Transcription

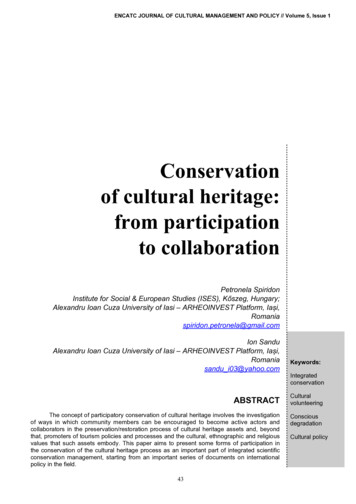

ENCATC Journal of Cultural Management and Policy // Volume 5, Issue 1Conservationof cultural heritage:from participationto collaborationPetronela SpiridonInstitute for Social & European Studies (ISES), Kőszeg, Hungary;Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi – ARHEOINVEST Platform, Iași,Romaniaspiridon.petronela@gmail.comPetronela Spiridon and Ion SanduAlexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi – ARHEOINVEST Platform, Iași,Romaniasandu CTCulturalvolunteeringThe concept of participatory conservation of cultural heritage involves the investigationof ways in which community members can be encouraged to become active actors andcollaborators in the preservation/restoration process of cultural heritage assets and, beyondthat, promoters of tourism policies and processes and the cultural, ethnographic and religiousvalues that such assets embody. This paper aims to present some forms of participation inthe conservation of the cultural heritage process as an important part of integrated scientificconservation management, starting from an important series of documents on internationalpolicy in the field.Consciousdegradation43Cultural policy

Petronela Spiridon and Ion Sandu // Volume 5, Issue 1Introductionof historical research (oriented to knowledge of theoriginal cultural context) (Spiridon et al, 2013).In general, the state of conservation of manyvery old cultural objects is impacted not just by theenvironment’s aggressiveness, but also by domesticand industrial activities and the levels of culturaland environmental education of the people. For thisreason the participatory approach investigates waysin which the community members from the regionswith tangible heritage value can be motivated toredefine their individual roles and responsibilitiesconsciously and voluntarily (Bass et al, 1995; Brown,1999; Sandu, 2013).In general, the conservation process aims tovalorise cultural and natural heritage assets and topreserve their historical messages (Sandu, 2004).In this regard a series of specific actions, measures,norms, principles, systems, techniques andintervention methods are undertaken and elaborated,infrastructures that are necessary, respectively, ininvestigation/research, preservation and restoration,direct or indirect, from the discovery/acquisition/transfer of the assets to their display/recovery/hoarding (E.C.C.O., 2008; Perusini, 2004).Conservation Science, as a new field, isinterdisciplinary, complex,global in character, bothInternationalscientific (theoretical) and“documents andtechnological (practical) andadopts the modern conceptevents in the fieldof integrated conservationThe new policies on the(Moldovan, 2010). Thisapproach to cultural heritageconcept aims to satisfy theconsider the safeguarding anddual purpose of preservinginclusion of cultural heritageand disseminating knowledgeassets within a global systemabout cultural heritage inof values, the developmentan integrated way, in closevenof cultural tourism as aconnection with socioif the conceptway of guaranteeing theeconomic and culturalright of access to culturedevelopment at micro andof integratedand the integration ofmacro level. Out of this grewconservation isactive participation of thethe concepts of collaborativepopulation in cultural heritageconservation and participatoryrelatively modern,conservation policy.conservation which focus onthe attempts toEven if the conceptstimulating all stakeholdersof integrated conservationinvolved in the processattract members ofis relatively modern, the(cultural, social, economic andthe public/communityattempts to attract membersenvironmental) and the activeto the activitiesof the public/communityinvolvement of the publicto the activities aimed atand community membersaimed at preservingpreserving cultural heritage(Spiridon, 2013). In this regard,cultural heritagehave a longer history. The rolerecently the importance hasof community in the culturalbeen highlighted of setting uphave a longerheritage conservation processa work team that, in additionhistory”.(preservation, restoration,to the conservator and therecovery and hoarding),renowned specialists in thewhich imply the concepts offield (curator, restorer, etc.),collaborative and participatoryshould include representativesconservation, started in 1964from the pure scienceswith the Venice Charter and continued over time(Geology and Mineralogy, Chemistry, Biology, Appliedthrough a series of international documents andScience, Environmental Science), from the fields ofevents, as we can see in table 1.technology and art history and even the membersThese documents and events describe, at(artists and local natives) of communities from regionsthe same time, the educational, interactive andwith tangible heritage value (Jo-Fan, 2012; Stoner,public-oriented role of the specialists operating in2005). This inter-multidisciplinary collaboration offersConservation Science which can be accomplishedsupport to the conservator in their work, not onlyby dissemination of information from historiographicalproviding support to investigate treatment options,research, technical-scientific and artistic investigation,find the materials and identify the techniques usedpreservation and restoration, by the design andby the artists, establish the date of manufacture anddevelopment of educational platforms in the fieldinvestigate the optimal materials (including from theand by providing advice and technical assistancecultural and ethnographic perspectives), but also toon cultural heritage (ICOMOS, 1990; Spiridon et al,provide contextualisation and justification of scientific2013).data through visual inspection and through the resultsE44

