Transcription

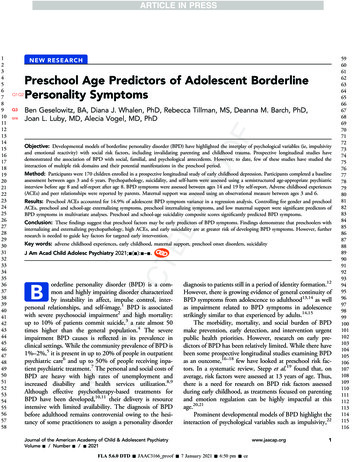

5565758N EW R E S E A R C HQ1Q2Q3Q18Preschool Age Predictors of Adolescent BorderlinePersonality SymptomsBen Geselowitz, BA, Diana J. Whalen, PhD, Rebecca Tillman, MS, Deanna M. Barch, PhD,Joan L. Luby, MD, Alecia Vogel, MD, PhDObjective: Developmental models of borderline personality disorder (BPD) have highlighted the interplay of psychological variables (ie, impulsivityand emotional reactivity) with social risk factors, including invalidating parenting and childhood trauma. Prospective longitudinal studies havedemonstrated the association of BPD with social, familial, and psychological antecedents. However, to date, few of these studies have studied theinteraction of multiple risk domains and their potential manifestations in the preschool period.Method: Participants were 170 children enrolled in a prospective longitudinal study of early childhood depression. Participants completed a baselineassessment between ages 3 and 6 years. Psychopathology, suicidality, and self-harm were assessed using a semistructured age-appropriate psychiatricinterview before age 8 and self-report after age 8. BPD symptoms were assessed between ages 14 and 19 by self-report. Adverse childhood experiences(ACEs) and peer relationships were reported by parents. Maternal support was assessed using an observational measure between ages 3 and 6.Results: Preschool ACEs accounted for 14.9% of adolescent BPD symptom variance in a regression analysis. Controlling for gender and preschoolACEs, preschool and school-age externalizing symptoms, preschool internalizing symptoms, and low maternal support were significant predictors ofBPD symptoms in multivariate analyses. Preschool and school-age suicidality composite scores significantly predicted BPD symptoms.Conclusion: These findings suggest that preschool factors may be early predictors of BPD symptoms. Findings demonstrate that preschoolers withinternalizing and externalizing psychopathology, high ACEs, and early suicidality are at greater risk of developing BPD symptoms. However, furtherresearch is needed to guide key factors for targeted early intervention.Key words: adverse childhood experiences, early childhood, maternal support, preschool onset disorders, suicidalityJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021;-(-):-–-.orderline personality disorder (BPD) is a common and highly impairing disorder characterizedby instability in affect, impulse control, interpersonal relationships, and self-image.1 BPD is associatedwith severe psychosocial impairment2 and high mortality:up to 10% of patients commit suicide,3 a rate almost 50times higher than the general population.4 The severeimpairment BPD causes is reflected in its prevalence inclinical settings. While the community prevalence of BPD is1%–2%,5 it is present in up to 20% of people in outpatientpsychiatric care6 and up to 50% of people receiving inpatient psychiatric treatment.7 The personal and social costs ofBPD are heavy with high rates of unemployment andincreased disability and health services utilization.8,9Although effective psychotherapy-based treatments forBPD have been developed,10,11 their delivery is resourceintensive with limited availability. The diagnosis of BPDbefore adulthood remains controversial owing to the hesitancy of some practitioners to assign a personality disorderBdiagnosis to patients still in a period of identity formation.12However, there is growing evidence of general continuity ofBPD symptoms from adolescence to adulthood13,14 as wellas impairment related to BPD symptoms in adolescencestrikingly similar to that experienced by adults.14,15The morbidity, mortality, and social burden of BPDmake prevention, early detection, and intervention urgentpublic health priorities. However, research on early predictors of BPD has been relatively limited. While there havebeen some prospective longitudinal studies examining BPDas an outcome,16–18 few have looked at preschool risk factors. In a systematic review, Stepp et al.19 found that, onaverage, risk factors were assessed at 13 years of age. Thus,there is a need for research on BPD risk factors assessedduring early childhood, as treatments focused on parentingand emotion regulation can be highly impactful at thisage.20,21Prominent developmental models of BPD highlight theinteraction of psychological variables such as impulsivity,22Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent PsychiatryVolume - / Number - / - 2021FLA 5.6.0 DTD JAAC3166 proof 7 January 2021 6:50 pm 00101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116

