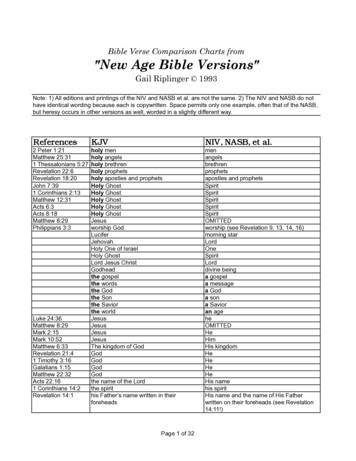

Transcription

On the Holy Spirit(Pneumatologia)byJohn Owen(1616-1683)A DISCOURSE CONCERNING THE HOLY SPIRITIN WHICHAN ACCOUNT IS GIVEN OF HIS NAME, NATURE, PERSONALITY, OPERATIONS, AND EFFECTS;HIS WHOLE WORK IN THE OLD AND NEW CREATION IS EXPLAINED; THE DOCTRINECONCERNING IT IS VINDICATED FROM OPPOSITION AND REPROACH.THE NATURE AND NECESSITY OF GOSPEL HOLINESS; THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN GRACEAND MORALITY — OR A SPIRITUAL LIFE LIVED TO GOD IN EVANGELICAL OBEDIENCE,AND A COURSE OF MORAL VIRTUES — ARE STATED AND DECLARED.PART IBOOKS I THROUGH V"Search the Scriptures " — John 5.39Ἐκ τῶν θείων γραφᾶν θεολογοῦμεν, καὶ θέλωσιν οἱ ἐχθροὶ, καὶ μή.Out of the written word of God come Divine teachings, though His enemies may not wish it.— CHRYSOSTOMLondon:1674.

fromTHE WORKS OF JOHN OWENEDITED BYWILLIAM H. GOOLDVOLUME 3This Edition ofTHE WORKS OF JOHN OWENfirst published by Johnstone & Hunter, 1850-53Books I through Vwere published in 1674.Books VI through IXwere published in 1677In this edition, book VI began again at page 1.Modernized, formatted, corrected, and annotated (in blue) by William H. Gross www.onthewing.org Mar 2011Except where indicated,Scripture in the footnotes is taken from the New King James version,Thomas Nelson, Publishers, 1982.Last updated 11/10/2015

CONTENTSEditor's NotePrefatory note.Analysis.To the Readers.Book I.Chapter I. General principles concerning the Holy Spirit and his work.Chapter II. The name and titles of the Holy Spirit.Chapter III. Divine nature and personality of the Holy Spirit proved andvindicated.Chapter IV. Particular works of the Holy Spirit in the first or old creation.Chapter V. Way and manner of the divine dispensation of the Holy Spirit.Book II.Chapter I. Particular operations of the Holy Spirit under the Old Testamentpreparatory for the New.I. Extraordinary Works of the Spirit.1. Prophecy2. The Writing of Scripture3. MiraclesII. Ordinary Works of the Spirit.1. In respect to political things.2. In respect to moral virtues.3. In respect to natural abilities.4. In respect to the intellect.Chapter II. General dispensation of the Holy Spirit with respect to the newcreation.Chapter III. Work of the Holy Spirit with respect to the head of the newcreation - the human nature of Christ.Christ as Head of the ChurchI. Respecting the Person of Jesus ChristChapter IV. Work of the Holy Spirit in and on the human nature of Christ.II. Respecting Others on behalf of ChristChapter V. The general work of the Holy Spirit in the new creation withrespect to the members of that body of which Christ is the head.Book III.Chapter I. Work of the Holy Spirit in the new creation by regeneration.Chapter II. Works of the Holy Spirit preparatory to regeneration.Chapter III. Corruption or depravation of the mind by sin.Chapter IV. Life and death, natural and spiritual, compared.

Chapter V. The nature, causes, and means of regeneration.Chapter VI. The manner of conversion explained in the instance of Augustine.Book IV.Chapter I. The nature of sanctification and gospel holiness explained.Chapter II. Sanctification is a progressive work.Chapter III. Believers are the only object of sanctification, and subject ofgospel holiness.Chapter IV. The defilement of sin, what it consists in, with its purification.Chapter V. The filth of sin is purged by the Spirit, and the blood of Christ.Chapter VI. The positive work of the Spirit in the sanctification of believers.Chapter VII. Of the acts and duties of holiness.Chapter VIII. Mortification of sin, the nature and causes of it.Book V.Chapter I. Necessity of holiness from the consideration of the nature of God.Chapter II. Eternal election is a cause of and motive for holiness.Chapter III. Holiness is necessary from the commands of God.Chapter IV. Necessity of holiness from God's sending Jesus Christ.Chapter V. Necessity of holiness from our condition in this world.

