Transcription

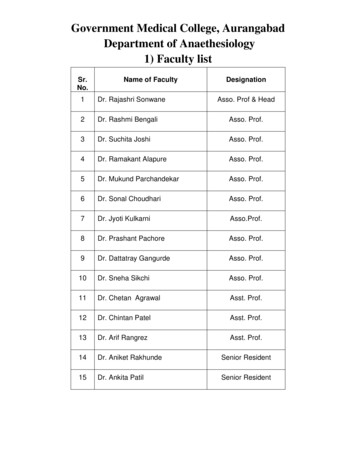

JMSCR Vol 05 Issue 12 Page 32023-32033 December2017www.jmscr.igmpublication.orgImpact Factor 5.84Index Copernicus Value: 71.58ISSN (e)-2347-176x ISSN (p) 2455-0450DOI: l ArticleMental Morbidity among Medical Students in IndiaAuthors11Ram Pratap Beniwal , Madan Mohan Bhojak2, S.S.Nathawat3, Kiran Jakhar4MD (Psychiatry), Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Centre of Excellence in Mental Health,PGIMER-Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital, New Delhi, IndiaEmail: beniwal 9@yahoo.co.in2MD (Psychiatry), Retired Professor. Department of Psychiatry, S.M.S. Medical College, Jaipur, IndiaEmail: bhojakmm@yahoo.com3Ph. D, Professor (Clinical Psychology). Amity Institute of Behavioural and Allied Sciences, Jaipur, IndiaEmail: ssnathawat@gmail.com4MD, DNB (Psychiatry) Pool Officer (Senior Research Associate). Department of Psychiatry, All IndiaInstitute of Medical Sciences, New DelhiName and address of the department or institution to which the work should be attributedDepartment of psychiatry, S.M.S Medical College, Jaipur, RajasthanCorresponding AuthorKiran JakharAddress: Room No. 4096, Department of Psychiatry,All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi – 110029Phone numbers: 8860997164, Email: kjakhar48@gmail.comAbstractAims: The current study compares the rate and pattern of mental morbidity in medical students of first semester andfinal semester and to evaluate its association with socio-demographic and other variables.Methods and Material: This was cross-sectional study done at tertiary care centre of North India. Sample includedfirst and final semester students. Socio-demographic information sheet and GHQ-60 questionnaire wasadministered, based on which probable cases (score of 12 or above) of psychiatric problems were detected whichwere then diagnosed according to ICD-10. A battery of instruments to determine the role of various factorsincluding personality disorders, neurosis, life events, family and college environment were administered. Frequencydistribution, chi-square test and‘t’test were applied.Results: Medical college entrants had higher psychiatric problems than their outgoing counterparts (32% V/s 25%)with higher male preponderance. Low and middle family income outgoing medical students had significantly higherfrequency of mental ill health (p 0.05). Mentally unwell entrants had significant difference on all the parameters ofMHQ as compared to outgoing students who were positive on only four parameters. Medical entrants had moredysfunctional personality traits, less coping responses as compared to outgoing students. In medical outgoing group,significant differences were observed on both presumptive stressful life events and medical college environmentscale while significant differences exist only on medical college environment scale in entrant group.Conclusions: Compared to medical outgoing students, entrant had more psychiatric problems with largerdisturbances on MHQ, dysfunctional personality traits, less coping response, difficult medical college environment.Keywords: Medical students, coping response, environment, life events.Ram Pratap Beniwal et al JMSCR Volume 05 Issue 12 December 2017Page 32023

JMSCR Vol 05 Issue 12 Page 32023-32033 DecemberIntroductionMedical schools offer an extremely challengingacademic experience and are responsible fordelivering a highly systematic curriculum to thestudents [1]. They are responsible for ensuring thatthe graduates turn out to be highly knowledgeable,skillful and professional candidates [2]. In order toachieve these goals, they offer a curriculum ofdidactic lectures, modeling, supervised practice,mentoring and hands-on experience to augmentindividual study[3]. Although medical studentsbegin with better mental health indictors than agesimilar college graduates in the general population[4]. Unfortunately, some aspects of the trainingprocess have unintended negative consequenceson students’ personal health [3]. Along with highworkload, examination stress and performancepressure, there are stressors in the individual’spersonal life, which also adds to the situation [5,6].So medical training can be extremely stressful andthat high stress is a risk factor for a wide range