GESELOWITZ et 166167168169170171172173174175emotional sensitivity, and overreactivity23 with social riskfactors including invalidating parenting,22 disorganizedattachment,11,24 and childhood trauma.25 These biopsychosocial developmental models have been supported byprospective longitudinal studies demonstrating that BPD isassociated with social antecedents such as child abuse andneglect,26 maternal hostility,16 early life stress,27 and peervictimization.18 Psychological antecedents includingattention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms17 and infant emotionality16 and biological antecedentsincluding genetic liability14 and prenatal exposures28 havebeen reported. Family psychiatric history,29,30 which includes biological, psychological, and social components, is astrong indicator of risk. However, few studies haveaccounted for multiple risk domains simultaneously, making it difficult to determine if there is a separable role foreach of these risk factors in predicting BPD. Moreover,many of these studies are limited to the adolescent timeperiod, leaving the effects of earlier childhood psychopathology, occurring during a key period of emotional regulatory development, unexplored. Finally, while a number ofstudies use high-risk community (eg, enriched for poverty)and clinical (eg, enriched for externalizing psychopathology)samples, to our knowledge no study to date has prospectively examined BPD risk factors in a sample selected forinternalizing psychopathology ascertained in early childhood, which is also associated with impaired developmentof emotion regulation.The goal of the present study was to use longitudinaldata from a sample enriched for preschool depression toexamine the relationships between family, social, and psychological factors prospectively assessed during early childhood with adolescent BPD symptoms. Following keyfindings on predictors of BPD, we specifically examined thefollowing potential early developmental antecedents ofborderline symptoms: demographic predictors, adversechildhood experiences (ACEs), maternal support, maternalpsychopathology, childhood internalizing and externalizingpsychopathology, peer problems, and preschool suicidality(which, while unusual, has been observed in this agegroup31). We also attempted to determine the separableeffects of ACEs, maternal support, and preschool internalizing and externalizing psychopathology through a multipleregression model.METHODParticipantsParticipants were enrolled in the Preschool DepressionStudy (PDS), a prospective, longitudinal investigation ofpreschoolers and their families conducted at the2www.jaacap.orgWashington University School of Medicine EarlyEmotional Development Program that has been extensivelydescribed elsewhere.32 Initially, 306 children 3–6 years oldand their caregivers were recruited from primary care clinicsand day care centers in the St. Louis Metropolitan areaoversampling for depression using the Preschool FeelingsChecklist, a validated measure assessing depressive symptoms in preschool-age children, enrolling children with 3symptoms of depression, children with 3 symptoms ofdisruptive behavior, or children with at least 1 symptom ofeither type. All children and parents were invited toparticipate in up to an additional 6 yearly assessmentsincluding clinical interviews, observational assessments, andbehavioral questionnaires, and a subset of these children andtheir parents were invited to participate in an additional 3assessments including similar interviews and 4 