Transcription

Economics briefsSix big ideas

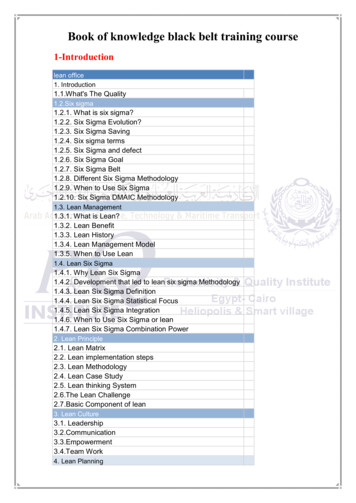

2Economics BriefsThe EconomistSix big economic ideasA collection of briefs on the discipline’s seminal papersIT IS easy enough to criticise economists: too superior, too blinkered, too oftenwrong. Paul Samuelson, one of the discipline’s great figures, once lampoonedstockmarkets for predicting nine out of the last five recessions. Economists, incontrast, barely ever see downturns coming. They failed to predict the 2007-08financial crisis.Yet this is not the best test of success. Much as doctors understand diseases butcannot predict when you will fall ill, economists’ fundamental mission is not toforecast recessions but to explain how the world works. During the summer of2016, The Economist ran a series of briefs on important economic theories that didjust that—from the Nash equilibrium, a cornerstone of game theory, to the MundellFleming trilemma, which lays bare the trade-offs countries face in their management of capital flows, exchange rates and monetary policy; from the financial-instability hypothesis of Hyman Minsky to the insights of Samuelson and WolfgangStolper on trade and wages; from John Maynard Keynes’s thinking on the fiscalmultiplier to George Akerlof’s work on information asymmetry. We have assembled these articles into this collection.The six breakthroughs are adverts not just for the value of economics, but alsofor three other things: theory, maths and outsiders. More than ever, economics today is an empirical discipline. But theory remains vital. Many policy failures mighthave been avoided if theoretical insights had been properly applied. The trilemmawas outlined in the 1960s, and the fiscal multiplier dates back to the 1930s; bothilluminate the current struggles of the euro zone and the sometimes self-defeatingpursuit of austerity. Nor is the body of economic theory complete. From “secularstagnation” to climate change, the discipline needs big thinkers as well as big data.It also needs mathematics. Economic papers are far too formulaic; modelsshould be a means, not an end. But the symbols do matter. The job of economistsis to impose mathematical rigour on intuitions about markets, economies and people. Maths was needed to formalise most of the ideas in our briefs.In economics, as in other fields, a fresh eye can also make a big difference. Newideas often meet resistance. Mr Akerlof’s paper was rejected by several journals,one on the ground that if it was correct, “economics would be different”. Recognition came slowly for many of our theories: Minsky stayed in relative obscurity until his death, gaining superstar status only once the financial crisis hit. Economistsstill tend to look down on outsiders. Behavioural economics has broken downone silo by incorporating insights from psychology. More need to disappear: likeanthropologists, economists should think more about how individuals’ decisionmaking relates to social mores; like physicists, they should study instability insteadof assuming that economies naturally self-correct.Information asymmetry4 Secrets and agentsGeorge Akerlof’s 1970 paper,“The Market for Lemons”, is afoundation stone of informationeconomics. The first in our serieson seminal economic ideasFinancial stability6 Minsky’s momentThe second article in our serieson seminal economic ideas looks atHyman Minsky’s hypothesis thatbooms sow the seeds of bustsTariffs and wages8 An inconvenient iota of truthThe third in our series looks at theStolper-Samuelson theoremFiscal multipliers10 Where does the buck stop?Fiscal stimulus, an ideachampioned by John MaynardKeynes, has gone in and out offashionGame theory12 Prison breakthroughThe fifth of our series on seminaleconomic ideas looks at the NashequilibriumThe Mundell-Fleming trilemma14 Two out of three ain’t badA fixed exchange rate, monetaryautonomy and the free flowof capital are incompatible,according to the last in our seriesof big economic ideasPublished since September 1843to take part in “a severe contest betweenintelligence, which presses forward, andan unworthy, timid ignorance obstructingour progress.”Editorial office:25 St James’s StreetLondon SW1 1HGTel: 44 (0) 20 7830 7000IllustrationRobert Samuel Hanson1

GRE prep on your termsNo classes, no schedules, no textbooks.Just interactive GRE prep that you canaccess anytime, anywhere.» Sign up for your free trial at econg.re/free1620

