Transcription

March 2007Series 1, Number 44An Introduction to theNational Nursing AssistantSurvey

Copyright informationAll material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may bereproduced or copied without permission; citation as to source, however, isappreciated.Suggested citationSquillace MR, Remsburg RE, Bercovitz A, Rosenoff E, Branden L. AnIntroduction to the National Nursing Assistant Survey. National Center for HealthStatistics. Vital Health Stat 1(44). 2007.Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataAn introduction to the National Nursing Assistant Survey.p. ; cm. -- (DHHS publication ; no. (PHS) 2007-1320) (Vital and healthstatistics. Ser. 1 ; no. 44)‘‘February 2007.’’Includes bibliographical references.ISBN-13: 978-0-8406-0614-3ISBN-10: 0-8406-0614-11. Nurses’ aides--United States. 2. Nursing homes--United States--Employees.3. Health surveys-- United States. I. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.)II. Series. III. Series: Vital and health statistics. Ser. 1, Programs and collectionprocedures ; no. 44.[DNLM: 1. National Nursing Assistant Survey (U.S.) 2. Nurses’ Aides-United States. 3. Nursing Homes--manpower--United States. 4. DataCollection--methods--United States. 5. Health Surveys--United States. 6.Research Design--United States. W2 A N148va no.44 2007]RT84.I58 2007614.4.’273--dc222006038116For sale by the U.S. Government Printing OfficeSuperintendent of DocumentsMail Stop: SSOPWashington, DC 20402-9328Printed on acid-free paper.

Series 1, Number 44An Introduction to theNational Nursing AssistantSurveyPrograms and Collection ProceduresU.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICESCenters for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for Health StatisticsHyattsville, MarylandMarch 2007DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 2007-1320

National Center for Health StatisticsEdward J. Sondik, Ph.D., DirectorJennifer H. Madans, Ph.D., Acting Co-Deputy DirectorMichael H. Sadagursky, Acting Co-Deputy DirectorJennifer H. Madans, Ph.D., Associate Director for ScienceJennifer H. Madans, Ph.D., Acting Associate Director forPlanning, Budget, and LegislationMichael H. Sadagursky, Associate Director forManagement and OperationsLawrence H. Cox, Ph.D., Associate Director for Researchand MethodologyMargot A. Palmer, Director for Information TechnologyMargot A. Palmer, Acting Director for Information ServicesLinda T. Bilheimer, Ph.D., Associate Director for Analysisand EpidemiologyCharles J. Rothwell, M.S., Director for Vital StatisticsJane E. Sisk, Ph.D., Director for Health Care StatisticsJane F. Gentleman, Ph.D., Director for Health InterviewStatisticsClifford L. Johnson, Director for Health and NutritionExamination SurveysDivision of Health Care StatisticsJane E. Sisk, Ph.D., DirectorRobin E. Remsburg, Ph.D., Deputy DirectorLauren Harris-Kojetin, Ph.D., Chief, Long-Term CareStatistics Branch

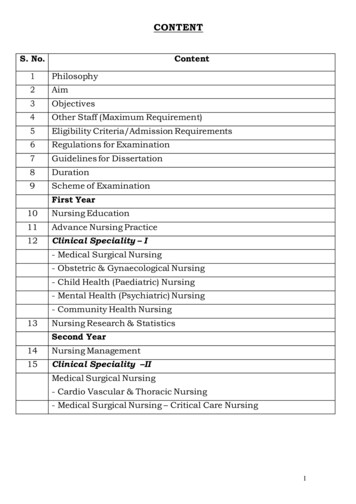

ContentsAcknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .ivIntroduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .The Demand for Nursing Assistants. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .The Move toward Enhancing the Direct Service Workforce. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Report Organization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1233Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Research Goal and Objectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Participant Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Sample Design and Selection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Response Rate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Instrumentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Pilot Test . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Procedures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33445567Combining Establishment and Worker Surveys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10Advantages of Combining Establishment and Worker Surveys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10Expanded 2004 National Nursing Home Survey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Uses of Survey Data and Data Publication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Potential Uses of the National Nursing Assistant Survey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Potential Uses of the NNAS Data Linked with the NNHS and Other Data Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Data Publication and Availability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15Summary and Future Directions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15AppendixesI.II.Promotional and Contact Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19List of Survey Items . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27Text TablesA.B.C.D.E.F.National Nursing Assistant Survey Response Rate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5Key subject areas on the National Nursing Assistant Survey questionnaire . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6Contents of advance packets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8Important policy and practice issues associated with paraprofessional workers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Examples of research questions that may be addressed by the National Nursing Assistant Survey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Potential analyses of the National Nursing Assistant Survey with the National Nursing Home Survey and other datasources. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13iii

