Transcription

PermacultureRoslynn Brain & Blake ThomasDepartment of Environment & SocietyWhat is Permaculture?Permaculture is a design concept for sustainable, foodproducing landscapes mimicking the diversity and resilienceof natural ecosystems. Although concepts included inpermaculture design have been in practice for millenia byvarious cultures worldwide, the term “permaculture” as itis currently understood was first coined in Tasmania by BillMollison and David Holmgren in the mid-1970’s (Nabhan,2013). Mollison and Holmgren described permacultureas, “an integrated, evolving system of perennial or selfperpetuating plant and animal species useful to man” (Mollison& Holmgren, 1978). The use of the word, and scope of thedefinition, has varied greatly since the 1970’s; much like theuse of ‘sustainability’ and ‘ecology’. Holmgren later expandedthe definition to, “consciously designed landscapes whichmimic the patterns and relationships found in nature, whileyielding an abundance of food, fibre and energy for provisionof local needs” (Holmgren, 2003). Additional definitionsfrom members of the permaculture community include: Permaculture is the conscious design and maintenanceof agriculturally productive systems which have thediversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems. Itis the harmonious integration of the landscape with peopleproviding their food, energy, shelter and other material andnon-material needs in a sustainable way (Bell, 2005).Permaculture:A design process mimicking natural ecosystems.Version: December 2013Texts about permaculture design abound. Popular beginners texts includePermaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability and Gaia’s Garden. Permaculture is a set of techniques and principles for designingsustainable human settlements though permaculture practitionersdesign with plants, animals, buildings and organizations, they focusless on those objects themselves than on the careful design ofrelationships among them – interconnections – that will createa healthy, sustainable whole (Hemenway, 2001). A permaculture system is a system that resembles nature andis based on natural cycles and ecosystems (Holzer, 2004).From the above definitions, it can be seen that permaculturedesign has evolved beyond food systems to encompass thebroader landscape of architecture and human relationships. JoelGlanzberg, regenerative design and ecological restoration expert,emphasized “it is a holistic design approach for all human needsthat works on creating change by shifting underlying patterns”(Glanzberg, 2013). A holistic design approach demands a shift inconventional, mechanistic thinking. The theoretical foundationsof permaculture will help shed light on this way of thinking.sustainability/2013/17pr1

Another factor that would encourage a group or anindividual to adopt permaculture practices would bea worldview that included a developed sense of place.If people feel connected to their community andenvironment, they would be more likely to embracepermaculture. Humans can develop a sense of place byobserving patterns, processes, and cycles within nature.Humans must reconnect their aspirations and activitieswith the evolution of natural systems, regenerating asopposed to degenerating our landscapes (Glanzberg, 2013;Mang & Reed, 2012).Participants in USU Extension’s Permaculture Workshop observethe surrounding environment interacting with the campus’s futurepermaculture garden site. This includes the watershed, wind strengthand direction, seasons, sun cycle and more.Permaculture TheoryBefore breaking soil and designing structures, permaculturepractitioners first observe patterns and characteristics ofthe environment at the chosen site. This includes visitingthe site at various times of the day, during various seasonsand weather conditions, and observing the landscape fromdifferent viewpoints. Following is an elaboration of the theorybehind permaculture design.Worldview and PlaceObservation of our surroundings is often the firstprinciple presented in permaculture literature (Holmgren,2007, McManus, 2010, Bane, 2012). How we perceive, orobserve, our environment is influenced by our worldview.In other words, the roots of our worldview influence manyof our attitudes and perceptions toward the environment.Because permaculture is a holistic design approach witha concern for the health of the environment, a group oran individual will be more likely to adopt permacultureprinciples if they have an environmental worldview.Tracing thinking further ‘upstream’, from our worldview,to our experiences that formed that view, can enrich thedialogue taking place among advocates for sustainablybuilt environments (Mang & Reed, 2012). Ecologicalproblems and designs have been traditionally addressedthrough mechanical means (Berry, 1981). For example,designing factory-style farming facilities via mechanicalorder. streamlines efficiency in producing a single product.However, it also creates dependency on inputs, unusedwaste, minimizes biological exchange and increasesvulnerability in the wake of ecological disturbance.Biological solutions to problems are often overlookeddue to a worldview with a mechanical preference. Thispreference for man-made, mechanical solutions is notconducive to the adoption of permaculture theory.2“Sustainability”As world population and resource consumption continueto follow an upward trend, the importance of humansreconnecting with natural systems increases. Problemsolving, conflict resolution, and increased stewardship arerequired for world populations to continue - or sustain.Oftentimes, sustainability is defined as using less, or usingup capital more slowly. That definition creates an illusionof achievability, and leaves out the most integral elementsof the human race’s ability to sustain itself. Sustainability isvalue laden, and achieving sustainability requires problemsolving (Tainter, 2003). Permaculture integrates thehuman value aspect by approaching problems throughecology, systems thinking, and holistic inquiry. Ethicsand considerations ingrained within those overarchingapproaches, taken from Holmgren (2007) include: Land and nature stewardship The built environment Tools and technology Culture and education Health and spiritual well-being Finances and economicsDesigning a permaculture site at USU following an observation of thebiological and social patterns interacting with the site.

