Transcription

News for Schools from the Smithsonian Institution. Office of Elementary and Secondary Education. Washington, D.C. 20560October 1991The Survival Game after Columbus:Pigs, Weeds, and Other PlayersAt the beginning of 1492, the Old World and theNew had been cut off from each other forapproximately 10,000 years. Now this separation wasabout to end.For weeks, three small Spanish ships had beenventuring farther from Europe into the unchartedwaters of the western Atlantic, through unfamiliarwinds and unknown currents. No one on board waseven positive that there was land out there. Columbushimself, the leader of the expedition, had beendeliberately under-reporting the distances traveledeach day, in an effort to assuage his sailors' anxiety.Even so their fear of the unknown was bringing themto the edge of mutiny.Then, on the evening of October 11, land wassighted-the Bahamas (though those on shipboardthought they were seeing Asia).The next day, a party of Europeans stepped ashoreonto American soil . establishing a contactbetween Old World and New that has continued tothis.day.There was no way that these people couldpossibly have guessed what massive trains of causeand effect they were setting in motion-trains ofcause and effect that today are still shaping our lives.What happens when living creatures from twoworlds that have been evolving separately for 10,000years are suddenly thrown together?It was as if the wall separating* two rooms stuffedfull of living creatures had been torn open. Creaturesfrom both rooms began to pour through the opening,bumping into each other, attacking, fighting back,competing, eating, being eaten, struggling to findfood and living space and safety in a scheme ofthings that was suddenly completely different.Even while the Europeans and the Indians wereexamining each other with amazement and strugglingto exchange thoughts without a commonlanguage . . . biological exchanges were proceedingfast.Microorganisms from European lungs were beingbreathed out into the New World air . and beingsucked into Indian lungs. Seeds stuck to Spanishboots were being scraped off and ground intoAmerican soil. Soon American foods would beentering European stomachs, and Indians would besampling European foods the Spaniards offered.European body wastes, along with the bacteria andparasites they contained, would be deposited on NewWorld soil. Spaniards would be packing up samplesof American plants and animals, and kidnappingsome Indians, to show off back in Spain.And this was just the beginning of an endlessstream offurther arrivals from the Old World: humanbeings, dogs, pigs, horses, cattle, food plants, grapecuttings, fruit pits, olive trees . and more and morevarieties of unwittingly carried seeds and spores andgerms.But before going on with this story, let's leave thisscene and set up an analogy that can help yourstudents focus on some biological essentials of theupheavals that Columbus was setting in motion.(Please stop here and read "The Game ofSurvival," on the Pull-Out Page. Then continue withthis Teacher's Background.)Since ourspace is limited, we can discuss only afew examples in this ART TO ZOO. We have chosenones that suggest parallels that your students candiscuss . . . and that illustrate ecological principlesthat have vital implications for us today.Unloading Old World items onto New World soil. This ART TO ZOO describes what happened to some of theliving freight-including hoofed livestock like the pigs, cattle, sheep, and horses in the foreground of this picture.Livestock ColonizersHuman beings and their livestock (pigs and cattlewill be our main focus here) had been living close toeach other and depending on each other forthousands of years in the Old World. People there ledtheir herds to pasture, provided water and winterfodder, set shepherds to guard flocks againstpredators, and provided barnyard shelter whennecessary.For these human populations, taking care of theirlivestock was a move that paid off: the livestockplayed a vital role in helping the human beingssurvive. People ate their animals' meat, drank theirmilk, wrapped themselves in their hides, rode ontheir backs, and used their musclepower to haul theirplows and carts and carriages.Naturally, when Europeans came to the NewWorld, they brought livestock with them.What happened to these Old World animals whenthey were set down in the New World-where thegame had developed with different players, into adifferent set-up?Most domesticated animals from the Old Worlddid well in the New. They multiplied dramatically,spreading into more and more regions. Some ran offand flourished in the wild.Pigs followed this pattern the soonest and fastest.They were ideal colonists-tough, omnivorous, andprolific. They gorged themselves on the abundantfruits and nuts of the Antilles, where they were firstset down, and began producing three litters a year.Soon more and more pigs were eating their wayacross more and more New World areas: gobblingnuts and fruits, gouging up roots, ripping outplants.Cattle too raised havoc in their new surroundings,as they ate and trampled their way throughpopulations of native plants unadapted to abuse onthis scale. It wasn't many years before herds hadestablished themselves up and down the Americas.When these and other Old World hoofed farmanimals stepped onto New World soil after crossingthe Atlantic, they were entering a world that had beenproceeding along different lines from back