AcknowledgmentsThe National Nursing AssistantSurvey (NNAS) was sponsored andfunded by the Office of the AssistantSecretary for Planning and Evaluation(ASPE).The survey was conducted by theCenters for Disease Control andPrevention’s National Center for HealthStatistics. The project director wasRobin Remsburg. Design, production,and analysis assistance for this projectwas provided by Abigail Moss,Genevieve Strahan, Alvin Sirrocco,Sarah Gousen, and Iris Shimizu.The interview was developed withthe assistance of Mathematica PolicyResearch, Inc. Westat and theirsubcontractors conducted all interviewsfor the project.We gratefully acknowledge thecontributions of Andreas Frank,previously with ASPE, and WilliamMarton of ASPE. We are indebted toour national advisory group memberswho were most giving of their time andexpertise: Marilyn Biviano, BarbaraBowers, Joseph DuBois, the late SusanEaton, William Eschenbacher, MaryHarahan, Mark Hatch, Graham Kalton,Peter Kemper, D.E.B. Potter, EdwardSalsberg, Anita Schill, Robin Remsburg,Robyn Stone, and David Zimmerman.iv

ObjectivesThis report provides an introductionand overview of the National NursingAssistant Survey (NNAS), the firstnational probability survey of nursingassistants working in nursing homes.The NNAS was designed to providenational estimates and to allow forseparate estimates to be calculated fornursing assistants by geographiclocation of the agency and for workersby tenure at the sampled facility.This report includes a description ofrelevant research that led to federalinterest in sponsoring the NNAS, typesof data collected, methodology, linkagebetween the NNAS and the 2004National Nursing Home Survey (NNHS),advantages of combining establishmentand worker surveys, and potential usesof the data.MethodsThe NNAS was conducted as asupplement to the 2004 National NursingHome Survey. The design was a stratified,multistage probability survey. Nursingfacilities were sampled and then nursingassistants were sampled within thefacilities. Telephone interviews wereconducted with nursing assistants usingComputer-Assisted Telephone Interviews(CATI). The survey instrument consisted ofsections on recruitment, training andlicensure, job history, family life,management and supervision, clientrelations, organizational commitment andjob satisfaction, workplace environment,work-related injuries, and demographics.Results and ConclusionsA total of 3,017 interviews werecompleted from September 2004 toFebruary 2005. The overall responserate was 53.4 percent. A public-usedata file has been released thatcontains the interview responses andsampling weights. The file also includesownership, bed size, and geographiclocation of the facility where the nursingassistant was sampled. Estimatesbased on the sampling weights can beused to produce national estimates.Keywords: National NursingAssistant Survey c National NursingHome Survey c nursing assistant cjob satisfaction c turnoverAn Introduction to the NationalNursing Assistant SurveyBy Marie R. Squillace, Ph.D., Department of Health and HumanServices, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning andEvaluation; Robin E. Remsburg, Ph.D., and Anita Bercovitz, Ph.D.,National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health CareStatistics; and Emily Rosenoff, M.P.A., Department of Health andHuman Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning andEvaluation; and Laura Branden, WestatIntroductionSince the 1990s, the Office of theAssistant Secretary for Planningand Evaluation (ASPE), the U.S.Department of Health and HumanServices (HHS), has made the long-termcare workforce a major focal point of itspolicy research agenda. The largest andmost visible of its research initiatives inthis area is the National NursingAssistant Survey (NNAS), the firstnational probability sample survey ofnursing assistants employed in nursinghomes. The NNAS was designed toprovide an evidence base forunderstanding what draws individuals tocareers as nursing assistants and to workin nursing homes, and what contributesto their satisfaction and likelihood ofstaying in their jobs. This reportprovides a historical perspective on thefederal government’s involvement increating the NNAS as an example of thefederal role in enhancing the availabilityand capabilities of the direct serviceworkforce. Specifically, this reportdescribes relevant research that led tofederal interest in sponsoring thissurvey; introduces the NNAS, includingthe types of data collected, the methodsundertaken, including the linkagebetween the NNAS and the 2004National Nursing Home Survey(NNHS); the advantages of combiningestablishment and worker surveys andthe potential uses of these data; andhighlights the expanded and improvedNNHS.The immediate antecedents of theNNAS can be found in Senate Report107–84, Departments of Labor (DOL),Health and Human Services, andEducation, and Related AgenciesAppropriation Bill. In fiscal year 2002,Congress requested that the Secretariesof Health and Human Services andLabor identify the causes of labor forceimbalances among frontline caregivers,including registered and licensedpractical nurses, certified nurse aides,and other direct care workers inlong-term care settings such as nursinghomes, assisted living, and home healthcare. In addition, Congress requestedthat HHS and DOL makecomprehensive recommendations to theHouse and Senate AppropriationsCommittee to address the increasingdemand of an aging population (1).The report, The Future Supply ofLong-Term Care Workers in Relation tothe Aging Baby Boom Generation:Report to Congress, is a collaborationbetween HHS and DOL in response tothe requests from the U.S. Congress.One recommendation from this reportwas to support research activities toinform policymakers at all levels ofgovernment on the quality andavailability of the long-term careworkforce, including such issues aswage and benefit trends among frontlinecaregivers, understanding the effect oftraining and workplace culture onPage 1

