Transcription

Un-Settling Middle Eastern RefugeesThis open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

FORCED MIGRATIONGeneral Editors: Tom Scott-Smith and Kirsten McConnachieThis series, published in association with the Refugees Studies Centre,University of Oxford, reflects the multidisciplinary nature of thefield and includes within its scope international law, anthropology,sociology, politics, international relations, geopolitics, socialpsychology and economics.Recent volumes:Volume 40Un-Settling Middle Eastern Refugees: Regimesof Exclusion and Inclusion in the Middle East,Europe, and North AmericaEdited by Marcia C. Inhorn and Lucia VolkVolume 39Structures of Protection? Rethinking RefugeeShelterEdited by Tom Scott-Smith and Mark E.BreezeVolume 38Refugee Resettlement: Power, Politics, andHumanitarian GovernanceEdited by Adèle Garnier, Liliana Lyra Jubilut,and Kristin Bergtora SandvikVolume 37Gender, Violence, RefugeesEdited by Susanne Buckley-Zistel andUlrike KrauseVolume 36The Myth of Self-Reliance: Economic LivesInside a Liberian Refugee CampNaohiko OmataVolume 35Migration by Boat: Discourses of Trauma,Exclusion and SurvivalLynda MannikVolume 34Making Ubumwe: Power, State and Camps inRwanda’s Unity-Building ProjectAndrea PurdekováVolume 33The Agendas of Tibetan Refugees: SurvivalStrategies of a Government-in-Exile in a Worldof Transnational OrganizationsThomas KauffmannVolume 32The Migration-Displacement Nexus: Patterns,Processes, and PoliciesEdited by Khalid Koser and Susan MartinVolume 31Zimbabwe’s New Diaspora: Displacement andthe Cultural Politics of SurvivalEdited by JoAnn McGregor and RankaPrimoracFor a full volume listing, please see the series page on our d-migrationThis open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

Un-Settling Middle EasternRefugeesREGIMES OF EXCLUSION AND INCLUSION INTHE MIDDLE EAST, EUROPE, AND NORTH AMERICAEdited byMarcia C. Inhorn and Lucia VolkberghahnNEW YORK OXFORDwww.berghahnbooks.comThis open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

First published in 2021 byBerghahn Bookswww.berghahnbooks.com 2021 Marcia C. Inhorn and Lucia VolkAll rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passagesfor the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this bookmay be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic ormechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any informationstorage and retrieval system now known or to be invented,without written permission of the publisher.Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataNames: Inhorn, Marcia C. Volk, Lucia, editor.Title: Un-Settling Middle Eastern Refugees: Regimes of Exclusion and Inclusion in theMiddle East, Europe, and North America / edited by Marcia C. Inhorn and LuciaVolk.Description: New York: Berghahn Books, 2021. Series: Forced Migration; volume 40 Includes bibliographical references and index.Identifiers: LCCN 2021010857 (print) LCCN 2021010858 (ebook) ISBN9781800730564 (hardback) ISBN 9781800733695 (open access ebook)Subjects: LCSH: Refugees—Middle East—Social conditions. Middle Easterners—Relocation. Middle East—Emigration and immigration—Social aspects.Classification: LCC HV640.5.A6 U395 2021 (print) LCC HV640.5.A6 (ebook) DDC305.9/069140956—dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021010857LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021010858British Library Cataloguing in Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryISBN 978-1-80073-056-4 hardbackISBN 978-1-80073-369-5 open access ebookAn electronic version of this book is freely available thanks to the supportof libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborativeinitiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the publicgood. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Accessversion can be found at knowledgeunlatched.org.This work is published subject to a Creative Commons AttributionNoncommercial No Derivatives 4.0 License. The terms of the licensecan be found at For uses beyond those covered in the license contact Berghahn Books.This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

