Transcription

HANS E. JAHNKELIVESTOCK PRODUCTION SYSTEMSAND LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENTIN TROPICAL AFRICAKIELER WISSENSCHAFSVERLAG VAUK

HANS E. JAHNKELIVESTOCK PRODUCTION SYSTEMSAND LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENTIN TROPICAL AFRICAKIELER WISSENSCHAFTSVERLAG VAUK1982

Hans E. JahnkeLivestock Production Systems -id-LivestockDevelopment in Tropical Africa 1982 Kieler Wissenschaftsverlag VaukPostfach 4403, D - 2300 Kiel 1ISBN 3-922553-12-5

IN MEMORIAMHANS RUTHENBERG(1928 - 1980)

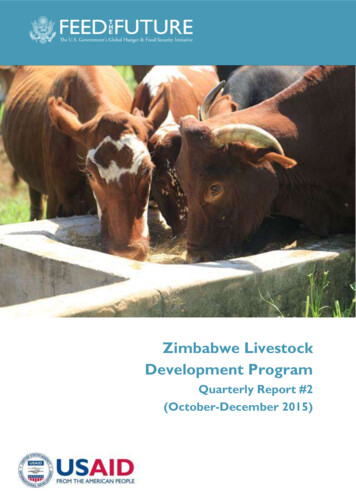

VFOREWORDbyDr.P.BrumbyDirector General, ILCALivestock are vital to subsistence and economic development insub-Saharan Africa. They provide a flow of essential food productsthroughout the year, are a major source of government revenueand export earnings, sustain the employment and income of mil lions of people in rural areas, contribute draught energy and ma nure for crop production and are the only food and cash securityavailable to many Africans. The sale of livestock and their pro ducts often constitutes the only source of cash income in ruralareas, and hence the only way in which subsistence farmers canbuy consumer goods and procure the improved seeds, fertilizers andpesticides needed to increase crop yields. Where livestock develop ment has been successfully pursued, a steady increase in the pro ductivity of food grain production and in the growth of service andconsumer industries is clearly observable.Many of the traditional livestock production systems of sub-Saha ran Africa are now in decline. Their future survival depends onenhancing their capacity to satisfy the subsistence and incomeneeds of their producers. It also depends on their impact on theland resources they use. The grasslands and browse in the pastoralareas of Africa are characterised by low levels of productivity andhigh variability in yields, both within and across years. As humanand therefore livestock populations increase, pressure on these un predictable resources grows, and with it the threat of en'ironmen tal degradation leading to further decline. There is thus an urgentneed to find ways to accelerate livestock productivity and output,so that it not only keeps pace with rising populatio i but alsocreates surpluses for market disposal. Opportunities for substantialprogress exist: in the improvement of grazing lands, health control,animal management practices, and marketing and institutional in frastructure.Research and development studies in more than a dozen institutesin tropical Africa now span several decades. These efforts haveresulted in substantial productivity gains in a number of specificsituations. However, most of these have been achieved under man Previous Pknk

VIagement conditions which are beyond the means of the majority oflivestock producers. Development efforts have often stressed tech nical innovations without an understanding of the spectrum of con sequences that can flow from such interventions in pastoral socie ties, and the outcome of past investment in livestock developmentprojects has been generally disappointing. The primary cause offailure in most cases has been the lack of adequate understandingof relationships between the biological, economic and social com ponents of each production system.Based on this premise, the research efforts of the InternationalLivestock Centre for Africa (ILCA) have focussed on the need fora thorough understanding of these relationships before committingscientists and physical resources to detailed field and componentresearch within a given system. Our baseline studies, carried outin areas representative of the wid, range of ecological and socio economic environments of sub-Saharan Africa, support the hypoth esis that research on livestock development must consider produc tion systems in their entirety. They provide the rationale forILCA's systems-oriented research strategy. Hans Jahnke, a staffmember of ILCA from its inception in 1975, has been a key figurein the formulation of this strategy, and is in a unique position toprovide a synthesis of the information accumulated by ILCA andother research and development institutes, adding his own carefuland pragmatic approach to the interpretation of the usually scantyquantitative data available.The main aim of this book is to improve the planning base forlivestock development in Africa. The author's first task has beento provide a quantitative assessment of livestock and land re sources, which forms the basis for dividing the continent intoecological zones. Livestock production in each zone is assessed bythe products provided, the functions performed and the contribu tion of livestock to the national economy. This analysis leads to aclassification of the predominant production systems in the region,ranging from extensive pastoral systems to intensive landless sys tems. The Jlassification is justified by its usefulness in identifyinglivestock development possibilities. The viewpoint expressed here isthat of an economist: change and improvement in different pro duction systems depend on relative factor endowments, technologyand pricing structure, as well as on the changing nature of pro ducer objectives and managerial skills. A central theme of thebook is that livestock development cannot be viewed as a parallelexpansion in all existing systems; priorities must be set and devel