Editor's NoteThis is a restatement and simplification of John Owen's original work, but not aparaphrase. Its purpose is to make it more accessible to a modern audience ofbelievers, not just theologians. You may reproduce the text so long as you do notchange it or sell it to anyone. This restriction is placed on it so that thepropagation of any errors in the modernized language is limited. If someonerephrases my rephrasing, the treatise will quickly degenerate into a misstatementrather than a restatement of Owen's work.What changes have been made?The old English wording has been modernized, so that "thee" and "thou" arenow "you" and "yours." American spelling has been largely employed (laborinstead of labour). Inline scripture references may be superscripted to aidreadability. Additional references are superscripted in blue. Roman numerals werechanged to Arabic and corrected as needed. The difficult structure and syntaxwere simplified. Sentences in many cases were split into several sentences forease of reading. Parallelism has been employed to maintain rhythm and clarity.The word "peculiar" is variously rendered "particular", "unique", "special," or"specific," depending on the context. Unreferenced pronouns and "understood"words have been made explicit. Now, Owen may have left personal pronounsambiguous to reflect the mystery of the Godhead; but it was more obscure thanmysterious. The passive voice is often changed to active. Duplicated texts,digressions not affecting the content, and alternate phrasings within the samesentence, have been removed for easier comprehension. Little-used words haveeither been annotated or replaced with simpler ones. Owen's wordiness has beenreduced where possible. Formatting has also been revised (paragraph and pagebreaks, bullet points, etc.).There are two unusual uses of language that have been retained in the text. Thefirst is Owen's repeated use of "afterward" — "it will be fully explainedafterward." He doesn't mean at some unspecified time later in the book. Hemeans it in a sequential and orderly sense. He will first handle the topic at hand,and then get to the other aspect immediately "afterward."The second unusual use of language involves the words "act, actings, actual, andactually." He uses the transitive form; we tend to use the intransitiveprepositional form. We say that we "act in faith," or we "act under grace," andthe Spirit imparts the grace that we act under. But Owen says that the Holy Spirit"acts grace" in us, and we "act faith" (rather than "act out our faith"). Actings are

repeated acts of this kind; actual and actually are the proper adjectival andadverb forms of "act" (whereas today we use those forms to mean real andreally). Owen describes a God-given "principle" – not a value, but an ability or acompelling power in us — that we act, or actuate, according to its purposes. Weact the graces that He communicates to us by this principle. So, the Spiritimparts this principle to us, employing it to effect its purposes, using its realpower in and through us, to produce its intended effects. And we freelyparticipate by acting it — i.e., by putting that principle into gracious and holyaction using our regenerated faculties. But in some instances, "acted" waschanged to "moved," to be less distracting.Language today continues to deteriorate as visual and auditory media replacewritten media. So Goold's mid-19th century prefatory and analytical notes, havealso been modernized a bit to ensure they are more readily understood. ORIGINALNOTES are in black, some ending with "— Ed." My notes are in blue, someending with "— WHG." All page number references are the original pagenumbers of the 1850-53 edition, which are displayed intra-text.Latin, Greek, and Hebrew phrases have either been removed from the body ofthe text (where they were more of a distraction than a help), or Anglicized withthe Strong's number (NT:xxxx or OT:xxxxx). Some required clarifying text tomake the point explicit. But Owen's full argument, supporting text, and styleremain, as do William Goold's footnotes in their original languages. If youwould like the digitized 1853 edition, with appendices cross-referencing both theScriptures and original language used in the text, please consult CCEL's ml.My aim is not to preserve Owen's text, but his teaching. It would be a shame if amodern audience didn't benefit from his labors because his language was toocomplex, archaic, or arcane to grasp. As with each of these restatements, I hopethis one makes it more accessible to you, bringing home the wonder andimportance of the doctrines of the Holy Spirit that Dr. Owen drew fromScripture, and vividly explains here.There are few works on the Holy Spirit that have not been influenced by theHoliness movement of the 1800s, or the Charismatic movement of the 1920s.And there are few if any scholarly works outside those movements, that haven'tdrawn on this particular work of Dr. Owen to bring balance back to our view ofthe person and work of the Holy Spirit. Please read William Goold's PrefatoryNote to understand where this treatise fits with regard to Quakers and Quietism,

