Transcription

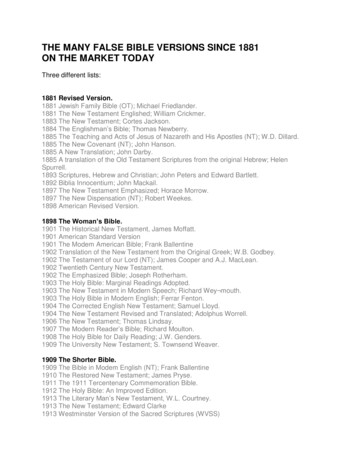

Living inside the Bible (Belt)Author(s): Shannon CarterReviewed work(s):Source: College English, Vol. 69, No. 6 (Jul., 2007), pp. 572-595Published by: National Council of Teachers of EnglishStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25472240 .Accessed: 22/01/2012 02:34Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at ms.jspJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.National Council of Teachers of English is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toCollege English.http://www.jstor.org

572Livinginside the Bible (Belt)ShannonTeachingCarterwriting in the Bible Belt for the past five years has taughtme a number of things.Most significantly, perhaps?as much as I hate to admit?it hastaughtme the limits ofmy own tolerance for difference. In fact, the evangelical Christianity with which a number ofmy studentsmost identifyfunctions?rhetorically, ideologically, practically?in ways that appear completely and irreconcilably at odds with my pedagogical and scholarly goals. The social and culturaltheories with which I most identify celebrate difference both empathically and explicitly, yet much of the traditional conservatism through which evangelical Christianity1resonates seems to embrace familiarity above all else, representing differencenot as a benefit to embrace and learn from but as a threat to overcome (see Kintz). Akeyobjectiveof ssof one'ssubject position and the partial and socially situated nature of one's understanding ofthe goal of "witnessing talk" or "testimonial" appears to bethe world. However,quite the opposite: to "convert" the listener to the speaker's ways of knowing andathe speaker'sliving, conversion completely dependent upon the acceptance thatown subject position is farfrom "partial" or "socially situated" but rather universal,right,and?aboveall?"True."like Amy Goodburn, Priscilla Perkins, and Lizabeth Rand, however,have identified several rather ironic parallels between the critical position with whichImost identify and theChristian position my Bible-believing studentsmay use as, inRand's words, "the primary sense of selfhood [. they] draw upon inmaking meanCriticsing of their lives and the worldaround them" (350). In comparingthe agenda ofwhere she diCarteris assistant professor of English atTexas A&M University-Commerce,rects the writing center and the basic writing program and teaches basic writing and graduate courses inLives: Rhetorical Dexterity and the "Basic"Writer (forthcomposition theory. She is author of The Way LiteracyBasic Writing.inandarticlesforthcomingCollege Composition and Communication and theJournal ofcoming)on College Compositionand Communicationof this article was given at the 2006 ConferenceAversionShannonmeeting.College English, Volume69, Number6, July 2007

Living insidetheBible (Belt)critical education with that of a Christian witnessing forChrist, for example, Randsuggests that both "act as witnesses hoping to convert others to the faith" (360).a blindaAccording to the former, "evil" results from lack of critical consciousness,faith in individualism and themyth ofmeritocracy that ignores the function of comour lifepaths; according to the latmunity and material conditions in determiningtothe centre of our world," urlifeinGod'softhe functionpath (Taylor, qtd. in Rand 360).determiningplanoutis that both "desire to convertAmong themany similarities Goodburn pointsthe'other,'topersuadethosewhomtheydefineas either'unsaved'or'uncritical'"(348). As my neighbor put itonce after returning from a trip to India with theChurchof Christ, the ultimate goal of his missionary work there was "to save [them] fromthemselves." So, too, it seems my goal as an educator2 has often been to "save" myopenly religious students "from themselves."Despite the surprising number of similarities betweenthese communities ofpractice, however, the fact remains thatmany evangelical students find the academyto be openly hostile to their faith-based ways of knowing, being, and expressingevangelical discourse seems openly hostile to alreadyexmarginalized groups (homosexuals, women, those of non-Christian faiths, forstudyample). For Luke, the Christian student who was the subject of Goodburn'scited earlier, "valuing difference in perspectives leads to tolerating those whoseunlifestyleshe finds irreconcilable with his religious beliefs. To tolerate differenceanmusttobe saved in orderindividualbe accepted" (346). Asdermines his faith thatthemselves. Likewise, muchLuke himself put it in a taped interview, "I don't need the university tellingme thatI should tolerate everybody [. . .] because not everybody's tolerable!" (qtd. inGoodburn346).It is a gap that liberal academics and evangelical Christians may find impossibleto traverse?intolerable,in fact.Chris Anderson tells us that that "as academics, it'stime thatwe were more aware that our position is not beyond point of view" (20).recently, Priscilla Perkins asserts that "teachers write off evangelical studentsmuch too quickly." She suggests that instead we teach evangelical students to "put[their] reading[s] of the Bible into dialogue with sometimes competing, sometimesMorecomplementary sources of secular, academic knowledge" via "an explicitly hermeneutical approach" (586). Contributors to the recent collectionNegotiating ReligiousFaith in theComposition Classroom address the disconnect between theacademy andtotousefaithstudents"learntensionbetweenfaith [. . .]religiousby encouragingand academic inquiry as away of learning more and learning better" (Vander Lei 8).Goodburnsuggests we might best negotiate the gap bymaking use ofwhat she seesas "the common thread between the discourses," which is "thelanguage of socialcritique" (334); Rand contends that "we should invite students to explain why [. .][evangelical] discourse has had such significance in their lives" (364).573

574College EnglishI argue that inasmuch as these believers "live in a world always already biblically written" (Kintz) and large segments of the academy are likely to remain hostileto faith-based ways of knowing, we would do better to help students speak to andacross difference by employing what I have called elsewhere a pedagogy of rhetorical dexterity,3 an approach that trains writers to effectively read, understand, manipulate, and negotiate the cultural and linguistic codes of a new community ofbased on a relatively accurate assessment of another,practice (Lave andWenger)more familiar one. That familiar community of practice may be one associated withoror "work" (like"play" (like fantasy footballquilting),plumbing or computer proas I will explore here, one's faith (perhaps evangelical Chrisoreven,gramming),I agree that it is important for such students, as Rand suggests, totianity).While"examine the reasons evangelical discourse has had such significance in their lives,"I believe rhetorical dexteritymay be ofmore immediately practical value to studentsas it explicitly asks them to think of literacy in termsmore conducive tomaintainingboth their faith-based and their academic literacies without being required to substitute one for the other. Rand suggests that our questions for students "might indoes the struggle to overcome sin affectyour life and the decisions youmake about yourself or others?" and, perhaps, "How are you limited in your undercan certainly see how responding to such quesstanding ofTruth?" (353). Though Itionsmight generate in our religious students the critical consciousness we desire, Ican also see how some students (like Luke) might feel compelled to generate responses more defensive than reflective.Moreover, as so many of my students haveclude: Howsaid, true faith is a "feeling" that cannot be explained, so articulating the reasoningbehind one's faith in terms the secular world can understand may seem impossible.As Chris Anderson puts it, faith is "a leap that cannot be justified to anyone whohasn't made that leap," making "religious experience [. . .] like a difficult language"(22, 26).In the rest of this essay, I attempt to articulate the ways inwhich rhetoricalour students to use literacies they already possess (like deepdexteritymight enableand its applications in day-to-day life) to negotiate those thetheBibleofknowledgea basic writer forwhom, atacademy expects them to exhibit. I begin with "James,"leastwithin his first semester of college, the Bible represented his primary sense of"selfhood." In thatmuch of the current argument rests on the tensions between aand one that is often perceived tocommunity of practice that "lives inside the Bible"be openly hostile to it, I continue with the stories of two graduate students in ourtheir reliprogram who?thoughtheywere able to maintain deep ties with bothsomeratheracademicandtheirpainful lesones?experiencedgious communitiestheandsons early on about the irreconcilability of Christianityacademy. Theat conservative and evangelical literaciesafollowing section takes much closer lookas articulated in public discourse within and beyond the academy. Given the com

Living insidetheBible (Belt)maneuversandthat conservativesplex political, rhetorical, and intellectualto defend the levangelicalswe would do well to understand thetobeperceivedthreatening,conflicting epistein fact, often quite real?threat. Academics,that fuel this perceived?and,us in the humanities and social sciences, appear tomany conthoseofparticularlyservative and evangelical leaders as promoting agendas of "secular humanism" andmologies"cultural relativism," agendas they view as antithetical to their own position. Building on the tensions and the conservative rhetoric that exposes these, I then return toour class's attention to "literacy" and my regular attempts toJames, who?despitevalidate his Christian literacies?still found this biblical worldview slipping awayfrom him. I end by discussing what I thinkmay have contributed to this loss andhow a pedagogy of rhetorical dexteritymight have helped James "learn to use tensions between faith [.] and academicing better" (Vander Lei 8).inquiry as a way of learning more and learnacrossCommunicatingDifferenceI asked students in a basic writing class two years ago to describe an objectthat best represented literacy for them, James started with what seemed most obvious to him: the Bible.WhenBefore I was [just]a childthatwent to church.I believed theBible was somethingyousure that you wereto heavenifyou weren't[.] so I never read it. But onegoinga child that went to church to ato matureIfromstartedI started todaychurchly child.readunderstand the older Christians and the purpose of being a Christian and the rolethat theBible played in a Christian's life.All because one day [.] I felt itwas my jobto bethe clown.[. . When.]my mother[.] saw meactinglike a foolshe cameslappedme in the back of the head in frontof allmy friendsandmaid [sic]me go tothe front of the churchbecausethe oldto sit withladies wouldn'tthe seniorletmebecausesaints.[.they would.even fall.] I couldn'tasleepeither pinch to wake me orbe making to [sic]much noise praising theLord so I had to listento themessage. [.]I meantime.Ithe Messagebut I actuallyget me wrongalways heard. That'show the front pue [sic] saved my life,.](emphasis mine)don't[.listenedthatsemester, James taughtme the difference between "a child that goes to church"and "a churchly child"?anemotional shift as profound for him as it is valuable tothe other "churchly" members of his "House." He was, however,surprised to hearthat anyone could be so confused about what that differencemight be, and itwasafterseveraltowithhimhethatunderstand the disconnect Ionlymeetingsbeganexperienced in reading his essays because ofmy own illiteracies in that communityof practice. As James explained it tome when we met inmy office to discuss revisions of the previous essay:That575

576College EnglishIt's like this.A childwhojust goes tochurchis an illiterateChristian because he can't/ee/it.He may feel something somewhere else, like in schoolwith his friendsor atwork,but that feeling ain't theLord because he's not inhisHouse. A churchlychild,though,he [is] literatebecause he canfeel it.Like I felt it.From him, I learned that "living inside the Bible" the rightway is a "feeling" thatcan "save" a person's life,but it is also a perspective that can be understood andtrulyappreciated only by others who have likewise experienced the "Message" in thisway, a feeling that only other literate Christians can experience or understand andone that is central towho the person is?in the classroom, in the church, at home?andeverywhere, in fact. It is a feeling intimately connected with "the Lord's House"one the person can "stay close to" only by reading the Bible?abook that, as manyhave found, is largely unwelcome in the academy.In our rural East Texas university, graduate students are often no less likely toon a "spiritual identity as the primary source of selfhood." However, as Englishrelycareers the disgraduate students "Alex" and "Mona" explain, early in their collegeconnect between the same Bible-basedreasoning with which theymost identify andthat Bible-based reasoning was received forced them tothe hostile ways inwhichkeep their Bible-believingidentities "in check." These painful experiences taughtthem the impossibility of revealing their lives lived "inside the Bible" in terms legible to readers unconvinced of the Bible's "infallibility" (or even of its relevance tocontexts extending beyond the churches that reproduce its value). This process isnever easy, I am told, and manyin academicroleartificialcontexts.such students believe themselves to be playing anMoreover,as Alexand Monataught me,an awareness of the negative ways inwhich the Bible is viewed in the academy is often hardwon.Alex, a PhD student inEnglish who "for the past fifteen years" has been "conain justtinuously enrolled in school" (completing high school year early and her BAtwo years) has experienced this dissonance rather sharply and consistently, despite(or perhaps because of) her ambition and intelligence: "I grew up in a SouthernI was four,my bass-playing father changed his lifefromBaptist family [.]. Whenone of rock and roll at smoky night clubs to Black Gospel on Sunday mornings."From that point on, as Alex describes it,her "religious family functioned as either aor a cult [. .] I'm not sure which one."disconnect Alex experienced between the tacit expectations of the Baptistchurch and more secular ones was vast, but itwas also a dissonance necessitated bywell-oiled machineTheher faith.As she explains,BecausesentChristianstoand I wereto go into the worldof the unsaved, my cousins. .to set awereweanwhereunsaved.]good[,alwaysplaceus anfor witnessingteachers and peers. Schoolopportunityprovidedareschoolspublicfor ourexampleand possibleconversions;whenwe werethe time came, we wouldusetold to carry a Bible withit to help others becomeus to schoolsaved.dailyso that

Living insidetheBible (Belt)But though her Bible was verymuch a part of her family,her church, and in fact hersense of self, she learned ratherquickly thatwithin many communities of practice inthe academy, itsuse is strictly forbidden.I turnedOncein a paperin whichI usedBiblicalas anpassagesargument.I failed.Aftermeeting with the teacher,I got the feeling that the reason I failed came directlyfrommy choice toquote theBible. I did nothing but remove thequotes andmy paperreceivedan "A." Evenin apersonalopinionpaper,I wasnotto useallowedevidencethat appealed tome. I am outraged by this incident to thisday.the insensitivity of her professor's actions, however, Alex persevered, beavery successful undergraduate English major and, now, a top graduatecomingstudent.Much of her ability to, in her words, "mesh my faith-based religious viewsDespitewith myfact-basedview of the world"academiccan be attributedto herhyperawareness of context. This is an ability, as Deborah Brandt puts it, to "amalgamate new reading and writing practices in response to rapid social change" ("Accumulating" 651).An evangelical Christian herself, graduate student "Mona" articulates a similarpoint of dissonance between her faith and her schooling: "I was in a class severalyears ago when the instructor-led discussion drifted to the origin ofmankind." There,she witnessed a fierce but rather empty debate between the professor and two students, the former dismissing creationism as "myth," the latter dismissing evolutioninmany of the same ways?neither,according toMona,speaking with any real understanding of the opposition's argument but obviously relying on, as she explains,"what they'd been told by others." Still, believing the professor to be "a man ofcritical thinking and open-mindedness,"she "approached him after class."Insteadof listeningand discussing,however,he dismissedmeand myargumentsbytellingme that theBible is to be viewed like ancientGreek mythology [.]. I said nomore,muchbut realizedmorethat myin commonacademicthanprofessorthey realized.and myEvangelicalstudentpeershadironic and largely unconscious?similaritiesbetweenDespite themany?sometimesthese two communities of practice, however, the dissonance remains. And, likeMona,Alex iswell aware that the battle between these rather different communities ofpractice isnot her own and, in fact, that they are largely irreconcilable. Alex says, "Iunderstand that academics look at facts and evidence. However,religion ismostlyabout feeling. IfGod wanted to,He could easily give us evidence thatHe exists. IfHedid, though, believing inHim and trustingHim wouldn't be the same" (emphasis in original).More than twenty years ago, feminists and other social theoristsbegan treatingfeeling, emotion, and intuition as valid epistemological sites, taking seriously aspects of experience that a post-Cartesian worldview has regularly dismissed. Still,577