VIuopment choices made on the basis of the relative importance andpotential of each system.Like other processes of change, livestock development is dynamicand open-ended. Systems at different stages on the developmentpath face widely differing constraints on their further improve ment. Dr. Jahnke's book is particularly valuable in this context, asit formulates specific development hypotheses amenable to empiri cal testing in specific production environments. The research taskimplied by this analysis is therefore one of ILCA's major objec tives. It is our hope that this book, which synthesizes much of thematerial in other ILCA publications, will prove a valuable sourceof information for improving food production and economic devel opment in sub-Saharan Africa.Addis Abeba, EthiopiaJanuary 20, 1982

IXAcknowledgementsThis book has arisen from my work at the International LivestockCentre for Africa (ILCA) between 1975 and 1981. Without impli cating anybody in errors and omissions and without claiming topresent a synthesis or consensus of views held there, the book is aproduct of the work of that organisation, drawing on resourcesprovided by the Consultative Group on International AgriculturalResearch.The complete list of direct and indirect contributors at ILCAsimply is too long for inclusion here and I can only ask the staffof ILCA as a whole to accept my sincere thanks for their generalsupport and for their valuable inputs. The book was started andbrought to conclusion under the directorship of Mr. David Prattand it is to him that I owe my major debt for intellectual andadministrative support and for continued moral encouragement toaccomplish the work.The members of ILCA's Programme Committee under the chair manship successively of Prof. D.E. Tribe and Dr. A. Provost haveprovided valuable suggestions and criticisms on earlier drafts. Fortheir particular efforts I must mention Prof. W. Schaefer-Kehnert,Prof. C.R.W. Spedding and Prof. H. Ruthenberg.Valuable background material was provided by FAO; Mr. G.Higgins helped with statistical data and Dr. J. Hrabovszky providedplanning figures and background calculations and he took thetrouble of commenting extensively on an earliei draft.The Institut d'Elevage et de Medecine Veterinaire des Pays Tropi caux (IEMVT) granted me access to their archives; its DirectorGene'ral Dr. A. Provost and its Assistant Director Dr. G. Tachertook the time for long discussions and provided numerous valuablesuggestions.The final draft of the work benefitted substantially from sug gestions and criticisms by my colleagues at the University of Kiel,in particular by Prof. C.-H. Hanf, Prof. W. Scheper, Dr. R. MillerDr. R. Herrmann and Dr. P.M. Schmitz and by Prof. G. Weinschenkof the University of Hohenheim.Finally I am grateful for competent technical support at first atILCA and then at the University of Kiel, where Ms. S. Lildtke, Mr.Previou.1s Page BlIY.

xF. Platte and Mr. H.-P. Schadek compiled statistics, Ms. H.J irgensen and Mr. F. Killsen prepared the drawings, Ms. S. Lemketyped earlier drafts and the tables, Ms. E. Fey and Ms. M. Krauseprepared the final typescript and Ms. H. Kross undertook thetedious editorial work.Hans E. JahnkeMarch 31, 1982Kiel, Federal Republic of Germany

