.The RNCL would then see the patient or family atthe bedside to explain the options and offer enrollment to the primary care program. The RNCL wasable to set up initial home visit consults for MayoClinic Care Transitions (MCCT) or get a specialtyclinic visit scheduled prior to the patient leaving thehospital. Pertinent insight on discharge plans or primary care interventions were shared with both inpatient and primary care team members.In addition to the propensity matched predictors, theauthors included measures of prior utilization as apotential covariate for adjustment in outcome models. These utilization measures included the numberof hospitalizations and the number of ED visits thatoccurred in the 12 months prior to the index hospitalization. These measures were obtained using theelectronic medical record. The authors also includededucational level as an adjustment factor, whichwas obtained from the most recent patient-providedinformation form on file.OutcomesThe primary outcome was coordination of servicesfollowing hospital dismissal. These services includedthe following: enrollment in MCCT, enrollment inAdult Care Coordination (ACC), enrollment in palliative care homebound program, enrollment in primary care house calls program, and referral to integrated community specialists (ICSs) (specialty care).For secondary outcomes and for hypothesis generation, the authors also evaluated 30-day hospital readmissions and ED visits, both overall did not lead tohospitalization. The authors further assessed whetherpatients were evaluated in the outpatient setting inthe month following hospital dismissal.60Professional Case ManagementAnalysisThe authors described both the entire cohort and thecharacteristics of the matched cohort. The authorscompared these characteristics between RNCL intervention and control groups using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables and theχ2 test for categorical measures. Crude rates of the primary and secondary outcomes were compared amongthe matched cohort using χ2 tests. A p value less than.05 was deemed to be statistically significant. Theauthors performed an adjusted analysis of primary andsecondary outcomes using multivariable conditionallogistic regression models controlling for prior hospital utilization, prior ED utilization, and educationallevel. Data management and statistical analyses werecarried out using SAS 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina).ResultsA total of 539 patients were identified who had initialengagement with the RNCL intervention during thedefined study period. Of this number, 101 patientswere excluded based on study inclusion and exclusion criteria, leaving 438 patients in the RNCL intervention arm to be matched. A pool of 7,311 controlsubjects was identified that met study inclusion criteria. A total of 419 patients from the RNCL intervention group were able to be propensity matchedto a total of 833 control subjects. The characteristicsof the full study population, as well as the matchedcohort, are described in Table 1.In comparing the full study population ofpatients who interacted with the RNCL to the poolof control subjects, the authors found significant differences in baseline characteristics prior to propensitymatching. The intervention group was older with anaverage age of 73.8 years (SD: 16.2). They were morelikely to be female, 90% were White and 54.8% wereunmarried, and more likely to be unmarried. Theyalso were more likely to suffer history of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheralvascular disease, stroke, dementia, COPD, diabetes,Vol. 27/No. 2Copyright 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

TABLE 1Cohort CharacteristicsFull CohortMatched CohortCases (n 438)Control (n 7,311)p ValueCases (n 419)Control (n 833)p Value73.8 (16.2)70.3 (15.6) .000173.5 (16.3)73 (15.1).2954Female225 (51.4)3,162 (43.2)217 (51.8)417 (50.1)Male213 (48.6)4,149 (56.8)202 (48.2)416 (49.9)6,750 (92.3)376 (89.7)749 (89.9)CharacteristicAge, M (SD)Sex.0009Race.5634.0295.9600White394 (90)African12 (2.7)145 (2)12 (2.9)26 (3.1)Asian12 (2.7)88 (1.2)12 (2.9)25 (3)Other/unknown20 (4.6)328 (4.5)19 (4.5)33 (4)EthnicityHispanicNot HispanicUnknown.6694.952911 (2.5)162 (2.2)11 (2.6)24 (2.9)419 (95.7)6,971 (95.3)401 (95.7)794 (95.3)8 (1.8)178 (2.4)7 (1.7)15 (1.8)Language.1116.9292*English416 (95)7,078 (96.8)397 (94.7)787 (94.5)Other20 (4.6)213 (2.9)20 (4.8)43 (5.2)2 (0.5)20 (0.3)2 (0.5)3 (0.4)UnknownMarital StatusMarried.6563* .0001195 (44.5)4,179 (57.2)187 (44.6)Unknown3 (0.7)132 (1.8)3 (0.7)375 (45)3 (0.4)Unmarried240 (54.8)3,000 (41)229 (54.7)455 (54.6)History of MI73 (16.7)788 (10.8).000171 (16.9)129 (15.5).5061History of CHF180 (41.1)2,088 (28.6) .0001174 (41.5)332 (39.9).5695History of