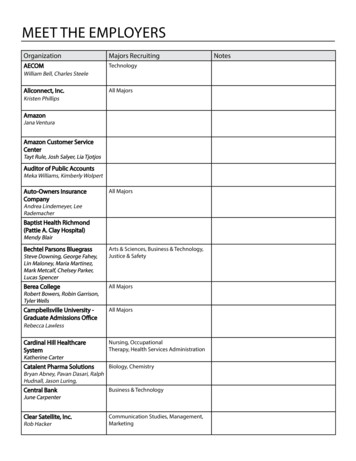

ContentsList of IllustrationsviiiAcknowledgmentsxIntroduction. Un-Settling Middle Eastern RefugeesLucia Volk and Marcia C. Inhorn1Part I. (Dis)Counting Refugees1. When States Need Refugees: Iraqi Kurdistan and theSecurity AlibiKali Rubaii252. Navigating Precarity, Prejudice, and “Return”: The (Un)Settlementof Displaced Afghans in Iran and AfghanistanNaysan Adlparvar403. Unsettling “Refugees” as a Category: Labeling, ImaginedPopulations, and Statistics in a Palestinian Refugee Campin BeirutGustavo Barbosa56Part II. Protesting Exclusion4. Middle Eastern Refugeehood in the Happiest Place on Earth:Syrians and Iraqis Entering Finland’s Welfare State BureaucracyLindsay A. Gifford695. “I Live Here; I Have a Right to Be Here”: An Afghan Refugee’sDisorientations and Insistence on Inclusion through TheaterJulie Nynne Bune88This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

vi Contents6. Demanding Their Welcome: Agency-in-Waiting at aProtest Camp in Dortmund, GermanyLucia Volk103Part III. Making Lives in Exile7. Living as Enduring: The Struggle for Life against the Limitsof Refuge among Gaza Refugees in JordanMichael Vicente Pérez1218. Reimagining “the Arab Way” in Exile: Futures “Off Line”among Syrian Men in AmmanEmilie Lund Mortensen1349. Proactive Reciprocity: Educational Trajectories Reclaimedthrough Patterns of Care among Refugee Men in GreeceÁrdís K. Ingvars147Part IV. Seeking Health10. America’s Wars and Iraqis’ Lives: Toxic Legacies, RefugeeVulnerabilities, and Regimes of Exclusion in the United StatesMarcia C. Inhorn11. Regimes of Exclusion in the Reproductive HealthcareSetting: Exploring Experiences of Syrian Refugees inSan Diego, CaliforniaMorgen Chalmiers12. Valuing Health, Negotiating Paradoxes: Medicalization of theHymen, Hymenoplasty, and Women’s Healthcare in OntarioVerena E. Kozmann163180196Part V. Reshaping Humanitarianism13. A Death Sentence? UNRWA in the Trump EraKhaldun Bshara14. Race, Religion, and Afghan Refugees’ Practices of Carein GreeceZareena A. Grewal213231This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

Contents vii15. Blurred Lines and Syrian Tea: Negotiations ofHumanitarian-Refugee Relationships in FranceRachel J. Farell24816. Inclusive Partnerships: Building Resilience Humanitarianismwith Syrian Refugee Youth in JordanCatherine Panter-Brick261Conclusion. Rethinking Exclusion and Inclusion inRefugee ResettlementMarcia C. Inhorn and Lucia Volk281Index290This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

IllustrationsFigures1.1. Picture of Kurdish President Masoud Barzani Passing througha Checkpoint.281.2. Feminist Kurdistan against ISIS.342.1. Number of Documented Afghan Refugees in Iran (1979–2019).434.1. Syrian Refugees Organize a Picnic at a Finnish Lakeside Park.756.1. Dortmund Protest Banner: “We Are Waiting to Be Grantedthe Right to Stay, While Our Families in Syria Are Waiting forDeath,” 2015.1128.1. Hani’s Drawing of His Life in Jordan, March 2018, Amman.14412.1. Different Forms of Biomedical Hymen PermeabilityCategories.20513.1. Banner in Ramallah: “UNRWA Remains a Living Testimonyfor the Catastrophe and Displacement of Our People in 1948.”November 2019.21713.2. Banner in Ramallah: “We Call upon the UN to Extend theMandate to Support and Protect UNRWA.” November 2019.21813.3. Street Artwork in Bethlehem Depicting the U.S. Withdrawalof Funds from UNRWA as a Crime against Humanity.April 2019.21913.4. U.S. Aid (in USD) to the West Bank and Gaza Strip(2008–19).22214.1. Painting of the Flag and Map of Afghanistan Foregroundedby a Cross.24316.1. “Do the Birds Need Passports to Enter Hungary?” Drawingfrom the Children’s Book Questions in a Suitcase by Abu Alhayat. 27016.2. “Where Do the Refugee-Giraffes Store Their Memories?”Drawing from the Children’s Book Questions in a Suitcase byAbu Alhayat.272This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