578College Englishevenscholarship in areas like these routinely ignores the function of faith, likelyassuming it to be "anti-intellectual," "closed-minded," or even counterproductive.Faith does not seem knowledge, but rather its complete opposite.LivinginsidetheBibleIn evangelical Christianity, the Bible serves as the primary source from which thepower of familiarity resonates. As Linda Kintz explains, in this community of practice all "legitimate participants [.] live [.] inside aworld of textual quotations andreferences to biblical passages, interpretations, and reinterpretations among a com.munity of believers who know all the same stories and all the same passages [. .]Liv[ing] inside the Book [.] gives believers a world always already biblically written" (33). Given that somany ofmy students "live inside the Book," it should not besurprising that some rely on the Bible and its teachings tomake their arguments.However, the function of the college composition classroom seems to be, at the veryleast, to enable them to speak to readers who do not, likewise, "live inside the Book":readers likeme, for instance. The goal of witnessing talkmay be to "save" the listener so he or she will, likewise, "live inside the Book";4 however, this is not anappropriate aim for academic rhetoric, whose goal is often pluralism. Inasmuch as,for our most religious students, this "biblically written" world is the one with whichtheymost identify, it seems productive forus to ask that they think ofwhat it takes tobe considered literate within that world. To articulate this position would not requirewritersto herelieven vice versa) but rather to help those not "Christian-literate"gious one (orunderstand what it takes to be considered a literatemember of the biblically writtenworld. To articulate this position would require writers to think of literacy msthan mostcommonsense,schoolbased versions of literacy allow.Understandingliteracy as social rather than alphabetic, situated rather thanuniversal, and multiple rather than singular requires writers to consider themselvesto be simultaneously literate and illiterate in a number of different contexts. I am,for example, literate inwriting center studies and associated contexts but largelyilliterate inmatters relating to chemistry or video games likeGrand Theft Auto. Mystudent is, of course, a deeply "literate" Mormon, but may knowdevout Mormonsome of her classmatesvery little about the Baptist communities of practice inwhichasare quite likelyIntheotherliterate.words,findings of theNew LiteracyhighlyasetnotofisStudies have proven, literacystable, portable, rule-based skills thattextsenable the user to encode and decode all"correctly," regardless of the type oftext, the conditions under whichthe text is encoded/decoded,the purpose of the

Living insidetheBible (Belt)or thesurrounding the text, the place inwhich the text is situated,experiences of the readers/writers who put the text to use. Of course, developing inour students the flexibility and critical consciousness necessary to negotiate the textstext, the peopletheywill encounter throughout college and in their lifeworlds beyond requires thatwethey begin to think of literacy in a differentway. In this process of development,treat literacy not as an abstract set of rigid standards but rather as a blend ofmutablesocial forces deeply situated in time and place.Literate practices, at least as I am seeing them here, are those sanctioned andendorsed by others recognized as literatemembers of a particular communityof practice. As in any community, the literate practices of evangelical traditions inChristianity are those sanctioned and endorsed by other literatemembers. Those of uswho are not literatemembers of this particular community of practice are less likelyto be able to tell the difference between someone who truly does "live inside theBible"(Kintz)?whatthrough themotionsJames calls "a churchly child"?and(a "child that goes to church").someone whois goingLiteracy thus becomes both a set of socially sanctioned, community-based "skills"contentandthat is validated, produced, and reproduced within that same communitycontent thus becomes sharedknowledge among members of aofandthesemembersextend, reshape, validate, invalipractice,given communitymostcontentdate, reproduce, and archive theappropriate for them and their keynewFromthisliteracies depends not on a litobjectives.perspective, developingof practice. Relevanteracylearner'sabilityto obtainautonomousskills, noronany genericcontent-knowledge, but rather on rhetorical dexterity. The latter, as I noted earlier, calls uponstudents to effectively read, understand, manipulate, and negotiate the cultural andalinguistic codes of new community of practice based on a relatively accurate assessmentof a morefamiliarone.Rhetorical dexterity relies on two overlapping theoretical traditions: theNewLiteracy Studies and activity theory. "NLS approaches," according to Brian V Street,"focus on the everyday meanings and uses of literacy in specific cultural contextsand link directly to how we understand thework of literacy in educational contexts"is primarily concerned with theway literacymanifests(417). In other words, NLSitself in various out-of-school contexts and, through thesefindings, with exposingthe artificiality and irrelevance of formal literacy education as it exists inmost inschool contexts. NLSthen redefines literacy education itself as a matter ofreadingand negotiating various contextualized forces that aredeeply embedded in identityformation, political affiliations,material and social conditions, and ideological frameworks. This theoretical framework necessarily flattens hierarchies among literacies;instead of one literacy's being inherentlymore significant or valuable than another,their respective worth is determined by appropriateness to context.579