peripheral vascular disease195 (44.5)2,223 (30.4) .0001181 (43.2)379 (45.5).4399History of cerebrovascular disease120 (27.4)1,066 (14.6) .0001114 (27.2)245 (29.4).4158History of dementia59 (13.5)418 (5.7) .000157 (13.6)119 (14.3).7432History of COPD163 (37.2)1820 (24.9) .0001155 (37)299 (35.9).7028History of ulcer17 (3.9)209 (2.9).216717 (4.1)36 (4.3).8264History of mild liver disease41 (9.4)682 (9.3).982036 (8.6)78 (9.4).6542History of diabetes157 (35.8)2,037 (27.9).0003151 (36)293 (35.2).7630History of diabetes with organ damage122 (27.9)1236 (16.9) .0001118 (28.2)229 (27.5).802322 (5)153 (2.1) .000122 (5.3)47 (5.6).7744173 (39.5)2,031 (27.8) .0001165 (39.4)315 (37.8).5911History of hemiplegiaHistory of moderate/severe renal diseaseHistory of moderate/severe liver disease13 (3)233 (3.2).799612 (2.9)28 (3.4).6368History of metastatic solid tumor19 (4.3)424 (5.8).200617 (4.1)33 (4).9350History of aids1 (0.2)12 (0.2).74991 (0.2)3 (0.4).7193.5156History of rheumatologic disease52 (11.9)525 (7.2).000352 (12.4)93 (11.2)History of other cancer84 (19.2)1,377 (18.8).858373 (17.4)147 (17.6).9215Index length of stay, M (SD)6.5 (9.8)5.9 (6.8).12086.6 (9.9)6.9 (10).291072.9 (9.5)72.3 (9.4).010273 (9.5)73.2 (8.5).3006Index LACE score, M (SD)Note. CHF congestive heart failure; COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI myocardial infarction.*Denotes use of Fisher's exact test.hemiplegia, severe renal disease, and rheumatologicdisease (see Table 1). After the propensity match,there were no significant differences in demographicfactors or comorbid medical conditions (see Table 1and Figure 1). Within the matched cohort, cases were73.5 years (SD: 16.3) of age on average, with 51.8%Vol. 27/No. 2Professional Case Management 61Copyright 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

TABLE 2Unadjusted Outcomes in Patients With RNCLEngagement and Referent GroupCase (%)Referent (%)p ValueAny program enrollmentOutcome67.115.3 .0001Mayo Clinic Care Transitionsenrollment60.913.9 .0001Adult Care Coordinationenrollment15.31.6 .0001Palliative care homebound2.10.1.0001Integrated communityspecialist visit10.53.4 .0001Hospitalization17.214.9.2911Emergency department visit21.019.3.4836Emergency department visit(no hospitalization)7.49.6.195266.854.6 .0001Office visitsFIGURE 1Propensity matching.being female. Most patients in the matched cohortwere White at 89.7%. For the illness burden, 41.5%had congestive heart failure and 28.2% had diabeteswith organ damage. The mean LACE score was 73(SD: 9.5).For our primary outcome of any program enrollment following hospitalization, the authors foundthat 67.1% of patients enrolled in any of the caremanagement programs of interest following RNCLengagement versus 15.3% in a group without RNCLinteraction (p .0001). For individual programenrollment outcomes, patients who interacted withRNCL had 60.9% enrollment in the MCCT program compared with 13.9% in the patients without engagement (p .0001). The authors foundsimilar significantly higher enrollment for the otherprograms of ACC, palliative care homebound program, and ICS referrals (see Table 2).Conditional logistic regression models controllingfor patient education and prior health care utilization similarly showed significant associations betweenRNCL engagement and future enrollment in caremanagement programs. Those who engaged with theRNCL were 13.7 times more likely (odds ratio [OR]:13.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 9.2, 20.2, p .0001) to have subsequent enrollment in a care management program of any kind compared with thosewho did not engage with the RNCL. Similarly, the ORof care transitions program enrollment in the intervention group compared with the control group was 11.8(95% CI: 8.1, 17.3, p .0001). The RNCL intervention group also had significantly higher odds of ACCenrollment and ICS care visits. In examining secondaryoutcomes of interest, the authors found that the RNCLintervention group was more likely to have office visits in the 30 days following their index hospitalizationcompared with those in the control group (OR: 1.6,95% CI: 1.3, 2.1, p .0001). There were no differences between the two groups when evaluating 30-dayhospital readmissions or ED visits (see Table 3).For our primary outcome of any program enrollment following hospitalization,the authors found that 67.1% of patients enrolled in any of the care managementprograms of interest following RNCL engagement versus 15.3% in a group withoutRNCL interaction. For individual program enrollment outcomes, patients whointeracted with RNCL had 60.9% enrollment in the MCCT program compared with13.9% in the patients without engagement. We found similar significantly higherenrollment for the other programs of ACC, palliative care homebound program andICS referrals.62Professional Case ManagementVol. 