Illustrations16.3. Mural on the Wall of a Youth Center Hosting the AdvancingAdolescents Program. ix273Tables10.1. Iraqi Refugees Admitted to the United States (2007–15).10.2. U.S. States of Iraqi Resettlement (2006–15).13.1. Distribution of Palestinian Refugees around the Middle East(2014–18).13.2. U.S. Aid to Palestine (2008–19).13.3. Donations (USD) by Country and Percentage of UNRWA’sTotal Budget (2009–18).171172216224224This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

AcknowledgmentsIn a book devoted to the Middle Eastern refugee crisis, we must begin bythanking the many refugees from Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, and Syria whomade this book possible by sharing their lives and stories with us. Many ofthem have faced incredible hardships and unmitigated human suffering. Wededicate this book to them—hoping that they achieve the safety and settledfutures to which they ardently aspire.This book emerged from a meeting that took place at Yale University inSeptember 2019. The meeting brought together for the first time anthropologists studying Middle Eastern refugee populations in various Middle Eastern,European, and North American settings. Here, anthropologists were ableto discuss the ways in which war has led to refugee flight from the MiddleEast, and how resettlement in various host countries has unfolded. Theirwork, now published in this volume, speaks to the cultural, political, andlegal challenges that lead to regimes of exclusion in some settings, and regimes of inclusion in others. We are proud of and grateful to these dedicatedanthropologists, who are seeking to humanize the vitriolic discourses andpolitical debates surrounding Middle Eastern refugee resettlement in Europeand North America.At Yale University, our gathering was hosted by the Whitney and BettyMacMillan Center for International and Area Studies, the Council on Middle East Studies (CMES), and the Department of Anthropology. Generoussupport was received from the Edward J. and Dorothy Clark Kempf Memorial Fund, the Yale Program on Refugees, Forced Displacement, and Humanitarian Responses, and the U.S. Department of Education Title VI NationalResource Center, which supports Yale CMES’s activities. At CMES, we areparticularly grateful for the tireless organizational support of the CMES staff,including Cristin Siebert, CMES program director, and Marwa Khaboor,CMES program coordinator, who organized every detail of the meeting,from posters to travel to sound equipment and delicious halal meals. We alsoappreciate the support provided by the Yale Department of Anthropology,which, among other things, provided us with a beautiful weekend seminarThis open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

Acknowledgments xisetting in which to discuss our papers. There, Morgen Chalmiers and RachelFarell served as wonderful rapporteurs, providing detailed notes on our paper discussions.The meticulous professional copyediting of Bonnie Rose Schulman ensured that the book chapters came together seamlessly. We thank her immensely! Finally, we thank the excellent suggestions made by an anonymousreviewer and the dedicated editorial team of the Forced Migration Seriesat Berghahn Books. Special thanks go to Marion Berghahn, Tom Bonnington, Elizabeth Martinez, and Tony Mason, who strongly supported this bookfrom beginning to end.Alf alf shukran—a million thanks!—Marcia C. Inhorn and Lucia VolkNew Haven and San Francisco, January 2021This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

IntroductionUn-Settling Middle Eastern RefugeesLucia Volk and Marcia C. InhornThe first-ever Global Refugee Forum convened in Geneva on 16–18 December 2019, on the invitation of the United Nations High Commissionerfor Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nation’s main refugee agency (“UNUrges ‘Reboot’” 2019). Heads of state and international aid organizations,as well as business leaders, representatives of civil society organizations,and refugees met in Switzerland to discuss how to meet the needs of increasing numbers of forcibly displaced persons. All of the attendees agreed onthe severity of the problem, but there was no agreement on the amount ofaid needed and who was going to pay for and deliver it. While the GlobalRefugee Forum was in session, the Syrian government launched a renewedoffensive on its civilians in the country’s northern Idlib province, a militaryoperation that would lead to the displacement of more than 235,000 peopleby Christmas, most of them refugees from prior violence (British Broadcasting Corporation 2019).At the end of what UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandicalled this “decade of displacement” (UNHCR 2019), the world continuesto struggle to find ways to respond adequately to the humanitarian crisisin the Middle East, in a world where there are now more refugees thanat any time in modern history, including during World War II. It was inthe aftermath of that horrifying war—which saw unprecedented numbersof displaced persons—that world leaders first gathered in Geneva, Switzer-This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