580College EnglishIn this sense, the anti-Bible hostility Alex andMona experienced may be betteras a dispute over appropriateness, rather than as a question of whetherunderstoodas I'm (unfortunately and often) quick tothey sufferfrom "false consciousness" or,see it, outright "ignorance." The key issue becomes the ways inwhich the Biblefunctions in the communities of practice that reproduce themselves through thefamiliarity that resonates from that very same book, as well as how these activities(and the value-sets that perpetuate them) might conflict with activities and contentreproduced within university communities of practice.In any given community of practice?beit factorywork or fishing, Xerox reoror the field of composition studies?someactivitiespairmidwifery, evangelismwill be understood as appropriate and others as largely inappropriate, and most ofthese activities cannot be understood apart from the activity systeminwhich they arecarried out. Such systems are social and cultural rather than individual and objective.They aremade up of groups who sanction and endorse particular ways of doingsome results and processes as innovativethings and particular results, identifyingasothersandand valuableineffective, inappropriate, or even unaccondemningceptable.Thus Mona'sBible becomes at once an irrelevant "book ofmyths" in her colandthe "baseline source [. . .] [for all] reasoning" (Ault 210) amongclassroomlegemembers of her church. There is, of course, nothing terribly insightful about thisrevelation. However, further exploration of the specific ways the Bible functions inus understand better the comBible-believing communities of practice might helpourwhenfaceoftenstudentsthey begin to ceLike any community of practice, evangelism is organic and dynamic. Therefore, nocan capture how it is practiced by all faith traditions in allsingle representationcontexts. Even themost influential leaders of thismovement are unable to reach ato be an evangelical Christian. As New York Timesnot monoreporterMichael Luo explains, "like any dominating force, evangelism islithic." As someone completely unaffiliated with any evangelical faith tradition andI can at best offer a description of thisonly marginally involved in Catholicism,as I understand it from an extensive survey of public andofcommunitypracticeacademic discourse on evangelism written by evangelists, as well as from informalinterviews with students and colleagues who identify themselves as evangelical.6There does appear to be a set of largely universal tenets of evangelism. Accordare those that "stress the need for aing toMark Noll, "evangelical denominations"anew birth, profess faith in the Bible as a revelation fromGod, encoursupernaturalconsensusabout whatitmeans

Living insidetheBible (Belt)age spreading the gospel through missions and personal evangelism, and emphasizethe saving character of Jesus's death and resurrection" (9). Cal Thomas, a syndicatedcolumnist and self-identified spokesperson forAmerican evangelicals, offers a similar definition: "An evangelical Christian is one who believes that Jesus Christ is theSon ofGod and who has repented of sin and accepted Jesus as his or her savior.Theto share the 'good news' thatevangelical believes he has the privilege and ght go to heaven rather than hell."aiscommitment towhat many Christians call the "Great"Spreading the gospel"this community of practice, it iswidely understood that thecan be found in theGospel ofMatthew7 inwhat is considered toCommission." WithinGreat Commissionbe the "last recorded personal instruction given by Jesus to His disciples" ("Thethose "living inside the Book" and calling themselvesGreat Commission");the duty of all Christians to be to "make disciples of all theunderstandevangelicalsnations" (Matt. 28.18-20). Some evangelists argue that the Bible itself is the productof successful evangelism, with the twelve apostles chosen by Jesus functioning asasserts in the secChristianity's very first evangelists. As Robert Emerson Colemanond edition of his popular instructional text The Master Plan ofEvangelism, "theinitial objective of Jesus's plan was to enlist men who could bear witness to his lifeand carry on his work after he returned to the Father" (27).So what, then, does this "Great Commission" have to do with the disconnectJames, Alex, and Monaexperienced as they attempted to integrate the Bible intoacademic contexts? Because we are concerned with practices that replicate the comas a whole, it is useful to examinemunity, as well as with the communityevangelicala community and an activity system.According to this theoretiasbothChristianitycal framework, the "acts" of relying on the Bible forwisdom and guidance (as Jameshas) and using the Bible as evidence for a personal opinion paper (as Alex has) maybe understood as unacceptable when evaluated by the communities of practice associated with the academy, but as completely acceptable and even mandatory whenevaluated by those associated with their faith.The disconnect is profound whenexperienced by those forwhom the Bible represents their "primary sense of selfhood"and merely obvious when judged by those forwhom the Bible represents at bestnaivety and atworst "closed-mindedness" or even bigotry. The disconnect betweenthese two communities of practice is not something to be glossed over as a "given"and irreconcilable, however, as I am attempting to prove here.When attemptin

Living inside the Bible (Belt) Author(s): Shannon Carter Reviewed work(s): Source: College English, Vol. 69, No. 6 (Jul