4BritainEconomicsBriefsThe Economist AprilThe Economist25th 2012Information asymmetrySecrets and agentsGeorge Akerlof’s 1970 paper, “The Market for Lemons”, is a foundation stone ofinformation economics. The first in our series on seminal economic ideasIN 2007 the state of Washington introduced a new rule aimed at making thelabour market fairer: firms were bannedfrom checking job applicants’ credit scores.Campaigners celebrated the new law as astep towards equality—an applicant with alow credit score is much more likely to bepoor, black or young. Since then, ten otherstates have followed suit. But when RobertClifford and Daniel Shoag, two economists,recently studied the bans, they found thatthe laws left blacks and the young withfewer jobs, not more.Before 1970, economists would nothave found much in their discipline tohelp them mull this puzzle. Indeed, theydid not think very hard about the role ofinformation at all. In the labour market, forexample, the textbooks mostly assumedthat employers know the productivity oftheir workers—or potential workers—and,thanks to competition, pay them for exactly the value of what they produce.You might think that research upending that conclusion would immediately becelebrated as an important breakthrough.Yet when, in the late 1960s, George Akerlofwrote “The Market for Lemons”, which didjust that, and later won its author a Nobelprize, the paper was rejected by three leading journals. At the time, Mr Akerlof wasan assistant professor at the Universityof California, Berkeley; he had only completed his PhD, at MIT, in 1966. Perhaps asa result, the American Economic Reviewthought his paper’s insights trivial. The Review of Economic Studies agreed. TheJournal of Political Economy had almost theopposite concern: it could not stomach thepaper’s implications. Mr Akerlof, now anemeritus professor at Berkeley and marriedto Janet Yellen, the chairman of the FederalReserve, recalls the editor’s complaint: “Ifthis is correct, economics would be different.”In a way, the editors were all right. MrAkerlof’s idea, eventually published in theQuarterly Journal of Economics in 1970,was at once simple and revolutionary. Suppose buyers in the used-car market valuegood cars—“peaches”—at 1,000, and sellers at slightly less. A malfunctioning usedcar—a “lemon”—is worth only 500 to buyers (and, again, slightly less to sellers). Ifbuyers can tell lemons and peaches apart,trade in both will flourish. In reality, buy-ers might struggle to tell the difference:scratches can be touched up, engine problems left undisclosed, even odometerstampered with.To account for the risk that a car is alemon, buyers cut their offers. They mightbe willing to pay, say, 750 for a car theyperceive as having an even chance of being a lemon or a peach. But dealers whoknow for sure they have a peach will reject such an offer. As a result, the buyersface “adverse selection”: the only sellerswho will be prepared to accept 750 willbe those who know they are offloading alemon.Smart buyers can foresee this problem. Knowing they will only ever be solda lemon, they offer only 500. Sellers oflemons end up with the same price asthey would have done were there no ambiguity. But peaches stay in the garage. Thisis a tragedy: there are buyers who wouldhappily pay the asking-price for a peach, ifonly they could be sure of the car’s quality.2 “information asymmetry” betweenThisbuyers and sellers kills the market.Is it really true that you can win aNobel prize just for observing that somepeople in markets know more than others? That was the question one journalistasked of Michael Spence, who, along withMr Akerlof and Joseph Stiglitz, was a jointrecipient of the 2001 Nobel award for theirwork on information asymmetry. His incredulity was understandable. The lemonspaper was not even an accurate description of the used-car market: clearly notevery used car sold is a dud. And insurershad long recognised that their customersmight be the best judges of what risks theyfaced, and that those keenest to buy insurance were probably the riskiest bets.Yet the idea was new to mainstreameconomists, who quickly realised that itmade many of their models redundant.Further breakthroughs soon followed, asresearchers examined how the asymmetry problem could be solved. Mr Spence’sflagship contribution was a 1973 papercalled “Job Market Signalling” that lookedat the labour market. Employers maystruggle to tell which job candidates arebest. Mr Spence showed that top workersmight signal their talents to firms by collecting gongs, like college degrees. Crucially, this only works if the signal is credible:if low-productivity workers found it easyto get a degree, then they could masquerade as clever types.This idea turns conventional wisdomon its head. Education is usually thoughtto benefit society by making workersmore productive. If it is merely a signalof talent, the returns to investment ineducation flow to the students, who earna higher wage at the expense of the lessable, and perhaps to universities, but not 1

