Transcription

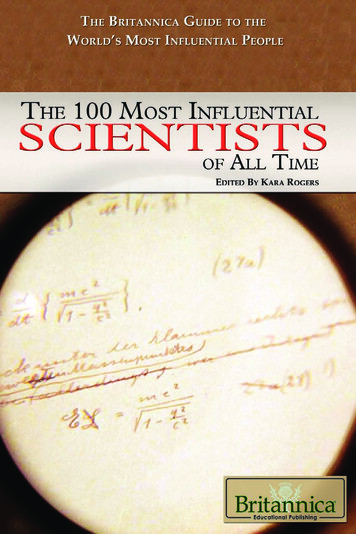

Published in 2010 by Britannica Educational Publishing(a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.)in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.Copyright 2010 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica,and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Allrights reserved.Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2010 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.All rights reserved.Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.First EditionBritannica Educational PublishingMichael I. Levy: Executive EditorMarilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production ControlSteven Bosco: Director, Editorial TechnologiesLisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data EditorYvette Charboneau: Senior Copy EditorKathy Nakamura: Manager, Media AcquisitionKara Rogers: Senior Editor, Biomedical SciencesRosen Educational ServicesJeanne Nagle: Senior EditorNelson Sá: Art DirectorIntroduction by Kristi LewLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataThe 100 most influential scientists of all time / edited by Kara Rogers.—1st ed.p. cm.—(The Britannica guide to the world’s most influential people)“In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.”Includes index.ISBN 978-1-61530-040-2 (eBook)1. Science—Popular works. 2. Science—History—Popular works. 3. Scientists—Biography—Popular works. I. Rogers, Kara. II. Title: One hundred influential scientistsof all time.Q162.A15 2010509.2'2—dc222009026069On the cover: Discoveries such as Einstein’s theory of relativity—shown in originalmanuscript form—are hallmarks of the genius exhibited by the world’s most influentialscientists. Jon Levy/AFP/Getty Images

liny the ElderPtolemyGalen of PergamumAvicennaRoger BaconLeonardo da VinciNicolaus CopernicusParacelsusAndreas VesaliusTycho BraheGiordano BrunoGalileoJohannes KeplerWilliam HarveyRobert BoyleAntonie van LeeuwenhoekRobert HookeJohn RaySir Isaac NewtonCarolus LinnaeusHenry CavendishJoseph PriestleyLuigi GalvaniSir William HerschelAntoine-Laurent LavoisierPierre-Simon LaplaceEdward JennerJohn DaltonGeorges 89397101105108112116120123126306590

Alexander von HumboldtAndré-Marie AmpèreAmedeo AvogadroJoseph-Louis Gay-LussacSir Humphry DavyJöns Jacob BerzeliusJohn James AudubonMichael FaradaySir Charles LyellLouis AgassizCharles DarwinSir Francis GaltonGregor MendelLouis PasteurAlfred Russel WallaceWilliam ThomsonJoseph ListerJames Clerk MaxwellDmitry IvanovichMendeleyevIvan Petrovich PavlovA.A. MichelsonRobert KochSigmund FreudMax PlanckNettie Maria StevensWilliam BatesonPierre CurieMarie CurieHenrietta Swan LeavittErnest RutherfordCarl JungAlbert EinsteinAlfred Lothar WegenerSir Alexander FlemingNiels 244252253256247

Erwin SchrödingerSelman Abraham WaksmanEdwin Powell HubbleLinus PaulingEnrico FermiMargaret MeadBarbara McClintockLeakey FamilyGeorge GamowJ. Robert OppenheimerHans BetheMaria Goeppert MayerRachel CarsonJacques-Yves CousteauLuis W. AlvarezAlan M. TuringNorman Ernest BorlaugJonas Edward SalkSir Fred HoyleFrancis Harry Compton CrickJames Dewey WatsonRichard P. FeynmanRosalind FranklinEdward O. WilsonJane GoodallSir Harold W. KrotoRichard E. SmalleyRobert F. Curl, Jr.Stephen Jay GouldStephen W. HawkingJ. Craig VenterFrancis CollinsSteven PinkerGlossaryFor Further 30332335337339341343296307330