ofpsychological and health related consequences [7].It is well-documented that medical studentsexperience high levels of stress and psychologicalmorbidity compared to age matched peer students[8,9, 6,10]Mild depression among medical studentsranges from 25% to 60%, and moderate to severedepression affects approximately 13% to 14% ofmedical students [11,12]. Psychological distress canmanifest in a variety of ways including burnout,depression, stress, low mental quality of life(QOL), low physical QOL, and fatigue [13,9,14,10].Physical health related issues like headaches,gastrointestinal disorders and self-medication withdrugs and alcohol may occur [15] but also lead totragic consequence of suicide [10].For an individual medical school trainee, it maylead to psychological morbidity (anxiety ordepression), loss of objectivity, an increasedincidence of errors and even improper behaviour,such as cheating in examinations, fraud ornegligence[5,6]. Studies suggest that medicalstudents, who experience a high incidence ofpersonal distress[16] have potential adverseconsequences on academic performance[17],2017competency[18], professionalism[19], and health [20].Stress in medical students has been linked toacademic dishonesty [21] and decreased empathy[22]. Furthermore, it is recognized that doctors intraining and in practice who fail to manage theirstress levels are less likely to be safe or competenthealth care providers [23]. Untreated depressionpresents a public health concern not just fortrainees, but for the general population as it hasbeen associated with increased burnout, poorquality patient care, and a decline in the physicianworkforce [24].Physician self-care is an important foundation forquality patient interactions and outcomes [25].Student physicians’ distress and burnout maypredict adverse future health status and practiceperformance [26]. So, it is critical for medicaleducators to understand the prevalence and causesof factors that can positively and negativelyinfluence student health [3].In order to address this issue, current study wasundertaken to evaluate the rate and pattern ofmental morbidity in medical students of firstsemester and final semester and to compare onvarious measures of neurosis. It also aimed to findthe association of socio-demographic variables,role of personality disorder, coping strategies inthese students, to understand the significance offamily and college environment the contributionof life events in the development of these disorder.Materials and MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study which wasconducted at tertiary care centre in North India.The sample included all the students of first andfinal semester, who gave written informed consentfor the participation of the study.Instruments Used1.Socio-demographic information sheet: Itconsist of socio-demographic profile & detailscontaining information regarding – Age, gender,religion, occupation, monthly income, maritalstatus, education, family type, family education,birth order, domicile, language and residentiallocation (hostler or day scholar) etc.Ram Pratap Beniwal et al JMSCR Volume 05 Issue 12 December 2017Page 32024

JMSCR Vol 05 Issue 12 Page 32023-32033 December2. Goldberg’s General Health Questionnaire,(GHQ-60) Hindi Version (Gautam & Nijhawan,1982)[27].David P. Goldberg – GHQ, 60 item version is aself-administered questionnaire. The respondent isasked to compare his recent state with his usualstate. Minimum score is 0 and maximum is 60.The optimum threshold for case detection in ageneral practice setting was found to be a score of12 or above with sensitivity of 95.4% andspecificity of 87.7%. It assists generalpractitioners and physicians in the identificationof the patients with minor psychiatric illness and itwould serve epidemiologists acting as a screeningdevice. It can detect affective neurosis,neurasthenia or even psychotic episodes ororganic psychosis, when accompanied by anxietyor affective symptoms.3. Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire (MHQ)(Crown & Crisp, 1966). Hindi version (Bhat &Srivastava, 1974) [28]. It is a 48-item short clinicaldiagnostic self-rating scale for psychoneuroticpatients consisting of six subscales. It allows rapidqualification of common symptoms and traitsrelevant to the conventional categories of neuroticillness to provide a rapid approximation to whatwould be expected from a diagnostic – psychiatricinterview. It also provides total quantitative scoreon neurosis. Hindi version of MHQ was applied togroups of normal population (homogenous andheterogenous) and a neurotic population andfound it to be very sensitive, reliable and validinstrument for differentiating the neurotics fromthe normal.4. ICD-10 International Personality DisorderExamination for WHO[29]. The ICD-10International Personality Disorder Examination(IPDE) was employed to assess personalitydisorders. This scale was readily available (editedby Loranger, Janca, & Sartorius, in 1997 forW.H.O.). Initially scale was developed takingseveral items. Later on these items were reducedto only 59 items. It includes Paranoid, schizoid,2017dissocial, impulsive, borderline, histrionic,anakastic, anxious and dependent personalitydisorder.5. Coping Response Inventory [Moos, 1992] [30].CRI was developed by Dr. Rudolf Moos, atStanford University, California (in the year 1988,revised in 1992). The coping responses inventoryis composed of eight subscales that measuredifferent types of coping responses to stressful lifecircumstances. The first four subscales measure‘approach coping’ (Logical Analysis, PositiveReappraisal, Guidance/Support and ProblemSolving), the second set of four subscales measure‘avoidance coping’ (Cognitive Avoidance,Resigned Acceptance, Seeking Rewards andEmotional Discharge). The first two subscales ineach set reflect ‘cognitive coping strategies’, thethird and fourth subscales in each set reflect‘behavioural coping strategies’.6. Family Environment Scale [Moos, 1974]Revised and Hindi Version (Joshi, 1984) [31]. Thefamily environment scale suitable for Indiancultural norms as developed by Dr. M.C. Joshiand O.R. Vyas was used. This scale has beendeveloped to provide a handy tool to know familyenvironment of the subject. The familyenvironment scale (FES) assesses the socialclimates of all types of families. It focuses on themeasurement and description among familymembers, on the directions of personal growthwhich are emphasized in the family, and on thebasis organizational structure of the family. Itinvolves three dimensions- Relationship Dimension (cohesion, expressiveness and conflict),Personal growth dimension (Independence,Achievement orientation, Intellectual culturalorientation, Active recreational orientation andMoral religious emphasis) and SystemMaintenance Dimensions (Organization andcontrol). The scale consists of 90 Items and thereare 9 items in each subscale. The item of eachsub-scale are scattered in the scale. Each item isscored on a two-point scale where the score of “0”Ram Pratap Beniwal et al JMSCR Volume 05 Issue 12 December 2017Page 32025

JMSCR Vol 05 Issue 12 Page 32023-32033 December(Zero) represent the category of “no” and thescore of “1” (one) represent the category of “yes”.There is no aggregate score for the scale; all thesub-scales are scored separately. Some of all theitems in each sub-scale represent them.7. Medical College Environment Scale.Standardized interview schedule for collegeenvironment scale was prepared in the form of tenstatements, covering major aspects of medicalcollege environment. The statements are requiredto be replied in three categories: Yes, cannot sayand No. The scoring was done in the form ofthree-point rating scales as 2, 1, and 0 dependingon nature and direction of facilitation ordisturbance of medical college environment asperceived by the respondents.8. Presumptive Stressful Life Events Scale(PSLES) by Gurmeet Singh et al., 1984[32]. It ismodified version of the Social ReadjustmentRating Questionnaires (SRRQ) of Holmes andRahe (1967). Hundred was kept as the higheststress score and zero as no perceived stress. Scaleitems were classified into (a) desirable,undesirable or ambiguous and (b) personal orimpersonal. Scoring of stressful life events wasdone as follows. If a subject perceived onestressful life event in preceding one year, a scoreof 1 was given, if a subject perceived 2 stressfullife events in the same period a score of 2 wasgiven & likewise. Any particular event thathappened twice or more in the preceding year wastaken to happen on and a score of (1) was givenfor that particular event.Assessment procedureApproval from Institutional Ethical Committeewas taken at the outset of the study. All thestudents of first and final semester who werewilling to participate in the study and agreed togive written informed consent were recruited. Atthe start of the study, the participants wereinformed briefly about the purpose of the study.2017Study was conducted in two phases. In first phase,socio-demographic information sheet and GHQ60 questionnaire was administered to all theparticipants of first and final semester. On thebasis of the questionnaire probable cases (whoscored 12 or above on GHQ-60) of psychiatricproblems were detected. Thereafter these probablecases were interviewed to ascertain “PsychiatricCasenessness” in these screened participants.Diagnosis was made in consultation with aqualified psychiatrist according to the ICD-10.False positive cases were dropped.In second phase, the diagnosed participants d a battery of instruments to determinethe role of various factors including personalitydisorders, neurosis, life events, family and collegeenvironment. Scores obtained on differentmeasures were arranged and entered in excel sheetand data was analyzed.Frequency distribution in terms of mean andstandard deviation, proportions and percentagewas carried for socio-demographic and clinicaldetails. Statistical procedure used included chisquare test and‘t’ test (Statistical analysis forcomparing means of two groups (with smallsamples – either or both 30).ResultsGHQ scores of 12 and above were more inmedical college entrants than outgoing students,which depicts that there was higher prevalence ofpsychiatric problems in medical college entrantsthan their outgoing counterparts (32% V/s 25%).The above table also reveals that male studentsboth in medical entrants as well as in outgoinggroup outnumbered their female counterparts inthe rate of psychiatric problems (33.33% &26.13% Vs 26.66% & 21.42%).Medical entrants of low, middle and higherincome groups were more or less evenlydistributed in terms of their mental health and illhealth. Thus, family income did not influenceprevalence of psychiatric problems in medicalentrants. However low and middle family incomeRam Pratap Beniwal et al JMSCR Volume 05 Issue 12 December 2017Page 32026

JMSCR Vol 05 Issue 12 Page 32023-32033 Decemberoutgoing medical students had significantly higherfrequency of mental ill health (36% & 37%respectively) as compared to their counterpartswho had higher family income (10%).In the medical entrant group, percentage ofmentally healthy hostler was more as compared totheir day-scholar counterparts (35% v/s11%).Hostler and day-scholar were more or less evenlydistributed in terms of their mental health and illhealth in outgoing group. Thus, residence did notinfluence prevalence of psychiatric problems inmedical outgoing students (Table 1).Significant difference were seen on all these sevenmeasures of MHQ, suggesting that mentallyunwell medical entrants had significantly morefree-floating anxiety, obsessional neurosis, phobicanxiety, somatic anxiety, depression, hystericalneurosis and total neurotic score as compared tomentally healthy ones. While mentally unwellmedical outgoing students showed significantdifferences on only four of the seven measures,including free floating anxiety, somatic anxiety,depression and total neurotic score as compared totheir mentally healthy counter parts.Significant differences were observed on seven ofthe nine measures of IPDE, suggesting thatmentally unwell medical entrants havesignificantly more paranoid, schizoid, dissocial,borderline, anankastic, anxious and dependencepersonality traits as compared to mentally well. Itwas observed that mentally unwell outgoingmedical students had more borderline and anxiouspersonality traits as compared to mentally well assignificant difference was observed only on twomeasures (borderline and anxious personalitytraits) (Table 2).Out of the eight measures of CRI, significantdifferences were found only a single measure ofseeking support or guidance. It suggests thathealthy medical entrants make more efforts toseek support and guidance in crisis as compared tothe ones who are mentally unhealthy. Whilesignificant differences were observed on three