ENCATC Journal of Cultural Management and Policy // Volume 5, Issue 1YearDocument/eventPoint of interest1964The Venice CharterStates that the monumental works of the peoples are considered commonheritage and it is necessary to safeguard them for future generations in aresponsible way so as to hand them on in the richness of their authenticity(ICOMOS, 1964).1972The Heritage ConventionPromotes a general policy whereby cultural and natural heritage aims toperform an important function in community life.1990The Lausanne CharterEncourages local community involvement in cultural development (ICOMOS,1990).2002The Budapest DeclarationPuts more emphasis on the active involvement of local communities at alllevels in the conservation and management of World Heritage property(UNESCO, 2002).2003The Intangible Heritage ConventionRequests community participation in the process of conservation (UNESCO,2003).2003Code of Ethics, E.C.C.O.Mentions that the work of preservation/restoration is an activity of publicinterest and should be conducted in accordance with national andinternational law (E.C.C.O., 2003).2005The Faro ConventionRequests greater synergy between public heritage managementrepresentatives.2005European Cultural Heritage Forum The central point of discussion focusses on the active involvement ofinstitutions and individuals in the conservation of cultural heritage andorganised by Europa Nostra, ineven on the awareness of the personal benefits that may result from thiscollaboration with the Europeanattitude1.Economic and Social Committee(EESC), Brussels, 20052011The European Year of Volunteering2012La magna Charta del volontariato per Two documents developed by Cesvot – Centro Servizi Volontariato Toscana,i beni culturali (Velani & Rosati,Italia and Fondazione Promo P.A. which aim to create a framework2012)for recognition, scheduling and organisation of volunteering in culturalheritage.Guida all’uso del volontarioinformato2014Communication from the Commission “Cultural heritage is a shared resource, and a common good. ( ) Thesector offers important educational and volunteering opportunities for bothto the European Parliament, theyoung and older people and promotes dialogue between different culturesCouncil, the European Economicand generations. ( ) Therefore a more integrated approach to heritageand Social Committee and theconservation, promotion and valorisation is needed in order to take intoCommittee of the regions.account its manifold contribution to societal and economic objectives, asTowards an integrated approachwell as its impact on other public policies” (European Commission, 2014).to cultural heritage for Europe.A call to action for local administration representatives responsible for culturaland educational policies, trainers from public and private structures,associations and NGOs providing cultural services, and educationalprofessionals from cultural institutions, etc.Table 1. International Documents And EventsSource: Authors’ own elaboration.Some participatory conservationprinciplesfitting the new to the old, legibility of interventions andmonitoring the conservation status by making regularchecks (E.C.C.O., 2008; Worthing & Bond, 2008)were the main principles respected in the generalconservation process (preservation and restoration).Today the focus is on an integrated process ofscientific conservation (participatory conservation andstakeholder engagement). This approach is proposedby a series of documents and studies in the field, whichalso suggest a specific set of interdependent principlesThe fundamental principles that govern the rulesapplied in the cultural heritage conservation processare included in specialty literature and scientific practicebased on rules, orders, codes of ethics or conduct/laws, decrees, orders and decisions in the field. Untilvery recently, authenticity, importance of maintenance,minimum intervention, truth and honesty, reversibility,1For more information, see http://www.eesc.europa.eu/?i portal.en.press-releases.157045

