Transcription

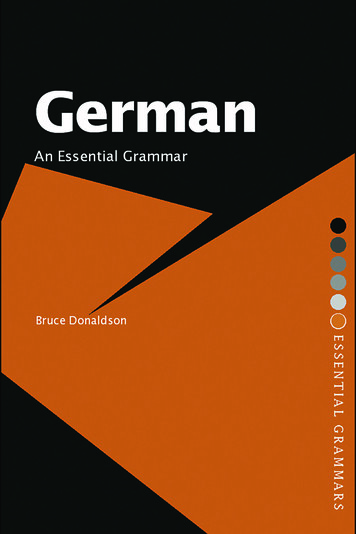

ContentsSerbianAn Essential GrammarSerbian: An Essential Grammar is an up to date and practical referenceguide to the most important aspects of Serbian as used by contemporarynative speakers of the language.This book presents an accessible description of the language, focusingon real, contemporary patterns of use. The Grammar aims to serve asa reference source for the learner and user of Serbian irrespective oflevel, by setting out the complexities of the language in short, readablesections.It is ideal for independent study or for students in schools, colleges,universities and all types of adult classes.Features of this Grammar include: use of Cyrillic and Latin script in plentiful examples throughouta cultural section on the language and its dialectsclear and detailed explanations of simple and complex grammaticalconceptsdetailed contents list and index for easy access to information.Lila Hammond has been teaching Serbian both in Serbia and the UKfor over twenty-five years and presently teaches at the Defence Schoolof Languages, Beaconsfield, UK.i

ContentsRoutledge Essential GrammarsEssential Grammars are available for the following languages:ChineseDanishDutchEnglishFinnishModern GreekModern nishSwedishThaiUrduOther titles of related interest published by Routledge:Colloquial CroatianColloquial Serbianii

ContentsSerbianAn Essential GrammarLila Hammondiii

First published 2005by Routledge2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RNSimultaneously published in the USA and Canadaby Routledge270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis GroupThis edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005.“To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’scollection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” 2005 Lila HammondTypeset in 10/12pt Sabonby Graphicraft Ltd, Hong KongPrinted and bound in Great Britainby MPG Books Ltd, BodminAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced orutilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, nowknown or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or inany information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writingfrom the publishers.British Library Cataloguing in Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryLibrary of Congress Cataloging in Publication DataHammond, Lila,Serbian : an essential grammar / Lila Hammond.p. cm. — (Routledge essential grammars)Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 0–415–28641–7 (pbk. : acid free) — ISBN 0–415–28640–9 (hardback : acid free)1. Serbian language—Textbooks for foreign speakers—English. 2. Serbian language—Grammar. I. Title. II. Series: Essential grammar.PG1239.5.E5H25 2005491.8′282421—dc222004010094ISBN 0–415–28640–9 (hbk)ISBN 0–415–28641–7 (pbk)

I dedicate this book toMilitca, Leo and Tara

Contentsvi

ContentsContentsPrefaceAcknowledgementsxiiixivPart I The language and its dialects1Chapter 1 Cultural, literary and linguistic background3Chapter 2 Dialects9Part II Alphabet, pronunciation and stress11Chapter 3 Alphabet13Chapter 4 Pronunciation174.14.2Consonants4.1.1Voiced and unvoiced consonants4.1.2Soft and hard consonants4.1.3Consonantal assimilations4.1.4Consonantal contractions4.1.5Fleeting a4.1.6Change of л/l to о4.1.7J changes4.1.8Effects of е/e and и/i on к/k, г/g andх/hVowels4.2.1Length and stress4.2.2Vowel mutationsChapter 5 Stress5.15.25.3Word stress and toneShift of stressSentence stress19192021222324252729292931313232vii