INTRODUCTION

7Introduction7In science the credit goes to the man who convinces the world,not to the man to whom the idea first occurs.—Francis Darwin (1848–1925)From the very first moment humans appeared on theplanet, we have attempted to understand and explainthe world around us. The most insatiably curious amongus often have become scientists.The scientists discussed in this book have shapedhumankind’s knowledge and laid the foundation for virtually every scientific discipline, from basic biology to blackholes. Some of these individuals were inclined to ponderquestions about what was contained within the humanbody, while others were intrigued by celestial bodies. Theircollective vision has been concentrated enough to examine microscopic particles and broad enough to unlocktremendous universal marvels such as gravity, relativity—even the nature of life itself. Acknowledgement of theirimportance comes from a variety of knowledgeable andwell-respected sources; luminaries such as Isaac Asimovand noted biochemist Marcel Florkin have written biographies contained herein.The influence wielded by the profiled men and womenwithin the realm of scientific discovery becomes readilyapparent as the reader delves deeper into each individual’slife and contributions to his or her chosen field. Oftentimes,more than one field has been the beneficiary of these brilliant minds. Many early scientists studied several differentbranches of science during their lifetimes. Indeed, as thefounder of formal logic and the study of chemistry, biology, physics, zoology, botany, psychology, history, andliterary theory in the Middle Ages, Aristotle is consideredone of the greatest thinkers in history.Breakthroughs in the medical sciences have beennumerous and extremely valuable. Study in this discipline9

7 The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time7begins with a contemporary of Aristotle’s namedHippocrates, who is commonly regarded as the “father ofmedicine.” Perhaps Hippocrates’ most enduring legacy tothe field is the Hippocratic Oath, the ethical code thatdoctors still abide by today. By taking the HippocraticOath, doctors pledge to Asclepius, the Greco-Roman godof medicine, that to the best of their knowledge and abilities, they will prescribe the best course of medical care fortheir patients. They also promise to, above all, cause noharm to any patient.The Greeks were not the only ones studying medicine. The Muslim scholar Avicenna also advanced thediscipline by writing one of the most influential medicaltexts in history, The Canon of Medicine. Avicenna also produced an encyclopedic volume describing Aristotle’sphilosophic and scientific thoughts about logic, biology,psychology, geometry, astronomy, music, and metaphysics. This hefty tome was called the Kitāb al-shifā (“Book ofHealing”). About 450 years later, a German-Swiss physician named Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus BombastusVon Hohenheim, or Paracelsus, once again advancedmedical science by integrating medicine with chemistryand linking specific diseases to medications that couldtreat them.The Renaissance period brought to light the scientificgenius of painter and sculptor Leonardo da Vinci. Hisdrawings of presciently detailed flying machines precededthe advent of human flight by more than 300 years. What’smore, da Vinci’s drawings of the human anatomy structure not only illuminated many of the body’s features andfunctions, they also laid the foundation for modern scientific illustration.Anatomical drawings were also the purview of Flemishphysician Andreas Vesalius. Unlike da Vinci’s illustrations,10

7Introduction7which were mainly for his own artistic education, Vesaliusincorporated his sketches and the explanations of theminto the first anatomy textbook. His observations ofhuman anatomy also helped to advance physiology, thestudy of the way the body functions.Other physicians took their investigation of anatomyoff the page and onto the operating table. Ancient Greekphysician Galen of Pergamum greatly influenced the studyof medicine by performing countless autopsies on monkeys, pigs, sheep, and goats. His observations allowed himto ascertain the functions of the nervous system and notethe difference between arteries and veins. Galen was alsoable to dispel the notion that arteries carry air, an idea thathad persisted for 400 years.Centuries later, in the 1600s, Englishman WilliamHarvey built on Galen’s theories and observations, andhelped lay the foundation for modern physiology with hisnumerous animal dissections. As a result of his work,Harvey was the first person to describe the function of thecirculatory system, providing evidence that veins andarteries had separate and distinct functions. Before hisrealization that the heart acts as a pump that keeps bloodflowing throughout the body, people thought that constrictions of the blood vessels caused the blood to move.Other groundbreaking scientists have relied on observations outside the body. A gifted Dutch scientist and lensgrinder named Antonie van Leeuwenhoek refined themain tool of his trade, the microscope, which allowed himto become the first person to observe tiny microbes.Leeuwenhoek’s observations helped build the frameworkfor bacteriology and protozoology.As several of the stories in this book confirm, scienceis a competitive yet oddly cooperative field, with researchers frequently either refuting or capitalizing on one11