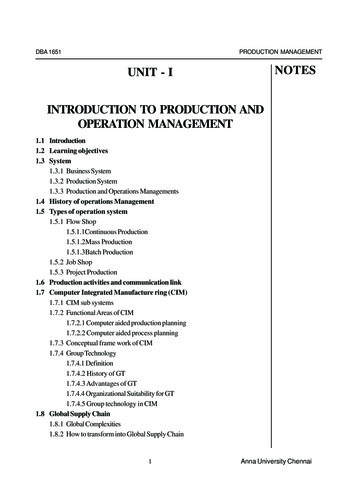

XICONTENTSList of TablesList of FiguresAcronyms of OrganizationsUnits and AbbreviationsXiVXVIIIXIXXXINTRODUCTION1.1 Background1.2 Aim and Scope1.3 Approach11362RESOURCES FOR LIVESTOCK PReDUCTION2. 1 Livestock2.2 Land2. 3 Resources by Ecological Zone9915203LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION AND PRODUCTIVITY3.1 Sector Contribution3.2 Livestock Products3.2.1 Foods3. 2.2 Materials3.2.3 Manure2424272729313.2.4 Work,323.2.5 Animals - Reproduction and Growth3. 3 Production and Productivity by Ecological Zone35364LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT AND PRODUCTION SYSTEMS4.1 Livestock Development4.1.1 Performance to-date4.1.2 The Case for Livestock Development4. 1. 2. 1 Arguments for Livestock Development4. 1. 2. 2 Demand for Livestock Foods4. 1. 2. 3 Demand for Other Livestock Products4.1.3 Development Considerations and Farm Systems4.2 The Systematics of African Livestock Production4. 2. 1 Farming Systems and Ecological Zones4. 2. 2 Livestock Type and Product4.2.3 Livestock Functions4.2.4 Livestock Management4. 3 Livestock Production Systems and their Development42424246464750515252545459635PASTORAL RANGE-LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION SYSTEMS5.1 General Characteristics5. 1. 1 Definition and Delimitation5. 1. 2 Types and Geographical Distribution5. 1. 3 Livestock Functions5.1.4 Management Aspects666666666874

XII6785.2 Production and Productivity5. 2. 1 Range Production and Carrying Capacity5. 2. 2 Livestock Productivity5. 2. 3 Land Productivity5. 2. 4 Labour Productivity and Employment Capacity5. 2. 5 Human Supporting Capacity5.3 Development Possibilities5. 3. 1 Marketing and Stratification5. 3. 2 Livestock Improvement and Disease Control5. 3. 3 Land and Water Development5. 3. 4 Institutional Development and Ranching5. 3. 5 Human Development7979818385878989939599102CROP-LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION SYSTEMS INTHE LOWLANDS6.1 General Characteristics6. 1. 1 Definition and Delimitation6. 1. 2 Types and Geographical Distribution6. 1. 3 Characteristics of Livestock Production6.2 Production and Productivity6.2.1 Fodder Productivity6. 2. 2 Livestock Productivity6. 2. 3 Productivity and Tsetse Challenge6.3 Development Possibilities6. 3. 1 Mixed Farming6. 3. 2 Strengthening the Role of Livestock6. 3. 3 Tsetse Control6. 3. 4 Other Development P-LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION SYSTEMS INTHE HIGHLANDS7.1 General Characteristics7. 1. 1 Definition and Delimitation7. 1. 2 Types and Geographical Distribution7. 1. 3 Livestock Characteristics7.2 Production and Productivity7.3 Development Possibilities7. 3. 1 Dairying - the Example of Kenya7. 3. 2 Livestock in the Development of Subsistence Farms7.3.3 Sheep Development7. 3. 4 Other Development Paths152152152153155159164164172177181RANCHING8.1 General Characteristics8. 1. 1 Definition and Delimitation8. 1. 2 Types and Geographical Distribution8. 1. 3 Production Characteristics182182182182184

Xm9Ifn8.2 Production and Productivity8. 2. 1 Fodder Productivity8. 2. 2 Livestock Productivity8. 2. 3 Physical Performance and Financial Viability8.3 Development Possibilities8. 3. 1 Basic Opportunities and Constraints8. 3. 2 Ranching Development in Arid Areas8. 3. 3 Ranching Development in Humid Areas187187188190194194196198LANDLESS LIVESIOCK PRODUCTION SYSTEMS9.1 Definition and Delimitation9. 2 Pig Production Systems9. 3 Poultry Production Systems9.4 Intensive Beef Production Systems9. 5 Development Possibilities202202202206210214CONCLUSIONS FOR LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENTPLANNING10. 1 The Importance of Planning for Livestock Development10. 2 Production Systems and Strategy Issues in LivestockDevelopment Planning10. 3 The Role of Monitoring for Livestock DevelopmentPlanning and for this Study21821822122611ANNEX22912BIBLIOGRAPHY241