ContentsPart III Parts of speech33Chapter 6 Infinitives – classificationInfinitive and present tense stems6.2.1Type I conjugation6.2.2Type II conjugation6.2.3Type III conjugationTypes of verbs and aspects6.3.1Transitive and intransitive verbs6.3.2Imperfective and perfective verbsPresent tense6.4.1Formation of the present tense and itsuse6.4.2The negative present tense6.4.3The interrogative present6.4.4The negative interrogative present tensePast tense (perfect tense)6.5.1Formation of the perfect tense and itsuse6.5.2The negative perfect tense6.5.3The interrogative perfect tense6.5.4The negative interrogative perfect tenseFuture tense6.6.1Formation of the future tense and its use6.6.2The negative future6.6.3The interrogative future6.6.4The negative interrogative futureAorist tense6.7.1Formation of the aorist tense and its use6.7.2The negative aorist6.7.3The interrogative aorist6.7.4The negative interrogative aoristFuture II6.8.1Uses of future II6.8.2Formation of the future IIThe conditional6.9.1Uses of the conditional6.9.2Formation of the conditionalImperative6.10.1 Use of the imperative6.10.2 Formation of the imperativeReflexive verbsImpersonal 575768080818181828282838787889091

6.136.146.156.166.176.18Auxiliary verbsFormation of the interrogativeFormation of the negativePresent perfective aspect of бити/bitiИћи/izi and its derivativesModal verbsChapter 7 Nouns7.17.27.37.4Chapter 88.18.28.38.48.58.68.7Types of nounsGender of nounsCases of nouns7.3.1Nominative case7.3.2Genitive case7.3.3Dative case7.3.4Accusative case7.3.5Vocative case7.3.6Instrumental case7.3.7Locative caseDeclension of nouns7.4.1Masculine and neuter nouns7.4.2Feminine and masculine nouns ending in-a and the noun мати/mati7.4.3Feminine nouns ending in a consonant,in -o, -ост/ost or -ад/ad, and the nounкћи/kzi7.4.4Declension of irregular nounsPronounsPersonal pronouns8.1.1Declension of personal pronouns8.1.2Stressed personal pronouns8.1.3Unstressed personal pronouns8.1.4Order of unstressed personal pronounsReflexive pronounsPossessive pronounsDemonstrative pronounsRelative pronounsInterrogative pronounsUniversal pronounsChapter 9 Adjectives9.19.29.3Classification of adjectivesIndefinite adjectivesDefinite 188192195197199201203205207ix

Contents9.49.59.69.79.8Possessive adjectivesAdjectival declensionComparative adjectivesSuperlative adjectivesVerbal adjectives9.8.1The active past participle9.8.2Formation of the active past participle9.8.3The passive participle9.8.4Formation of the passive past participleChapter 10 Adverbs10.110.210.310.4Chapter 1111.111.211.311.4Substantival (nominal) adverbsAdjectival adverbsPronominal adverbsVerbal adverbs10.4.1 The present verbal adverb10.4.2 The past verbal adverbPrepositionsSimple prepositionsCompound prepositionsAccentuationPrepositions through the casesChapter 12 Conjunctions12.112.212.3Coordinating conjunctionsSubordinating conjunctionsDifferences in usages of што/eto and који/kojiChapter 13 Enclitics13.1Order and importance of encliticsChapter 14 Numerals14.1x14.214.314.414.514.614.7Cardinal numbers and their declension14.1.1 Number one14.1.2 Numerals two, three, four andthe numeral ‘both’14.1.3 Numerals five, six, seven and onwardsOrdinal numbers and their declensionFractions and decimal numbersCollective numeralsNumber 240243246249250255255258260263265267268269270270

tivesWeights and measuresAgeDays, months and datesTime14.13.1 Telling the time14.13.2 Time-related words and expressionsChapter 15 Quantifiers15.1Types of quantifiers15.1.1 Countable quantifiers15.1.2 Uncountable quantifiers15.1.3 Countable and uncountable quantifiersChapter 1616.116.216.316.416.5DeterminersPossessive determinersDemonstrative determinersIndefinite determinersInterrogative determinersNegative 288288289290291291Chapter 17 Particles, conjunctions and exclamations293Part IV Sentence elements and structure297Chapter 1829918.118.2SentencesElements of a sentenceTypes of clauses299301Chapter 19 Sentence structure30319.119.219.319.4Word orderPunctuationSimple sentencesComplex sentencesChapter 20 Word formation20.120.2PrefixesSuffixes20.2.1 Nouns20.2.2 308310310314316317xi