Page 2 [ Series 1, No. 44worker retention, and understanding howworker characteristics relate torecruitment and job satisfaction (2).Although widely used in the researchand policy literature, the concepts ofrecruitment and retention have not beenmeasured in consistent ways, making itdifficult to compare the effects ofinterventions designed to improveretention (3).In 2003, ASPE contracted with anindependent research organization todevelop a series of design options for anational survey of paraprofessionalworkers in institutional and communitybased settings. As work progressed,ASPE decided to fund one of theemerging design options, a NationalSurvey of Certified Nursing Assistantsin Nursing Homes. The objectives of thesurvey were to describe nursingassistants’ work experiences and reasonsfor entering the field; to find out whatchanges in working conditions, wages,benefits, and career growth for nursingassistants would make the job moreattractive; and to provide a betterunderstanding of why nursing assistantsleave the field. The survey of nursingassistants was fielded as a supplement tothe 2004 NNHS at a subsample ofnursing homes participating in theNNHS. Ultimately, survey results willstrengthen federal, state, and providerefforts aimed at recruiting a qualifiedand committed workforce. ASPE is thesponsor of the NNAS; its design andimplementation were made possiblethrough collaborations with twoindependent research organizations, anational advisory group, privateconsultants, and a sustained partnershipwith the Centers for Disease Controland Prevention (CDC), National Centerfor Health Statistics (NCHS).The Demand for NursingAssistantsThe total number of Americans inneed of long-term care is projected tomore than double from 13 million in2000 to 27 million in 2050 (2).Long-term care providers facetremendous challenges each day tryingto provide high-quality care to clients.One of the greatest challenges is staffretention among direct care workers—nursing assistants, personal careattendants, and home health aides—whoprovide hands-on services to clients.These frontline caregivers provide themajority of paid assistance to personswith disabilities (of all ages) in theformal long-term care delivery system(4). Nursing assistants working innursing facilities make up an estimated24.7 percent (593,490) of the over 2.4million paraprofessional workers (5,6).Since nursing assistants primarilyprovide hands-on assistance to clientswith activities of daily living (ADLs),they are key players in determining thequality of paid long-term care.Turnover among direct care workersis high and can reach rates of over100 percent in some organizations,although the definition of turnover mayaffect the rate calculation by as much as47 percent (7–10). The nursing homeindustry, in particular, has been plaguedfor decades by an inability to recruit andretain nursing assistants (7,11).Long-term care providers are reportingnational average nursing assistantturnover rates at 71 percent and morethan 52,000 vacant nursing assistantpositions (12). Gaps in staffing maydisrupt the continuity of patient care (7),worker morale (13), worker safety (14),and quality of care (15–22).Turnover of direct care workers hasother repercussions as well: it is costlyto the provider and to the payer (13,19,23–26). Both direct costs (recruiting,training new employees, and hiringtemporary staff) and indirect costs(reduced productivity, deterioration inorganizational culture, and morale)associated with turnover cancompromise the quality and continuityof clients’ care (13,23). Further, costsfor recruiting and training new directcare workers may be reflected in thedemand for higher governmentreimbursement rates to maintainadequate care quality.Turnover and high vacancy rates ofdirect care workers have implicationsfor family caregivers as well. Theinability to recruit and retain direct careworkers places more pressure oninformal (unpaid) family caregivers toprovide care and exacerbates thechallenge of arranging for formal care(27).While the significance of the directcare worker’s role in the provision oflong-term care has become morerecognized by long-term careprofessionals and researchers, theseworkers experience stressful workingconditions, little career mobility, and areamong the lowest-paid workers in thehealth care field (4,21,24,28,29).Long-term care organizations, therefore,face considerable difficulty in recruitingand retaining direct care staff. As thedemographics shift toward a largeraging population and greater demand fordirect care workers, the recruitment andretention problem is likely to intensify.If left unaddressed, this emerging caregap could severely restrict the ability ofproviders to deliver adequate long-termcare (30,31).The ability to understand andreplicate programs that reduce turnovercan improve continuity of care whilereducing the need for higher levels ofreimbursement, yet evidence on whatlong-term care organizations and federal,state, and local policymakers can do toreduce job turnover is quite limited.While wage and benefit increases havebeen deemed as possible solutions to thedirect care worker turnover problem(32), impending Medicaid cuts renderthese solutions unlikely (33) and suggestthe need for alternative solutions such aspeer mentoring, career ladders, enhancedstaff-family communication, alternativelabor pools, multi-faceted initiatives(public awareness campaigns, careerenhancements, quality improvementinitiatives), and culture and managerialchanges. These are the primarystrategies currently being employed byproviders and states (34–38). Moreover,supporting data to demonstrate theefficacy of the wage pass-through as a