7 The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time7another’s findings. Some ideas survive the test of time andremain intact while others are discarded or changed to fitmore recent data. As an example of the former, Sir IsaacNewton developed three laws of motion that are still thebasic tenets of mechanics to this day. Newton also provedinstrumental to the advancement of science when heinvented calculus, a branch of mathematics used by physicists and many others.Then there are the numerous advances made in thename of science that began with the development of vaccines. Smallpox was a leading cause of death in 18th-centuryEngland. Yet Edward Jenner, an English surgeon, noticedsomething interesting occurring in his small village. Peoplewho were exposed to cowpox, a disease contracted frominfected cattle that had relatively minor symptoms, didnot get smallpox when they were exposed to the disease.Concluding that cowpox could protect people from smallpox, Jenner purposely infected a young boy who lived inthe village first with cowpox, then with smallpox.Thankfully, Jenner’s hypothesis proved to be correct. Hehad successfully administered the world’s first vaccine anderadicated the disease.More than fifty years later, another scientist by thename of Louis Pasteur would expand Jenner’s ideas byexplaining that the microbes, first discovered byLeeuwenhoek, caused diseases like smallpox. Today thisidea is called the germ theory. Pasteur would go on to discover the vaccines for anthrax, rabies, and other diseases.He also came to understand the role microbes played inthe contamination and spoilage of food. The process heinvented to prevent these problems, known as pasteurization, is still in use today.Other scientists, including Joseph Lister, RobertKoch, Sir Alexander Fleming, Selman Waksman, and12

7Introduction7Jonas Salk, would build on Pasteur’s germ theory, leadingto subsequent discoveries of medical import. Anyonewho ever needs to have an operation has Lister, thefounder of antiseptic medicine, to thank for today’s sterile surgical techniques. Koch, with his numerousexperiments and meticulous record keeping, was instrumental in advancing the idea that particular microbescaused particular illnesses, greatly improving diagnosticmedicine. Fleming was responsible for discovering thefirst antibiotic, penicillin, in 1928. Fleming’s work wascontinued by Waksman, who systematically searched forother antibiotics. This led to the discovery of one of themost widely used antibiotics of modern times, streptomycin, in 1943. Less than 10 years later, Salk woulddevelop a vaccine that could protect children from thedebilitating and deadly disease poliomyelitis. Since thattime, scientists have almost succeeded in eliminatingpolio worldwide.Medical scientists are certainly not the only ones tobuild on one another’s work. Discoveries of one scientist,no matter what field he or she works in, are almost alwaysexamined, recreated, and expanded on by others. LuigiGalvani, an Italian physicist and physician, for example,discovered that animal tissue (specifically frog legs) couldconduct an electric current. Building on Galvani’s observations, his friend, Italian scientist Alessandro Volta,constructed the first battery in 1800.Expanding on Volta’s work and that of Danish physicist Hans Christiaan Ørsted, who discovered thatelectricity running through a wire could deflect a magneticcompass needle, French physicist André-Marie Ampèrefounded a new scientific field called electromagnetism.The English physicist Michael Faraday would pick up thework from there, using a magnetic field to produce an13

7 The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time7electric current. In turn, this enabled him to invent andbuild the first electric motor.Reviewing Faraday’s experiments and theoretical workallowed James Clerk Maxwell to unify the ideas of electricity and magnetism into an electromagnetic theory andto mathematically describe the electromagnetic force.Another physicist, Albert Michelson, determined that thespeed of light was a never-changing constant. UsingMaxwell’s mathematical theories and Michelson’s experimental data, Albert Einstein was able to develop his specialtheory of relativity, which resulted in what is arguably themost famous equation in the world: E mc2. This elegantlysimple but extremely powerful equation states that massand energy are two different forms of the same thing. Inother words, they are interchangeable. This idea has beenindescribably important to the development of modernphysics and astronomy.Einstein suggested that his idea could be tested usingradium, a radioactive element discovered shortly beforehe announced his special theory of relativity. Discoveredby Marie Curie, a Polish-born French chemist, and herhusband, Pierre, radium continuously converts some of itsmass into energy, a process Madame Curie named radioactivity. Her studies would eventually result in her becomingthe first woman to ever be awarded a Nobel Prize. She wasawarded a second Nobel Prize in 1911 for the discovery ofpolonium and radium.Building on the work of Curie and Einstein, future scientists would be successful—for better or worse—inharnessing nuclear energy. These concepts would be usedto build fission reactors in nuclear power plants, producing electricity for towns and cities. However, the sameconcepts would also be used by a group of scientists,including Enrico Fermi, J. Robert Oppenheimer, LuisAlvarez, and many others, to develop nuclear weapons.14