Contentsxii

ContentsPrefaceThe purpose of this book is to offer the English-speaking student ofSerbian a thorough and accessible overview of Serbian grammar.Serbian is a complex and expressive language and the scope of thisbook is too narrow to allow for sufficient examples to facilitate a moreprofound comprehension and understanding of the language. It doeshowever, strive to explain, as much as possible, the rules governingmost linguistic and grammatical conditions and structures.Serbian is not a language of simple constructions and straightforwardexpressions, and perhaps the most important piece of advice to thestudent would be to approach his or her study of this language with acurious and courageous mind.It is a beautiful language and I compliment the student wishing tolearn it.Lila HammondLondon, 2005xiii

ContentsAcknowledgementsI wish to express my gratitude to all the people who made writingthis book possible. Amongst them are Verica Stevanoviz, GordanaIliz, Miroslava Virijeviz, as well as Farret Abbas, Wayne Doran andZlata Krivokuza, who were always at hand with their support andencouragement.I also wish to thank my students, for their patience and perseverancein studying this language and in continually challenging me to improvemy methods of explaining and defining it. I thank them especially fortheir determination in pursuing their studies during those difficult times,of which there were, and inevitably are, many. Seeing them developinto users and speakers of Serbian has been a great inspiration andreward for me as a teacher.And finally, I wish to thank my editors, Sophie Oliver and JamesFolan for their patience, understanding, support and trust during thewriting of this book.xiv

Part ITheI language andPartitsThedialectslanguage and its dialectsCulturalbackground1

1Culturalbackground2

Chapter 1Cultural, literary andlinguistic backgroundCulturalbackgroundSerbian belongs to the Slavonic group of languages, which, along withthe Romance and Germanic languages, is one of the three largest groupsof the Indo-European family of languages.The Slavonic group of languages includes Polish, Czech and Slovak(belonging to the western group of Slavonic languages), Ukrainian,Belarus and Russian (belonging to the eastern group of Slavonic languages) and Slovenian, Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Bulgarian andMacedonian (belonging to the southern group of Slavonic languages).In the sixth and seventh centuries, various Slavonic tribes, some ofwhich were to become the Serbian nation, migrated from the north –Russia, Byelorussia and the Ukraine, where they shared the land withthe eastern Slavs – and travelled to the Balkan peninsula and the regionof Pannonia. At the time Bulgaria and the Byzantine Empire both wantedto occupy this region. The Slavs, themselves pagans, were also caughtbetween the Western, Catholic, and the Eastern, Orthodox religions. Inthe ninth century, Serbian rulers, struggling for power, converted toChristianity and were baptised by priests from the Byzantine Empire.Different tribes joined together under the common Christian religion.In the twelfth century, the founder of the most significant medievalSerbian dynasty, Stefan Nemanja, expanded his lands to include Kosovoand, further, to what is now the Montenegrin coast. Appointing hismiddle son, Stefan Nemanjiz, a son-in-law of the Byzantine imperialfamily, to replace him, Nemanja joined his youngest son, Sava, a monkin the Orthodox faith, to become a monk himself. Stefan Nemanjizmanaged, through clever running of the state, to fend off Serbia’senemies. He managed to maintain good relations with both the Westand the East and in the thirteenth century he received a royal crownfrom the Pope, which gave him the title of Stevan Prvovenaani, the‘first-crowned king’ of Serbia.His father, Stefan Nemanja, and brother, Sava, built the monastery ofHilandar on Mount Athos in Greece, which became the most prestigious3