which was just then arising. See also the note on p. 527, and Owen's causticdescription on p. 556.In Owen's introduction, "To the Readers," you'll see the same objections to dryrationalism that Jonathan Edwards later expressed in his treatise on ReligiousAffections (1746). Yet both men objected as well to the unfounded emotionalismthat was rampant in their day — the term used then was "enthusiastic" or"enthusiasm." They weren't decrying passionate belief. Rather, they insisted thatour passion must be born, provoked, and enlarged only by God's truth. Bothextremes, cold intellectualism and wild enthusiasm, remain evident in our ownday; and so the balance that Owen provides here is still greatly needed, and itwill be useful to every believer.Over the past 350 years, scholars have improved little upon Dr. Owen's labors.He gave glory to God by relying solely on the authority of Scripture for thethings which he taught, as the contents of this treatise will amply demonstrate. Itis a profound and wonderful work: I pray that you may enjoy and be edified byit. It has such a repetition and rhythm to it — of the doctrines, principles, andtext of Scripture concerning God's Spirit — that you needn't worry if you don'tget it all at the first reading of a portion. He will so drive it, drive it, drive itthroughout, that it becomes fixed in your heart and soul — at least, it has mine.William H. Grosswww.onthewing.org Mar 2011

Prefatory note.The year 1674 saw, issuing from the press, some of the most elaborateproductions of our author. Besides his own share in the Communion controversy,he published in the course of that year the second volume of his "Exposition ofthe Epistle to the Hebrews," and another folio of equal extent and importance:the first part of his work on the Holy Spirit. For what is generally known underthe title of "Owen on the Holy Spirit," is but the first half of a treatise on thatsubject. The treatise was completed in successive publications: "The Reason ofFaith," in 1677; "The Causes, Ways, and Means of Understanding the Mind ofGod," etc., in 1678; "The Work of the Holy Spirit in Prayer," in 1682; and in1693 two posthumous discourses appeared, "On the Work of the Spirit as aComforter, and as the Author of Spiritual Gifts." From the statements of Owenhimself in various parts of these works, as well as on the authority of NathanielMather, who wrote the preface to the last of them, we learn that they were allincluded in one design, and must be regarded as one entire and uniform work.In Owen's preface to the "Reason of Faith," he expressly states,About three years ago I published a book about the dispensation and operations of the Spirit of God.That book was only one part of what I designed on that subject. The consideration of the work of theHoly Spirit as the Spirit of illumination, of supplication, of consolation, and as the immediate author ofall spiritual offices and gifts, extraordinary and ordinary, is designed for the second part of it.Uncertain, as he advanced in years, whether he would be spared to finish it,Owen was induced to separately issue the treatises belonging to the second part,according to his ability under the pressure of other duties, to overtake thepreparation and completion of them. They are now collected for the first time,and arranged into the order which, it is believed, the author would have had themif he lived to publish an edition comprehending all his treatises on the HolySpirit in the form and under the title of one work. No other liberty, however, hasbeen taken with these treatises than simply to number the four of them whichwere published separately, and to include the contents of the next volume as somany additional books; thus it continues and completes the discussion of thesubject which had begun and was prosecuted in the five previous books that areembraced in this volume. To all of them, the general designation pneumatologiais equally applicable. Thus arranged and seen in its full proportions, the workamply vindicates the commendation bestowed on it, as the most completeexhibition of the doctrine of Scripture on the person and agency of the Spirit "tobe found in any language." No author had previously attempted to address "the1whole economy of the Holy Spirit, with all his adjuncts, operations, and