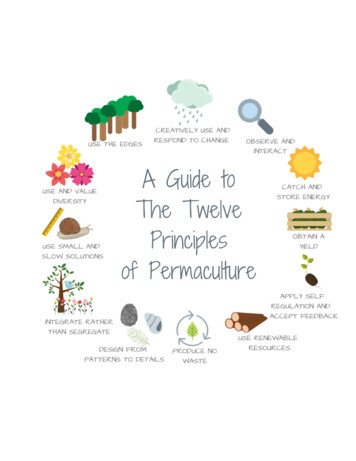

Permaculture PrinciplesPermaculture literature often contains listed principles. Most ofthe principles have core similarities among various authors andexperts. Listed below are twelve principles adapted from DaveHolmgren (Holmgren, 2007). Holmgren’s list encompassesall essential elements of permaculture. The twelve ethics andprinciples follow:Design from Patterns to DetailsObserve and InteractIntegrate Rather than SegregateDesign should consider different seasons, times of day, andcultures. Ways to work and design with existing patterns innature should be considered.This requires the recognition of complex connections innature, and making beneficial use of those interactions.We must brainstorm the many functions that each elementcan perform.Catch and Store EnergyBy stepping back, we can observe patterns in nature andsociety. These can form the backbone of our designs, withthe details filled in as we go (McManus, 2010). Thoughtfuldesign is a way of addressing and solving many of ourproblems at the source.Renewable ways of capturing and utilizing energy should bea priority. Energy, which gives us the ability to work, shouldnever be wasted. True costs (i.e. negative externalities, humanwelfare, habitat protection, etc.) should be a central part ofenergy dialogue. Infrastructure improvements, retrofitting,passive design, and alternative storage techniques should beprioritized.Use Small and Slow SolutionsObtain a YieldUse and Value DiversityDesign should focus on principles of self-reliance. Producingan agricultural yield is necessary for independence andcontinuity. Yields are encouraging, and they create ‘positivefeedback loops’ (Holmgren, 2007).Diversity fosters resilience. A society rooted in monocultureis vulnerable to unexpected change. Permaculture seeksto understand past, present, and potential biological andcultural diversity.Apply Self-Regulation and Accept FeedbackUse Edges and Value the MarginalWith better understanding of how positive and negativefeedbacks work in nature, systems can be designed that aremore self-regulating, thus reducing the work involved inrepeated and harsh corrective management (Holmgren, 2007).A point where two systems meet is often a place whereproductivity and stability can be found. Rather thandisregarding the marginal, we should look for ways tomake use of its diversity and productivity.Use and Value Renewable Resources andServicesCreatively Use and Respond to ChangeWe live as a result of the ability of the living world to regenerate(Glanzberg, 2013). A diversified use of renewable resources, atan appropriate level of use, can help us limit our consumption.Smaller systems are easier to maintain than big ones, makingbetter use of local resources and producing more sustainableoutcomes (McManus, 2010). Also, be sure to take adequatetime through observation and seeking local knowledge infinding solutions.We can have a positive impact on inevitable change bycarefully observing, and then intervening at the right time(McManus, 2010). We must not seek to take away the selfdetermination of land in the process.Produce No WasteLook for ways to make waste a useful input in our system,rather than just an output. Recycling, composting, and reducingwaste are increasingly important as population increases.3