XIVLIST OF TEXT TABLES2.12.22.32.42.52.62. Livestock Population in Tropical Africa by Species inNumbers and in Tropical Livestock Units (TLU) 1979Distribution of the Ruminant Livestock Population bySpecies and Regions/Countries in Tropical Africa 1979Distribution of the Equine Livestock Population bySpecies and Regions/Countries in Tropical Africa 1979Distribution of Pigs and Poultry and of the HumanPopulation by Region in Tropical Africa 1979Extent of Ecological Zones by Region in Tropical AfricaExtent of Tsetse Infestation by Ecological Zone inTropical AfricaRuminant Livestock Population by Species and EcologicalZone in Tropical Africa 1979Livestock, Land and Labour Resources by EcologicalZone in Tropical Africa 1979Estimated Per-caput Income, Agricultural GDP and Livestock GDP in Tropical Africa by Country Groups 1980Selected Methods of Valuation of Livestock Food ProductsFood Production of Livestock in Tropical Africa 1978Quantity and Valueo of Hides, Skins and Wool Productionin Tropical Africa 1979Population of Work Animals by Regions in TropicalAfrica 1979Growth of Livestock Herds and Flocks in TropicalAfrica 1969-71 to 1979Estimate of the Value of the Standing Stock of MeatAnimals in Tropical Africa 1979Productivity Indicators of Livestock by Species inTropical Africa 1975/80Availability of Meat and Milk from Ruminants by Ecological Zone in Tropical Africa 1975/80Productivity Indicators of Livestock Production inTropical Africa 1975/80Indicators of Expansion and Productivity Growth in Cropand Livestock Production in Tropical Africa 1963-75Livestock Production and Productivity in Africa 1950,1970 and 1975/80Regional Average Income Elasticities of Demand forSelected Crop and Livestock Foods in Tropical Africa1975-2000Projection of Domestic Demand for Selected Crop andLivestock Foods in Tropical Africa 1975-2000Indicators of Input Requirements of AgriculturalDevelopment in Tropical Africa 84951

XV5.15.25.35.45.55. 65. 76. 16.26. 36.46.56.66. 76.86. 96. 106.117.17.2Types and Characteristics of Pastoral Production'Systems in Tropical Africa in Dependence of the Degreeof AridityHousehold Budget and Diet Composition of DifferentPastoral Households in West Africa (Chad, Niger andMali)Utilizable Primiry Production and Carrying Capacityin Dry Rangelands in Tropical AfricaProductivity of Camels, Cattle, Sheep and Goats inPastoral Systems in Tropical AfricaIndicators of Land Productivity in Pastoral Systems inTropical AfricaIndicators o.".ivestock Production and Labour Intensityand Labour Productivity in the Dry Areas of Australia(1968-1969 tu 1970-1971)Estimate of Human Supporting Capacity (IISC) of LowRainfall Areas in West and East AfricaSuggested Maximum Sustainable R-Values by Soil andEcological ZoneFeed Availability and Carrying Capacity in the MoreHumid Lowland Areas of Tropical AfricaYields and Nutritive Value of Upland Savanna inKatsina and Zaria Survey Areas 1967-69Straw Yield ant Nitrogen Content of Crop Residuesin the Semi-arid ZoneMeat and Milk Productivity of Cattle in SelectedCountries of the Lowland Crop-livestock Zone ofTropical Africa 1979The Importance of Animal Draught, Tractors and HandLabour in Meeting the Labour Requirements of CropAgriculture in Lowland Tropical Africa 1975Productivity of Trypanotolerant and Zebu Cattle inThree Locations at Different Levels ,f TsetseChallenge and ManagementProductivity of Trypanotolerant Cattle Groups UnderDifferent Management Systems and Levels of TsetseChallengeProductivity Traits of Trypanotolerant and Non-tolerantGroups of Sheep and GoatsAdoption of Agronomic Improvements (Other than AnimalDraught) and Yield Development in Cotton Growing inMali 1961/62 to 1964/65Areas Freed from Tsetse Flies in Nigeria, Zimhabwn,Tanzania and UgandaExtent of Highland Areas in Tropical Afric- oy RegionsAgroclimatic Variation within the Highland 3153154