effects," Owen pleads extenuating circumstances for any lack of system andlucid order in his work. If such an attempt had never previously been made, it isequally true that no successor has been found in this walk of theology who hasventured to compete with Owen in the laying down and systematic discussion ofthis great theme. Treatises of eminent ability and value have appeared onseparate departments of it. But in the wide range embraced in this work ofOwen, as well as in the power, depth, and resources conspicuous in everychapter, it is not merely first, but single and alone in all our religious literature.The work, as we may gather from various allusions in it, was written in2opposition to the rationalism of the early Socinians, especially as represented by3Crellius; to the mysticism of the Quakers, a sect which had grown into notorietywithin thirty years before the publication of this work; and to the irreligion of atime when the derision of all true piety was the passport to royal favor. Thatfanaticism of various kinds should appear during the religious fervors of thecommonwealth, is no more strange than, when genuine coin is in circulation,attempts are made to replace it with what is counterfeit and base. Against suchfanaticism it was natural that a reaction would ensue. Certain divines panderedto the blind prejudice of the times succeeding the Restoration, by sarcasticinvective against all that was evangelical in the creed of the Puritans and vital in4personal godliness. Samuel Parker was infamous in his subservience to themalice of the Court against dissent, and even against the common interests ofProtestantism. He distinguished himself in his assault upon the doctrines of graceand the distinctive principles of the Christian faith. Owen accordinglyadministers a rebuke to him in terms as severe as the calm dignity of his temperever allowed him to employ in controversy. But the prominent aim in his wholework is to distinguish the gracious operations of the Spirit in the hearts ofbelievers, from the excesses of fanaticism. On the one hand, whether as itappeared in the ruder sects of the age or in the more genial mysticism of theQuaker, Owen elevated his subjective experience of a spiritual light to coordinate authority with the objective revelation of God in the word. On the otherhand, he distinguished it from the morality which, having no gracious principleto guide it, scarcely tolerated an appeal to the only divine code there is for theregulation of human conduct.This comprehensive treatise abounds in more than Owen's usual wordiness. Thatfeature of the work may, perhaps, be explained by the consciousness underwhich the author always seems to labor when he is prosecuting an argument withopponents, rather than dealing with the conscience in a treatise on practical

religion. He moves heavily, as if he were armored for conflict rather than girdedfor useful work. As he proceeds, however, the interest deepens; weightyquestions receive clear elucidation; practical difficulties are judiciously resolved;and momentous distinctions, such as those between gospel holiness and commonmorality, and between natural and moral inability, are skillfully given. Indeed,many points which he brings out with sufficient precision, when stripped of thewordiness which encumbers them, are found to be identical with certain modesin the presentation of divine truth which have been deemed the discoveries andimprovements of a later theology. No work of the author supplies better evidenceof his pre-eminent skill in what may be termed spiritual ethics. He traces theeffect of religious truth on the conscience, and the varied phases of humanfeeling as modified by divine grace and tested by the divine word. Hisreasonings would have been reputed highly philosophical if they had not been sovery scriptural.It is in reference to the following work that Cecil, an acute and rather severejudge of books and authors, has observed, "Owen stands at the head of his classof divines. His scholars will be more profound and enlarged, and betterfurnished, than those of most other writers. His work on the Spirit has been mytreasure-house, and one of my very first-rate books." A good abridgment of it bythe Rev G. Burder has appeared in more than one edition.In 1678, Dr. Clagett, preacher to the Honorable Society of Gray's Inn, and one ofhis Majesty's chaplains in ordinary, in "A Discourse concerning the Operation ofthe Holy Spirit," etc., attempted "a confutation of some part of Dr. Owen's workon that subject." Mr. John Humfrey, in his "Peaceable Disquisitions," criticizedthe spirit in which Clagett had dealt with Owen. Clagett published anothervolume, and promised a third on the opinions of the Fathers respecting the pointsat issue. The manuscript of this last volume was lost in a fire which consumedthe house of a friend with whom it had been lodged. Henry Stebbing publishedin 1719 an abridgment of the first two volumes. The principles of the work arenot evangelical; a tone of cold pedantry pervades it; and the author seems asmuch influenced by a desire to differ from Owen as to discover the truth inregard to the points on which they differed.Analysis.The FIRST BOOK of the treatise is devoted to considerations of a general andpreliminary nature. The promise of spiritual gifts contained in Scripture isexamined; and from this occasion is taken to illustrate in chapter 1 the