1Culturalbackground4school for Serbian monks. This monastery is of great importance in thedevelopment of the Serbian church and Serbian culture.With the appointment of Sava (who was proclaimed a saint upon hisdeath) as archbishop in Nicaea, the centre for Greeks in Asia Minor,the links between the Serbian nation and the Orthodox tradition werefurther strengthened. On Sava’s instruction the Byzantine code of churchlaws and rules for use by the clergy, as well as many medical and scientific writings, were translated. He founded the first Serbian hospitals(in Hilandar and Studenica) and was the founder of Serbian literature,having written, with his brother Stefan Nemanjiz, the first originalSerbian literary work, the Vitae of St Simeon (The Life of StefanNemanja, their father and founder of the dynasty). (St Sava’s remainswere burnt by the Turks four centuries later in Belgrade, where thetemple of St Sava now stands.)Although Sava’s brother, Stefan Nemanjiz, had been crowned by thePope, he was under the influence of his brother and father and wantedto unify the Serbian state under the Orthodox religion. The Nemanjadynasty gradually succeeded in uniting all the Serbian lands and gaveto their country a strong and united church, the Serbian OrthodoxChurch. Culturally very active, the kingdom and church had their ownSlavonic liturgy and language (based on Old Slavonic). The translationof important Byzantine scrolls, liturgies, church laws, literary andarchitectural works was pursued and highly respected.The Nemanja dynasty continued to rule the state, and under the ruleof Stefan Duean (1331–1355), its boundaries expanded southward toinclude not only Macedonia and Albania, but regions of the ByzantineEmpire too. It covered the area from the Sava and Danube rivers downto the Gulf of Corinth, and became the leading power of the Balkanpeninsula. And as Duean elevated the Serbian archbishopric to the levelof a Patriarchate, he was crowned the ‘Emperor of the Serbs and Greeks’.Duean ruled the state and set up all the major state systems andjudiciary based on the Byzantine model. And since some of his territories were under the rule of custom and had never been under Byzantinelaw, he adopted an entire code of laws, under the name of DuEan’sCode, in an attempt to unify the territories and bridge the gap betweenthe impoverished and the wealthy.And, as had the rulers before him, Duean also emulated Byzantinearchitecture and art, and the many monasteries and churches built inthe Serbian state at the time are examples of a distinct Serbian Byzantine style in both these fields.The Serbs were eventually conquered by the Turks in the fifteenthcentury. An event in history that is taken to mark the fall of the greatSerbian Empire was the battle at Kosovo Polje in 1389. The lands weredivided between the Turkish warlords, who recognised each religious

group as an administratively separate community, even though, in manyways, the Serbian nation was placed under pressure to abide by Muslimsocial order. From the middle of the fifteenth century to the beginningof the nineteenth century, during the Ottoman rule, great migrations ofSerbs took place. Throughout this time, the Serbian Orthodox Churchdid much to give the Serbs a sense of unity and continuity. In two ofthe most important migrations that took place during this period thepeople were led by their patriarchs. When the Turkish governmentdissolved the Patriarchate of Pez in 1766, church authority was reestablished with the Greek archbishops, thus gaining an internationalposition. In 1832, the Serbian Church became autonomous. It did notunify into a Serbian Patriarchate until 1920 when the Serbs were unitedinto one state.After the elimination of the Patriarchate of Pez, the Turkish pashalicof Belgrade became the centre of Serbian culture and tradition. In 1804the Serbs there rebelled against the janissaries and Turkish landowners.Led by [or]e Petroviz, known as Kara]or]e, the rebels liberated thewhole pashalic.However, the war with the Turks continued, and in 1815 the newSerbian leader, Miloe Obrenoviz, signed a peace treaty with the Turksthat brought an end to the struggle against the Turks in that area. TheSerbs organised a state with a legal structure and a strong army, and,though still a client state of the Ottoman Empire, it had its autonomy.The state expanded to include territories already liberated byKara]or]e.While the Serbian people were fighting for an independent state from1835 to 1878, their rulers were aware that they needed a massiveaction plan in order to recover their people and culture from the backwardness caused by centuries of slavery under the Turks. By the endof the 1830s the principality had its own constitution, followed by aCivil Code as Prince Miloe laid down the foundations of democracyby distributing land to the peasants. State management, culture andeducation were institutionalised, and in 1882, elementary educationbecame obligatory. The Serbian Association of Scholars was foundedas well as the National Museum and the Academy of Arts and Sciences.The Great School, founded in 1863, became a university in 1905. Theeconomy and trade developed and the beginnings of industrialisationand banking also appeared. Talented people were sent to universitiesthroughout Europe, returning as knowledgeable and well-educatedEuropeans. This striving for scientific and scholarly advancement continued later in the Republic of Yugoslavia. Among the scholars of thesetimes was Nikola Tesla (the late nineteenth–early twentieth-centuryinventor in the field of electricity, a Serb originally from Croatia wholater moved to the United States), and other experts in their field.Culturalbackground5

