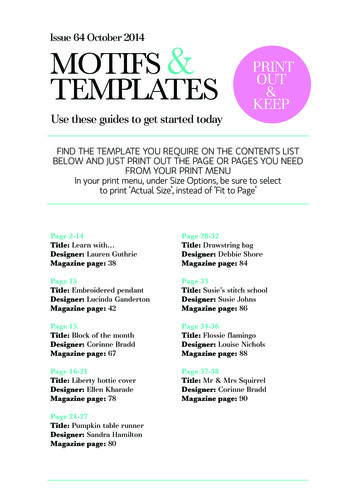

Transcription

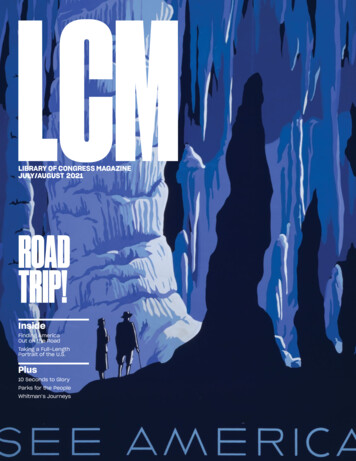

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINEJULY/AUGUST 2021ROADTRIP!InsideFinding AmericaOut on the RoadTaking a Full-LengthPortrait of the U.S.Plus10 Seconds to GloryParks for the PeopleWhitman’s Journeys

FEATURES121420The Olmsted family createdan amazing array ofoutdoor spaces.A journey through anAmerican phenomenon: thefamily vacation by car.Photographer Carol M.Highsmith is taking a fulllength portrait of the U.S.Parks for the PeopleLIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINEFinding AmericaOn the Road Again A neon sign in Amarillo,Texas, marks the pathof historic Route 66through town. CarolM. Highsmith Archive/Prints and PhotographsDivision

On the cover: This poster for the United States Travel Bureau, createdby Alexander Dux in the 1930s under the auspices of the federal WorksProgress Administration, promoted tourism across America. Prints andPhotographs DivisionLIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINEJULY / AUGUST 2021VOL. 10 NO. 4Mission of theLibrary of CongressThe Library’s mission is to engage,inspire and inform Congressand the American people with auniversal and enduring source ofknowledge and creativity.Library of Congress Magazine isissued bimonthly by the Office ofCommunications of the Libraryof Congress and distributedfree of charge to publiclysupported libraries and researchinstitutions, donors, academiclibraries, learned societies andallied organizations in the UnitedStates. Research institutions andeducational organizations in othercountries may arrange to receiveLibrary of Congress Magazine onan exchange basis by applying inwriting to the Library’s Directorfor Acquisitions and BibliographicAccess, 101 Independence Ave.S.E., Washington DC 205404100. LCM is also available onthe web at loc.gov/lcm/. Allother correspondence shouldbe addressed to the Office ofCommunications, Library ofCongress, 101 Independence Ave.S.E., Washington DC 20540-1610.DEPARTMENTS2Trending3Off the Shelf4Online Offerings6Technology7Extremes8Page from the Past10Curator’s Picks24My Job25News Briefs26Shop the Library27Support the Library28Last Word46news@loc.govloc.gov/lcmISSN 2169-0855 (print)ISSN 2169-0863 (online)Carla HaydenLibrarian of Congress8April SlaytonExecutive EditorMark HartsellEditorAshley JonesDesignerShawn MillerPhoto EditorContributorsBarbara BairAndrew DavisJan GrenciMegan HarrisJosh LevySahar KazmiRoxana RobinsonCONNECT ON28loc.gov/connectJULY/AUGUST 2021 LOC.GOV/LCM1