Petronela Spiridon and Ion Sandu // Volume 5, Issue 1“The engagement of the community members in theparticipatory conservation process of cultural heritagerepresents an interdisciplinary and blended approach ofsocial science, art and scientific research which”.by differences in social, cultural and political contextsand because the level and form of participation by allactors can change over time (CDC/ATSDR, 1997;Brown, 1999; Waterton & Watson, 2011). At thesame time, the voluntary participation of communitymembers must be based on capacity to change,motivation to change and access to knowledge,with public information being a very importantelement in the integrated conservation process ofcultural heritage (Brown, 1999; ICOMOS, 1990).In our vision the main aspects of the participatoryconservation process could easily be represented asin figure 1, where we highlight the role of dialogueboth between the political, social, cultural andenvironmental representatives and those who belongto the scientific world (professionals, researchers,scientists, artists and even local traditionalistswith their techniques and methods) and betweenindividuals (members of public and community) andstakeholders.Participatory conservation includes a series ofactivities such as informing, listening, understanding,consulting, involving, collaborating and empoweringwhich help to: facilitate dialogue between all actors;mobilise and validate popular knowledge and skills;apply and adapt the science; and support communitiesand their institutions to manage and control resourceuse. As well as this it seeks to achieve sustainability,economic equity, social typology, justice and thepreservation of cultural integrity (CDC/ATSDR,1997; Bass et al, 1995; Brown, 1999; Negri, 2009).In this context the new participatory conservationapproaches act at three levels:to supplement it (The Improvement Service/ScottishCommunity Development Centre, 2011; Bass et al,1995; E.C.C.O., 2008; Laaksonen, 2010; Shah et al,2002; Waterton & Watson, 2011). These additionalprinciples must be brought to attention to co-ordinateand reconcile different and often conflicting interestsand to facilitate open debate in different contexts(social, cultural, economic, educational, environmental)based on values, knowledge, skills and the beliefs ofcommunity members while at the same time respectingEuropean and local rights (cultural, educationaland social) and promoting a model (“a culture”) ofcommunity involvement. In brief, having in mind thepassage from individual to structured engagement,these principles (essential to good practice andeffective participation) should be:———————Intrinsic motivation and voluntary participation;Extrinsic motivation (people need a reasonfor participation);Accessibility – equal rights and opportunitiesfor informed engagement (access andparticipation) in the cultural life of thecommunity;Mutual respect for history and culturaldiversity (between individuals and betweenprofessionals and community members);Flexibility – the community engagementsmust be adapted to the context;Transparent dialogue (suspend assumptions,listen and understand the expression of thecommunity’s traditions, etc.);Empower local people and communitymembers.—The forms of engagementThe engagement of the community members inthe participatory conservation process of culturalheritage represents an interdisciplinary and blendedapproach of social science, art and scientificresearch which contributes to respecting Europeancultural rights to access and participation in culturallife (Laaksonen, 2010). The challenge in thiscontext is to identify the form of participation bestsuited to a particular circumstance because theparticipatory process is dynamic, strongly influenced2—See n and prevention throughcommunication and information sessions,for example: interactive seminars andworkshops, interviews, phone-ins, emailnetworks and voluntary agreements;Investigation and research through inclusionof community members in interdisciplinaryscientific research teams and throughinnovative, integrative and participatorymethods for cultural and environmentaleducation, analysis and sharing like:Participatory Learning and Action, LivingLabs 2 and ICT platforms, e-learning