neuroimaging scans, in total spanning more than 10 years. Thepresent study included 170 children who completed theBorderline Personality Features Scale for Children (BPFSC) during assessment 9 (ages 14–19 years, mean [SD] age16.0 [0.96]). The participants who completed the BPFS-C Q 4at assessment 9 were not statistically different in demographics or any of the domains of psychopathology andfunctioning assessed from participants who did not complete the ninth assessment (Table S1, available online).AssessmentsFor a composite summary of all assessments and timing ofadministration, see Table S2, available online.Demographic AssessmentsIncome-to-Needs Ratio. Income-to-needsratio wasassessed at baseline by dividing parent-reported income bythe federal poverty guideline for parent-reported number ofpeople living in the home.IQ. IQ was assessed using either the Weschler AbbreviatedScale of Intelligence Second Edition at assessment 5 (ages8–12) or the Kauffman Brief Intelligence Test SecondEdition at assessment 7 (ages 9.17–14.89). Owing to thepresumed general stability across development, IQ wasconsidered as a lifetime risk factor.Adolescent Psychopathology and OutcomeAssessmentsBorderline Symptoms. Borderline symptoms in childrenwere assessed using the BPFS-C,33 a widely used self-reportmeasure of borderline pathology with excellent criterionvalidity.34 The borderline symptoms were assessed atassessment 9 (ages 14–19). Our analyses used a continuous Q 5Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent PsychiatryVolume - / Number - / - 2021FLA 5.6.0 DTD JAAC3166 proof 7 January 2021 6:50 pm 25226227228229230231232233234

PRESCHOOL PREDICTORS OF ADOLESCENT 284285286287288289290291292293BPFS-C score as well as the standard BPFS-C cutoff score of65 for presumptive clinical diagnosis.34Psychopathology. Symptoms of major depressive disorder(MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), separationanxiety disorder (SAD), social phobia (SOC), posttraumaticstress disorder (PTSD), ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and conduct disorder (CD) were assessed atassessment 9 using the Schedule for Affective Disorders andSchizophrenia for School-Age Children (Present and Lifetime version) (K-SADS-PL),35 a reliable, semistructuredclinical interview for parents and children ages 6–18. Alldiagnoses were based on DSM-5 symptoms endorsed byeither the caregiver or the youth.Q6Impairment. At assessment 9 (ages 14–19), impairment wasassessed by the clinician-rated Children’s Global AssessmentScale (CGAS), a widely used, reliable measure of generalfunctioning in children and adolescents.36 The Health andBehavior Questionnaire (HBQ), a reliable and valid parentreport measure of overall impairment, academic functioning, peer relationships, and both overt and relationalaggression in children and adolescents,37 was assessed atmultiple time points.Assessments of Early Life Experiences and Risk FactorsMaternal Support. Maternal support was measured atassessment 2 (ages 4.0–7.11 years) through observational coding of the waiting task, a laboratory taskdesigned to produce mild stress for both members ofthe parent–child dyad. The task requires the child towait 8 minutes before opening a wrapped gift while theparent completes questionnaires. The parent’s supportivecaregiving strategies (providing guidance, verbal assists,warmth and affection, emotion coaching, changingproximity, incorporating the child in their work, andclear directions and explanations) were coded by stafftrained to reliability. Support score was calculated asthe number of supportive events per minute (unpublished data, January, 2006.)Adverse Childhood Experiences. We created an ACEsvariable based on items identified by Felitti et al.,38 summing items assessing parent-reported poverty, parental suicide attempts, substance abuse, and psychopathology andparent- or child-reported traumatic events, then convertingto a z score, as detailed elsewhere.39 ACEs variables includeda variable comprising experiences only during the preschoolperiod (3–6 years), one comprising