TRENDING10 SECONDS TOGLORY Top: William HarrisonDillard won the 100meters sprint in thisphoto finish at the 1948Olympics in London.Above: Dillard, a WorldWar II veteran, as heappeared aroundthe time he donatedservice-related materialto the Veterans HistoryProject. Smith Archive/Alamy Stock Photo,Veterans History ProjectA WWII veteran won gold atthe London Olympics in thefirst photo finish.London, summer 1948. All eyes are on thefirst Olympic Games held since 1936. Afteryears of war, countries from around theworld meet not on the battlefield, but onthe track, in the swimming pool, inside theboxing ring.At Wembley Stadium, six sprinters crouchon the track for the finals of the 100-meterdash. The gun sounds, and in 10 secondsit’s over. The race is so close that, for thefirst time in history, a photograph is used todeclare the winner.But the photo makes it clear: WilliamHarrison Dillard won the gold; he is the“fastest man alive.”The feat is all the more stirring because,three years earlier, Dillard had been dodgingmortar fire in Italy as part of the U.S. Army’s92nd Infantry Division, a segregated unitknown as the “Buffalo Soldiers.”Today, Dillard’s story, told in his own words,is preserved at the Library in the collectionsof the Veterans History Project.Born in Cleveland, Dillard attended thesame high school as legendary Olympian2LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINEJesse Owens and went to Baldwin WallaceCollege on a track scholarship. During hissophomore year, he was drafted and laterassigned to the 92nd.By 1944, he was in combat in Italy. Forsix months, the 92nd slowly advanced,liberating towns as they went. In hisVeterans History Project interview, Dillardrecalls mortar fire, minefields, the braveryof his comrades, and Italian civilians, theirvillages destroyed, begging U.S. servicemenfor food.With the end of the war, Dillard’s focusturned from survival to running. Whilestationed in Europe during the occupation,he won four gold medals at the GIOlympics. At the London Games, he wonthe 100-meter dash and the 4x100 relay.Four years later, at the Helsinki Games, hewon the 110-meter hurdles and anotherrelay — making him a four-time Olympic goldmedalist, just like his idol, Owens.Grit and resilience are among the qualitiesthat make Olympic athletes great — manyovercome formidable challenges just toreach the games. Few survive the rigors,deprivation and dangers of combat only toarrive, like Dillard, at the medals podium amere three years later.—Megan Harris is a reference specialist inthe Veterans History Project.MORE INFORMATIONVeterans History Projectloc.gov/vets/

OFF THE SHELFthe Folklife Center,and interviews sheconducted withowners of businesseslisted in the GreenBook are available onthe Library’s website.THE GREEN BOOKThis guide helped Blacktravelers navigate the countryin safety and with dignity.For African American travelers of the mid20th century, discrimination had no borders.At that time, open and often legaldiscrimination made it difficult for Blacks totravel around not just the South but muchof the United States because they couldn’teat, sleep or buy gas at most white-ownedbusinesses.The Negro Motorist Green Book helpedthem do so in safety and with dignity: Thebook identified businesses — lodgings,restaurants, gas stations and others —friendly to Black travelers so they could getservice along the road.“The gift of the Green Book was that it reallydid show the communities where Blackculture was happening, where there wereBlack-owned businesses where you knewyou could get services,” said CandacyTaylor, author of “Overground Railroad: TheGreen Book and the Roots of Black Travel inAmerica,” in an interview with the Library’sAmerican Folklife Center. “It was literally alifesaver.”Taylor’s research for the book was fundedin part by an Archie Green fellowship fromThe Green Book wasfounded by Harlempostal worker Victor HugoGreen in 1936 and overthe next three decadesbecame so indispensablethat it earned the nickname“the Bible of Black travel.”The passage of the CivilRights Act of 1964, however,made the book less necessary, and in 1967it ceased publication.Today, historical copies of the Green Bookprovide a record of places that playedan important role in the lives of bothordinary people and great figures in AfricanAmerican history. Martin Luther King Jr.previewed his “I Have a Dream” speechfor associates at the Hampton House inMiami and got haircuts at the Ben MooreHotel in Montgomery, Alabama. Cassius Claycelebrated his upset of Sonny Liston — andmet with Malcolm X — at the Hampton’s café. African Americanpatrons fill the Dew DropInn, a nightclub listed inthe New Orleans sectionof the Green Book.The club hosted suchgreat musicians as RayCharles, James Brown,Etta James and LittleRichard, who wrote asong about the place.American Folklife CenterFive decades after it ceased publication,the Green Book still stands as a milestonefor African Americans along the road tofreedom.MORE INFORMATIONThe Green Book: Documenting African AmericanEntrepreneursgo.usa.gov/xHXNDPodcast with Candacy Taylorgo.usa.gov/xHnxYJULY/AUGUST 2021 LOC.GOV/LCM3