home.These animals thrived in their new surroundingsbecause, in the main, they found there ample food,few competitors, few predators, and few diseases towhich they were susceptible.The contrasting histories of the Old and NewWorlds provide some clues to why this was so.In the Old World, where hoofed grazers (bothdomesticated and wild) were numerous, wholenetworks of players had evolved together. Thevarious species developed ways of surviving in each. others' presence. . . and even of using each others'presence as their means of surviving. Germs andworms evolved that could use grazing mammals ashosts. Predators were drawn to places wherelivestock offered easy prey: wolves stole lambs fromflocks; foxes stole chickens from barnyards. Andplant species that evolved in ways that allowed themto survive and reproduce even after being trampled*Actually. the separation was not total. More about this later.Continued on page 2

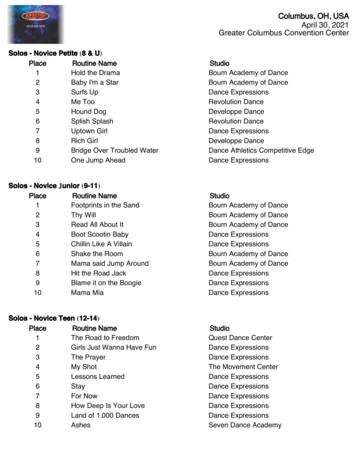

continued from page 1and gnawed gained a competitive edge.The New World was a different story. AmericanIndians were superb plant growers, but they had fewdomesticated animals: some dogs, guinea pigs; a fewkinds of fowl; and, in the Andes, llamas and alpacas.Large wild herds of hoofed grazers were alsouncommon in the parts of the New World where theSpanish settled early on.*This situation made for different developments.Here in the New World, parasites were adapted toNew World animals, not to the Old World grazers.Here, most plant populations were not particularlywell equipped for surviving heavy onslaughts fromanimals, because until the spread of Europeanlivestock, to do so had offered no particular survivaladvantage. And here there were few predators able toprey on animals as large and tough as these Europeanpigs and cattle.This situation gave the Old World animals anopening in the game-and they were quick to takeadvantage of it. But winning moves by some playersspell losses for others.The proliferation of Old World livestock in theAmericas made survival harder, or even impossible,for many of the native American plants and peoples.As Old World cattle, pigs, and horses spread acrossAmerican landscapes, they packed down the soil withtheir hooves, crushed plants underfoot, gnawed downplants. . . . Result: in place after place, native plantpopulations were snuffed out.The spread of Old World livestock made survivalharder for native people too. Plant foods were themainstay of most Indians' diets. As the herds grew,local humans found themselves competing with thelivestock (especially with pigs) for wild plant foodsthat both ate. Meanwhile, the Europeans were turningmore and more land into pasture. Often this meantthat the Indians could not even count on harvestingthe produce they planted in the gardens they wereable to hold onto-because livestock from nearby,usually unfenced, pastureland were apt to wander in,trampling and consuming the crops.But the game-the environment-never standsstill. As the years passed, the livestock lost some oftheir initial advantages. Most important, thesenewcomer animals began in many places to eat theirway through their food supply. The animals' initialpopulation explosion usually lasted only a fewdecades in any area.Take cattle in what is now Mexico, for example.They were introduced for breeding purposes in 1521.At first there were so few that killing any wasforbidden. But within just a few years, the cattle weredoing so well that cattle ranches were springing upall around. When the cattle spread into the richgrasslands in the northern part of the country, theirrate of increase soared even higher. One writer notedin 1579 that a herd of 20,000 was considered small inthese parts, and some ranches had as many as150,000. (Back in Spain, herds of over 1,000 wererare.) Yet by the late 1500s, large areas of centralMexico had been so overgrazed that cattle in someplaces were starving to death. The great herds beganto shrink.Plant ColonizersFor Old World people and their animals, moving tothe New World created opportunities to prosper. Butthey were not the only newcomers for whom themove was advantageous: Old World plants too weresoon spreading over the Americas.Some of these plants were brought over onpurpose, as the livestock were, by Spanish colonistseager to have a local supply of the foods they wereused to. The Americas offered variety enough inclimates and soils so almost any European crop couldfind a place there to flourish. It wasn't long beforeSpaniards in the New World were eating bread madefrom American-grown wheat with olives fromAmerican-grown trees, washed down with winepressed from American-grown grapes-even thoughnone of these food plants had existed in the Americasbefore.In addition to these and countless other Old Worldfood plants that were brought over and cultivated,numerous wild Old World plants-weeds-came tothe New World and flourished. When the Europeanlivestock munched and trampled populations ofnative plants out of existence, it was very often OldWorld plants that moved in to replace them. In theWest Indies, Old World thistles, nettles, and sedgeswere proliferating by the early l500s. In Peru,European clover spread so aggressively that itsmothered out native crops in many areas. And bythe end of the century, the weed population of centralMexico was made up mostly of Eurasian plants."Farther north, in wh'i-t are now the United States and Canada, there werehuge herds of