7Introduction7In 1675, Isaac Newton wrote a letter to Robert Hookein which he said, “If I have seen further it is by standingon the shoulders of giants.” Thanks to the pioneeringefforts of the scientists mentioned in this introduction,along with the other chemists, biologists, astronomers,ecologists, and geneticists in the remainder of this book,today’s scientists have a solid foundation upon which tomake astounding leaps of logic. Without the work ofthese men and women, we would not have computers,electricity, or many other modern conveniences. Wewould not have the vaccines and medications that helpkeep us healthy. And, in general, we would know a lot lessabout the way the human body functions and the way theworld works.Today’s scientists owe a huge debt of gratitude to thescientists of days past. By standing on the shoulders ofthese giants, who knows how far they may be able to see.15

7 Asclepius7ASCLEPIUSIn the Iliad, the writer Homer mentions Asclepius only asa skillful physician and the father of two Greek doctorsat Troy, Machaon and Podalirius. In later times, however,he was honoured as a hero, and eventually worshiped as agod. Asclepius (Greek: Asklepios, Latin: Aesculapius), theson of Apollo (god of healing, truth, and prophecy) andthe mortal princess Coronis, became the Greco-Romangod of medicine. Legend has it that the Centaur Chiron,who was famous for his wisdom and knowledge of medicine, taught Asclepius the art of healing. At length Zeus,the king of the gods, afraid that Asclepius might render allmen immortal, slew him with a thunderbolt. Apollo slewthe Cyclopes who had made the thunderbolt and was thenforced by Zeus to serve Admetus.Asclepius’s cult began in Thessaly but spread to manyparts of Greece. Because it was supposed that Asclepiuseffected cures of the sick in dreams, the practice of sleeping in his temples in Epidaurus in South Greece becamecommon. This practice is often described as Asclepianincubation. In 293 BCE his cult spread to Rome, where hewas worshiped as Aesculapius.Asclepius was frequently represented standing, dressedin a long cloak, with bare breast; his usual attribute was astaff with a serpent coiled around it. This staff is the onlytrue symbol of medicine. A similar but unrelated emblem,the caduceus, with its winged staff and intertwined serpents, is frequently used as a medical emblem but iswithout medical relevance since it represents the magicwand of Hermes, or Mercury, the messenger of the godsand the patron of trade. However, its similarity to the staffof Asclepius resulted in modern times in the adoption ofthe caduceus as a symbol of the physician and as theemblem of the U.S. Army Medical Corp.17

7 The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time7The plant genus Asclepias, which contains variousspecies of milkweed, was named for Asclepius. Many ofthese plants possess some degree of medicinal value.Hippocrates(b. c. 460 BCE, island of Cos, Greece—d. c. 375 BCE, Larissa, Thessaly)Hippocrates was an ancient Greek physician who livedduring Greece’s Classical period and is traditionallyregarded as the father of medicine. It is difficult to isolatethe facts of Hippocrates’ life from the later tales told abouthim or to assess his medicine accurately in the face of centuries of reverence for him as the ideal physician. About60 medical writings have survived that bear his name,most of which were not written by him. He has beenrevered for his ethical standards in medical practice,mainly for the Hippocratic Oath, which, it is suspected,he did not write.Life and WorksWhat is known is that while Hippocrates was alive, hewas admired as a physician and teacher. In the ProtagorasPlato called Hippocrates “the Asclepiad of Cos,” whotaught students for fees. Further, he implied thatHippocrates was as well known as a physician as Polyclitusand Phidias were as sculptors. Plato also referencedHippocrates in the Phaedrus, in which Hippocrates isreferred to as a famous Asclepiad who had a philosophicalapproach to medicine.Meno, a pupil of Aristotle, specifically stated in his history of medicine the views of Hippocrates on the causationof diseases, namely, that undigested residues were producedby unsuitable diet and that these residues excreted vapours,which passed into the body generally and produced18