ONLINE OFFERINGSTHEY’RE A TRIPTravel posters from the goldenage still inspire viewers toexplore.Great travel art takes you places, even whenyou haven’t left home. Just by looking, onecan feel the color and excitement of TimesSquare, the sea air in a lush garden in PuertoRico, the spray from an eruption of OldFaithful in Yellowstone National Park.The Library holds thousands of travelposters designed to inspire viewers tovisit points of interest, to revel in holidayactivities and to enjoy the journey itselfthrough various modes of transportation.Many date from the golden age of the travelposter, which began in the 1920s, whentravel by land or sea was more commonthan travel by air. The golden age ended inthe 1960s, when photographic imagery andother forms of advertising began to be usedmore than graphically designed posters.A selection of the Library’s collection oftravel posters are available online in theFree to Use and Reuse set; most of thesewere produced by the Work ProjectsAdministration between 1936 and 1943.These posters, some created for the UnitedStates Travel Bureau, celebrated nationalparks and encouraged all to “See America”— the catchphrase on a number of them.The bureau was established in 1937 topromote travel within the United States. Clockwise fromtop left: Vintagetravel posterspresent an abstractview of TimesSquare; provide alook across the bayin San Juan, PuertoRico; and showYellowstone’s OldFaithful geyser inmid-eruption. Printsand PhotographsDivision4LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINEGifts, purchases and copyright deposit haveadded to the variety of travel posters in thebroader collection. Eye-catching examplesmade in the U.S. and in other countriesencourage exploration of places near andfar — still today, an inspiration to pack a bagand go explore.—Jan Grenci is a reference specialist in thePrints and Photographs Division.MORE INFORMATIONFree to Use and Reuse: Travel Postersloc.gov/free-to-use/travel-posters/

JULY/AUGUST 2021 LOC.GOV/LCM5

TECHNOLOGY Trumpeter DizzyGillespie (right)watches EllaFitzgerald performat a nightclub in1947 in this classicphoto from theWilliam P. GottleibCollection. MusicDivisionTREASURES IN THEPALM OF A HANDMobile app makes access tocollections easy.For years, mobile libraries built in busesand RVs have expanded the reach andaccessibility of library resources beyond theconfines of brick and mortar buildings.In today’s age of apps for everything,the Library has imagined an even moreconvenient way to put its many treasures inthe hands of patrons — and it’s available 24hours a day.The LOC Collections mobile app for iOS andAndroid allows users to read completebooks, explore presidential papers, viewiconic photos and maps and save and sharemore than a million unique items from theLibrary’s rich digital collections.Created by the Library’s own softwaredevelopment experts, the LOC Collectionsapp was designed to give users a distinctlypersonal experience with Library materials.The app’s intuitive interface allows readersto easily browse through thousands ofcollections, explore descriptive notescomposed by librarians and archivistsand even curate their favorite items intopersonalized galleries.Library designers and developers workedclosely with patrons to test and release anumber of enhancements to improve theuser experience of the app and make iteven simpler to discover historical gemsfrom the Library’s collections. In additionto a full-screen image and PDF viewer thatenables easier reading on smaller devices,the LOC Collections app includes landscapereading options and a variety of accessibilityupdates to support all users.Curious users can uncover even more witheasy-access links that jump straight fromthe app to the Library’s website to surfacerelated collections, citation details and rightsand access information.—Sahar Kazmi is a writer-editor in the Officeof the Chief Information Officer.MORE INFORMATIONLOC Collections Apploc.gov/apps6LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE

EXTREMESHEAVY METALA deeply felt tribute to abridge in a book made ofaluminum.The iconic suspension bridge that connectsBrooklyn and Manhattan has inspired greatart and artists since the day it openednearly 140 years ago.Frank Sinatra sang about the BrooklynBridge. Georgia O’Keeffe and Andy Warholpainted it. Walker Evans photographed it,and Hart Crane wrote an epic poem about it.The bridge makes countless cameos in film— “It Happened in Brooklyn,” “Moonstruck,”“Spider-Man” and many others.To those works, add Donald Glaister’s 2002book “Brooklyn Bridge A Love Song,”an homage that is as innovative as it isheartfelt. The book, along with other worksby Glaister, are held by the Library’s RareBook and Special Collections Division.Ordinary materials wouldn’t do for a volumeabout such an iconic structure. So, Glaister,a master bookbinder, built his book out ofstuff more befitting the subject: aluminum,wire, sand, acrylic paint, aluminum tape andpolyester film. The volume itself is housed ina felt-lined aluminum box.Glaister made the book’s pages outof sanded aluminum, and on them heemblazoned a poem he had written intribute and his own painted “portraits” of thespan. Granite and limestone towers loomagainst the rose and blue of a morning sky.Shifting colors evoke different times of day,and abstract forms suggest the massivenetwork of cables that holds the deck some127 feet above the East River. Master bookbinderDonald Glaisterconstructed this homageto the Brooklyn Bridgefrom aluminum, wire,sand, acrylic paintand other materials.Rare Book and SpecialCollectionsThe Brooklyn Bridge — designed by JohnRoebling and completed by his son,Washington Roebling in 1883 — was thelongest suspension bridge in the world atthe time of its opening. It has experiencedmuch since.Glaister’s verse — like the materials thatcarry it — celebrates the bridge’s strengthand timeless grace:The Bridge endures.She has seen it all. Peace and war,plenty and need, vice and honor,the sublime and the horrific.She stands watch and does not yield.The gracious lady stands in the riverand does not yield.—Mark HartsellJULY/AUGUST 2021 LOC.GOV/LCM7

PAGE FROM THE PAST Walt Whitman tracedhis journeys around theU.S. and in Canada inred on the map at right.Prints and PhotographsDivision, ManuscriptDivisionWHITMAN’SJOURNEYSThe great poet recorded histrips across America andCanada on this map.Poet and essayist Walt Whitman loved citystreets, the beauty of a ferry crossing,whirling gulls and the outdoors. He collectedleaves and pressed them into a scrapbookand made the sea, the sky, stars, woods,marshes and the melodic calls of birds thesubject matter of his poetry.Strongly influenced by transcendentalistphilosophy, he traveled sweepingly in hismind’s eye to geographic regions across theUnited States and around the globe, writingof farms and fields and redwood groveswitnessed only in his imagination.The travel lines inked on this railroad mapshow actual journeys he took into thehinterland, to New Orleans in 1848 while anewspaperman, to Washington, D.C., wherehe worked as a civil servant from 1863 to1873, across the Great Plains to the ColoradoRockies in 1879, up into Canada in 1880, andto New England in 1872 and again to visitRalph Waldo Emerson in 1881.—Barbara Bair is a historian in theManuscript Division.8LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE

CURATOR’S PICKSOUR PICK OF THEPARKSLace up your hiking boots fora trip through favorite nationalparks-related items fromLibrary collections.MAPPING THE CANYONGeographers knew little about theGrand Canyon until the middle of the19th century. First published in 1882,“Tertiary History of the Grand CañonDistrict” summarized what was knownin a beautiful way. Illustrations byThomas Moran and William Holmescapture the canyon’s grandeur,and maps detail its topography andgeology. The volume, produced byClarence Dutton and issued by theU.S. Geological Survey, served as thefoundation upon which later mapping ofthe canyon was based. The Geographyand Map Division holds the illustratedatlas that accompanied Dutton’s longerreport.Geography and Map DivisionTHE FIRST PARKThe Yellowstone region was littleexplored before Ferdinand Haydenled an expedition into its wilds in1871. A report by Hayden to Congressrevealed an unimaginable land —erupting geysers, boiling hot springs,bubbling mudpots, raging waterfalls— and helped convince Congress tomake Yellowstone our first nationalpark, in 1872. In Hayden’s party wasartist Thomas Moran, who capturedYellowstone’s wonders in workssuch as this view of a geyser basin,reproduced in a chromolithograph by L.Prang & Co.Prints and Photographs Division10LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE

YELLOWSTONE, ON FILMOnly a hardy few made the arduousjourney to remote Yellowstone in itsfirst years as a park. That began tochange in 1883, when a spur of theNorthern Pacific Railroad arrived at thepark’s northern boundary. From there,eager tourists boarded stagecoachesand rode out to see Yellowstone’swonders. Films made by the ThomasEdison company in the 1890s captureglimpses of this: Tourists arrive bycoach at Mammoth Hot Springs andwave to the camera as they head offinto the park, ready for adventure.Motion Picture, Broadcasting andRecorded Sound DivisionCAMPING WITH TEDDYIn 1903, a three-day camping tripin Yosemite led by naturalist JohnMuir helped change the course ofconservation. Muir’s backcountrycompanion was President TheodoreRoosevelt, who loved the outdoorsand was interested in conservation.The outing made a deep impressionon the president: Roosevelt went onto create five new national parks andsign the Antiquities Act, which he usedto protect the Grand Canyon and otherwilderness areas. Here, Roosevelt andMuir take in Yosemite Falls from GlacierPoint — one of the most glorious viewsin all of the national parks.Prints and Photographs DivisionPARKS IN POSTERSIn the 1930s and ’40s, the federalWork Projects Administration (WPA)commissioned posters designedto publicize exhibits, theatricalproductions, educational programs —and the beauty of America’s nationalparks. The Library holds the largestcollection of WPA posters, some ofwhich capture the parks in their wildglory: iconic Old Faithful geyser eruptsin Yellowstone, sandstone cliffs towerover Zion, steam pours from Lassenvolcano and, here, bighorn sheep poseagainst a backdrop of mountain peaksand burnt orange sky.Prints and Photographs DivisionJULY/AUGUST 2021 LOC.GOV/LCM11

PARKSFOR THEPEOPLEThe Olmsted family createdan amazing array of outdoorspaces across America.BY BARBARA BAIR12LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE

Frederick Law Olmsted(left) and Calvert Vauxcreated the design forCentral Park in New YorkCity (opposite) from1857 to 1861. Prints andPhotographs DivisionFrederick Law Olmsted and his sonshad a far-seeing vision for the Americanlandscape, of green spaces made for themasses, of parks and public grounds thatwould offer natural beauty and spiritualhaven in the heart of big, bustling cities.Over the course of two generations, theOlmsteds helped forge the professions ofurban planning and landscape architecture.They were pivotal in the design of a myriadof residential communities, city parks andgrounds of public and private buildingsthat remain in use across the nation.The Olmsted philosophy stressing theimportance of shareable green space andthe benefits for health, spiritual renewal anddemocracy through access to the outdoorsstill abides.The Library is home to Olmsted’s papersand the records of the Olmsted Associatesfirm. As a young man, Olmsted apprenticedand learned engineering, garden design andhorticultural techniques. He traveled abroadand to the Deep South and the West. Heworked as an organic farmer, journalist andadministrator before embracing landscapearchitecture as his life’s work.Olmsted is best known for his 1857–1861design, with Calvert Vaux, of Central Park inNew York City. Over the next century, he andhis successors shaped an amazing arrayof public parks and parkways, suburbancommunities, campuses, cemeteries,estates and grounds for hospitals andgovernment buildings, from the EmeraldNecklace of Boston to parks in Seattle, theBiltmore estate of North Carolina, the U.S.Capitol and Mount Royal in Montreal.Central Park was a visionary prototypecrafted and shaped into a variety oflandscapes: craggy rocks, meadows,woodlands and ponds, carriage paths,walking trails, arched bridges and apromenade and plaza — all intended toevoke different feelings and uses.This “Park for the People” was designed,Olmsted said, for working girls, urbanresidents and tourists of various faiths andclasses to experience scenic outdoors ina gregarious way. The park helped visitorsforget their workaday worlds, giving thema space to meet friends, play games, walk,find solitude, picnic with toddlers and courtlovers along tree-lined lanes.It would bring the same restorative beautyand benefit to a public citizenry that couldotherwise only be enjoyed in rarely visitedcountryside or reserved to the privateprivilege of the well-to-do. It provided a wayto escape, but also to find oneself, in anenvironment where everything appearedto be wondrously natural and yet wasmeticulously planned, civil engineered andplanted.In the 20th century, Olmsted’s sons JohnCharles Olmsted and Frederick (Rick) LawOlmsted Jr. carried on their father’s legacythrough the Olmsted Brothers/OlmstedAssociates firm.A member of the McMillan Commission andU.S. Commission of Fine Arts in Washington,D.C., Rick Olmsted helped shape the NationalMall, East and West Potomac Park, RockCreek Park, Theodore Roosevelt Island, theU.S. Arboretum and the National Zoo astravel destinations. He went on to consult forthe national park and California state parkssystems.The Library is partnering with the NationalAssociation for Olmsted Parks andother organizations and conservanciesto celebrate the 200th anniversary ofOlmsted’s birth in 2022 — a tribute to theidea of public spaces in America.MORE INFORMATIONPapers of Frederick Law Olmstedgo.usa.gov/xH3paJULY/AUGUST 2021 LOC.GOV/LCM13