1Culturalbackground6In 1918 the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was created.From 1929 it was called Yugoslavia.Yugoslavia emerged from the Second World War with a completelynew social structure. Led by the president of the state, Josip Broz Tito,it was initially a ‘people’s republic’ and then a ‘socialist republic’, consisting of six republics (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia,Montenegro and Macedonia) and two autonomous provinces, Vojvodinaand Kosovo. In the Yugoslavia prior to the war, the Serb, Croat andSlovene people were free to express and share their culture and faith.Postwar Yugoslavia saw a suppression of freedom in culture, also openexpression of religious practice was not looked upon favourably.Following Tito’s death in 1980 and under pressure from the autonomous provinces (particularly Kosovo, which sought to be grantedthe status of a republic) Yugoslavia began to disintegrate into its constituent republics. A bloody civil war broke out in 1991, and the countrywas divided into separate states, with many Serbs living outside Serbiaand Montenegro, the two states which remained together.The language of the Slavs who migrated to the Balkans in the sixthand seventh centuries also underwent changes. As the Slavonic tribesmigrated, the language of the southern Slavs changed from that spokenby the eastern Slavs. Though the languages remained essentially similar,the differences became distinctive when the south Slavs reached theBalkans and the Pannonia region, at which time some tribes travelledsoutheast, while others moved southwest. The differences in the interrogative pronoun ‘What?’ is a handy label for laying down the basicdifferences in what were to become the different languages and dialectsspoken in the region today. Those who travelled southwest used кај/kaj or ча/aa to say ‘What?’ Those Slavs travelling southeast used theinterrogative што-шта/eto-eta.When in the ninth century the Moravian ruler asked the ByzantineEmperor to send missionaries to convert the Slavs of the region to theChristian faith, the latter responded by sending the brothers Constantine(later called Cyril when he became a monk) and Methodius. They wereasked to translate, on the basis of their knowledge of the Slavoniclanguage spoken by a Macedonian tribe in the Salonika area, the mostimportant Byzantine religious books. The language had no written formand the brothers had to invent one. The language which they createdand translated into, Old Church Slavonic, was the first of the Slavoniclanguages to be used in literary and liturgical spheres.In order to translate the works, the brothers used the Greek alphabetas the basis on which they invented letters to represent the sounds ofthe Slavonic language. Glagolitic, the alphabet invented by Cyril, hadforty letters, a letter for each of the sounds. This alphabet was soonreplaced by the Cyrillic alphabet, consisting of the Greek alphabet of