buffalo.2.0' '"; :lIIl. ' " . . - '* : :' «- ' - "'i!f 5:; Horses being loaded for transport to the New World. On board ship, horses were often held in slings to keepthem from falling. Nevertheless, as many as half died during the ocean crossing. In the New World, horses wereslower to establish themselves than were pigs or cattle. The tropical lowlands where they were first introducedwere not well suited to them. Once they reached temperate grassland areas, they multiplied rapidly.Why was it that Old World plants-rather thanindigenous New World ones-so often moved inwhen local plant populations were destroyed?To get some inkling of possible reasons, it'snecessary first to think about what weeds are.Weed is not a scientific term. It's what people callplants they consider "useless" or don't want around.What is thought of as a weed in one place may becultivated deliberately elsewhere. For instance, theclover that ran wild in parts of Peru, stiflingindigenous competitors including Indian crops, inother times and places is raised to provide forage,prevent erosion, and put nutrients back into the soil.Weeds grow exuberantly under what would seemto be the worst of conditions-in habitats that havebeen deeply disturbed: plowed up, burnt over,flooded out. Weeds can thrive in the scorchingsunlight of stripped spaces. They grow fast. Theypropagate under conditions that kill off lessaggressive species. Weeds often possess several waysof propagating: by means of shoots, for instance, bitsof root, bulbs, runners that snake out over the ground,or seeds that can survive passage through an animal'sdigestive system and then invade a new territory bysprouting wherever they emerge.Back in Europe, there were plenty of disturbedareas where these qualities were called for. Forthousands of years there, herds of animals had beentrampling and munching, and human beings had beenplowing up fields, clearing forests, and buildingroads and towns. Where such conditions prevailed, itwas the plants with weedy resilience that bestsurvived . and by competing with each other overthe centuries, they became even better at flourishingin adversity.New World conditions were quite different. Fewerpeople, as well as fewer grazing mammals, livedthere. Estimates of the total human population of theAmericas at the beginning of 1492 vary widely, butaround 100 million people would be in thereasonable range. At the same time, the Old Worldpopulation was probably approaching 600 million.In other words (since the Americas together coverhalf the area of Europe, Asia, and Africa together)the New World had on average one-third the OldWorld's population density*-one-third the numberof people per square mile, on average, to tear up their"Throughout most of the New World's history, its population had beensmaller and more widely scattered. But in the last thousand years or sobefore Columbus, thickly populated areas had been developing in parts ofwhat are now Mex.ico and Peru, and to some degree in Central America.Teotihuacan, in Central Mexico, was by 500 A.D. probably the six.th largestcity in the world, with about 200,000 inhabitants.By 1492, well over half of the people in the Americas were clustered inthese built-up areas; the rest were scattered thinly over the huge remainingportions of the American continents.surroundings. Moreover, New World people hadlifestyles that tended to be less destructive of theirenvironments than the lifestyles of Old Worldpeople.American Indians, for example, used diggingsticks and hoes-far less invasive agricultural toolsthan the European plows, which could churn upwhole fields.With the arrival of the Europeans, this changed.Wherever they settled, these human newcomerscreated upheavals in their surroundings. They burnedand cut down forests, plowed up land, set looselivestock, dug mines.In short, they created just the kinds of conditionsthat Old World weeds were particularly well adaptedto taking advantage of. Transported to the Americas,these plants moved quickly, making the most of asuperb opening in the game.Germ ColonizersIn the years after the two worlds came into contact,epidemic after epidemic of Old World diseases struckdown staggering numbers of Indians. Over and over,on down into our own century, whenever formerlyisolated New World populations have come intocontact with Old World people, Old World diseaseshave taken heavy tolls.These Old World diseases spread for many of thesame reasons that Old World livestock and OldWorld weeds spread: thrust into the New World, theyfound themselves in surroundings that offered plentyof food and few enemies-surroundings suited to adifferent combination of players.To understand why Old World diseases struck theway they did, it is necessary to think about the factthat germs (like livestock and weeds) are livingcreatures. Like all living creatures, they have to findthe resources they need or they will die. They tooplay the game.From people's point of view, the germs that infectthem with a serious disease are a threat. But from thegerms' point of view, the people are anopportunity-a place to live, an environment that canprovide food and shelter.For a population of germs and a population ofhosts (people are the host species we are talkingabout here) to keep living in the same geographicalarea, they have to reach some kind of balance.Otherwise, one or both of the populations will dieout:"The antibodies that a baby can receive from its mother for a short whileare an exception.