FINDINGAMERICA14LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE

ON THE ROADA journey through a quintessentiallyAmerican phenomenon, the familyvacation by car.BY JOSH LEVYJULY/AUGUST 2021 LOC.GOV/LCM15

16LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE

In 1960, John Steinbeck set out on amonthslong road trip to reacquainthimself with his country. He returnednot with clear answers but with hishead a “barrel of worms.” The Americahe saw was too intertwined with howhe felt in the moment, and with hisown Americanness, to permit an objectiveaccount of the journey. “External reality,” hewrote, “has a way of being not so externalafter all.”Pandemics aren’t the only reason Americanshave found sanctuary in our homes, or theonly anxious times we’ve itched to escapethem. The American road trip was firstpopularized during the auto camping crazeof the 1920s, with its devotion to freedomand communing with nature, but it wasdemocratized after World War II. The goldenage of the American family vacation cameduring the very height of the Cold War. It wasa time when, according to historian SusanRugh, the family car became a “home onthe road a cocoon of domestic space”in which families could feel safe to exploretheir country.The trips 20th-century Americans took,to national parks and resorts and historicsites, generated a wealth of traveloguesand other sources that often communicatefar more about the traveler than the roadtaken. They can help us understand ourown moment as well. Earlier this year, just29 percent of Americans felt comfortabletaking a commercial flight, but 84 percentwere comfortable using their own vehiclesfor a road trip. During the pandemic, tourismsuffered but road trips surged. Driving intothe great outdoors again felt like a safeescape.The Manuscript Division is full of roadtrip stories, not because it maintainsspecific road trip collections but becauseautomobile travel has been so centralto modern American life. Items in thedivision range from administrative recordsmapping out early guidebooks, to breathlessjournals recounting shared adventures,to testimonials of discrimination faced atroadside gas stations, restaurants andhotels. Together, they tell the story not ofone America, but of many.Researchers can find in the papers of theWorks Progress Administration the recordsof the American Guide Series, a Depressionera project to create richly texturedguidebooks of all of America’s states andmajor cities and some of its highways andwaterways. The series generated 378 booksand pamphlets altogether and employedsubsequently celebrated authors likeRichard Wright, Eudora Welty and Zora NealeHurston. Opposite: JournalistA.B. MacDonald puttogether this scrapbookof a road trip he tookin 1938 with daughterMary, who passedaway shortly after theirjourney. ManuscriptDivisionThe books were needed. Railroads, oneof the 19th century’s great symbols ofmodernity, had run along immovabletracks following set timetables. Richand poor travelers alike were essentiallyreduced to pieces of baggage. Earlyautomobiles promised a pathfindingfreedom, but motorists found America’sintercity roadways disjointed and virtuallyunmarked. Colossal early touring guideslike the Automobile Blue Book prescribedtedious turn-by-turn directions throughthe maze, but offered little insight into localcommunities.The WPA guides blended an attention tolocal history, culture and commerce witha literary sensibility. The project’s ambitionstill startles. An early prospectus promisedto advance efforts to “preserve nationalliteracy and historic shrines, to exploitscenic wonders and to develop naturaladvantages such as mines and quarries.”Steinbeck later called the guides “the mostcomprehensive account of the United Statesever got together.” Staffers, sometimesroad-tripping to fact check their work,labored to create a nuanced, encyclopedicaccount of what mattered about America —one mapped out in routes Americans coulddrive for themselves. Preceding pages: The Apollo theater in Harlem (fromleft); an Alabama Crimson Tide football game; the TidalBasin in Washington, D.C.; the beach at Atlantic City; ahome in Key West; the New York City skyline; and a foodstand at the Colorado state fair. Prints and PhotographsDivisionJULY/AUGUST 2021 LOC.GOV/LCM17

18LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE

Yet not all Americans traveled those routeswith the same ease. The records of theNAACP, held by the Manuscript Division,contain hundreds of testimonials speakingto the uncertainties and humiliations JimCrow-era African Americans faced whenthey ventured from home. For thesemotorists, the automobile’s promise offreedom coexisted with segregated busesand trains and a range of limitations on theirmobility. Black drivers experienced the openroad, according to historian Cotten Seiler,as “both democratic social space and racialminefield.” Automobiles seemed to offer areal escape from Jim Crow, but one thatalways lay just beyond the horizon.As a result, excursions often turned sour.One letter, submitted in 1947 by a high schoolscience teacher, details an afternoon roadtrip to a state park near Albany, “for thepurpose of sightseeing and enjoying thenatural beauty of the State of New York.”When a hotel bartender within the parktwice refused service to the teacher anda Jewish colleague, he insisted the hotelbe “made to pay” for his “humiliation anddamage to my pride.” Similar testimonials,of injustices on buses and trains and atroadside stops, illustrate the road trip’sunfulfilled promise for African Americantravelers. But they also suggest the allureof commanding one’s own vehicle and ofsidestepping more communal forms oftransit.Travelogues in collections of personal papersoffer another dimension still, documentingboth cosmopolitan tourism and nostalgicreturns home. A travel journal in thepapers of sociologist Rilma Oxley Buckmandescribes a footloose road trip from Indianato Alaska, taken in 1950 with a Purduecolleague in a late model Nash. The “ladycampers” had met in Yokohama just afterthe war, both working with the U.S. military.Adventuring their way north, they socializedand took snapshots. They noted the“Huckleberry Finn riverscapes” of Illinois andAlaskan roads “wobbly as a wagon trail.” Buttheir lives in Asia repeatedly intervened, frombirds that resembled Korean magpies tothe Japan-like hot springs of the CanadianRockies and then to worrying radio reportsabout the start of the Korean War.A scrapbook made by journalist A.B.MacDonald recounts a road trip with hisdaughter Mary in 1938, just four yearsbefore he died. From Kansas City to hisboyhood home in New Brunswick, fatherand daughter visit the old “homestead,”drink at a roadside spring where the familyonce watered their horses and catch upwith boyhood friends. Captions are writtentwo years later in a shaky hand, fromMacDonald’s sickbed. By that time, Maryhad tragically passed away. Above hisrecollections of an old schoolmate’s home,whose bed of nasturtiums both had admiredas a “perfect blanket of gold and crimson,”two flowers just received by mail arepressed into the paper. There, MacDonaldwrites, “Later — I did put two of the flowerson Mary’s grave, and there they remainedfor several weeks. She knew, of course shedid.” Opposite: In 1950,sociologist RilmaOxley Buckman anda colleague drove alate model Nash fromIndiana to Alaska andrecorded their journey inthis journal. ManuscriptDivisionAnd there are more. The Library’smanuscript collections show suffragistsembracing the automobile as a vehicle forwomen’s liberation and activists like SaraBard Field staging cross-country journeysto gain publicity for the cause. They showCarlos Montezuma, cofounder of the Societyof American Indians, defending the rightsof indigenous Americans to purchaseautomobiles without government permissionand to travel as they please. We even findpolitical satirist Art Buchwald in a comicallyoverloaded Chrysler Imperial, on a 1958 roadtrip from Paris to Moscow in order to testwhether such a drive can be made “withoutbeing arrested.”Road trips appear in unexpected places,and they can be revealing in unexpectedways. And in a nation knitted together withhighways, cars long ago became Americans’liberating, frustrating, memory-makinghomes on the road.—Josh Levy is a historian in theManuscript Division.JULY/AUGUST 2021 LOC.GOV/LCM19

AGAIN AND AGAINOver many miles and years,photographer Highsmith is takinga full-length portrait of America.BY MAR

Library of Congress Magazine. is issued bimonthly by the Office of . Communications of the Library of Congress and distributed free of charge to publicly supported libraries and research institutions, donors, academic libraries, learned societies and allied organizations in the United States