the period with fourteen letters added. In cultural terms, the inventionof the alphabet was of great significance.Slavic monasteries on Athos were among the main centres of translation. Translation constantly developed and enriched the literary SerbianChurch Slavonic as many Slavic authors developed and practised theart of creating new words to express the abstract concepts they weretranslating into literary works.Church Slavonic, with its local variants, facilitated further dissemination of the Orthodox faith. The works translated from Greek werequickly shared by all the countries of the Orthodox Slavic world andthe languages of these countries, particularly Russian Church Slavonic,had a strong influence on Serbian Church Slavonic at the end of theeighteenth century.During the rule of Kara]or]e, many educated Serbs from Austriamoved into Serbia. Among them was Dositej Obradoviz, a great scholarwho spoke Latin, Greek, German, French, Italian and Russian. As soonas he heard of the liberation from the Turks, he returned to Serbia andmet with Kara]or]e. He believed that people had to be educated andenlightened. As Church Slavonic, which was interspersed with Russian,was too far removed from the living language of the people (most ofwhom were not able to understand the texts) Dositej wanted to bridgethe gap between this church language and the people’s language. Havingbeen exposed to the European Enlightenment, he insisted that the writtenlanguage be understood by everybody, including the uneducated. Soonthe Russian literary language was no longer used by Serbian authorsand Church Slavonic was used only in theological and liturgical books.Dositej became the minister of culture and fought to have schools builtand for both men and women to attend.The great Serbian philologist Vuk Karadfiz (1787–1864) played acrucial role in the development of the alphabet. He travelled aroundthe country, collecting folk stories and sayings, and incorporated thisspoken language into the written literary form. He attempted to createa completely phonetic alphabet, where one sound of the spoken languagewas represented by one symbol in the written form. With this in mind,he discarded some symbols he felt did not correspond to a particularsound, and introduced six new ones, in accordance with the principle,‘a letter for every sound’:2 1 ]ljnjzCulturalbackground df jIn 1818 he wrote the Serbian dictionary in the language spokenby the people. However, Karadfiz’s own language was of theIjekavian dialect, spoken in western Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina,7

1Culturalbackground8and Montenegro and among Serbs in Croatia and Dalmatia. The literary language until then was the Ekavian ktokavian dialect, spoken inthe northeastern regions, as that was where the most significant cultural,political and economic centres of the Serbs were located. The Serbsfrom these areas were not prepared to give up their Ekavian for anIjekavian dialect, and Serbia and Vojvodina retained their dialect. TheCroats and Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina, on the other hand, accepted his reforms completely, as did the Serbs living in Montenegro.In spite of these differences, Karadfiz’s reforms paved the way for aspontaneous development of the literary language through its relationship with the spoken word. The language expanded as new words werecreated from existing roots and nuances of meaning acquired. Wordsof Latin and Greek origin were adopted as the Serbian language becameincreasingly cosmopolitan. During the twentieth century, many Frenchand English words were also adopted.In the meantime, the Croats, who had during the fourteenth century,while under the influence of the western world and Catholicism, adoptedthe Latin alphabet, had in the nineteenth century, added letters forpalatal and palatalised consonants from Czech and Polish. Now thisalphabet, too, was phonetic (with the exception of lj, nj and df, wheretwo letters represent one sound).By the nineteenth century, realising that their languages had a lot incommon, the Croats and Serbs unified their languages under the nameof Serbo-Croatian. However, wanting secession from Yugoslavia, during the twentieth century, Croatian linguists began to emphasise thedifferences between the languages, proclaiming Croatian as a separatelanguage. New words were coined to prove that differences existed.With the break-up of Yugoslavia at the end of the twentieth centurycame the fragmentation of the unified language, Serbo-Croatian. TheCroatian language quickly developed as a separate language in relationto Serbian, with new words speedily introduced to mark its differences.Serbian, on the other hand, remained unchanged.