Permaculture in PracticeStack FunctionsIf you are interested in incorporating permaculturedesign concepts into your own landscape, the followinglist of examples can serve as a basis for brainstorming.Stacking functions, or companion planting, is a great way to reduceyour external inputs. What this means is to consider the entirespectrum of benefits any plant can provide, and also to considerwhat that plant needs to thrive. Do the same for several plantsand determine whether any one plant can meet the nutritional orstructural needs of another, when interplanted closely together.Harvest RainwaterA basic start to harvesting rainwater is to build or purchase acatchment system, such as a barrel attached to your householdeaves trough runoff point (See www.water.utah.gov for furtherinformation on water harvesting laws for Utah). However, tomaximize use of your catchment system, design your landscapein a manner that naturally harvests rainwater as well. Thisincludes building infiltration basins, also known as swales(indented gardens), as opposed to mounds (elevated gardens).Swales can be connected to runoff points in your landscape tomaximize natural rainwater harvesting. An advanced conceptof this is to build a diversion swale. According to BradLancaster (2013; p.73), “a diversion swale is built slightly offcontour, allowing a portion of the water to soak into the soillocally while moving surplus water slowly downhill from oneplace to another, infiltrating water all along the way.” Thishelps slow water flow, decreases water inputs and associatedcosts, and prevents erosion.A great example of stacking functions can be taken from theNative American tradition of a Three Sisters Garden of corn,beans and squash. Corn provides a natural pole for beans,beans fix nitrogen in the soil that other plants use, and squashprovides a natural ground cover to reduce weeds, retain soilmoisture, to serve as a natural mulch, and the prickly hairs helpdeter pests. The result is known as “overyielding,” where thecombined yield of all three crops grown together on the sameland is generally higher than what any one of the crops couldproduce in the same area of land if planted alone (Nabhan,2013). Lastly, the three sisters also nutritionally complementeach other. Beans are rich in protein, balancing a lack of neededamino acids found in corn; corn provides carbohydrates; andsquash yields vitamins from the fruit and oil from the seeds.Rainwater Harvesting Formula:To calculate the amount of rainwater you could harvest on yourown rooftop and/or landscape, consider the following formula:CATCHMENT AREA (in square feet) x AVERAGE ANNUALRAINFALL (in feet) TOTAL RAINWATER FALLING ONTHAT CATCHMENT IN AN AVERAGE YEAR (in cubic feet).If your annual rainfall is measured in inches, divide inches of rainby 12 to get annual rainfall in feet (Lancaster, 2013).A Three Sisters Garden at the UMass Amherst Campus, Massachussetts - partof the University’s Permaculture Initiative (www.UMassPermaculture.com)Design a Plant GuildGarden basins/swales form a living sponge of mulch and vegetation.Basins are designed to infiltrate water quickly so there are no problems withmosquitoes or anaerobic soils. These basins, with their spongy mulch andsoil-burrowing plant roots, infiltrate all water within 20 minutes ( RainwaterHarvesting for Drylands and Beyond; www.harvestingrainwater.com)4A plant guild draws concepts of design from forest ecosystems.Begin with a canopy layer, such as large fruit and/or nut trees.Under this layer, plant dwarf fruit trees. As highlighted by GaryNabhan (2013, p. 132), “A dwarf fruit tree may sequester as muchas 28 pounds of CO2 a year, while a larger semi-dwarf or full-sizedtree will sequester between 220 and 260 pounds annually.” Underand around the low tree layer, plant a shrub layer (such as currentsand berries). Next, surround these with herbs (primarily perennialherbs) and root vegetables, and complete the whole system witha ground cover, soil surface layer such as strawberries. You canalso build up in a vertical layer using grape vines or cucumbers.