27/No. 2Copyright 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Those who engaged with the RNCLwere 13.7 times more likely to havesubsequent enrollment in a caremanagement program of any kindcompared with those who did notengage with the RNCL.stRenGths And liMitAtionsOur study had strengths and some limitations. In thisnovel study, an RNCL engaged 539 patients over a9-months period, 419 of which were included in thestudy. This is an encouraging level of interaction fora new program and a new role. The study had over7300 patients from whom to match, which reflectsa large volume of hospital patients who could benefit from this RNCL role. There is a substantiallylarge effect size, which also reinforces the value ofestablishing this role in the hospital and primary carepractices.Recognizing these strengths, there were alsolimitations. For our primary outcome of care management enrollment, it is possible that patients wereenrolled in care management outside of our primarycare network. This possibility is unlikely given theinfrastructure required and it would not likely favorone group over another. The authors attemptedto mitigate this limitation by limiting our study tothose patients empaneled to a Mayo Clinic primarycare provider. A second concern is the possibilityof residual bias due to unmeasured confounding.The study matched and adjusted for known predictors for illness severity. These included age, sex,comorbid health conditions, and previous utilization; however, there are potentially other predictors which are not accounted for. By implementingpropensity score matching with a limit on distanceallowed between matches, the authors were able todemonstrate adequate balance in measured covariates between the two groups and are confident thatresidual bias is limited. The authors can generalizethe population to the upper Midwest of the UnitedIn examining secondary outcomesof interest, the authors found thatthe RNCL intervention group wasmore likely to have office visits inthe 30 days following their indexhospitalization compared with those inthe control group.TABLE 3Adjusted Conditional Logistic RegressionResultsOdds Ratio for GroupEffect (Control Groupas Referent) [95% CI]p ValueAny program enrollment13.7 [9.3, 20.2] .0001Mayo Clinic Care Transitionsprogram enrollment11.8 [8.1, 17.3] .0001Adult Care Coordinationenrollment13.1 [6.2, 27.9] .0001OutcomePalliative care homebound13.7 [0.7, 290.2].0922Integrated community specialistvisit3.3 [1.9, 5.6] .0001Hospitalization1.2 [0.9, 1.7].2687Emergency department visit1.2 [0.8, 1.6].3783Emergency department visits(that did not results inhospitalization)0.7 [0.4, 1.2].2498Office visits1.6 [1.3, 2.1] .0001Note. Multivariate models were adjusted with the following covariates: numberof prior hospitalizations in the previous 12 months, number of emergencydepartment visit in the previous 12 months, and education. CI confidenceinterval.States; however, the findings cannot be generalizedbeyond this population with certainty (St. Sauveret al., 2012).iMPliCAtions FoR CAse MAnAGeMent PRACtiCeThese findings validate the importance of the RNCLrole within the hospital. Similar to findings byKaram et al. (2021) that “efforts must be directedtowards enabling the primary healthcare level ofeffectively play its substantial role in care coordination,” our study facilitates multidisciplinary teamwork to delivery care (Karam et al., 2021, p. 16).The RNCL role could help enhance enrollment incare management programs. The authors learnedthat this role helps to facilitate communicationbetween the hospital and the ambulatory clinic. Thestudy may require further validation in other settings and other groups. However, we believe thesefindings may facilitate further models to improveenrollment in care management programs followinghospital stay.ConClusionIn this study of 419 propensity matched patients,the authors found a significant association betweenengagement in RNCL and enrollment in care management programs after controlling for prior healthcare utilization and patient education. The authorsfound that over two-thirds of patients who interacted with the RNCL enrolled in some type of careVol. 27/No. 2Professional Case Management 63Copyright 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