7 Hippocrates7diseases. Aristotle said that Hippocrates was called “theGreat Physician” but that he was small in stature.Hippocrates appears to have traveled widely in Greeceand Asia Minor practicing his art and teaching his pupils.He presumably taught at the medical school at Cos quitefrequently. His reputation, and myths about his life andhis family, began to grow in the Hellenistic period, about acentury after his death. During this period, the Museumof Alexandria in Egypt collected for its library literarymaterial from preceding periods in celebration of the pastgreatness of Greece. So far as it can be inferred, the medical works that remained from the Classical period (amongthe earliest prose writings in Greek) were assembled as agroup and called the works of Hippocrates (CorpusHippocraticum).The virtues of the Hippocratic writings are many, and,although they are of varying lengths and literary quality,they are all simple and direct, earnest in their desire tohelp, and lacking in technical jargon and elaborate argument. The works show such different views and styles thatthey cannot be by one person, and some were clearly written in later periods. Yet all the works of the Corpus sharebasic assumptions about how the body works and whatdisease is, providing a sense of the substance and appeal ofancient Greek medicine as practiced by Hippocrates andother physicians of his era. Prominent among these attractive works are the Epidemics, which give annual records ofweather and associated diseases, along with individualcase histories and records of treatment, collected fromcities in northern Greece. Diagnosis and prognosis arefrequent subjects.Other treatises explain how to set fractures and treatwounds, feed and comfort patients, and take care of thebody to avoid illness. Treatises called Diseases deal withserious illnesses, proceeding from the head to the feet,19

7 The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time7giving symptoms, prognoses, and treatments. There areworks on diseases of women, childbirth, and pediatrics.Prescribed medications, other than foods and local salves,are generally purgatives to rid the body of the noxious substances thought to cause disease. Some works argue thatmedicine is indeed a science, with firm principles andmethods, although explicit medical theory is very rare.The medicine depends on a mythology of how the bodyworks and how its inner organs are connected. The mythis laboriously constructed from experience, but it must beremembered that there was neither systematic researchnor dissection of human beings in Hippocrates’ time.Hence, while much of the writing seems wise and correct,there are large areas where much is unknown.Over the next four centuries, imaginative writings,some obviously fiction, were added to the original collection of Hippocratic works and enhanced Hippocrates’reputation, providing the basis for the traditional pictureof Hippocrates as the father of medicine. Still other workswere added to the Hippocratic Corpus between its firstcollection and its first scholarly edition around the beginning of the 2nd century CE. Among them were theHippocratic Oath and other ethical writings that prescribe principles of behaviour for the physician.Hippocratic OathThe Hippocratic Oath dictates the obligations of thephysician to students of medicine and the duties of pupilto teacher. In the oath, the physician pledges to prescribeonly beneficial treatments, according to his abilities andjudgment; to refrain from causing harm or hurt; and tolive an exemplary personal and professional life. The textof the Hippocratic Oath (c. 400 BCE) provided below isa translation from Greek by Francis Adams (1849). It is20

7 Hippocrates7considered a classical version and differs from contemporary versions, which are reviewed and revised frequentlyto fit with changes in modern medical practice.I swear by Apollo the physician, and Aesculapius, andHealth, and All-heal, and all the gods and goddesses, that,according to my ability and judgment, I will keep this Oathand this stipulation—to reckon him who taught me this Artequally dear to me as my parents, to share my substance withhim, and relieve his necessities if required; to look upon hisoffspring in the same footing as my own brothers, and toteach them this Art, if they shall wish to learn it, without feeor stipulation; and that by precept, lecture, and every othermode of instruction, I will impart a knowledge of the Art tomy own sons, and those of my teachers, and to disciples boundby a stipulation and oath according to the law of medicine,but to none others. I will follow that system of regimenwhich, according to my ability and judgment, I consider forthe benefit of my patients, and abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous. I will give no deadly medicine toany one if asked, nor suggest any such counsel; and in likemanner I will not give to a woman a pessary to produceabortion. With purity and with holiness I will pass my lifeand practice my Art. I will not cut persons laboring underthe stone, but will leave this to be done by men who are practitioners of this work. Into whatever houses I enter, I will gointo them for the benefit of the sick, and will abstain fromevery voluntary act of mischief and corruption; and, furtherfrom the seduction of females or males, of freemen and slaves.Whatever, in connection with my professional practice ornot, in connection with it, I see or hear, in the life of men,which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge,as reckoning that all such should be kept secret. While I continue to keep this Oath unviolated, may it be granted to meto enjoy life and the practice of the art, respected by all men,21