ENCATC Journal of Cultural Management and Policy // Volume 5, Issue 1Figure 1. Aspects of the participatory conservationprocessSource: Authors’ own elaboration.—finance the conservation work. Here we have asituation in which the public is involved in a passiveinteractive way in participatory conservation.technologies and online apps (for survey,analysis and monitoring);Storage and display: exhibitions usingtraditional and modern infographics,digital methods, augmented reality, projectmapping, etc.All of these aspects lead to a typology of participationforms which can be identified easily in the complexprocess of the integrated conservation of culturalheritage. As we can see in table 2, these formshighlight the passage from individual, involuntaryengagement to actions that are very well thoughtout by the functional groups lately integrated into theNGOs.Where cultural heritage assets are partof the everyday life of community members, theparticipation by them in the conservation processis practically involuntary by use. A very intuitiveexample in this sense may be found just byobserving the doorknob of the main entrance to theGyör Basilica in Hungary (see photo 1).Passing from involuntary participation topassive-interactive participation, a very goodexample is found in Karlskirche in Vienna, where,in 2004, a temporary internal lift was constructed inorder to restore the cupola (see photo 2). The liftascends 32 metres and the scaffolding continuesfor another 25. The amazing part of this is the factthat the restoration process was conducted withoutrestricting visitor access, and what is more, thevisitors were stimulated in this way to sustain andPHOTO 1. INVOLUNTARYPARTICIPATION “BY USE”:MAIN ENTRANCE OF THEGYÖR BASILICA, HUNGARY,1000-1009 (DETAIL)Source: Petronela Spiridon, 2014.47

Petronela Spiridon and Ion Sandu // Volume 5, Issue cipation“by use”This level is most often found in communities where the members only Living “history” in the“use” the heritage and they are just receivers of the general information presentregarding cultural heritage assets in an informal way and participation issimply a pretence (photo 1).2Passive andpassiveinteractiveparticipationThe community members are invited to participate by being told what hasbeen decided or has already happened or will happen.Information is made formally through local communications, media tools orby using project mapping and augmented reality and offers the opportunityto people themselves to ask and reflect about the history of buildings,sites and other cultural elements of the area in which they live. This isactually the beginning of the passage from local/regional/national historyto personal history through those cultural elements of the residential area.At this level we can also find community members involved in the process ofpreservation and restoration of the cultural heritage assets. Having accessto the assets creates the possibility that community members may financethe conservation work (photo 2).3InteractiveparticipationAt the next level of participation the community members are involved in Promotion of culturalprofessional teams’ work (finding materials and identifying the techniques rightsused by the artists, establishing the date of manufacture and investigatingthe optimal materials, identifying the role and significance of some culturalheritage assets in and for local community, etc.), in joint analysis and thedevelopment of action plans regarding the community heritage. At thislevel participation can be seen as a right.4Participationfor material ornon-materialincentivesAt this level the people accept involvement only if they receive some reward: Access to informatione.g. farmers may provide fields and labour and for them rewards such as and educationfood, cash or other material incentives are important.Young people can be stimulated by e-learning technologies and onlineapps to participate in integrated learning processes (using innovativemethodologies like Living Labs and ICT platforms). At this level, access toinformation and education become part of the right of access to culture.5Volunteer/spontaneousparticipationThe community members participate by taking initiatives spontaneous S e l f - m o b i l i s a t i o n ,or organised independently of external institutions in order to change self-determinationsystems and retain control over how resources are used. As groups take and associationcontrol of local decisions and determine how available resources areused, so they have a stake in maintaining structures or practices. Selfmobilisation and volunteering is in fact an active way to reflect differentapproaches and traditions based on free choice, desire and motivation. Atthis level the people do not request reward as they are conscious of theircontribution to the general interests of the community or society.6ProfessionalNGOparticipationNGOs are like an inventory of different kinds of participation. Among the Empowermentmore important NGOs in the field we may mention: IUCN, Europa Nostra,ICOMOS, ICOM, ENCATC, ECOVAST, IUCN (state level, national level).7FunctionalparticipationAt this level participatory conservation (public/community participation) C o n s u l t a t i o n a n dis seen as an intrinsic part of collaborative conservation (stakeholder negotiationengagement); community members participate by being consulted or byanswering questions. Practically they are involved in social and culturalenquiries and surveys, in working groups and meetings to discussproblems and policy regarding local heritage; at this level creativity, selfexpression, self-confidence, freedom of opinion and expression arepromoted.“Manipulation”TABLE 2. TYPOLOGY OF PARTICIPATION IN THE INTEGRATEDCONSERVATION PROCESSSource: Authors’ own elaboration.Of participants (public/community members)not contributing financially but asking for materialor non-material incentives we have the examples ofLiving Labs and ICT platforms. In general the livinglab methodology builds a cooperative table setupbetween public administrations, research, final users48