. 39.49.59.69.79.8Livestock Contribution to Farm Income in SelectedFarming Systems in the Kenyan HighlandsMilk Production and Productivity by ManagementSystems and Cattle Breed in Kenya 1974Dry Matter (DM) Production in the Process of LandUse IntensificationPrices and Price Indices for Grade Dairy Heifers,Maize, and Milk 1940-1977Changes in Farm Management Data in the Course ofIntensificationIncome from Dairying and Total Income in the Courseof IntensificationGross Value of Production and its Composition for aTypical Subsistence Farm in Ada DistrictAnalysis of Subsistence and Feed Production Capacityof Typical Ada District Farm Following Traditionaland New Cropping PatternProductivity Indicators of Indigenous Cattle in TropicalAfricaLiveweight Gains of Adult Zebu Steers under Commercial Conditions (Mokwa Ranch, Nigeria)Possible Growth Rate of Cattle Breeding Herd as aFunction of Weaning Rate and Heifer MortalityPossible Offtake Rate of Self-contained Cattle Herdas a Function of Maturity Age and Weaning RatePlanned and Achieved Calving Rates on Newlyestablished Ranches in Tropical AfricaComparison of the Performance of African IndigenousPigs with Swedish Landrace in Southern AfricaTypes of Commercial Pig Production Systems andMajor Production CharacteristicsEstimate of Pig Production and Productivity of Traditional and Commercial Systems in Tropical Africa 1979Increase of the Pig Population and of Pork Production1969-71 to 1979Increase of the Chicken Population and of PoultryProduction 1969-71 to 1979Total Beef Fattening Costs in Dependence of Conversion Ratio and Daily Liveweight GainTypical Grain/Beef Price Ratios in World RegionsPotential Availability and Feed Value of Main Agroindustrial By-products Suitable for Animal Nutritionin Tropical Africa 05206209212213216

XVIILIST OF ANNEX TABLES1234567891011The Ruminant Livestock Population in Tropical Africaby Country 1979The Equine, Pig and Chicken Population in TropicalAfrica by Country 1979Gene al Agricultural Indicators of Tropical Africa byCountry 1979Extent of Ecological Zones in Tropical Africa byCountry 1979Extent of Tsetse Infestation in Tropical Africa by Eco logical Zone by CountryDistribution of Human Agricultural Population inTropical Africa by Ecological Zone by Country 1979Distribution of Cattle in Tropical Africa by EcologicalZone by Country 1979Distribution of Sheep in Tropical Africa by EcologicalZone by Country 1979Distribution of Goats in Tropical Africa by EcologicalZone by Country 1979Distribution of Ruminant Livestock Units in TropicalAfrica by Ecological Zone by Country 1979GDP, GDP Per Caput and Sector Contributions byAgriculture and Livestock in Tropical Africa byCountry 1980

XVIIILIST OF .57.18.19.1Species Composition of the Livestock Population inTropical Africa 1979Regions of Tropical AfricaThe Ecological Classification Scheme Used and Approximate Correspondence with Other Classification SchemesThe Ecological Zones of Tropical Africa and the Extentof Tsetse InfestationProportion of Agriculture in GDP and Proportion ofLivestock in Agricultural GDP in Tropical AfricanCountries 1980Total Costs of Aid-assisted Livestock DevelopmentProjects in Tropical Africa 1961-1975Diagrammatic Representation of Crop Production andLivestock ProductionPastoral Peoples of Tropical AfricaHypothetical Scheme of Food Productivity of the Landin Cropping and Pastoral Land UseEffect of Yield-increasing Practices on Range Productionin the SahelSuitability Classification and Yields of Major Food Cropsin the African Tropical Lowlands by Ecological Zoneat Low Input LevelDiagrammatic Representation of Farming Systems byEcological Conditions and Population Pressure in theLowlands of Tropical AfricaTsetse and Cattle Distribution in East AfricaDelimitation of the Semi-arid Zone in West Africain Relation to Tsetse Fly Distribution and ZebuCattle PredominanceDistribution of Cattle on the Village Land During theDifferent Seasons in Golonpoui, Northern CameroonGrade Dairy Cattle Development on Large and SmallFarms in Kenya 1935-1975Stages in Ranch Development and Water DevelopmentEffects of Intensive Feeding on the Growth Pattern 11