experiences only in theschool-age period (7–9 years), and one comprising lifetimeexperiences from all assessments in which these werecaptured (assessments 1–8). See Table S3, available online,for the rates of ACEs during each developmental period. Toensure the robustness of results, 2 alternative z-transformedACEs variables were created, one excluding parental psychopathology and one excluding a history of poverty, owingto the inclusion of these factors as independent predictors inour analyses.Assessments of Maternal Psychopathology. MaternalBPD symptoms were measured using the borderline subscale of the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI-BOR), awidely used self-report measure of borderline pathologywith high criterion validity,40 during assessment 9. Generalmaternal psychopathology was assessed using the FamilyInterview for Genetic Studies41 and questions about currenttreatment; mothers comprised 92% of informants. Maternalhistory of psychopathology (any affective, psychotic, oranxiety disorder or ADHD) and maternal history ofdepression were calculated as dichotomous variables. Theywere assessed at assessment 7, when participants were 9.17–14.89 years of age and were assumed to be lifetime riskfactors for the child.Early Life Psychopathology. Symptoms of MDD, GAD,SAD, SOC, ADHD, ODD, and CD were assessedfrom the first to the eighth assessments using thesemistructured parent-report interview Preschool AgePsychiatric Assessment (PAPA)42 from ages 3 to 7 yearsand the parent- and child-report Child and AdolescentPsychiatric Assessment (CAPA)43 from age 8 and older.MDD, anxiety disorders (GAD/SAD/SOC), ADHD,and ODD/CD symptom scores were sums of the totalnumber of DSM-IV diagnostic symptoms endorsed byeither the caregiver or the child during each assessment.These psychopathology variables were collapsed intointernalizing (sum of MDD and anxiety disorder(GAD/SAD/SOC) symptoms) and externalizing (sum ofADHD, ODD, and CD symptoms) composites. Preschool composites were averages of all assessmentscompleted between ages 3 and 5.11 years; school-agecomposites were averages of all assessments completedbetween ages 6 and 9.11 years.Assessments of Peer Relationships. Peer relationshipswere assessed with the parent-reported HBQ,37 collected ateach assessment. The global peer relationships scale assessedthe participants’ relationships with peers during the preschool (ages 3–5.11 years) and school-age (ages 6–9.11years) periods. The composite assesses the quality of achild’s friendships, the extent to which the child is liked bypeers, and how frequently the child is teased. The HBQbullied by peers and relational victimization subscales wereused in planned post hoc analyses.Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent PsychiatryVolume - / Number - / - 2021FLA 5.6.0 DTD JAAC3166 proof 7 January 2021 6:50 pm 38339340341342343344345346347348349350351352

GESELOWITZ et 402403404405406407408409410411Q7Suicidality and Self-Injury Composite Variables. SuicidalityRESULTScomposite variables were derived from the PAPA/CAPAduring the preschool and school-age periods and fromthe K-SADS-PL at assessment 9. Each compositesummed items measuring recurrent thoughts of death,suicidal ideation, and nonsuicidal self-injury. Thepreschool/school-age composites from the PAPA/CAPAalso included items measuring death and suicide themesin play; the K-SADS-PL composite included itemsmeasuring suicidal intention and attempts, similar toWhalen et al.31 Of the 306 children in the PDSsample, 56 (18%) had suicidality/self-injury during thepreschool period.BPD Is Prevalent in SamplePlan of AnalysesRegressions. Regression analyses were run to evaluate theassociation between adolescent BPFS-C score and concurrent functional impairment, with follow-up multipleregression analyses controlling for significant predictors(gender, preschool ACEs, and concurrent MDD) and aseparate regression controlling for other psychiatric diagnoses (MDD, anxiety disorders, ADHD, ODD, and CD)(Table 2).Bivariate and multiple regression analyses controllingfor