ENCATC Journal of Cultural Management and Policy // Volume 5, Issue 1PHOTO 2. PASSIVE-INTERACTIVE PARTICIPATION: KARLSKIRCHEIN VIENNA, AUSTRIA, 1716-1737 (INTERNAL TEMPORARY LIFTAND VISITORS’ PLATFORM).Source: refurbishment-project/karlskirche church vienna.cfmhave a stake in maintaining structures or practices.The case of Rosia Montana from Romania is a highlyinstructive example in this sense:and local businesses in which each actor is receivingand delivering immaterial and material resources3.Another category of participation based on selfmobilisation, self-determination and associationincludes members who only participate when the topicis of their special interest, when they have somethingspecific to contribute, or when they are involved in aproject related to the domain of the community. Asgroups take control over local/national decisions anddetermine how available resources are used they3[On the] 3rd of June 2014 the peasant’sstruggle, based in the village of RosiaMontana obtained a stunning victoryin the Romanian Parliament. This wasfinal rejection of a mining law proposal,initiated by the government, which wouldSee, for example, onte49

Petronela Spiridon and Ion Sandu // Volume 5, Issue 1PHOTO 3. VOLUNTEER/SPONTANEOUS PARTICIPATION –PUBLIC MOBILISATION IN THE CASE OF ROSIA MONTANA,ROMANIASource: ation/very good example of this kind of public participationis the case of the Kamehameha I monument inNorth Kohala, Hawai’i. The monument is a culturalhybrid in that it has deeply embedded features ofboth Hawaiian and Western cultures. Originally goldleafed and chemically painted, the monument wasrepainted and celebrated by its local communityeach year on Kamehameha Day. Public dialogueabout how to conserve the monument was used as avehicle for community engagement in critical thinkingabout representations of Hawai’i’s past. Opening theconservation process on conflicting interests in thecommunity required a reflexive approach in whichtraditional conservation analysis was only one ofmany ways by which to assess the significance ofthe monument (Wharton, 2003; Korza, 2002). Byanalysing this example in depth we can highlight thestakeholder engagement which refers to a frameworkof policies, principles and techniques which ensurethat citizens and communities, individuals, groups andorganisations have the opportunity to be engaged ina meaningful way in the process of decision-makinghave given permit to the largest goldmining operation in Europe. The rejectionhas come as a result of tremendouspublic mobilization [photo 3], in supportof peasant rights who fight to protect theirland in Romania (Szocs, 2014).A participatory model based on public accessto cultural heritage assets explores ways to designparticipatory platforms so that the local traditions,historical and cultural values regarding heritageassets, and even the content that amateurs createand share is communicated, displayed and valorisedattractively (Bass et al, 1995; Simon, 2010).Finally, functional participation is that inwhich the community members participate by beingconsulted or by answering questions. Practicallythey are involved in social and cultural enquiries andsurveys, in working groups and meetings to discussproblems and policy regarding local heritage. At thislevel, creativity, self-expression, self-confidence,freedom of opinion and expression are promoted. A50