XIXACRONYMS OF SATECSEDESUNCTADUNDPUNECAUNFPAUSAIDUSDABureau pour le Ddveloppement de la Production Agricole,ParisCentre d'Etudes et d'Expdrimentation du MachinismeAgricole TropicalCompagnie Frangaise pour le D veloppement des FibresTextiles, ParisCentre for Research on Economic Development, Universityof MichiganCentre de Recherches Zoatechniques, Bouak4Economic Development Institute of the World Bank,Washington, D. C.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations,RomeGroupement d'Etudes et de Recherches pour le De'veloppe ment de l'Agronomie Tropicale, ParisGesellschaft ffir Technische Zusammenarbeit, EschbornInterafrican Bureau for Animal Resources, NairobiInternational Bank for Reconstruction and Development,Washington, D. C.Institut d'Elevage et de Mddecine Vdtdrinaire des PaysTropicaux, Maisons-Alfort, ParisInternational Fertilizer Development Centre, AlabamaInstitut filr Wirtschaftsforschung, MfinchenInternational Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, D. C.International Livestock Centre for Africa, Addts AbebaKenya Cooperative Creameries, NairobiLivestock and Meat Board, Addis AbebaNational Animal Production Research Institute, KadunaOrganization of African Unity/ Scientific and TechnicalResearch CommissionOrganisation Mondiale pour la SantdSoci td d'Aide Technique et de Coopdration, ParisSocidtd d'Etudes pour le Ddveloppement Economique etSocial, ParisUnited Nations Commission for Trade and Development,GenevaUnited Nations Development Programme, New YorkUnited Nations Economic Commission for Africa, AddisAbebaUnited Nations Fund for Population ActivitiesUnited States Agency for International DevelopmentUnited States Department of Agriculture

UNITS AND ABBREVIATIONSAT 2000CDWCPDCPDMFUGDGDPGEGPHSCLWMDEMEMHMTn. ap.n. av. TCUTLUUBTAgriculture: Towards 2000 (FAO publication)Cold dressed weightCrude proteinDigestible crude proteinDry matterFodder unit (equivalent to 0. 7 of a starch unit after Kellner)Growing daysGross don-estic productGrain equivalentGrowing periodHuman supporting capacityLiveweightMan-day equivalentMan equivalentMan-hourMetric tonne (the symbol "t" is also used)Not applicableNot availableUnited States (US) dollarsTropical cattle unit (a bovine of 175 kg LW)Tropical livestock unit (an animal (ruminant) of 250 kg LW)Unitd de b'tail tropical (an animal (ruminant) of 250 kg LW)

11.1IntroductionBackgroundTropical Africa is one of the least developed world regions com prising most of the world's poorest countries. Agriculture as themainstay of the economies hardly keeps pace with populationgrowth. Self-sufficiency ratios for cereals and other staple foodsare generally declining; the dependence on food imports is increas ing. The performance of livestock as part of agriculture is partic ularly disturbing. While some modest productivity improvementshave taken place in cropping, livestock production increases in thepast have been largely due to numeric expansion of herds andflocks rather than to improvement of the productivity. Major live stock areas like the Sahel and parts of Eastern Africa provide anextremely fragile environment in which the constant threat ofdroughts affects not only the survival of livestock but that of thehuman population as well. Overgrazing and resource degradationcharacterize livestock production over much of the region whilethe apparent potential in other regions is not used at all. The useof animal traction for cropping and the integration of livestockinto farming are uncommon. Overall the levels of livestock produc tivity and of availability of livestock products like meat, milk andeggs for the human population are the lowest of any world regionwhich is all the more serious since, in many areas, livestock pro ducts constitute the major source of subsistence. Even at the pre vailing low levels of consumption production does not keep pacewith demand and the region as a whole moves towards the positionof a net importer of livestock products despite its apparent poten tial for livestock production.For general agriculture as well as for livestock production theneed for development is great and the modest objective of main taining per caput levels of production constitutes a formidablechallenge in the light of a rapidly growing human population. Ef forts at agricultural and livestock development will need to becarefully planned and take account of the pronounced diversity ofthe natural and human environment. The agro-climatic conditionsrange from extreme aridity in deserts and desert-like areas to ex treme humidity in areas whose natural vegetation is dense rainfor ests; in addition altitude intervenes rendering highlands ecologicallydifferent from the low-lying areas. In all ecological zones thereare areas of high population density with intensive forms of landuse as well as vast stretches of land, hardly used and almost void