Series 1, No. 44 [ Page 3tool to reduce worker vacancies andturnover are lacking. A study of 12states that had implemented wagepass-through programs found that threeprograms had no impact on recruitmentand retention; three could not determinewhether there was any measurableeffect; and four either had a positiveimpact or ‘‘probably had some positiveimpact’’ (39).Adequate wage and benefit levelsare important in recruiting and retainingcommitted and high-quality workers fordirect care jobs (40); however, increasedbenefits cannot solely resolverecruitment and retention problems (32).Studies have shown that factors otherthan wages and benefits can have animpact on intent to stay on the job andworker satisfaction (36,37).Employees’ attitudes about variousaspects of their jobs, for example, affecttheir overall job satisfaction, theircommitment, and the likelihood thatthey will remain with their employer(41–43). Survey research can reveal themost important drivers that positively ornegatively impact job satisfaction,thereby informing targeted retentionefforts in areas of supervision, skilldevelopment, or advancementopportunities (44). While the U.S.Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)provides employment estimates tomonitor the labor force, no nationallydescriptive information is collecteddirectly from the paraprofessionalworkforce to evaluate what motivatesindividuals to choose careers as directcare workers in long-term care settings,and what contributes to the likelihoodthat they will continue in these positionsbased on their job satisfaction,environment, training, and advancementopportunities. Studies have collectedsuch data from these workers, but theyare state or community specific (45–49)or focused on a specific segment of theworkforce, such as older workers (50).The Move towardEnhancing the DirectService WorkforceWith widespread current shortagesthat are likely to increase as the demandincreases, industry and policy leadersrecognize the urgency that direct serviceworkforce development plays forstaffing the continuum of care outlinedin the President’s New FreedomInitiative (51–53). The goal of providingconsumers with choices that maximizetheir independence can only occur ifthere are enough capable caregivers toprovide such services. The DOLprojections continue to list these jobsamong those with the highest growthrate. The number of nursing assistants,orderlies, and attendants are expected toincrease by 22.3 percent (from 1.455million to 1.781 million); the number ofpersonal and home care aides isexpected to grow by 41 percent (from701,000 to 988,000); and the number ofhome health aides is expected to growby 56 percent (from 624,000 to 974,000)between 2004–14 (6). The communitybased approaches that are supported bythe New Freedom Initiative requiremany more direct services workers thanare currently in the field. It is, therefore,critical that industry and policy leadershave access to information that is usefulin improving the attractiveness ofcare-giving jobs and in reducingturnover. The NNAS provides aframework for future evidence-basedpolicy, practice, and applied researchinitiatives to address the long-term caredirect care workforce shortage.Report OrganizationThe remainder of this reportincludes the following sections: Methodology—including study goalsand objectives, participantinclusion/exclusion criteria, anoverview of the study sample andresponse rate, and detailed sectionson instrumentation, procedures, andstudy limitations. Combining establishment andworker surveys—including anoverview of the expanded NNHSand advantages of combiningestablishment and worker surveys. Uses of survey data andpublication—including uses of theNNAS and the NNAS linked to theNNHS and other data sources, andguidelines for data access. Summary and future directions—including key issues and next steps.MethodologyResearch Goal andObjectivesThe goal of the study is to provideindustry and policy leaders withinformation that is useful for improvingthe attractiveness of long-termparaprofessional care-giving jobs and inreducing turnover. In addition, the studysought to: Describe nursing assistants’ workexperience and reasons for enteringthe field. Determine what changes in workingconditions, wages, benefits, andcareer growth will make nursingassistants’ jobs more attractive. Provide a better understanding ofwhy nursing assistants leave thefield. Provide a framework for futureevidenced-based policy, practice,and applied research initiatives toaddress the long-term direct careworkforce shortage.The survey was conducted as asupplement to the 2004 NNHS. The2004 NNHS is part of a continuingseries of nationally representativesample surveys of United States nursinghomes, their services, their staff, andtheir residents. The NNHS was firstconducted in 1973–74 and repeated in1977, 1985, 1995, 1997, 1999, and mostrecently in 2004. Although each surveyhas emphasized different topics, they allprovide basic information about nursinghomes, the services they provide, theirstaff, and their residents. The nursinghome survey was preceded by a seriesof surveys from 1963 through 1969called the Resident Places Surveys.Data for the NNHS are collectedvia on-site interviews withadministrators and staff who are familiarwith sampled residents and use facilityand medical records to respond to thesurvey. For the NNAS, nursingassistants were sampled from a subset of