ENCATC Journal of Cultural Management and Policy // Volume 5, Issue 1that will affect them, or in which they have an interest.Thus, public participation can be recognised as apractice of stakeholder engagement. In this way thestakeholder engagement (collaborative conservation)and public participation (participatory conservation)are a means of achieving (Yee, 2010):————an inland student and researcher personal supportsystem convergence programme” key project, whichis subsidised by the European Union and Hungaryand co-financed by the European Social Fund.Participatory democracy (communityempowerment and providing the opportunityto develop knowledge for making informedchoices);Transparency in decision-making process;Community empowerment and support;Reduced conflict over decisions betweendecision-makers and public groups, andbetween the groups.ReferencesBASS, S.; DALAL-CLAYTON, B.; PRETTY, J. (1995)Participation in strategies for sustainabledevelopment. Environmental Planning Issues, 7 (May1995). International Institute for Environment andDevelopment. London, United Kingdom, 118 pp.BROWN, N.A. (coord.). (1999) A Guide to TeachingParticipatory and Collaborative Approaches toNatural Resource Management. St. Lucia, USA:Caribbean Natural Resources Institute (CANARI).Available at: http://www.canari.org/267guide.pdfConclusionThe concepts of community engagement andparticipatory involvement are not new, though,generally, they have been used more in the socialfields of healthcare and services than in culturalheritage conservation science. But participatoryconservation is more than a concept, in fact it givesus a powerful means to respect the cultural rightsto access and participate in cultural life blendedwith other individual rights such as access toinformation and education, freedom of opinionand expression, self-mobilisation and association.Respecting and applying these rights determines theaccountability of community members and causesincreasing involvement of the community in heritageconservation. The involvement in integrated platformsfor cultural and environmental education andinformation, inclusion in professional teams’ work, injoint analysis, development of action and promotionplans, make community heritage accessible toeveryone.In this context, we consider that future studiesregarding the active involvement/participatoryengagement of the community members in thebroader process of conservation of cultural heritageassets must involve studies of the incidence ofconscious deterioration/degradation of the culturalheritage assets (causes of vandalism, ignorance,negligence, carelessness or inattention) reportedin the current integrated platforms for cultural andenvironmental education and information. At the sametime, an analysis of the relationship between the levelof education and enculturation of the communitymembers and the level of the voluntary and activeinvolvement in conservation and promotion ofcommunity heritage could be relevant.CDC/ATSDR (1997) Principles of Community Engagement.Atlanta, GA: Committee on Community Engagement.Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/phppo/pce/E.C.C.O. (2003) Professional Guidelines (II): Code ofEthics.E.C.C.O. (2008) Draft of European Recommendation for theConservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage.Bruxelles.EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from theCommission to the European Parliament, theCouncil, the European Economic and SocialCommittee and the Committee of the Regions.Towards an integrated approach to cultural heritagefor Europe. Brussels, 2014. Available at: 014heritage-communication en.pdfICOMOS (1964) Venice Charter. Venice.ICOMOS (1990) Charter for the protection and managementof the archaeological heritage. Lausanne.ICOMOS (1999) Burra Charter – The Australia ICOMOSCharter for Places of Cultural Significance. Availableat: -Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdfJO-FAN, H. (2012) Data and interpretation: enhancingconservation of art and cultural heritage throughcollaboration between scientist, conservator, and arthistorian. IOPscience, IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci.Eng. 37 012003, 1-6. Available at: ZA, P. (2002) The Kamehameha I Statue ConservationProject. Case Study: Hawai’i Alliance for ArtsEducation. Available at: documents/labs/hawaii casestudy.pdfLAAKSONEN, A. (2010) Making culture accessible –Access, participation and cultural provision in thecontext of cultural rights in Europe. Barcelona:Council of Europe Publishing.AcknowledgementsThis research was realised in the framework ofthe TÁMOP 4.2.4.A/2-11-1-2012-0001 “NationalExcellence Programme – Elaborating and operatingMOLDOVAN, A. (2010) Conservarea preventivă a bunurilorculturale. IVth edition, Cetatea de Scaun, Târgoviște.51

Petronela Spiridon and Ion Sandu // Volume 5, Issue 1NEGRI, M. VoCH-Volunteers for Cultural Heritage:il progetto nel contesto europeo. In: Da Milano,C.; GIBBS, K.; SANI, M. (2009) Il volontariato neimusei e nel settore culturale in Europa. Ljubljana:Associazione Slovena Musei.Modern Techniques in Conservation andAnalysis Proceedings of the National Academy ofSciences”, 40-57. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11413.htmlSZOCS, A. (2014) Victory for Romanian peasants overgold mining corporation. Agricultural and RuralConvention, 18 June 2014. Available at: rporation/#.U6MWmsJLeIY.facebookPERUSINI, G. (2004) Il restauro dei dipinti e delle sculturelignee. Storia, teorie e tecniche. Udine: Del BiancoEditore.SANDU, I. (2004) Nomenclatura patrimoniului cultural. Iași:Ed. Performantica.THE IMPROVEMENT SERVICE/ SCOTTISH COMMUNITYDEVELOPMENT CENTRE. (2011) CommunityEngagement Elected member briefing note,7. Available at: SANDU, I. (2013) Aspecte interdisciplinare ale științeiconservării patrimoniului cultural, InternationalWorkshop Scientific, tech

data through visual inspection and through the results of historical research (oriented to knowledge of the original cultural context) (Spiridon et al, 2013). In general, the state of conservation of many very old cultural objects is impacted not just by the environment's aggressiveness, but also by domestic