Chapter 2DialectsDialectsThree distinctive dialects are spoken in the various regions of formerYugoslavia. The dialects refer to the different ways the word ‘what’ isspoken:123кајкавски/kajkavski – the Kajkavian dialect – кај/kaj (what)This dialect is mostly spoken in Slavonia and northwestern Croatiaand near the Slovenian border where it closely resembles theSlovenian language.чакавски/aakavski – the gakavian dialect – ча/aa (what)This dialect is spoken in northern parts of Croatia and Istria, andalong the Adriatic coast and its islands.штокавски/etokavski – the ktokavian dialect – што/eto or шта/eta (what)This is the most widely spoken dialect in the region. It is spokenby all Serbs, Croats, Bosnians and Montenegrins, except in thoseregions already mentioned.The ktokavian dialect has three sub-dialects that developed from threedifferent pronunciations of the Old Slavonic jat, the long vowel b (distinct from the ordinary vowel e, which still exists as the e sound).The three sub-dialects are:123икавски/ikavski (Ikavian)Spoken in western Vojvodina, western Bosnia and Herzegovina,western Croatia and northwestern parts of the Adriatic.ијекавски/ijekavski (Ijekavian)Spoken in western Serbia, Croatia, Montenegro, the southernAdriatic coast and eastern Bosnia. The Croatian and Bosnian languages are of the Ijekavian dialect, written in the Latin alphabet.екавски/ekavski (Ekavian)Spoken in Serbia and Vojvodina, this is the dialect of the Serbianlanguage which generally uses the Cyrillic alphabet.9

2DialectsThe vowel b is pronounced as follows in each dialect:Ikavian – b/ivkbrjmlikomilkdhbvtvrimetimeIjekavian – je, b t/ijevkb trjmlijekomilkdhb tvt vrijeme timeEkavian – e/evktrjmlekomilkdhtvtvremetimeThe above differences in pronunciation apply only to words where theoriginal jat sound existed and not whenever the vowel e appears. Theword пет/pet (five), for example, is pronounced the same in all threesub-dialects.10

Part IIAlphabetAlphabet,pronunciationPartIandThe stresslanguage and its dialects11

3Alphabet12

Chapter 3AlphabetAlphabetThe Cyrillic alphabet, ћирилица/zirilica, and the Latin alphabet,латиница/latinica, are the two alphabets in use in Serbian. They bothcontain the same thirty letters, though not in the same order.The Cyrillic alphabet, ћирилица/zirilica, is based on Greek and wasadopted by the Serbs during the Byzantine era. The Latin alphabet,латиница/latinica, adopted by the Serbs living in the western parts ofthe country, in what was to become Croatia, in the fourteenth century,is the same as the one used in English, with the addition of five newletters and eight new sounds.13

3AlphabetThe Cyrillic alphabet:F DULÒT:PB RK VYÁJGHCNÙEA{WX„If,dul2t;pb rk1vy jghcn ea[wx iItalicsLatin equivalentF, f , ,D, dU, uL, lÒ, T, t:, ;P, pB, b , R, rK, k , 1V, vY, yÁ, J, jG, gH, hC, cN, nÙ, E, eA, a{, [W, wX, x„, I, iABVGD[ElZIJKLLjMNNjOPRSTyUFHCgDfkNote: There are two possible forms of Cyrillic u (the letter g) – one with a crossbar,one without. There are also two possible forms of Cyrillic l (the letter d) – one witha ‘tail’ going up: ,, and one with a ‘tail’ going down: optuberoomfutonHenrylotschocolatejuke-boxshoulder

AlphabetYfifj cfv gcf./Naeao sam psa.I found the dog.It is important that the cursive or hand-written Cyrillic form is learntproperly. The letters are distinctive in form, and each is connected toanother in an elaborate manner. Note the crossbar above Г (G), П (P),Т (T). A horizontal bar is often written under Ш (k) as well.15

3AlphabetThe Latin alphabet:Cyrillic ddf]efghijklljmnnjoprsetuvzfA WXÙL„ÒTAU{B RK npleasureNote: The hand-written forms of the Latin letters, with the addition of l f, [ ], yz, g a and k e, are the same as those used in English. The English letters q, w, xand y do not exist in the Serbian alphabet.

Chapter 4PronunciationEvery letter is pronounced.Consonants are pronounced similarly to English, with the followingexceptions:1The four consonants written as in English but with only one pronunciation as compared to several in English, are:w/c is never pronounced as in ‘carry’ but always

6.4.1 Formation of the present tense and its use 58 6.4.2 The negative present tense 63 6.4.3 The interrogative present 63 . book is too narrow to allow for sufficient examples to facilitate a more profound comprehension and understanding of the language. It does however, strive