Economics brief2 to society at large. One disciple of the idea,Bryan Caplan of George Mason University, is currently penning a book entitled“The Case Against Education”. (Mr Spencehimself regrets that others took his theoryas a literal description of the world.)Signalling helps explain what happened when Washington and those otherstates stopped firms from obtaining jobapplicants’ credit scores. Credit history is acredible signal: it is hard to fake, and, presumably, those with good credit scores aremore likely to make good employees thanthose who default on their debts. MessrsClifford and Shoag found that when firmscould no longer access credit scores, theyput more weight on other signals, likeeducation and experience. Because theseare rarer among disadvantaged groups, itbecame harder, not easier, for them to convince employers of their worth.Signalling explains all kinds of behaviour. Firms pay dividends to their shareholders, who must pay income tax on thepayouts. Surely it would be better if they retained their earnings, boosting their shareprices, and thus delivering their shareholders lightly taxed capital gains? Signallingsolves the mystery: paying a dividend is asign of strength, showing that a firm feelsno need to hoard cash. By the same token,why might a restaurant deliberately locatein an area with high rents? It signals to potential customers that it believes its goodfood will bring it success.Signalling is not the only way to overcome the lemons problem. In a 1976 paperMr Stiglitz and Michael Rothschild, another economist, showed how insurers might“screen” their customers. The essence ofscreening is to offer deals which wouldonly ever attract one type of punter.Suppose a car insurer faces two different types of customer, high-risk and lowrisk. They cannot tell these groups apart;only the customer knows whether he is asafe driver. Messrs Rothschild and Stiglitzshowed that, in a competitive market, insurers cannot profitably offer the samedeal to both groups. If they did, the premiums of safe drivers would subsidise payouts to reckless ones. A rival could offera deal with slightly lower premiums, andslightly less coverage, which would peelaway only safe drivers because risky onesprefer to stay fully insured. The firm, leftonly with bad risks, would make a loss.(Some worried a related problem wouldafflict Obamacare, which forbids American health insurers from discriminatingagainst customers who are already unwell:if the resulting high premiums were to deter healthy, young customers from signingup, firms might have to raise premiumsfurther, driving more healthy customersaway in a so-called “death spiral”.)The car insurer must offer two deals,The Economist 5making sure that each attracts only thecustomers it is designed for. The trick is tooffer one pricey full-insurance deal, andan alternative cheap option with a sizeable deductible. Risky drivers will balkat the deductible, knowing that there isa good chance they will end up payingit when they claim. They will fork out forexpensive coverage instead. Safe driverswill tolerate the high deductible and pay alower price for what coverage they do get.This is not a particularly happy resolution of the problem. Good drivers are stuckwith high deductibles—just as in Spence’smodel of education, highly productiveworkers must fork out for an education inorder to prove their worth. Yet screening isin play almost every time a firm offers itscustomers a menu of options.Airlines, for instance, want to milk richcustomers with higher prices, withoutdriving away poorer ones. If they knewthe depth of each customer’s pockets inadvance, they could offer only first-classtickets to the wealthy, and better-valuetickets to everyone else. But because theymust offer everyone the same options,they must nudge those who can affordit towards the pricier ticket. That meansdeliberately making the standard cabinuncomfortable, to ensure that the onlypeople who slum it are those with slimmer wallets.Hazard undercuts EdenAdverse selection has a cousin. Insurershave long known that people who buy insurance are more likely to take risks. Someone with home insurance will check theirsmoke alarms less often; health insuranceencourages unhealthy eating and drinking.Economists first cottoned on to this phenomenon of “moral hazard” when Kenneth Arrow wrote about it in 1963.Moral hazard occurs when incentivesgo haywire. The old economics, noted MrStiglitz in his Nobel-prize lecture, paid considerable lip-service to incentives, but hadremarkably little to say about them. In acompletely transparent world, you neednot worry about incentivising someone,because you can use a contract to specifytheir behaviour precisely. It is when information is asymmetric and you cannot observe what they are doing (is your tradesman using cheap parts? Is your employeeslacking?) that you must worry about ensuring that interests are aligned.Such scenarios pose what are knownas “principal-agent” problems. How can aprincipal (like a manager) get an agent (likean employee) to behave how he wants,when he cannot monitor them all thetime? The simplest way to make sure thatan employee works hard is to give himsome or all of the profit. Hairdressers, forinstance, will often rent a spot in a salonand keep their takings for themselves.But hard work does not always guarantee success: a star analyst at a consultingfirm, for example, might do stellar workpitching for a project that nonethelessgoes to a rival. So, another option is to pay“efficiency wages”. Mr Stiglitz and CarlShapiro, another economist, showed thatfirms might pay premium wages to makeemployees