2of man and stock. Diversity is further accentuated by the coexist ence of pre-technical forms of agricul-tur.e and modern forms in troduced into Africa in the last 100 yea'r, sometimes only in thepast two decades. Shifting cultivation in the rain forests and pas toral nomadism in the arid zone have existed in their present formfrom times immemorial; commercial plantations, ranching, large scale farming and industrial poultry complexes are "children of theindustrial revolution" (Grigg 1974) transplanted to Africa in recenttimes. The distribution pattern of the human and the livestockpopulations and the penetration of modern forms of agriculturehave bcen influenced in a manifold and often obscure way by thepresencu of tsetse flies and the diseases they carry, a factorwhich is unique to Tropical Africa, and which affects 10 millionsquare kilometers or 40% of the land area considered here.Livestock production is a form of agricultural production withmany facets and the manifestation of these facets differs fromone situation to another. It is obvious that livestock production bya nomad who keeps camels for milk to secure his subsistence isdifferent from that of a peasant who raises some poultry in hisfarm yard for sale on the market. The different livestock species- camels, cattle, sheep, goats, equines*, pigs and poultry - varyradically in their management requirements, their production andproductivity and also in the products they supply and the functionsthey fulfill. But one and the same species may also be held forcompletely different purposes: On some farms cattle are kept toproduce beef for sale, on others to supply clung for the fields andto provide tractive force in farm work. In addition the same pro duct and function, say meat for sale, can be provided by radicallydifferent management principles; long-range migration as a formof adaptation to ecology in ii pre-technical world in one case, andthe application of modern technology in an artificially controlledenvironment in another. And the functions of livestock are by nomeans restricted to production. The keeping of livestock for pres tige and the payment of bride price in the form of cattle areonly examples of the role of livestock that pervades the emotional,social and cultural spheres of many African societies.Livestock production in Tropical Africa is characterized by greatcomplexity not only in environment but also in livestock types,products, functions and management principles and is compoundedby often perplexing interactions with the human sphere. This com * As a group of species to include asses, mules and horses.

plexity constitutes a formidable challenge for the design of devel opment efforts, further complicated by the generalized and oftendiscouraging lack of data. In this light it is not surprising that ef forts at livestock development are beset with problems and havedone little to improve overall performance levels. Moreover, andalso as a consequence, the reasons for success or failure of suchdevelopment efforts are little understood.The complexity of livestock proddoction and develcjpment in TropicalAfrica is certain to have been rationalized arid broken clown inmany an experienced mind,anfl accessible trea exist.a. systemaicnot buttise of the subject doeso1.20Aim and ScopeThis study aims to 4mprovd She pfahni-nm J',zfo'r. vestQo,. ,opment in Tropical Africa by' ringin :ordej j'o t eflivestock production phenomeja thr9illt th* . ,bcept f,.pro;i(.if.%nsystems, by assessing the development .L')bd0Sss bitltt"th.cb :.didf.-.ferent production systems and by*"Drtvldin" ui*nttat., ;.,hirju atio *, .on the resource base anti productio-t"a:[us, -'".To order the phenomena a concept ooaf .Jivest ck .pldYMTA .t.ott.orms,,,is developed with the specific,, puipo.se.of. b'eng.[iYj' r"th exsessment of development opportunitiis and dorjst r a'it4 yli,'roften than not, are interwoven with the hum'a6 enytb.frlennt:.'is, ing agricultural typologies, even if'they 'iaeredtnijly.a ibl4prove deficient in that respect. The aitefnati'v of p .Vii :'atmgroupings from a theory of their differentiation' (e.g.-. itl distarfce *from the market or the factor proportions av'allal) rtypology that reflects too narrow a spectrum of rea,]it .OiieOn iSleft without an entirely satisfactory solution t

Jan 20, 1982 · 5.3 Development Possibilities 89 5. 3. 1 Marketing and Stratification 89 5. 3. 2 Livestock Improvement and Disease Control 93 5. 3. 3 Land and Water Development 95 5. 3. 4 Institutional Development and Ranching 99 5. 3. 5 Human Development 102 6 CROP-LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION