Transcription

United StatesDepartment chReportNumber 140August 2012Characteristics and InfluentialFactors of Food DesertsPaula DutkoMichele Ver PloegTracey Farrigan

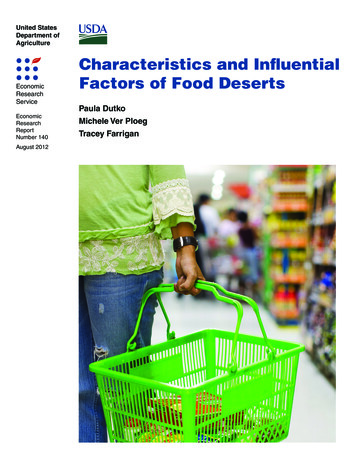

www.sda.govu.serVisit Our Website To Learn More!Find additional information on food -desert-locator.aspxRecommended citation format for this publication:Dutko, Paula, Michele Ver Ploeg, and Tracey Farrigan. Characteristics andInfluential Factors of Food Deserts, ERR-140, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, August 2012.Use of commercial and trade names does not imply approval orconstitute endorsement by USDA.Cover photo credit: Shutterstock.The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all itsprograms and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age,disability, and, where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parentalstatus, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal,or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any publicassistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Personswith disabilities who require alternative means for communication of programinformation (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’sTARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination write to USDA, Director, Office of CivilRights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 orcall (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equalopportunity provider and employer.

A Report from the Economic Research ServiceUnited StatesDepartmentof AgricultureEconomicResearchReportNumber 140August 2012www.ers.usda.govCharacteristics and InfluentialFactors of Food DesertsPaula DutkoMichele Ver PloegTracey FarriganAbstractUSDA’s Economic Research Service previously identified more than 6,500 food deserttracts in the United States based on 2000 Census and 2006 data on locations of supermarkets, supercenters, and large grocery stores. In this report, we examine the socioeconomicand demographic characteristics of these tracts to see how they differ from other censustracts and the extent to which these differences influence food desert status. Relative toall other census tracts, food desert tracts tend to have smaller populations, higher ratesof abandoned or vacant homes, and residents who have lower levels of education, lowerincomes, and higher unemployment. Census tracts with higher poverty rates are morelikely to be food deserts than otherwise similar low-income census tracts in rural and invery dense (highly populated) urban areas. For less dense urban areas, census tracts withhigher concentrations of minority populations are more likely to be food deserts, whiletracts with substantial decreases in minority populations between 1990 and 2000 wereless likely to be identified as food deserts in 2000.Keywords: food deserts, food access, low income, census tractsAcknowledgmentsThe authors are grateful to our reviewers, Susan Chen of the University of Alabama, LisaPowell of the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Alisha Coleman-Jensen of ERS. Wethank David Smallwood, Ephraim Leibtag, and Mary Bohman of ERS for comments onmultiple drafts of this report. We acknowledge participants at presentations of this paperat the 2011 Southern Economics Association Annual Conference in Washington, DC, andat the AAEA/EAAE Food Environment Symposium at Tufts University in May 2012 fortheir thoughtful suggestions. Thanks also to Priscilla Smith for editing the report and toCynthia A. Ray for providing design and layout. Any remaining errors and omissions arethe sole responsibility of the authors.

ContentsSummary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iiiIntroduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1Literature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Method for Defining and Measuring Food Deserts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Descriptive Analyses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Results: Comparing Food Desert Tracts With All Other Tracts . . . . . . 9Demographic Characteristics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Economic Characteristics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Transportation and Mobility Characteristics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Changes in Food Desert Tract Characteristics Over Time . . . . . . . . . . 15Demographic Changes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15Economic Changes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17Transportation and Mobility Changes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19Regression Analysis: Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Selection of Independent Variables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Regression Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29iiCharacteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts / ERR-140Economic Research Service/USDA