ofthe eight measures in mentally well medicaloutgoing students suggesting that mentally healthy2017medical outgoing student having more problemsolving and seeking reward as their copingmechanism as compared to mentally unwell onesbut at the same time they have significantly lessresigned acceptance in comparison to mentallyunwell as coping response to stressful lifecircumstances (Table 3).There was no significant difference on anymeasure of family environment scale in mentallywell and unwell medical entrants. Althoughsignificant differences were observed on twomeasures in medical outgoing group. Thus,mentally unwell medical outgoing students hadmore achievement - Orientation and less moralreligious emphasis in their family environment ascompared to mentally healthy ones.Presumptive stressful life event scale had nosignificant difference in medical entrant groupwhile medical college environment scalesuggested that mentally unwell medical entrantshad more difficulties in adjusting as compared tomentally well. While in medical outgoing group,significant difference was observed on bothpresumptive stressful life events and medicalcollege environment scale suggesting thatmentally unwell outgoing students had significantmore stressful life events and more unlikelycollege environment then their mentally healthycounter parts (Table 4).Ram Pratap Beniwal et al JMSCR Volume 05 Issue 12 December 2017Page 32027

JMSCR Vol 05 Issue 12 Page 32023-32033 December2017Table 1. Socio-demographic composition and clinical variables of mentally well and unwell participants inMedical college entrants and outgoing students.GroupsGHQICD-10Family typeFamily incomeDomicileFamily rbanBoth educatedFather educatedBoth uneducatedHindiEnglishHostlerDay scholarMedical College Entrants (n 141)Mentally wellMentallyTotalunwell ( 12)684352(36.8%)2197437 (33.33)45(31.9%)228 (26.66)49 (73%)18 (27%)6747 (64%)27 (36%)7446 (71%)19 (29%)6518 (60%)12 (40%)3032 (70%)14 (30%)4643 (66%)21 (33%)6453 (69%)24 (31%)7745 (66%)23 (34%)6839 (72%)15 (285)5412 (63%)7 (63%)1969 (69%)31 (31%)10027 (66%)14 (34%)4180 (65%)43 (35%)12316 (89%)2 (11%)18Outgoing Medical Students (n 116)Mentally wellMentally unwellTotal6121652220 (77%)67 (74%)16 (64%)26 (63%)45 (90%)19 (70%)68 (76%)61 (75%)23 (79%)3 (50%)49 (75%)38 (75%)64 (73%)23 (82%)27723 (26.1%)6 (21.4%)6 (23%)23 (26%)9 (36%)15 (37%)5 (10%)8 (30%)21 (24%)20 (25%)6 (21%)3 (50%)16 (25%)13 (25%)24 (27%)5 (18%)34(29.3%)29 (25%)269025415027898129665518828Table 2 Mean and SDs of mentally well and unwell medical entrants and outgoing students on differentmeasures of MHQ (Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire) and IPDESubscaleMedical entrantsOutgoing medical studentsMentally well (n 30)Mentally unwellt valueMentally well (n 30)Mentally unwellt value(Mean SD)(n 45) (Mean SD)(Mean SD)(n 29) (Mean SD)Middlesex Hospital QuestionnaireFFA3.30 ( 2.03)7.85( 3.05)7.15***3.80( 2.45)7.03( 2.20)5.35***OBS6.23( 1.7)7.51( 2.35)2.15*7.06( 2.18)7.41( 2.76)0.54PHO4.06 ( 2.5)5.62( 3.27)2.21*4.06( 2.48)4.51( 2.40)0.71SOM3.13( 2.4)6.58( 3.15)5.10***2.00( 1.53)3.96( 1.86)4.44***DEP3.40( 1.7)6.46( 3.20)4.78***2.60( 1.70)5.62( 2.70)5.16***HYS2.26( 2.3)4.33( 2.49)4.10***2.06( 1.80)3.00( 2.20)1.78Total Neurotic Score22.4( 8.2)38.33( 12.90)5.99***21.60( 8.5)31.62( 9.0)4.39***IPDEParanoid2.00( 1.2)3.00( 1.22)3.49***2.47( 0.97)2.31( 1.45)-0.49Schizoid3.63( 1.4)4.50( 1.61)2.38*3.73( 1.08)3.38( 1.52)-1.03Dissocial0.80 ( 0.88)1.47( 1.14)2.70**0.86( 1.10)1.10( 0.8600.92Impulsive1.36( 1.2)1.82( 1.38)1.451.33( 1.09)1.65( 1.37)1.00Borderline1.40( 0.7)2.20( 1.013.73***1.26( 0.69)2.03( 0.98)3.48***Histrionic2.20( 1.3)2.58( 1.49)1.132.40( 1.16)2.58( 1.45)0.54Anankastic2.43( 1.3)3.85( 1.35)4.57***2.66( 1.64)3.38( 1.70)1.64Anxious1.56( 1.0)3.20( 1.42)5.39***1.46( 1.16)2.45( 1.32)3.02**Dependence2.30( 1.5)3.15( 1.52)2.45*2.00( 1.23)2.55( 1.50)1.55* P 0.05, ** P 0.01, *** P 0.001FFA-Free-Floating Anxiety, OBS- Obsessional traits and symptoms, PHO- Phobic Anxiety, SOM-Somatic concomitants of anxiety, DEP- Neurotic Depression,HYS- Hysterical personality traits.Table 3 Mean and SDs of mentally well and unwell medical Entrants and outgoing medical students ondifferent measures of Coping Response Inventories (CRI)SubscaleMedical entrantsOutgoing medical studentsMentally