importance of sound views on the doctrine of the Spirit,from the place it holds in Scripture;from the abuses practiced under His name;from certain pretenses that were urged toward an inward light, thatwere inconsistent with the claims of the Spirit of God;from many dangerous opinions which had become prevalent respectingHis work and influence; andfrom the opposition directly offered to the Spirit and His work in theworld.In chapter 2 the name and titles of the Holy Spirit are considered. The evidenceof his divine nature and personality follows,from the formula of our initiation into the covenant; Mat 28.19from the visible sign of His personal existence; Mat 3.16from the personal properties ascribed to Him;from the personal acts He performs; andfrom those acts towards Him on the part of men which imply hispersonality.In chapter 3, we have a short proof of his Godhead, from the divine names hereceives, and the divine properties ascribed to him; it is appended to theargument in illustration of his personality. In chapter 4, the work of the Spirit inthe old creation in reference to the heavens, to the earth, to man, and to thecontinued sustentation of the universe, is fully explained. In chapter 5, thedispensation of the Spirit is illustrated in reference to the Father as giving,sending him, etc., and in reference to His own voluntary and personal agency asproceeding, coming, etc.4In the SECOND BOOK, the particular operations of the Holy Spirit under the OldTestament, and in preparation for the new, are considered, such as prophecy,inspiration, miracles, and other gifts (ch. 1); the importance of the Holy Spirit inthe new creation is proved by the fact that he is the subject of the great promisein sacred Scripture respecting new testament times (ch. 2). His work in referenceto Christ is unfolded under a twofold aspect —1. As it bore on Himself, in framing Christ's human nature; sanctifying it in the5instant of conception, filling it with the needful grace, anointing it withextraordinary gifts, conveying to it miraculous powers, guiding, comforting,and supporting Christ, enabling him to offer himself without spot to God,

preserving his human nature in the state of the dead, raising it from the grave,and finally glorifying it (ch. 3); and,2. As He secures, throughout successive ages, a sound and explicit testimony tothe person and work of Christ (ch. 4). General considerations are urgedregarding the work of the Spirit in the new creation, as it relates to the mysticalbody of Christ — to all believers (ch. 5).The THIRD BOOK is occupied with the subject of regeneration as the special workof the Spirit. It is shown not to consist in baptism merely, or externalreformation, or enthusiastic raptures (ch. 1). The operations of the Spiritpreparatory to regeneration are exhibited, such as illumination, conviction, etc.(ch. 2). Two important chapters of a digressive character follow, in which thecondition of man by nature is stated, as spiritually blind and impotent (ch. 3),and as spiritually dead (ch. 4). The true nature of regeneration is next illustrated— first negatively, in which it is proved not to consist in any result of moralpersuasion (moral persuasion being defined and the extent of its efficacy beingfixed). No change which it can effect can be viewed as tantamount toregeneration, because,1. It leaves the will undetermined;2. It imparts no supernatural strength;3. It is not all we pray for when we pray for efficient grace (ch. 4); and4. It does not actually produce regeneration or conversion.Regeneration is then considered positively, as implying all the moral operationwhich means can effect; and not only a moral but a physical and immediateoperation of the Spirit; and the irresistibility of this internal efficiency on theminds of men. Explanations are given as to the effect that, in regeneration, theHoly Ghost acts according to our mental nature; He does not act upon us by aninfluence such as inspiration; and He offers no violence to the will. Then threearguments are given in support of this view of regeneration — from theconferring of faith by the power of God, from the victorious efficacy of internalgrace as attested by Scripture, and from the nature of the work itself as describedin various terms of Scripture, "quickening," "regeneration," etc.; and also fromthe terms in which the effect of grace on the different faculties of the soul isrepresented (ch. 5). The manner of conversion is then explained in the instanceof Augustine, the account by that eminent father of his own conversion beingselected to illustrate both the outward means of conversion, and the variousdegrees and effects of spiritual influence on the human mind (ch. 6).

The FOURTH BOOK discusses the doctrine of sanctification, which is presented asthe process completing what the act of regeneration has begun. A general view isthen given of the nature of sanctification, as consisting in 1. external dedication;and 2. internal purification (ch. 1). Its progressive character is unfolded (ch. 2);and it is proved that it is a gracious process, extending to believers only (ch. 3).Sanctification is illustrated as it relates to the removal of spiritual defilement;and it is proved that man cannot purge himself from his natural depravity (ch. 4).It is shown how the Spirit and blood of Christ are effectual to purge the heart andconscience — the Spirit efficaciously, the blood of Christ meritoriously, faith asthe instrumental cause, and afflictions as a subordinate instrumentality (ch. 5).The positive work of sanctification follows, embracing evidence of twopropositions:1. That the Spirit implants a supernatural habit and principle enabling believersto obey the divine will, and differing from all natural habits, bothintellectual or moral; and,2. That grace is requisite for every act of acceptable obedience.Under the first proposition, four things are considered — 1) the reality of theprinciple asserted; 2) its nature in inclining the will; 3) the power as well as theinclination that it imparts; and lastly, 4) its specific difference from all otherhabits (ch. 6). Under the second proposition the acts and duties of holiness arereviewed, and proof is supplied of the necessity of grace for them (ch. 7). Thenature of the mortification of sin, as a special part of sanctification, isconsidered; directions for this spiritual exercise are given; particular means forthe mortification of sin are specified; and certain errors respecting this duty arecorrected (ch. 8).The FIFTH BOOK simply contains arguments for the necessity of holiness — fromthe nature of God (ch. 1); from eternal election (ch. 2); from the divinecommands (ch. 3); from the mission of Christ (ch. 4); and from our condition inthis world (ch. 5). — Ed.