SummaryWhat Is the Issue?USDA’s Economic Research Service previously identified approximately6,500 food desert tracts in the United States based on 2000 Census and 2006data on locations of supermarkets, supercenters, and large grocery stores. Thesefood deserts are areas where people have limited access to a variety of healthyand affordable food. As policymakers consider interventions to increase foodaccess, it is important to understand the characteristics associated with theseareas, such as income, vehicle availability, and access to public transportation.In this report, we examine the socioeconomic and demographic characteristicsof these census tracts and also examine which of these characteristics distinguish food desert tracts from other low-income census tracts.What Did the Study Find? Areas with higher levels of poverty are more likely to be food deserts,but for other factors, such as vehicle availability and use of public transportation, the association with food desert status varies across very denseurban areas, less dense urban areas, and rural areas. Areas with higher poverty rates are more likely to be food deserts regardless of rural or urban designation. This result is especially true in verydense urban areas where other population characteristics such as racialcomposition and unemployment rates are not predictors of food desertstatus because they tend to be similar across tracts. In all but very dense urban areas, the higher the percentage of minoritypopulation, the more likely the area is to be a food desert. Residents in the Northeast are less likely to live far from a store than theircounterparts in other regions of the country with similar income levels. Rural areas experiencing population growth are less likely to befood deserts.How Was the Study Conducted?To provide a consistent, national-level estimate of the number of low-incomeareas in which a substantial number or share of residents is far from a supermarket or large grocery store, USDA’s Economic Research Service applieda census tract-level definition of food deserts—areas with limited access toaffordable and healthy food—to the contiguous United States using 2000Census data. The 2000 Census data and 2006 store location data that wereused for this analysis were the most recent demographic and store data available at the time this analysis was conducted.This study uses data from the 1990 and 2000 Census, as well as 5-yearaverage data from the 2005-2009 American Community Survey (ACS), todescribe changes in characteristics of the 6,529 food desert census tracts overtime, relative to changes in all other tracts. We focus particularly on population density, poverty rates, unemployment, education, race/ethnicity, income,and vehicle ownership status.iiiCharacteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts / ERR-140Economic Research Service/USDA

We first provide a statistical description of tracts classified as food desertsversus all other tracts to give a broad image of how food desert tracts differ.We then conduct regression analysis to determine which characteristics aremost strongly associated with whether a low-income census tract is alsoa food desert. We model the probability that a census tract will be a fooddesert using a multivariate logit model to assess the impact of factors suchas population and housing characteristics; racial and ethnic composition;unemployment; poverty; and changes in these characteristics from 1990 to2000. Separate analyses are performed for urban areas and rural areas inorder to accommodate different definitions of food deserts and systematicdifferences in tract characteristics between rural and urban areas. We alsofurther distinguish very dense urban areas from less dense urban areas forthe multivariate analysis.ivCharacteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts / ERR-140Economic Research Service/USDA

IntroductionIn the 2008 Food, Conservation and Energy Act (2008 Farm Act), Congressdirected the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to assess the extent ofareas in the United States where people have limited access to a variety ofhealthy and affordable food. Commonly referred to as “food deserts,” theseregions of the country often feature large proportions of households withlow incomes, inadequate access to transportation, and a limited number offood retailers providing fresh produce and healthy groceries for affordableprices. In response to this directive, USDA published Access to Affordableand Nutritious Food: Measuring and Understanding Food Deserts and TheirConsequences (USDA, 2009). The report measured the extent of limited foodaccess in the United States, highlighted potential sources and consequencesof the problem, and suggested general policy solutions. The report found,among other conclusions, that 23.5 million people live in low-income areasthat are further than 1 mile from a large grocery store or supermarket, andthat 11.5 million of these people have low incomes themselves.Building on these findings, we examine what systematic socioeconomic anddemographic differences exist between food deserts and other low-income areas.Increased attention to national health issues, such as the rising incidence ofobesity and the growing prevalence of diabetes and other weight-related diseases,especially in children, has made the concept of healthy food access increasingly important in the realm of public policy. New Orleans, New York City, andPennsylvania have implemented or are developing programs to improve accessin underserved areas. One national effort, First Lady Michelle Obama’s Let’sMove! campaign, considers access to healthy food one of five pillars in the effortto address childhood obesity. A plan, the Healthy Food Financing Initiative(HFFI), has been proposed in Congress to bring affordable, nutritious food toareas of low access and low income.A working group comprised of staff from the U.S. Departments of theTreasury, of Health and Human Services, and of Agriculture is coordinatingand sharing information about strategies to expand the availability of nutritiousfood in underserved areas. In cooperation with that working group, researchersfrom USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) developed a census tractlevel definition of food deserts in order to start identifying areas of the Nationthat may be in need of improved food access. Census tracts are identified asfood deserts if they meet both low-income and low-food-access criteria. Usingthe specific definitions of both low income and low access (as detailed in thesubsequent discussion), 6,529 census tracts were identified as food desertsacross the Continental United States and mapped through an online mappingtool.1 These tracts were identified as food deserts based on 2000 Census dataand 2006 data on locations of supermarkets, supercenters, and large grocerystores, which reflected the most recent demographic and store data available atthe time of the analysis.1Seethe Food Desert Locator: locator.aspx/.The relevance of food deserts to discussions of public health and food accesspolicy nationwide makes critical the task of isolating potential causes of lowaccess areas. As a first step toward understanding this relationship, we exploreover time the demographic characteristics of the 6,529 tracts identified as fooddeserts. Using data from the 1990 and 2000 decennial censuses, as well as1Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts / ERR-140Economic Research Service/USDA

from the 2005-2009 American Community Survey (ACS), we compare theeconomic and demographic traits of census tracts identified as food desertswith traits of all other tracts, as well as how these statistics may have changedbetween survey years. We first use descriptive statistics to provide a broadpicture of how food desert tracts differ from all other census tracts, examiningdemographic, economic and employment, population density, and commutingpatterns of census tracts. Next, we explore more specifically the characteristics associated with combined low income and low access, using multipleregression analysis to examine which of these characteristics are important inexplaining whether a low-income tract is a food desert.Our analysis has several practical motivations. First, we want to betterunderstand this national measure of food deserts and how the designationof some low-income tracts as food deserts breaks down along populationand economic characteristics. Second, by contrasting the population characteristics in areas of low access with those of other low-income areas, wecan detect any systematic differences in the composition of food deserts.Identifying economic and demographic characteristics that are closely associated with low access to supermarkets and grocery stores will help policymakers better understand those neighborhoods with food access limitations,how they have changed over time, and potential barriers other than limitedaccess to healthy food faced by residents of these areas. This is useful forproviding surveillance for areas that may be at risk of becoming food desertsand can aid policymakers in formulating policies suited to the specific needsof these communities. Finally, results from this analysis can help policymakers and public health officials develop hypotheses to study further themechanisms by which food deserts arise, thus allowing policymaking toaddress root problems rather than mere symptoms.We next review the literature on both how community food access has beenmeasured and the characteristics of areas with limited access. Then wedescribe how the census tract-based measures of food deserts were derivedand implemented. This is followed by a presentation of the methods used inthe analysis and, finally, by the results and conclusions.2Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts / ERR-140Economic Research Service/USDA

LiteratureAreas with limited access to healthy, affordable food often lack access toother services as well, such as banks, health care, transportation infrastructure, and parks or recreational areas. In addition to having poor access, residents of impoverished or deprived areas frequently face higher prices forfood and other necessities. Poor education and limited health care servicesin conjunction with high prices for fresh produce and other healthy foodmay result in poor diet and adverse health outcomes for residents of theseareas. Access to affordable and nutritious food may also be important for theeffectiveness of government benefit programs: an analysis using data from anelectronic benefits transfer (EBT) demonstration in Dayton, OH, concludedthat improved access to large grocery stores can increase the welfare ofSupplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients by an estimated value of 2.78 to 7.76 per month (Feather, 2003). SNAP is the nameof the former Food Stamp Program. These issues have motivated researchersto attempt to characterize low-access areas and to determine what demographic and economic factors influence low access.Past studies have typically considered the correlation between demographicand socioeconomic characteristics such as race, ethnicity, income, education,deprivation, and roadway connectivity, among other features of an area, withthe level of food store access. Most of these studies have been conducted inlocalized areas such as neighborhoods or cities, but recently two noteworthystudies have been conducted at a national level (Powell et al., 2006; USDA,2009). The localized and national studies varied in their measures of foodstore access, including distance to a supermarket, number of grocery stores orfast food restaurants per capita in a geographical area, vehicle ownership, andthe ratio of stores that carry healthy food options to stores that only carry lesshealthy food options.Perhaps because of the wide variety of measures used and places examined,study results have not reached a consensus on the characteristics of areasthat lack access to healthy food. Studies have produced conflicting results asto the correlation among race, income, and access to healthy and affordablefood. Many researchers have concluded that neighborhoods consistingprimarily of minorities—in particular, African Americans—with lowincomes have fewer supermarkets than wealthier, predominantly Whiteneighborhoods (Berg and Murdoch, 2008; Powell et al., 2006; Block et al.,2008; Larson et al., 2009). Others, however, have found either no correlation,or that minority and low-income neighborhoods have a greater number ofgrocery stores and are closer to these stores than wealthier areas (Alwittand Donley, 1997; Moore and Diez Roux, 2006; Opfer, 2010; and Sharkeyand Horel, 2008). These mixed results may not be surprising because thesestudies are of localized areas. However, results from the two national-levelstudies are also inconclusive. Powell et al. (2006) found that ZIP Codes withmore minorities and lower income populations had fewer chain supermarketsbut more nonchain supermarkets. USDA (2009) found that, on average,low-income and minority populations were closer to supermarkets thanhigher income individuals and non-Hispanic Whites. Multivariate analysistechniques, however, showed that measures of income inequality and racialsegregation were important predictors of low access in urban core areas; the3Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts / ERR-140Economic Research Service/USDA

most important factor in rural areas was lack of transportation infrastructure(USDA, 2009).The lack of consistent findings in this literature leads us to examine furtherthe relationship between neighborhood characteristics and food access. Ouranalysis builds upon previous studies and, in particular, components of USDA(2009) but is unique, however, in other ways. First, the census tract-baseddefinition of a food desert is based on the methods and data used in the 2009USDA report but has been adapted to fit policy needs and to be consistentwith multiple Federal agencies’ programs. Unlike previous studies, ouranalysis uses multiple years of census data to understand how changes in thepopulation are correlated with food deserts. By using data from the 1990 and2000 Census and from the 2005-2009 American Community Survey, we willbe able to assess how factors such as changes in an area’s overall populationor changes in the ethnic and racial composition of an area are correlated withfood access. This information could help predict which areas may be at risk ofbecoming food deserts and which areas may see improvements in food access.4Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts / ERR-140Economic Research Service/USDA

Method for Defining and Measuring Food DesertsThe 2009 USDA report measures the distance to the nearest healthy-foodretailer, using the locations of supermarkets and large grocery stores as aproxy, by referencing 1-square-kilometer grids for geographical analysis.These grids come from the Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center(SEDAC) and are based on information from the 2000 Census of Population(SEDAC, 2006). These population data (including socioeconomic and demographic data), which are released at the block group level, are first allocatedto blocks and then allocated aerially down to roughly 1-square-kilometergrids across the Continental United States. For each grid cell, the distancefrom its geographic center to the nearest supermarket or large grocerystore is used to measure access for people who live in that grid. Grids thatare farther than a specified distance from the nearest supermarket or largegrocery store are considered areas of low access, and low-access areas witha large percentage of low-income population are noted in particular. Use ofthe grid-level data provides two important benefits for the analysis: first, thedata provide greater accuracy in estimating where people and households arelocated than data on larger geographic areas, such as census tracts; thus, theyprovide better precision in measuring distance to stores. Second, the processof allocating census data to 1-square-kilometer grid cells transforms theirregular shapes and sizes of census geographies or other geographies, suchas ZIP Codes, into regular grid cells.While the 1-square-kilometer grid-based measures increase the precision inmeasuring where people are and how far they are from sources of healthyfood and provide consistency in defining geographic areas across the country,the SEDAC grids are not widely used geographic units. Currently, no standardized nomenclature exists to identify a specific grid (as counties, ZIPCodes, or census tracts can be identified), and they cannot easily be linkedto other geocoded data. For this reason, the area-based definition of a fooddesert uses the census tract as the geographic unit of analysis because it ismore commonly used and has a standardized numbering system.Census tracts are subdivisions of a county, containing between 1,000 and8,000 people and ideally encompassing a population of about 4,000. Inorder to establish a consistent definition for national comparison, we definefood deserts as low-income tracts in which a substantial number or proportion of the population has low access to supermarkets or large grocerystores. Low-income tracts are characterized by either a poverty rate equal toor greater than 20 percent, or a median family income that is 80 percent orless of the metropolitan area’s median family income (for tracts in metropolitan areas) or the statewide median family income (for tracts in nonmetropolitan areas). This definition of low-income tracts is used to designatetracts that are eligible for the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s NewMarkets Tax Credit (NMTC) program.2 Low access is characterized by atleast 500 people and/or 33 percent of the tract population residing more than1 mile from a supermarket or large grocery in urban areas, and more than 10miles in rural areas.32Foradditional information onthe NMTC, see: http://www.cdfifund.gov/what we do/programsid.asp?programID 5/.3The1-square-kilometer grids arestill used to calculate the number ofpeople who are more than 1 or 10 milesfrom a supermarket, which are thenaggregated to the census tract level.5Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts / ERR-140Economic Research Service/USDA

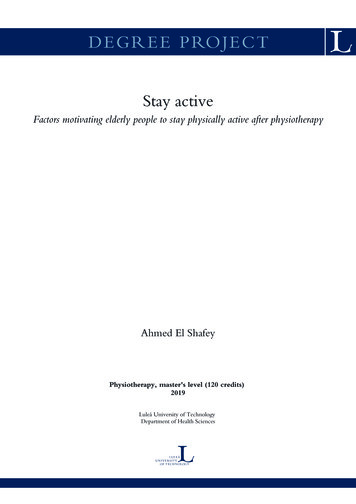

Information on supermarket and large grocery store locations comes froma directory of supermarkets and large grocery stores, defined as food storeswith at least 2 million in sales that contain all the major food departmentsfound in a traditional supermarket. The directory was developed from a listof stores authorized to receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program(SNAP) benefits and was augmented by data from Trade Dimensions’TDLinx (a Nielsen company), a proprietary source of individual supermarketstore listings. Both sets of data were provided for the year 2006.Using this definition, we identified 6,529 census tracts that met the definitionof “food desert” based on data from the 2000 Census of the Population, themost recent detailed demographic data available at the time of the analysis.Table 1 provides a breakdown of the number and percentage of all tracts thatare food deserts over all census tracts, for tracts that are designated as NMTClow-income tracts, and separately for rural and urban areas. Our descriptive analysis compares the demographic characteristics of those 6,529 tractsrelative to the characteristics of all census tracts that are not considered fooddeserts by rural and urban status. We also compare changes in these characteristics over time to explore how demographic shifts might be associatedwith food desert areas. Our multivariate analysis only considers census tractsthat are designated as low-income tracts.Table 1Number and percentage of food desert tracts by rural and urban status and by low-income statusOverallRuralUrban6,5292,2044,175Number of low-income tracts24,9276,51917,940Total number of tracts64,99913,82750,784Food desert tractsPercentFood desert tracts as percentageof low-income tracts26.233.823.3Food desert tracts as percentageof total tracts10.015.98.2Note: Totals for rural and urban sets exclude tracts with greater than 50 percent of the population living in group quarters, which eliminates 710tracts—116 rural and 594 urban.Low-income census tracts are those with: a poverty rate 20 percent; median family income 80 percent of statewide median family income(tracts outside metro areas) or median family income 80 percent of the greater of statewide median family income (tracts outside metro areas)or the median family income of the metropolitan area.Source: Authors’ calculations using Census 1990 data and Census 2000 data from National Change Database as well as U.S. Department ofCommerce, U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2005-09 data.Key TermsLow-income areaA tract in which the poverty rate is greater than or equal to 20percent; or in which median family income does not exceed 80percent of the statewide or metro-area median family incomeFood desertA census tract that meets both low-income and low-accesscriteria including:Low-income household1. poverty rate is greater than or equal to 20 percentOR median family income does not exceed 80 percentstatewide (rural/urban) or metro-area (urban) medianfamily income;A household with income less than the Federal poverty level: 17,050 for a family of four in 2000.Rural area2. at least 500 people or 33 percent of the populationlocated more than 1 mile (urban) or 10 miles (rural)from the nearest supermarket or large grocery store.Includes areas defined by Rural-Urban Commuting Areacodes as large rural, small rural, and isolated rural areas.6Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts / ERR-140Economic Research Service/USDA

Descriptive AnalysesTract-level data from the 1990 and 2000 Census of the Population as well asfrom the 2005-2009 American Community Survey are used for populationcharacteristics. Food desert status is determined based on year 2000 population data and store location data as of 2006. At the time of this report, fooddesert status has only been identified for this one year and thus is constantfrom one survey year to the next; thus the group of food desert tracts andthe group of non-food desert tracts consist of the same tracts in each surveyyear. Our analysis compares statistics for the tracts identified as food desertsbased on the 2000 Census data and 2006 store locations with statistics forother tracts. We also calculate differences in characteristics of food desertsfrom 1990 to 2000, 2000 to 2005/2009, and over the entire period andcompare these to changes in the same statistics for all other tracts. We use5-year average data from the 2005-09 ACS to provide a recent picture of thedemographics of food desert tracts.4 We conduct and present these analysesseparately for rural and urban tracts, as demographics tend to differ significantly between rural and urban areas. Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA)codes designate each tract as urban or rural.5 RUCA codes use census tractsto identify urban cores and adjacent areas that are integrated with these urbancores. Ten primary codes and 33 secondary codes are assigned based on thedesignation of areas as metropolitan or micropolitan, and high-commutingor low-commuting. We use a 4-category classification that allocates the 33RUCA secondary codes into urban, large rural, small rural, or isolated areas.6We then combine large rural, small rural and isolated areas to create a single,broad rural category.4The ACS replaces the long-formCensus after 2000 and provides muchof the same data as the DecennialCensus long form. We use the 5-yeardata as they are the only increments forwhich tract-level data are available formost variables.5For more information, see: commuting-area-codes.aspx/.6For more information, see: roup quarters typically have institutional cafeterias and retail food facilities that are not counted in our list of supermarkets and large grocery stores.Some tracts that are dominated by university, prison, or m

population, the more likely the area is to be a food desert. Residents in the Northeast are less likely to live far from a store than their counterparts in other regions of the country with similar income levels. Rural areas experiencing population growth are less