value their jobs more highly.This, in turn, would make them less likelyto shirk their responsibilities, because theywould lose more if they were caught andgot fired. That insight helps to explain afundamental puzzle in economics: whenworkers are unemployed but want jobs,why don’t wages fall until someone iswilling to hire them? An answer is thatabove-market wages act as a carrot, the resulting unemployment, a stick.And this reveals an even deeper point.Before Mr Akerlof and the other pioneersof information economics came along,the discipline assumed that in competitive markets, prices reflect marginal costs:charge above cost, and a competitor willundercut you. But in a world of information asymmetry, “good behaviour is drivenby earning a surplus over what one couldget elsewhere,” according to Mr Stiglitz. Thewage must be higher than what a workercan get in another job, for them to want toavoid the sack; and firms must find it painful to lose customers when their product isshoddy, if they are to invest in quality. Inmarkets with imperfect information, pricecannot equal marginal cost.The concept of information asymmetry, then, truly changed the discipline.Nearly 50 years after the lemons paperwas rejected three times, its insights remain of crucial relevance to economists,and to economic policy. Just ask anyyoung, black Washingtonian with a goodcredit score who wants to find a job. n

6BritainEconomicsBriefsThe Economist AprilThe Economist25th 2012Financial stabilityMinsky’s momentThe second article in our series on seminal economic ideas looks at Hyman Minsky’s hypothesis that booms sow the seeds of bustsFROM the start of his academic careerin the 1950s until 1996, when he died,Hyman Minsky laboured in relative obscurity. His research about financial crisesand their causes attracted a few devotedadmirers but little mainstream attention:this newspaper cited him only once whilehe was alive, and it was but a brief mention. So it remained until 2007, when thesubprime-mortgage crisis erupted in America. Suddenly, it seemed that everyone wasturning to his writings as they tried to makesense of the mayhem. Brokers wrote notesto clients about the “Minsky moment” engulfing financial markets. Central bankersreferred to his theories in their speeches.And he became a posthumous media star,with just about every major outlet givingcolumn space and airtime to his ideas. TheEconomist has mentioned him in at least30 articles since 2007.If Minsky remained far from the limelight throughout his life, it is at least in partbecause his approach shunned academicconventions. He started his universityeducation in mathematics but made little use of calculations when he shifted toeconomics, despite the discipline’s grow-ing emphasis on quantitative methods. Instead, he pieced his views together in hisessays, lectures and books, including oneabout John Maynard Keynes, the economist who most influenced his thinking.He also gained hands-on experience, serving on the board of Mark Twain Bank in StLouis, Missouri, where he taught.Having grown up during the Depression, Minsky was minded to dwell ondisaster. Over the years he came back tothe same fundamental problem again andagain. He wanted to understand why financial crises occurred. It was an unpopular focus. The dominant belief in the latterhalf of the 20th century was that marketswere efficient. The prospect of a full-blowncalamity in developed economies soundedfar-fetched. There might be the occasionalstockmarket bust or currency crash, butmodern economies had, it seemed, vanquished their worst demons.Against those certitudes, Minsky, anowlish man with a shock of grey hair, developed his “financial-instability hypothesis”. It is an examination of how longstretches of prosperity sow the seeds ofthe next crisis, an important lens for un-derstanding the tumult of the past decade.But the history of the hypothesis itself isjust as important. Its trajectory from themargins of academia to a subject of mainstream debate shows how the study ofeconomics is adapting to a much-changedreality since the global financial crisis.Minsky started with an explanation ofinvestment. It is, in essence, an exchangeof money today for money tomorrow. Afirm pays now for the construction of afactory; profits from running the facilitywill, all going well, translate into moneyfor it in coming years. Put crudely, moneytoday can come from one of two sources:the firm’s own cash or that of others (forexample, if the firm borrows from a bank).The balance between the two is the keyquestion for the financial system.Minsky distinguished between threekinds of financing. The first, which hecalled “hedge financing”, is the safest:firms rely on their future cashflow to repay all their borrowings. For this to work,they need to have very limited borrowings and healthy profits. The second, speculative financing, is a bit riskier: firms relyon their cashflow to repay the interest ontheir borrowings but must roll over theirdebt to repay the principal. This shouldbe