gender and preschool ACEs were run to evaluate theassociation between early life risk factors with adolescentBPFS-C score. To assess if predictors of dimensionalborderline symptoms also predicted likely BPD diagnosis(BPFS-C score 65), we ran logistic regressions, againcontrolling for gender and preschool ACEs.As above, we calculated ACEs variables excludingparental psychopathology and excluding poverty and performed regressions predicting BPD symptoms from thesevariables. A separate linear regression predicted BPFS-Cscore excluding the small subset of participants that experienced sexual abuse. We tested whether preschool ACEsdifferentially predicted the 4 BPFS-C subscales with planned regressions of each subscale. Post hoc analysis of theassociation between preschool ACEs and depression symptoms from age to 14 to 19 evaluated the specificity of therelationship between ACEs and BPFS-C score. We testedwhether there was a significant difference in the varianceattributable to ACEs in BPD as opposed to MDD symptoms using the Steiger’s z-test.Correction for Multiple ComparisonsQ8All p values were corrected for multiple comparisons, usingthe Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.44 All p values reportedin Results are the false discovery rate (FDR)–corrected pvalues and are denoted as FDR-corrected p.4www.jaacap.orgPresumptive BPD at age 14–19 years was prevalent in thissample enriched for preschool depression. Of the 170 participants in our sample, 41 (24.1%) scored 65 on theBPFS-C, exceeding the suggested cutoff for BPD on theBPFS-C (Table 1).BPD Is Associated With Concurrent PsychopathologyLikely diagnosis of BPD, as indicated by BPFS-C score 65, was positively associated with all concurrent psychiatric diagnoses examined. Suprathreshold BPD symptomswere associated with increased risk of concurrent depression(odds ratio [OR] 15.87, 95% CI 5.32–47.31), anxietydisorders (OR 15.87, 95% CI 1.71–27.58), ADHD (OR3.64, 95% CI 1.27–10.43), and ODD/CD (OR 15.39,95% CI 3.12–75.95). However, while participants withsuprathreshold BPD symptoms had extensive comorbidity,no comorbid diagnosis was present in more than half ofparticipants with presumptive BPD. Of participants withBPFS-C score 65, 16 (39%) met criteria for MDD, 20(49%) met criteria for an anxiety disorder, 8 (20%) metcriteria for ADHD, and 8 (20%) met criteria forODD/CD.Borderline Personality Symptoms Are Associated WithClinical ImpairmentBivariate analyses showed BPFS-C score was significantlyassociated with each measure of functional impairment(Table 2). Specifically, higher BPFS-C scores were associated with decreased global functioning assessed by CGASparent (b ¼ .37, FDR-corrected p .001) and child(b ¼ .52, FDR-corrected p .001) interview andincreased functional impairment assessed by HBQ (b ¼.30, FDR-corrected p .001). In the domain of peer relationships, higher BPFS-C scores corresponded to worseglobal peer relationships (b ¼ .19, FDR-corrected p ¼.0124), increased relational aggression (b ¼ .31, FDRcorrected p .001), and increased overt aggression (b ¼.30, FDR-corrected p .001) assessed by HBQ. HigherBPFS-C scores also corresponded to lower academic functioning as assessed by HBQ (b ¼ .27, FDR-corrected p .001) and increased suicidality/self-injury composite score(b ¼ .31, FDR-corrected p .001).In the multivariate models controlling for preschoolACEs, gender, and concurrent MDD (Table 2), all of whichwere shown to be associated with increased BPFS-C scoresin regression analyses, BPFS-C scores were significantlyassociated with decreased global functioning as assessed byCGAS child interview (b ¼ .36, FDR-corrected p Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent PsychiatryVolume - / Number - / - 2021FLA 5.6.0 DTD JAAC3166 proof 7 January 2021 6:50 pm 61462463464465466467468469470