5To the Readers.An account in general of the nature and design of the ensuing discourse, with thereasons why it is made public at this time, is given in the first chapter of thetreatise itself. Therefore I will not detain the readers long at its introduction. Buta few things are necessary to acquaint them with, both as to the matter containedin it and as to the manner of its handling. The subject-matter of the whole, as thetitle and almost every page of the book declares, is the Holy Spirit of God andhis operations. There are two things to be addressed, either of which aresufficient to render any subject either difficult on the one hand, or unpleasant onthe other. We have both to conflict with in this treatise: for where the matteritself is abstruse and mysterious, it cannot be handled without its difficulties; andwhere it has fallen under public contempt and scorn by any means whatever,there is an abatement of satisfaction in its consideration and defense. Now, allthe concerns of the Holy Spirit are an eminent part of the "mystery" or "deepthings of God;" for just as the knowledge of them wholly depends on and isregulated by divine revelation, so they are divine and heavenly in their ownnature. They are distant and remote from all things that the heart of man can riseup to in the mere exercise of its own reason or understanding. Yet, on the otherhand, there is nothing in the world that is more generally despised as foolish andcontemptible than the things that are spoken of and ascribed to the Spirit of God.If a fanatic dares to avow an interest in the work of the Spirit, or if he takes uponhimself its defense, he needs no help to forfeit his reputation with many, as beingestranged from the conduct of reason and all generous principles ofconversation. Therefore these things must be spoken of a little, if only tomanifest where relief may be had against the discouragements which attendthem.For the first thing proposed, it must be granted that the things addressed here arein themselves mysterious and abstruse. Yet the way by which we may endeavorto acquaint ourselves with them, "according to the measure of the gift of Christto every one," Eph 4.7 is made plain in the Scriptures of truth. If this way isneglected or despised, then all other ways of attempting the same end, howevervigorous or promising they may be, will prove ineffectual. It is not my presentwork to declare or be diverted by what belongs to the inward frame anddisposition of mind in those who search to understand these things, or whatbelongs to the outward use of means, or to the performance of spiritual duties,and the conformity of the soul to each discovery of truth that is attained. If God

gives an opportunity to address the work of the Holy Spirit in enabling us tounderstand the Scriptures, or to understand the mind of God in them, then thewhole of this will be declared at large.At present, it may suffice to observe that God, who in himself is the eternaloriginal spring and fountain of all truth, is also the only sovereign cause andauthor of its revelation to us. The truth, which originally is one in God, is ofvarious sorts and kinds according to the variety of things respectivelycommunicated to us.6The ways and means of that communication are suited to the distinct nature ofeach truth in particular. So the truth of natural things is made known from Godby the exercise of reason or the due application of the understanding that is inman for their investigation; for "the spirit of the man knows the things of a man."1Cor 2.11 Ordinarily there is nothing more required for that degree of certainty ofknowledge in things of that nature of which our minds are capable, than thediligent application of the faculties of our souls; the due use of proper means willattain this. Yet there is a secret work of the Spirit of God in this, even in thecommunication of skill and ability in natural things, in civil things, in moral,political, and artificial things, as fully manifested in our ensuing discourse. Butbecause these things belong to the work of the old creation and its preservation,or to the rule and government of mankind in this world as rational creatures, nouse of means, and no communication of aids, whether spiritual or supernatural,is absolutely necessary to be exercised or granted about them. Therefor

Chapter III. Divine nature and personality of the Holy Spirit proved and vindicated. Chapter IV. Particular works of the Holy Spirit in the first or old creation. Chapter V. Way and manner of the divine dispensation of the Holy Spirit. Book II. Chapter I. Particular operations of the Holy Spirit