manageable as long as the economyfunctions smoothly, but a downturn couldcause distress. The third, Ponzi financing,is the most dangerous. Cashflow coversneither principal nor interest; firms arebetting only that the underlying asset willappreciate by enough to cover their liabilities. If that fails to happen, they will be leftexposed.Economies dominated by hedge financing—that is, those with strong cashflows and low debt levels—are the moststable. When speculative and, especially,Ponzi financing come to the fore, financialsystems are more vulnerable. If asset values start to fall, either because of monetary tightening or some external shock, themost overstretched firms will be forcedto sell their positions. This further undermines asset values, causing pain for evenmore firms. They could avoid this troubleby restricting themselves to hedge financing. But over time, particularly when theeconomy is in fine fettle, the temptation totake on debt is irresistible. When growthlooks assured, why not borrow more?Banks add to the dynamic, lowering theircredit standards the longer booms last. Ifdefaults are minimal, why not lend more?Minsky’s conclusion was unsettling. Economic stability breeds instability. Periodsof prosperity give way to financial fragility.With overleveraged banks and nomoney-down mortgages still fresh in themind after the global financial crisis, Minsky’s insight might sound obvious. Ofcourse, debt and finance matter. But for 1

Economics brief2 decades the study of economics paid little heed to the former and relegated thelatter to a sub-discipline, not an essentialelement in broader theories. Minsky was amaverick. He challenged both the Keynesian backbone of macroeconomics and aprevailing belief in efficient markets.It is perhaps odd to describe his ideasas a critique of Keynesian doctrine whenMinsky himself idolised Keynes. But hebelieved that the doctrine had strayed toofar from Keynes’s own ideas. Economistshad created models to put Keynes’s wordsto work in explaining the economy. Noneis better known than the IS-LM model,largely developed by John Hicks and AlvinHansen, which shows the relationship between investment and money. It remainsa potent tool for teaching and for policyanalysis. But Messrs Hicks and Hansenlargely left the financial sector out of thepicture, even though Keynes was keenlyaware of the importance of markets. ToMinsky, this was an “unfair and naive representation of Keynes’s subtle and sophisticated views”. Minsky’s financial-instability hypothesis helped fill in the holes.His challenge to the prophets of efficient markets was even more acute.Eugene Fama and Robert Lucas, amongothers, persuaded most of academia andpolicymaking circles that markets tendedtowards equilibrium as people digestedall available information. The structure ofthe financial system was treated as almostirrelevant. In recent years, behaviouraleconomists have attacked one plank ofefficient-market theory: people, far frombeing rational actors who maximise theirgains, are often clueless about what theywant and make the wrong decisions. Butyears earlier Minsky had attacked another:deep-seated forces in financial systemspropel them towards trouble, he argued,with stability only ever a fleeting illusion.Outside-inYet as an outsider in the sometimes cloistered world of economics, Minsky’s influence was, until recently, limited. Investorswere faster than professors to latch ontohis views. More than anyone else it wasPaul McCulley of PIMCO, a fund-management group, who popularised his ideas.He coined the term “Minsky moment” todescribe a situation when debt levels reachbreaking-point and asset prices across theboard start plunging. Mr McCulley initiallyused the term in explaining the Russian financial crisis of 1998. Since the global turmoil of 2008, it has become ubiquitous.For investment analysts and fund managers, a “Minsky moment” is now virtuallysynonymous with a financial crisis.Minsky’s writing about debt and thedangers in financial innovation had thegreat virtue of according with experience.The Economist 7But this virtue also points to what somemight see as a shortcoming. In trying topaint a more nuanced picture of the economy, he relinquished some of the potencyof elegant models. That was fine as far ashe was concerned; he argued that generalisable theories were bunkum. He wantedto explain specific situations, not economics in general. He saw the financial-instability hypothesis as relevant to the case ofadvanced capitalist economies with deep,sophisticated markets. It was not meant tobe relevant in all scenarios. These days, forexample, it is fashionable to ask whetherChina is on the brink of a Minsky momentafter its alarming debt growth of the pastdecade. Yet a country in transition fromsocialism to a market economy and withan immature financial system is not whatMinsky had in mind.Shunning the power of equations andmodels had its costs. It contributed to Minsky’s isolation from mainstream theories.Economists did not entirely ignore debt,even