PRESCHOOL PREDICTORS OF ADOLESCENT BPDTABLE 1 Rates of Psychiatric Conditions Comorbid With Suprathreshold Borderline Personality Disorder h BPD(n ¼ .5n162088Participantswithout BPD(n ¼ 129)%3.920.96.31.6n52782Q12Participants with vs. without BPDc224.6111.355.7811.27p .0001.0008.0162.0008FDR p .0001.0011.0162.0011OR15.873.603.6415.3995% CI(5.32, 47.31)(1.71, 7.58)(1.27, 10.43)(3.12, 75.95)Note: ADHD ¼ attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BPD ¼ borderline personality disorder; CD ¼ conduct disorder; FDR p ¼ false discovery rate–corrected p; GAD ¼ generalized anxiety disorder; MDD ¼ major depressive disorder; ODD ¼ oppositional defiant disorder; OR ¼ odds ratio; SAD ¼separation anxiety disorder; SOC ¼ social phobia.001), increased relational aggression (b ¼ .22, FDRcorrected p ¼ .048), and increased overt aggression (b ¼.29, FDR-corrected p ¼ .010). In the multivariate modelscontrolling for gender and comorbid diagnoses, includingever having a diagnosis of MDD, anxiety disorder (GAD,SOC, PTSD), ADHD, ODD, and CD, BPFS-C scoreswere significantly associated with decreased global functioning as assessed by CGAS parent (b ¼ .23, FDRcorrected p ¼ .014) and child (b ¼ .41, FDR-correctedp ¼ .008) interview, poorer academic functioning(b ¼ .16, FDR-corrected p ¼ .037), increased relationalaggression (b ¼ .25, FDR-corrected p ¼ .014), overtaggression (b ¼ .26, FDR-corrected p ¼ .012), and suicidality and self-injury (b ¼ .19, FDR-corrected p ¼ .045).Preschool and School-Age Adversity, MaternalPsychopathology, and Problematic Peer RelationshipsPredict BPD Symptoms and DiagnosisQ9Outside the domain of peer relationships, each childhoodvariable examined was significantly associated with BPDsymptoms (Table 3) (correlations between variables areshown in Table S4, available online). Bivariate analysesdemonstrated that BPFS-C scores were associated with female gender (t ¼ 2.44, FDR-corrected p ¼ .024), lower IQ(b ¼ .15, FDR-corrected p ¼ .027), and lower familyincome-to-need ratio during preschool (b ¼ .21, FDRcorrected p ¼ .024). Preschool (b ¼ .38, FDR-correctedp .001) and school-age (b ¼ .29, FDR-corrected p .001) ACEs predicted increased BPFS-C score, as did lowerpreschool maternal support (b ¼ .20, FDR-corrected p ¼.027), maternal borderline features (b ¼ .26, FDR-correctedp ¼ .001), maternal depression history (b ¼ .19, FDRcorrected p ¼ .021), and maternal history of any psychopathology (b ¼ .25, FDR-corrected p ¼ .002). However,preschool and school-age peer relationships were not significantly associated with BPFS-C score when accounting formultiple comparisons. Planned post hoc analyses found thatchildhood bullying victimization and relational victimizationwere also not significantly associated with BPFS-C score.When controlling for gender and preschool ACEs, lowpreschool maternal support continued to predict increasedBPFS-C scores (b ¼ .20, FDR-corrected p ¼ .024).However, IQ, preschool income-to-needs ratio, school-ageACEs, maternal BPD symptoms, maternal depression history, and maternal psychopathology history no longersignificantly predicted BPFS-C scores.In assessing whether predictors of BPD symptoms alsopredicted presumptive BPD diagnoses (BPFS-C score 65),we found that female gender, lower IQ, low baselineincome-to-needs ratio, and higher preschool and school-ageACEs all were predictive of presumptive BPD. However, ina stepwise multiple logistic regression, preschool ACEs werethe only significant predictor of presumptive BPD diagnosiswhen all were included in the model.Preschool ACEs Are a Robust Predictor of BPDSymptomsWhen calculated without parental psychopathology (b ¼.31, p .001) and poverty (b ¼ .37, p .001) as potentialACEs, preschool ACEs continued to predict BPFS-C scores.When recalculated excluding children who experiencedsexual abuse, which was done given prior reports of specificassociations between sexual abuse and BPD, preschoolACEs also continued to predict BPFS-C scores (preschoolACEs b ¼ .36, p .001), though adolescents with a lifetime history of sexual abuse had significantly higher BPDsymptoms (mean [SD] 69.43 [11.574]) than adolescentswho had not experienced sexual abuse (mean [SD] 55.01Q 10[13.055]; t ¼ 3.987, p .001).Post hoc analysis to determine whether preschool ACEs Q 11predicted significantly more variance in any specific BPFS-Csubscale than others demonstrated that the varianceJournal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent PsychiatryVolume - / Number - / - 2021FLA 5.6.0 DTD JAAC3166 proof 7 January 2021 6:50 pm 74575576577578579580581582583584585586587588