well(n 30)Mentally unwell(n 45)t-valueMentally well(n 30)Mentally unwell(n 29)(Mean SD)(Mean SD)(Mean SD)(Mean SD)L.A.11.66( 3.95)10.40( 3.15)-1.539.80( 3.93)9.20( 2.57)P.R.13.63( 3.55)12.87( 3.47)-0.9313.40( 2.96)13.06( 2.65)S.G.14.00( 3.44)12.33( 3.37)-2.08*12.80( 4.23)12.00( 3.67)P.S.13.73( 3.62)13.13( 3.35)-0.7315.13( 2.75)13.34( 3.14)C.A.7.93( 3.49)8.06( 3.28)0.177.06( 3.37)8.13( 3.62)A.R.5.66( 3.67)7.13( 3.60)1.714.60( 3.46)7.13( 3.24)S.R.12.73( 3.24)11.17( 3.42)-1.9713.40( 2.62)11.13( 2.85)E.D.5.90( 3.02)6.82( 3.24)1.244.53( 2.19)4.80( 2.21)* P 0.05, ** P 0.01LA-Logical Analysis, PR-Positive Reappraisal, SG-Guidance/Support, PS- Problem Solving, CA-Cognitive Avoidance, AR-Resigned Acceptance,Reward, ED-Emotional DischargeRam Pratap Beniwal et al JMSCR Volume 05 Issue 12 December .45SR-SeekingPage 32028

JMSCR Vol 05 Issue 12 Page 32023-32033 December2017Table 4 Mean and SDs of mentally well and unwell medical entrants and outgoing medical students ondifferent measures of Family Environment Scale (FES), Presumptive Stressful Life Events (PSLE) andMedical College Environment Scale (MCES)SubscaleMedical entrantsOutgoing medical studentsMentally healthyMentally unhealthyt-valueMentally healthyMentally unhealthyt-value(n 30) (Mean SD(n 30) (Mean SD(n 30) (Mean SD(n 30) (Mean SDCOH8.36( 0.89)8.15( 0.79)-1.078.33( 0.802)8.00( 1.44)-1.10EXP6.06( 1.31)5.77( 1.39)-0.905.80( 1.49)5.48( 1.52)-.81CONF2.50( 1.07)2.78( 1.28)0.982.60( 1.22)2.69( 1.44)0.26IND6.90( 1.54)7.22( 1.36)0.957.40( 1.16)6.89( 1.31)-1.56AO5.96( 1.15)5.84( 0.87)-0.525.13( 1.10)5.69( 0.85)2.16*ICO5.70( 1.51)5.71( 1.45)0.035.73( 1.64)5.51( 1.92)-.47ARO6.10( 1.65)5.53( 1.84)-1.366.33( 1.60)5.38( 2.17)-1.92MRE6.93( 1.46)7.00( 1.22)0.217.60( 1.10)5.65( 1.73)-2.50*ORG7.26( 1.11)7.00( 1.16)-0.997.40( 1.10)7.03( 1.14)-1.25CONT5.43( 1.19)5.26( 1.11)-0.625.06( 1.36)5.27( 1.03)0.66COH8.36( 0.89)8.15( 0.79)-1.078.33( 0.802)8.00( 1.44)-1.10EXP6.06( 1.31)5.77( 1.39)-0.905.80( 1.49)5.48( 1.52)-.811.83( 2.58)3.06( 3.41)1.681.13( 1.27)2.27( 1.83)2.79**PSLE6.23( 4.43)11.24( 4.22)4.94***4.86( 3.12)6.75( 3.73)2.11*MCES** P 0.001, * P 0.05, ** P 0.01COH-Cohesion, EXP- Expressiveness, CONF-Conflict, IND- Independence, AO-Achievement-Orientation, ICO- Intellectual - Cultural Orientation,ARO-Active Recreational Orientation, MRE-Moral - Religious Emphasis, ORG-Organization, CONT-ControlPSLE- Presumptive Stressful Life Events Scale.MCES- Medical College Environment ScaleDiscussionOne of the significant findings emerged from thisstudy was that prevalence of psychiatric problemswere higher in medical entrants as compared tomedical outgoing students (32% Vs 25%).Therecan be several possible explanations of thisimportant observation. Medical entrants findmedical college as new environment to which theyhave to reorientation themselves or unlearn earlierschool milieu, which may be considered relativelyless competitive, more familiar to them and easyto cope. Similar results were obtained by Mahroonet al in 2017 in which the prevalence rate ofapproximately 40% was observed in students ofmedical university of Bahrain with higherprevalence of disorder in initial part of theeducation like year 1 as compared to later years(Year 5) [33]. Another study by Muzafar et al in2015 reported burnout of 35.9% according toCopenhagen Burnout Inventory in Lahore,Pakistan [34]. However, the study by Almojaliet alin 2017 reported a higher prevalence of 53.2% ofall types of stress by medical students of SaudiArabia. The reason for this disconcordance mightbe the difference in socio-cultural background anduse of different scale for assessment-KesslerPsychological Distress Scale (K10) [35].Current study depicted socio-demographic andpsychological determinants of emotional healthand ill health both in entrants and outgoingstudents. As regards to gender effect, both inmedical entrants and outgoing ones, it wasobserved that males in comparison to femaleswere more prone to psychiatric problems (33.33%Vs 26.66% & 26.13% Vs 21.42% respectively). Itmay be because females have more security thanmales in aspects including priority in hostelaccommodation. Females may also have positiveself-concept and self-esteem due to their entranceto glorious job of medicine and thus remainingfree from social role of housewife, while