Page 4 [ Series 1, No. 44nursing homes participating in theNNHS.Participant Inclusion andExclusion CriteriaThe target population for the NNASis nursing assistants who work innursing homes and assist residents withADLs, including eating, transferring,toileting, dressing, and bathing. Thenursing assistants must be certified bythe state to provide Medicare orMedicaid reimbursable services.Certification, required by the OmnibusBudget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of1987 (P.L. 100–203) (54), mandates thatnursing assistants complete 75 hours oftraining and a written certification test.This study includes nursing assistantscurrently in the process of certificationand those who started working as anurse aide prior to 1987, when thecertification process was implemented.Participants must be an employee ofthe nursing home either full or parttime, work at least 16 hours per week,and must be paid to provide ADLassistance. The survey instrument wastranslated into Spanish for nursingassistants who were unable to participatein English.The NNAS specifically excludesnursing assistants who are not certified(unless they are currently in the processof certification or started working as anurse aide prior to 1987 when thecertification process was implemented),are employed through contractualarrangements, and only provideassistance with instrumental ADLs—such as transportation, shopping,housekeeping, meal preparation, ormedication administration. Nursingassistants who did not speak English orSpanish were excluded becauseproviding interpretive services for otherlanguages was cost prohibitive. Nursingassistants who worked less than 16hours per week were excluded from thesurvey to ensure that respondents wouldhave had enough exposure andexperience in the nursing home toaccurately report on organizationalculture and work policies. In addition,since the NNAS sample was selectedfrom facilities participating in theNNHS, any workers in facilitiesexcluded from the NNHS were in turnexcluded from the NNAS (those withfewer than three beds, not certified byMedicare or Medicaid, or did not have astate license to operate as a nursinghome).Although the NNAS was designedto allow for a better understanding oforganizational culture and how it relatesto worker satisfaction, it is known thatmany nursing assistants hold downmultiple jobs and may actually work inseveral nursing homes. To avoidpotential confusion, contract workersand nursing assistants who worked lessthan 16 hours per week were excludedfrom the survey to ensure thatrespondents would have had enoughexposure and experience in the nursinghome to accurately report onorganizational culture and work policies.Contract workers and those employedfewer than 16 hours per week may havedifferent needs and work challengesthan full-time employees. Moreover,facilities with a high percentage of theseemployees are likely to have a differentwork environment and organizationalculture than those with fewer contractand part-time employees.Only certified nursing assistantsproviding help with ADLs were eligiblefor the survey. Certified nursingassistants working in other roles—suchas medication aides, or activitycoordinators, and other noncertifieddirect care workers providing ADLassistance (such as feeding assistants)were ineligible for the survey.Undoubtedly, these workers face similarwork challenges, yet the range of theirworkload, duties, and responsibilities arefundamentally different than certifiednursing assistants delivering help withADLs.Sample Design andSelectionThe sample design for the nursingassistant survey was developed with theprimary goal of preparing nationallyrepresentative and reliable estimates ofnursing assistants. As such, the NNASinvolved a stratified, multistageprobability design in which nursingfacilities were sampled and then nursingassistants were sampled within thefacilities. The sample design allows forseparate estimates to be calculated forworkers by the Core Based StatisticalArea (CBSA) geographical location ofthe nursing facility (metropolitan,micropolitan, or neither), and forworkers by tenure at the sampledfacility (less than 1 year working at thesampled facility or more than or equalto 1 year working at the sampledfacility).Sampling Frame for Selectionof Nursing HomesFor the 2004 NNHS, 1,500 nursingfacilities were selected from a samplingframe of nursing homes in the UnitedStates. The sampling frame for theNNHS was drawn from two sources: theCenters for Medicare and MedicaidServices (CMS) Provider

Keywords: National Nursing Assistant Survey c National Nursing Home Survey c nursing assistant c job satisfaction c turnover An Introduction to the National Nursing Assistant Survey By Marie R. Squillace,