2 Lucia Volk and Marcia C. Inhornland, to define the status of refugees. The goal of that convention—called the1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, or the1951 Refugee Convention for short—was to establish protections for persons“outside the country of their nationality” if they could provide evidencefor a “well-founded fear of being persecuted on grounds of race, religion,nationality, [or] membership of a particular social group of political opinion” (Gatrell 2013: 6). Not every member state of the United Nations signedthe resulting document. But those that did “agreed to the principle of nonrefoulement whereby no refugee could be returned to any country where heor she faced the threat of persecution or torture” (Gatrell 2013: 6).By international law, then, individuals who have crossed internationalborders as refugees have a right to protection from host states if returning totheir own states would harm them. However, the 1951 Refugee Conventionleft outside its mandate a very large group of forcibly displaced persons—namely, internally displaced persons (IDPs)—who fled their homes but didnot make it across any international borders. It also left unspecified whatforms of protection host states must provide to refugees. This lack of clarityhas generated a patchwork of largely inadequate refugee and asylum policies and practices in nation-states around the world.Furthermore, it is important to distinguish clearly between two termsthat are often used interchangeably in public debate: “refugees” versus“asylum seekers.” Every asylum seeker is a refugee, but not all refugeesbecome asylum seekers (Gibney 2004: 5–11). For asylum to be claimed, aperson must be near or inside the border of the country where an asylumpetition will be lodged. Most of the world’s refugees remain in countriesclose to the ones they left, waiting to return to their homes once the conditions that forced them to flee cease to exist. But more and more personsnow travel from their home countries to Europe and North America toask for asylum there, and “it is the growth in asylum seekers that has, overthe last thirty years, made refugees such a burning political issue” (Gibney2004: 9). Put differently, asylum seekers are refugees at Europe’s and NorthAmerica’s doorstep.Middle Eastern RefugeesThis book focuses specifically on Middle Eastern refugees. “Middle Eastern” here refers to individuals residing in the geographical area from Egyptin the west to Afghanistan in the east.1 While aware of the problematic colonial legacy of the term “Middle East” and the existence of other maps ofthe region that also feature, for example, the countries of North Africa (Volk2015: 13–16), we use “Middle Eastern” here as an umbrella term that comprises the region’s countries most affected by war and forced displacement.This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

Introduction 3Unfortunately, the Middle East is a region with a well-documented history of forced displacement from the time of the Ottoman Empire untiltoday (Chatty 2010; Gelvin 2015). In that sense, the topic of Middle Easternrefugees is not new. Looking at the historical record, it becomes clear thatMiddle Eastern refugees do not come out of nowhere: they have been produced by wars in the Middle East (Inhorn 2018), which have led to deathand destruction, various forms of physical and structural violence, precarious economic and social conditions, and dysfunctional and highly volatilepolitical environments.Indeed, no other region of the world has suffered so much war, turmoil,and population disruption due to protracted conflict than the Middle East(Mowafi 2011). Conflicts dating back to the end of World War II can betraced to six critical forces. First was the founding of the state of Israel in1948, which resulted in an ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine, aswell as a series of wars between Israel and neighboring Arab nations. Thesecond cause was colonial independence movements, especially against theFrench but also the British, which led to wars of independence. Third weresectarian-inflected battles, such as the civil war in Lebanon and the eightyear Iran-Iraq War, launched by Saddam Hussein and his secular Baathregime against the Shia theocracy that came to power in Iran in 1979. Afourth factor was thus the rise of Islamist movements in the region, whichled to wars between the more secular and Islamist forces. Fifth was the ColdWar between the United States and the Soviet Union, which has played outin the Middle East in ways that continue to haunt the region, particularlyin Afghanistan. Finally, the 2011 Arab uprisings—which began as peacefulprotest movements to gain greater political freedom, economic prosperity,and human dignity—descended into military repression and turmoil in several countries and erupted into the most bloody war in the country of Syria.These various wars have created the Middle Eastern refugees who arethe focus of this book—namely, Afghans, Iraqis, Palestinians, and Syrians.Over the past decade, they have been the nationalities with the dubious distinction of rising to the top of the UNHCR charts. Chronologically speaking, Palestinians are the nationality with the longest history of displacement,beginning in 1948 with the founding of the state of Israel. Approximately750,000 Palestinians became refugees as a result of the 1948 war, and nonewere allowed to return to the homes or communities from which they weredisplaced. Thus, today, more than 7 million Palestinian refugees live scattered around the world, with more than 1.5 million of them in refugee campswithin the Middle East.Afghans began leaving their homeland in large numbers with the beginning of the Soviet invasion in 1979. Due to subsequent wars—including theUnited States’ war in Afghanistan, which began in 2001 after the September11 terrorist attacks, and has continued for two decades—Afghans have beenThis open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