malesmay feel more social obligation of being solebread earner. The results of this study is incontradiction with studies by Mahroon et al in2017[33] and Muzafar et al in 2015 [34] wherefemales had more prevalence as compared tomales. The reason for this discordance might bethat the latter studies had more female subjectsrecruited and being an Arab country, femaleswould be facing different socio-cultural barriers,the reason of increased prevalence of psychiatricmorbidity quoted in their study also.It was also found that day-scholar medicalentrants had more psychiatric morbidity thanhostler, which could be due to proper personalitydevelopment of hostler which included severalRam Pratap Beniwal et al JMSCR Volume 05 Issue 12 December 2017Page 32029

JMSCR Vol 05 Issue 12 Page 32023-32033 Decemberfactors of adequate social exposure anddevelopment of interpersonal relationship amongpeers with similar results by Muzafar et al in2015[34]. It might be possible that day scholar hadadditional burden to travelling each day andfacing day to day family issues.However, family income played a vital role inoutgoing medical students as low and middlefamily income students were more prone todevelop mental ill health than those who belong tohigh income group. It may be that outgoingstudents may be concerned for their futuresettlements, deprived of their needs leading tofrustration and disappointment. Similar results instudy by Muzafar et al 2015 in which cause ofburn out was family responsibility. In Pakistan,married medical students and those belonging topoor families are expected to support theirfamilies financially. Such medical students mayfind it difficult to meet the demands of medicaleducation on the one hand and the financial andemotional support of their families on the other.Thus, the combined demands of medicaleducation, family, and the stress arising fromoccasional conflicts between these demands canexhaust the students to the level that they becomeburnt out [34].Mentally unhealthy medical students both atentrants and outgoing levels have scoredsignificantly higher on overall neuroticism leveland its constituent measures but this trend wasmore evident in entrants than outgoing students asit might be possible that outgoing studentsresolved some of their problems due to adaptationin their long medical educational process. Similarresults were obtained from review of literature byDerbye et al in 2005, where it was emphasizedthat first-year medical students were faced withthe challenges of being uprooted from family andfriends and adapting to a demanding new learningenvironment [3]. Rosiek et al in 2016 alsoconcluded that students toward the end of theireducation cope better with stress than studentsstarting their university Studies and the level ofperceived stress among students entering2017education is higher compared to the group ofstudents in their final year of studies [36].The role of personality disorders assessed throughICD-10 International Personality DisorderExamination was more in mentally unhealthymedical entrants than mentally unhealthy outgoingmedical students. We could not find any studyusing IPDE to assess personality disorders inmedical students. However, study by Burghi et al2017 used Myers‑ Briggs Type Indicator to assesspersonality profile and found statistically significant difference between extraversion‑ introversionpreferences and distress and burnout scores [26].Mentally healthy outgoing students used moreproblem solving and reward seeking and lessresigned acceptance as coping response thanmentally unhealthy ones. On the contrary,mentally healthy medical entrants significantlyemployed support seeking or guidance than theirunhealthy counterparts. Similar results werereported in a study by Imran et al in 2016 wherehealthy or approach coping responses wereemployed by mentally healthy students whereasavoidance coping response were more employedby unhealthy students. The most common copingstrategies adopted by students during stress werer

dissocial, impulsive, borderline, histrionic, anakastic, anxious and dependent personality disorder. 5. Coping Response Inventory [Moos, 1992] [30]. CRI was developed by Dr. Rudolf Moos, at Stanford University, California (in the year 1988, revised in 1992). The coping respon