Herb SpiralsHerb spirals are compact vertical gardens allowing forindividualized management of wind and water flow. Usea solid material, such as rocks or used bricks, to build thespiral frame. Ensure the center of the spiral is the highestpoint. Plant herbs that thrive in dryer soils and full sunat the top and use the various angles and heights to planwhere to plant herbs depending on their sun and waterdependence. The stone or brick walls provide heat retention,insulating the plant roots from cold snaps. Herb spiralscan also be built as swales that indent into the ground.Remember, in the northern hemisphere, water runs offin a clockwise direction, so be sure to build your spiral inthis same manner to work with the natural flow of water.Community Rebuilds also sources their straw bales (anagricultural co-product that was previously a bi-product)locally – within 100 miles. The organization also buildswith pine-bark beetle-killed wood sourced from within 100miles. Native plant species and rain gardens are the focusof landscapes surrounding Community Rebuilds’ houses.Lastly, the builds are completed by student interns, creatinga succession model of systems-thinking sustainable builders.SummaryPermaculture is more than food production – it is a design processthat can be applied to organizations, homes, and landscapes.This article aimed to highlight the theoretical and appliedelements of permaculture. Permaculture’s three ethics succinctlypresent the roots that hold together all that has been presented: Care for the earth Care for the people There are limits to growth (Holmgren, 2007)To care for the earth and people, and to recognize limits to growth,is to realize our need for regeneration. Regeneration of food andlandscapes, as opposed to degeneration, is a necessary standardfor environmental sustainability and applied permaculture.Glossary of TermsGarden Swale - Indented gardens that act as waterinfiltration basins.University of Massachussetts’ campus permaculture garden also featuresan herb spiral. This serves as a space organizer, visual attraction andwalkway for the campus garden - stacking functions!Permaculture in UtahA good example of permaculture concepts in action canbe seen with Community Rebuilds, a nonprofit buildingenergy-efficient straw bale housing for income-qualifyingfamilies in Moab, Utah. Community Rebuilds follows anenvironment-focused interactive housing design, takinginto account water systems (with a focus on rainwaterharvesting), sun cycles (building with passive solar), andmaterial sourcing. For material sourcing, CommunityRebuilds uses recycled products and agricultural co-productsin each build. They use earth removed for excavation ofthe home site when available by screening it and applying itback onto the walls as an ingredient in their earthen plasters.Herb Spiral - Herb spirals are compact vertical gardensallowing for individualized management of wind and waterflow.Permaculture - A design concept mimicking naturalecosystems.Plant Guild - Polyculture that blends several to many plantspecies working together.Regenerative Development - Designing humanenvironments that restore and regenerate as opposed todegenerating the surrounding environmentStraw Bale Construction - A method of building usingbales of straw as insulation. R-values (which gauge materialinsulating potential) typically range from 20-50.Systems Ecology - Systems ecology is an interdisciplinaryfield of ecology, taking a holistic approach to the study ofecological systems, especially ecosystems.5

SourcesBane, P. (2012). The permaculture handbook. BritishColumbia, Canada: New Society Publishers.Bell, G. (2004). The permaculture way: Practical steps tocreate a self-sustaining world. Hampshire, United Kingdom:Permanent Publications.Berry, W. (1981). Solving for pattern. In The gift of thegood land: Further essays cultural & agricultural, 134-149.Berkely, CA: North Point Press.Glanzberg, J. (2013, March). Permaculture and regenerativedesign. Presentation at Permaculture Interactive Series,Moab, UT.Hemenway, T. (2001). Gaia’s garden: A guide to home-scalepermaculture. White River Junction, Vermont: ChelseaGreen Publishing Company.Holmgren, D. (2003). Permaculture: Principles and pathwaysbeyond sustainability. Holmgren Design Services.Holmgren, D. (2007). Essence of permaculture. HolmgrenDesign Services.Lancaster, B. (2013). Rainwater harvesting for drylandsand beyond: Guiding principles to welcome rain into yourlife and landscape. Volume 1 2nd Edition. Tucson, AZ:Rainsource Press.Mang, P., & Reed, B. (2012). Designing from place: Aregenerative framework and methodology. Building Research& Information, 40(1), 23-38.McManus, B. (2010). An integral framework for permaculture.Journal of Sustainable Development, 3(3), 162-174.Mollison, B., & Holmgren, D. (1978). Permaculture one:A perennial agriculture for human settlements. TagariPublications.Nabhan, G. (2013). Growing food in a hotter, drier land:Lessons from desert farmers on adapting to climateuncertainty. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea GreenPublishing.Tainter, J. (2003). A framework for sustainability. WorldFutures, 59(3-4), 213-223.Holzer, S. (2004). Sepp holzer’s permaculture: A practicalguide to small-scale, integrative farming and gardening.White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green PublishingCompany.Utah State University is committed to providing an environment free from harassment and other forms of illegal discrimination based on race,color, religion, sex, national origin, age (40 and older), disability, and veteran’s status. USU’s policy also prohibits discrimination on the basis ofsexual orientation in employment and academic related practices and decisions. Utah State University employees and students cannot, because ofrace, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability, or veteran’s status, refuse to hire; discharge; promote; demote; terminate; discriminate incompensation; or discriminate regarding terms, privileges, or conditions of employment, against any person otherwise qualified. Employees andstudents also cannot discriminate in the classroom, residence halls, or in on/off campus, USU-sponsored events and activities. This publication isissued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture,Noelle E. Cockett, Vice President for Extension and Agriculture, Utah State University.6

Permaculture is a design concept for sustainable, food producing landscapes mimicking the diversity and resilience of natural ecosystems. Although concepts included in permaculture design have been in practice for millenia by various cultures worldwide, the term “permaculture” as it is