www.jaacap.orgNote: When controlling for correlated factors (gender, preschool adverse childhood experiences, and concurrent diagnosis of MDD), borderline personality disorder symptoms continue topredict global functioning and aggression. When controlling for comorbid psychopathology, borderline personality disorder symptoms continue to predict global and academic functioningas well as aggression. Boldface indicates significant results. ACEs-z ¼ z-transformed adverse childhood experiences; ADHD ¼ attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CD ¼ conduct disorder; CGAS ¼ Child Global Assessment Scale; FDR p ¼ false discovery rate–corrected p; HBQ ¼ Health and Behavior Questionnaire; MDD ¼ major depressive disorder; ODD ¼oppositional defiant disorder; Stand. Est. ¼ standardized estimate.n Stand. Est.tpFDR p135L0.231L2.812 .006.014135L.407L5.44 .001 .0081350.2322.609.119.159135L0.148L1.568 .183.182156L0.158L2.302 1350.192.14.034.045tpFDR pL2.21 .029.057L4.64 .001 .0011.98.049.074L1.34 .183.183L1.93 .055.0742.40.018.0783.08.003.0101.45.150.171p .001 .001 .001.012 .001 .001 .001 .001tL5.16L7.854.12L2.53L3.684.204.104.70n Stand. 1680.301700.34Measure of adolescentfunctioningParent CGASChild CGASHBQ functional impairmentHBQ global peer relationshipsHBQ academic functioningHBQ relational aggressionHBQ overt aggressionChild-reported suicidality andself-injuryBivariate modelFDR p .001 .001 .001.012 .001 .001 .001 .001n Stand. 1350.291370.11Model with covariates: gender,diagnosis MDD, anxiety disorder,ADHD, CD, ODD6Model with covariates: gender,preschool ACEs-z, concurrent MDDdiagnosisTABLE 2 Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms Predict Impairment Across a Range of 6637638639640641642643644645646647Q14Q13GESELOWITZ et al.explained for each subscale was statistically equivalent: selfharm (adjusted R2 ¼ .097, F ¼ 15.669, p .001), relationships (adjusted R2 ¼ .143, F ¼ 23.668, p .001),identity problems (adjusted R2 ¼ .125, F ¼ 20.396, p .001), affect instability (adjusted R2 ¼ .042, F ¼ 7.010, p ¼.009), all Steiger’s z 1.5 and ps .10.Preschool ACEs predicted BPD symptoms above andbeyond broad internalizing or externalizing symptoms.When predicting later BPD symptoms, the relationshipbetween preschool ACEs remained significant (b ¼ .23, p ¼.006) when gender, concurrent internalizing symptoms, andconcurrent externalizing symptoms were entered into themodel, though concurrent externalizing symptoms also wererelated to BPD symptoms (b ¼ .34, p .001). Whilepreschool ACEs are also known to predict adolescentdepression, the relationship between preschool ACEs andadolescent BPD symptoms was numerically stronger thanthe relationship between preschool ACEs and adolescentdepression, though the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 1). A post hoc bivariate analysis found thatpreschool ACEs predicted 14.9% of the variance in BPFS-Cscore (b ¼ .38, p .001, R2 ¼ .149) versus only 4.1% ofthe variance in MDD symptoms, despite being a significantpredictor (b ¼ .202, p ¼ .018, R2 ¼ .041). However, therewas no significant difference in the variance explained usingSteiger’s z (z ¼ 1.618, p ¼ .10).Preschool and School-Age Psychopathology PredictBPD Symptoms and DiagnosisIn bivariate analyses, both childhood internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms were associated withincreased adolescent BPD symptoms. Preschool and schoolage internalizing symptoms (preschool: b ¼ .28, FDRcorrected p ¼ .001; school age: b ¼ .17, FDR-correctedp ¼ .033) and externalizin

NEW RESEARCH Preschool Age Predictors of Adolescent Borderline Q1Q2Personality Symptoms Q3 Ben Geselowitz, BA, Diana J. Whalen, PhD, Rebecca Tillman, MS, Deanna M. Barch, PhD, Q18 Joan L. Luby, MD, Alecia Vogel, MD, PhD Objective: Developmental models of borderline personality disorder