4 Lucia Volk and Marcia C. Inhornforced to flee, primarily to neighboring Iran or Pakistan, in search of safetyand stability. Iraqis, too, have experienced two US military interventions:the first Gulf War in 1991, which lasted seven months, and the second IraqWar in 2003, which officially ended nine years later in December 2011, butwhich has lasted well beyond in terms of violence and troops on the ground.Both of these Iraq wars have produced large numbers of refugees and IDPs.In 2011, in response to popular protests, the Syrian government beganattacking its own citizens, leading to a decade-long war that has been fueled by support from foreign governments, including those of Iran, Russia,Turkey, the Arab Gulf states, and the United States. The many front linesin Syria have been shifting over the past decade, also spilling over into theKurdish sections of southern Turkey. Moreover, in parts of eastern Syria, Islamist militias used the resultant power vacuum to attempt to establish theiridea of an Islamic State. Targeted by Syrian government, militia, Islamist,and external military forces, more than half of Syria’s population has become displaced. Half of these forcibly displaced persons have fled the country as refugees, while the other half remain as IDPs inside Syria’s borders.Today, Middle Easterners make up the majority of the nearly 80 millionforcibly displaced persons. This is double the number seen twenty yearsago (UNHCR 2020). Of the world’s 26 million refugees—20.4 million ofthem registered with the United Nations—the largest population consists ofPalestinians, 5.6 million of whom have lived since 1948 under the mandateof the second largest UN refugee agency, the United Nations Relief andWorks Agency (UNRWA). Syrians now comprise the largest newly createdrefugee population, with nearly 6.6 million refugees, and 6.2 million IDPsin need of humanitarian assistance (UNHCR 2020). Afghanistan currentlyplaces third on the UNHCR’s list of globally displaced persons, with 2.7million Afghans registered with the United Nations despite not having formal refugee status in the neighboring host countries of Iran and Pakistan(UNHCR 2020). Iraq has among the highest number of new IDPs, morethan 3 million since 2014, and 6.5 million in need of humanitarian assistance(UNHCR 2020). Adding up these numbers, Middle Eastern refugees currently make up more than half of the world’s total refugee population. As aregion, the Middle East has more IDPs than any other.Regimes of Exclusion and InclusionIt is important to remember that refugees do not choose to be uprooted;somebody with control over deadly force displaces them. Historically, Germany created the largest number of refugees during World War II. As aresult, Germany today sees refugee resettlement as a moral and political responsibility. Even though Germany did not cause any of the deadly conflictsThis open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

Introduction 5that have led to their displacement, the country has taken in more MiddleEastern refugees than any other European country (Bock and Macdonald2019: 13; Volk, this volume). Germany and Finland—both strong Europeanwelfare states—grant foreign nationals rights in their respective constitutions(Bock and Macdonald 2019; Gifford, this volume). While it can be debatedwhether Germany and Finland live up to the actual spirit or just the letterof their laws, granting a certain set of rights to noncitizens via a nationalconstitution has been an important step for these states in promoting a moreinclusive national community. It is important to remember that the UnitedNations may be the source of most human rights legislation, but it is nationstates that must implement and enforce them, thereby creating viable andwelcoming regimes of refugee inclusion.Unfortunately, as of 2018, less than 5 percent of refugees identified byUNHCR were resettled—or a mere 0.2 percent of the global refugee population (Baldoumas, van Roemburg, and Truscott 2019). Although some European states, such as France, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom,have taken in considerable numbers of Middle Eastern refugees, they havestill been criticized for failing to take in their “fair share” (Baldoumas, vanRoemburg, and Truscott 2019), while the underresourced Mediterraneannation of Greece continues to be overwhelmed with boatloads of newlyarriving refugees (Grewal, this volume; Ingvars, this volume), many ofthem housed in deplorable conditions on the Greek islands. Unfortunately,Greece’s appeal to share the refugee burden with other EU states has fallenon deaf ears. Indeed, many of the wealthier European states, such as Denmark and Norway in Scandinavia, have chosen to turn away Middle Eastern refugees at their doorsteps (Bune, this volume; Gifford, this volume).Increasingly, right-wing governments have come to power in many WesternEuropean nations by promulgating anti-immigrant rhetoric grounded inIslamophobia and rationalized by threats of terrorism.Unfortunately, the United States—a country once known for its refugeeinclusion, particularly in the aftermath of its twenty-year military intervention in Vietnam—has become one of the most profoundly exclusionary regimes in the world. On 1 November 2019, U.S. president Donald Trumpcapped the number of Iraqis eligible for priority admission, even thoughmost had served with U.S. troops in Iraq. Despite an estimated 110,000 applications at various stages of the approval process ( Jakes 2019), only 4,000special immigrant visas (SIVs) were granted for Iraqi men who had servedas aids and interpreters for U.S. forces and faced a “well-founded fear ofbeing persecuted” in their home country. The United States is a signatoryto the 1967 UN Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees—which universalized the 1951 Refugee Convention by dropping references to “Europeanrefugees” in the context of World War II. But during the Trump presidency,the United States no longer lived up to its moral obligations to protect thoseThis open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