The authors found that over two-thirdsof patients who interacted with theRNCL enrolled in some type of caremanagement program compared toonly one in nine in usual care.management program compared with only one innine in usual care. In examining individual programenrollment, the authors further found substantiallyhigher odds of enrollment across all programs forthose who engaged with the RNCL compared withthose who did not. The primary objective of this newclinical program was to increase enrollment in caremanagement programs (Flynn et al., 2021). Showingthis improvement was encouraging.Although this role has some similarities whencomparing to hospital and primary care social workroles, the RNCL is a unique individual who has arole in both the hospital and ambulatory practice.The hospital providers who help facilitate enrollmentin ambulatory programs involve social workers anddischarge planners, and their roles were previouslydescribed in this article. The communication betweenboth settings is often through a discharge summary(Mitchell et al., 2017). The RNCL serves in both hospital and ambulatory settings with a single primaryrole, which may have helped facilitate these findings.The multifaceted nature of this position allows formore efficient coordination of care management services post-discharge, which likely contributed to thesubstantial effects that were seen among the intervention group compared with usual care.The authors did not find significant differencesin hospitalizations or ED visits in the 30 days following discharge between patients interacting withthe RNCL compared with usual care. Additionalresearch could be conducted to further this study tounderstand the impact on 30-day readmissions and/orED admissions. The RNCL role does provide directcare to patients and serves as a facilitator between theambulatory care management and the patient duringthe hospital stay. However, as demonstrated by ourstudy, not all patients enroll in care management postdischarge and, thus, may not benefit from reductionsin risk of readmissions. The authors found that manysubjects enrolled in the MCCT program, which hasbeen shown to reduce hospitalization; however, notall care transitions programs have shown reduction inhospitalization (Leppin et al., 2014). Other programshave a different focus, such as referrals to specialistsin the ICS practice (Elrashidi et al., 2018). These programs do not have a specific focus on reducing hospital readmissions. This variation in enrollment and64Professional Case Managementprogram focus may explain why our findings for oursecondary outcomes were not significantly differentacross groups.REFERENCESColeman, E. A., Parry, C., Chalmers, S., & Min, S. J.(2006). The care transitions intervention: Results of arandomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(17), 1822–1828. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822Crane, S. J., Tung, E. E., Hanson, G. J., Cha, S., Chaudhry,R., & Takahashi, P. Y. (2010). Use of an electronicadministrative database to identify older communitydwelling adults at high-risk for hospitalization oremergency department visits: The elders risk assessment index. BMC Health Services Research, 10, idi, M. Y., Mohammed, K., Bora, P. R., Haydour, Q.,Farah, W., DeJesus, R., Hassan Murad, M., & Ebbert,J. O. (2018). Co-located specialty care within primarycare practice settings: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Healthcare (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 6(1),52–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.09.001Flynn, M., Swanson, K., Kronebusch, B., Sikkin, L., Niccum,K., Crane, S., Aoun, B., & Takahashi, P. (2021).Improving transitions of care for community patients:The registered nurse clinical liaison. Nursing Economics Journal, 39(3), 125–131.Grant, D. M., & Toh, J. S. (2017). Medical social workpositions: BSW or MSW? Social Work in Health Care,56(4), 215–226. nd, D. E., Vanderboom, C. E., & Harder, T. M.(2019). Fostering cross-sector partnership: Lessonslearned from a community care team. Professional CaseManagement, 24(2), 66–75. ran, P., Liew, D., Neil, C., Driscoll, A., Marwick,T. H., & Hare, D. L. (2018). Moving from heart failure guidelines to clinical practice: Gaps contributing toreadmissions in patients with multiple comorbiditiesand older age. Clinical Medicine Insights Cardiology,12, 1179546818809358.Karam, M., Chouinard, M. C., Poitras, M. E., Couturier,Y., Vedel, I., Grgurevic, N., & Hudon, C. (2021).Nursing care coordination for patients with complex needs in primary healthcare: A scoping review.International Journal of Integrated Care, 21(1), 1–21.https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5518Kelly, K. J., Doucet, S., & Luke, A. (2019). Exploring theroles, functions, and background of patient navigatorsand case managers: A sc

Toh, 2017). Mayo Clinic hospital case managers help with discharge planning as well and review medical necessity of interventions and hospital stay, based on insurance guidelines (Kelly et al., 2019). Mayo Clinic Rochester created a new role for a register nurse care liaison (RNCL). This registered nurse works to