if they studied it only sparingly.Some, such as Nobuhiro Kiyotaki andBen Bernanke, who would later becomechairman of the Federal Reserve, looked athow credit could amplify business cycles.Minsky’s work might have complementedtheirs, but they did not refer to it. It was asif it barely existed.Since Minsky’s death, others havestarted to correct the oversight, grafting histheories onto general models. The LevyEconomics Institute of Bard College inNew York, where he finished his career(it still holds an annual conference in hishonour), has published work that incorpo-rates his ideas in calculations. One Levypaper, published in 2000, developed aMinsky-inspired model linking investmentand cashflow. A 2005 paper for the Bankfor International Settlements, a forum forcentral banks, drew on Minsky in buildinga model of how people assess their assetsafter making losses. In 2010 Paul Krugman,a Nobel prize-winning economist whois best known these days as a New YorkTimes columnist, co-authored a paper thatincluded the concept of a “Minsky moment” to model the impact of deleveraging on the economy. Some researchers arealso starting to test just how accurate Minsky’s insights really were: a 2014 discussion paper for the Bank of Finland lookedat debt-to-cashflow ratios, finding them tobe a useful indicator of systemic risk.Debtor’s prismStill, it would be a stretch to expect the financial-instability hypothesis to become anew foundation for economic theory. Minsky’s legacy has more to do with focusingon the right things than correctly structuring quantifiable models. It is enough toobserve that debt and financial instability,his main preoccupations, have becomesome of the principal topics of inquiryfor economists today. A new version ofthe “Handbook of Macroeconomics”, aninfluential survey that was first publishedin 1999, is in the works. This time, it willmake linkages between finance and economic activity a major component, withat least two articles citing Minsky. As MrKrugman has quipped: “We are all Minskyites now.”Central bankers seem to agree. In aspeech in 2009, before she became headof the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen saidMinsky’s work had “become requiredreading”. In a 2013 speech, made whilehe was governor of the Bank of England,Mervyn King agreed with Minsky’s viewthat stability in credit markets leads to exuberance and eventually to instability. MarkCarney, Lord King’s successor, has referredto Minsky moments on at least two occasions.Will the moment last? Minsky’s owntheory suggests it will eventually peterout. Economic growth is still shaky andthe scars of the global financial crisis visible. In the Minskyan trajectory, this iswhen firms and banks are at their mostcautious, wary of repeating past mistakesand determined to fortify their balancesheets. But in time, memories of the 2008turmoil will dim. Firms will again race toexpand, banks to fund them and regulators to loosen constraints. The warningsof Minsky will fade away. The further wemove on from the last crisis, the less wewant to hear from those who see anotherone coming. n

8BritainEconomicsBriefsThe Economist AprilThe Economist25th 2012Tariffs and wagesAn inconvenient iota of truthThe third in our series looks at the Stolper-Samuelson theoremIN AUGUST 1960 Wolfgang Stolper, anAmerican economist working for Nigeria’s development ministry, embarked on atour of the country’s poor northern region,a land of “dirt and dignity”, long ruled byconservative emirs and “second-rate British civil servants who didn’t like business”.In this bleak commercial landscape onestrange flower bloomed: Kaduna TextileMills, built by a Lancashire firm a few yearsbefore, employed 1,400 people paid as little as 4.80 ( 6.36) a day in today’s prices.And yet it required a 90% tariff to compete.Skilled labour was scarce: the mill hadfound only six northerners worth trainingas foremen (three failed, two were “soso”, one was “superb”). Some employeeswalked ten miles to work, others carriedthe hopes of mendicant relatives on theirbacks. Many quit, adding to the cost of finding and training replacements. Those whostayed were often too tired, inexperiencedor ill-educated to maintain the machinesproperly. “African labour is the worst paidand most expensive in the world,” Stolpercomplained.He concluded that Nigeria was not yetready for large-scale industry. “Any indus-try which required high duties impoverished the country and wasn’t worth having,” he believed. This was not a popularview among his fellow planners. But Stolper’s ideas carried unusual weight. He wasa successful schmoozer, able to drink likea fish. He liked “getting his hands dirty” inempirical work. And his trump card, whichwon him the respect of friends and the earof superiors, was the “Stolper-Samuelsontheorem” that bore his name.The

2 Economics Briefs The Economist I T IS easy enough to criticise economists: too superior, too blinkered, too often wrong. Paul Samuelson, one of the discipline’s great figures, once lampoonedFile Size: 2MB