7 The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time7in all times! But should I trespass and violate this Oath, maythe reverse be my lot!InfluenceTechnical medical science developed in the Hellenisticperiod and after. Surgery, pharmacy, and anatomyadvanced; physiology became the subject of serious speculation; and philosophic criticism improved the logic ofmedical theories. Competing schools in medicine (firstEmpiricism and later Rationalism) claimed Hippocratesas the origin and inspiration of their doctrines. For laterphysicians, Hippocrates stood as the inspirational source,and today Hippocrates still continues to represent thehumane, ethical aspects of the medical profession.Aristotle(b. 384 BCE, Stagira, Chalcidice, Greece—d. 322 BCE, Chalcis, Euboea)Aristotle (Greek: Aristoteles) was an ancient Greekphilosopher and scientist, and one of the greatestintellectual figures of Western history. He was the authorof a philosophical and scientific system that became theframework and vehicle for both Christian Scholasticismand medieval Islamic philosophy. Aristotle’s intellectualrange was vast, covering most of the sciences and many ofthe arts, including biology, botany, chemistry, ethics, history, logic, metaphysics, rhetoric, philosophy of mind,philosophy of science, physics, poetics, political theory,psychology, and zoology. He was the founder of formallogic, devising for it a finished system that for centurieswas regarded as the sum of the discipline. Aristotle alsopioneered the study of zoology, both observational andtheoretical, in which some of his work remained unsurpassed until the 19th century. His writings in metaphysics22

7 Aristotle7This statue of Aristotle, the Greek philosopher who taught Alexander theGreat, stands in the Palazzo Spada in Rome. Popperfoto/Getty Images23

7 The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time7and the philosophy of science continue to be studied, andhis work remains a powerful current in contemporaryphilosophical debate.Physics and MetaphysicsAristotle divided the theoretical sciences into threegroups: physics, mathematics, and theology. Physics as heunderstood it was equivalent to what would now be called“natural philosophy,” or the study of nature; in this sense itencompasses not only the modern field of physics but alsobiology, chemistry, geology, psychology, and even meteorology. Metaphysics, however, is notably absent fromAristotle’s classification; indeed, he never uses the word,which first appears in the posthumous catalog of his writings as a name for the works listed after the Physics. Hedoes, however, recognize the branch of philosophy nowcalled metaphysics. He calls it “first philosophy” anddefines it as the discipline that studies “being as being.”Aristotle’s contributions to the physical sciences areless impressive than his researches in the life sciences. Inworks such as On Generation and Corruption and On theHeavens, he presented a world-picture that included manyfeatures inherited from his pre-Socratic predecessors.From Empedocles (c. 490–430 BCE) he adopted the viewthat the universe is ultimately composed of different combinations of the four fundamental elements of earth,water, air, and fire. Each element is characterized by thepossession of a unique pair of the four elementary qualities of heat, cold, wetness, and dryness: earth is cold anddry, water is cold and wet, air is hot and wet, and fire is hotand dry. Each element also has a natural place in an orderedcosmos, and each has an innate tendency to move towardthis natural place. Thus, earthy solids naturally fall, while24

7 Aristotle7fire, unless prevented, rises ever higher. Other motions ofthe elements are possible but are considered “violent.” (Arelic of Aristotle’s distinction is preserved in the modernday contrast between natural and violent death.)Aristotle’s vision of the cosmos also owes much toPlato’s dialogue Timaeus. As in that work, the Earth is at thecentre of the universe, and around it the Moon, the Sun,and the other planets revolve in a succession of concentriccrystalline spheres. The heavenly bodies are not compounds of the four terrestrial elements but are made up ofa superior fifth element, or “quintessence.” In addition, theheavenly bodies have souls, or supernatural intellects,which guide them in their travels through the cosmos.Even the best of Aristotle’s scientific work has nowonly a historical interest. The abiding value of treatisessuch as the Physics lies not in their particular scientificassertions but in their philosophical analyses of some ofthe concepts that pervade the physics of different eras—concepts such as place, time, causation, and determinism.Philosophy of ScienceIn his Posterior Analytics, Aristotle applies the theory of thesyllogism (a form of deductive reasoning) to scientific andepistemological ends (epistemology is the philosophy ofthe nature of knowledge). Scientific knowledge, he urges,must be built up out of demonstrations. A demonstrationis a particular kind of syllogism, one whose premises canbe traced back to principles that are true, necessary, universal, and immediately intuited. These first, self-evidentprinciples are related

As several of the stories in this book confirm, science is a competitive yet oddly cooperative field, with research-ers frequently either refuting or capitalizing on one 7 Introduction 7. 7 The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time 7 12 an