6 Lucia Volk and Marcia C. Inhornwho had been displaced, particularly through America’s own wars in Iraqand Afghanistan (Inhorn, this volume).At the same time, countries that did not sign the 1951 Convention orthe 1967 Protocol now host some of the largest numbers of refugees. Forinstance, the relatively small Middle Eastern nation-states of Jordan andLebanon have received large numbers of Palestinian refugees over manyyears (Barbosa, this volume; Pérez, this volume). In recent years, both countries have also taken in millions of Iraqis and Syrians. Turkey is currentlynumber one on the UNHCR refugee host country list, with more than 3.6million Syrian nationals now living on Turkish soil. Ironically, Turkey is asignatory to the 1951 Convention, but it never signed the 1967 Protocol,which means that it officially grants refugee protections “only to Europeans”(Chatty 2018: 230).Turkey, a non-Arab Middle Eastern nation, has taken in the largestnumber of Arab refugees from Syria, throwing into question the moral andpolitical responsibility of the wealthy Arab Gulf states to aid in Syrian resettlement. As of this writing, it is also important to note that the Arab Gulf iswitnessing the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, with Saudi Arabia leadinga nine-state coalition in a devastating war against Yemen. The UNHCR(2019) estimates that 24 million Yemenis, or 80 percent of the total population, are in need of some form of humanitarian assistance. Two out of threeYemenis are unable to afford food, and half of the country is on the brink ofstarvation. One million cholera cases have occurred in Yemen since 2018,25 percent among children, making this the largest cholera epidemic in theworld. Yet the military and public health crisis in Yemen has received littlemedia or scholarly attention, prompting the question, Does anyone careabout this new population of forcibly displaced Middle Easterners?Scholarly Perspectives on Un-Settling RefugeesAlthough the UNHCR continues to report record-breaking numbers offorcibly displaced Middle Eastern people, global media attention to the refugee crisis has waned. Such attention was at its peak in 2015, when boatloads of Middle Eastern refugees began washing up, both dead and alive, onEurope’s shores. It was at that point that scholarly attention to Middle Eastrefugees began to gain significant traction, with researchers entering the hostcommunities to which vulnerable populations had fled.Two disciplines in particular took interest in the Middle Eastern refugeecrisis. The first is the discipline of international relations (IR), one of thesubfields of political science. Since refugees cross nation-state borders, andtherefore subvert, undermine, or challenge state sovereignty—a core principle of the international order established by the Treaty of Westphalia inThis open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.

Introduction 71648—refugees, by default, become a security threat to that order. Moreover, since international governmental and nongovernmental organizations(NGOs), such as the United Nations, the International Red Cross, or theInternational Organization for Migration, handle many of the bureaucraticand logistical responsibilities for individuals who find themselves displaced,most IR classes that

Un-Settling Middle Eastern Refugees REGIMES OF EXCLUSION AND INCLUSION IN THE MIDDLE EAST, EUROPE, AND NORTH AMERICA Edited by Marcia C. Inhorn and Lucia Volk berghahn N E W Y O R K † O X F O R D www.berghahnbooks.com This open access edition has been made available under a CC B