If the people are too resistant to the germs, thegerms won't be able to successfully take up residence. and will die out. If the people are so vulnerable that everyonewho is infected immediately dies, then bothpopulations will probably disappear: first the peoplewill die of the disease; then the germs will diebecause there are no more hosts left to live in.One way that human beings defend themselvesagainst invasions by populations of germs is byproducing antibodies-special molecules that destroya particular species of germ.Nowadays, inoculations can induce people toproduce antibodies to diseases they have neverencountered naturally. But this is a new development,and one limited to certain diseases. In the past, aperson had to be naturally exposed to a disease-thegerms producing that disease had to actually invadethe person's body-before the person could produceantibodies to that disease.:I If a particular kind ofgerm had never been around, then people had noantibodies to protect them against it.From the germs' point of view, then, moving intoa new geographical area can be an excellent move.When germs come across a human populationwithout antibodies to them, it is like a burglar comingacross a town without locks.Of course, soon the townspeople will order locksand the people exposed to the germs will begin toproduce antibodies to them. For this reason, thegerms' move helps them most early on.Now let's look at how this actually happened withone particular disease-smallpox.Smallpox. Smallpox was probably the firstmassive epidemic of an Old World disease to occurin the Americas. It arrived in 1518, when it landed onHispaniola (the island that today comprises Haiti andthe Dominican Republic) and wiped out all but athousand of the Indians living there.Then it advanced like fire across the Americas.Wherever the smallpox germs went, most Indianscame down with the disease, and somewherebetween one-third and one-half of those who caughtit died. In Mexico, smallpox struck just as the AztecIndians were preparing to attack the small band ofSpanish invaders. In Peru a few years later, it killedoff-among countless other victims-both the Incaleader and his successor within just a few hours,leaving the indigenous government in disarray.The Spaniards, meanwhile, remained untouched.To both Spaniards and Indians, it must have seemedthat heaven had turned its back on the nativeAmerican peoples.Even places that Europeans never visited directlycould export germs-for a disease could spread fromperson to person along trade routes.Diseases from all over the Old World thrived inEurope, especially in large ports, where crowdingand poor sanitation created ideal conditions for thespread of illness. Smallpox, typhus, measles, andother diseases kept permanent residence in suchplaces. Virtually all city dwellers who survived toadulthood had become immune. Yet the germscausing the illnesses did not die out, because therewere always enough children being born so thegerms could find vulnerable hosts.New World. Circumstances in the Americas rightbefore Columbus were very different-and,unfortunately, perfectly suited to maximize thespread of imported diseases. Isolation had prevented the development ofimmunities. Since the Americas had been cut offfrom the rest of the world for about 10,000 years, theIndians had had no chance to develop immunities toforeign germs. The Bering "decontamination chamber." Whatabout the germs that the original Americans broughtwith them when they crossed over from Asia? Didn'tthey bring Asian (Old World) germs?Probably far fewer than if they had crossed intothe Americas through a milder area. The cold in theBering land bridge area probably killed off a lot ofthe germs that the immigrants carried. Their bodieshad already produced antibodies, and only healthypeople were likely to have survived the rigors of thetrip. The first New World peoples probably enteredthe Americas relatively disease-free. Low population density in past. Moreover,during most of their history, New World peopleswere spread out thinly, making large-scale epidemicsunlikely. Where there are no nearby hosts to infect,populations of germs tend to die out. Recent rises in population density. However, aswe have seen, areas of dense human population haddeveloped during the last centuries before Columbus.The Indians in these regions had lost the protection oflow population density; here there were plenty ofpeople to fuel any epidemic that might start. Absence of domesticated herds. Some OldWorId germs that infected people passed part of theirlife cycle in animal hosts, particularly in thedomesticated animals that were so common there.The relatively small number of domesticated speciesand the absence of large herds in the New WorIdtended to make this an ineffective play in the NewWorld.disease; etc.)Finally, say that pigs were just one of many, manyspecies of living creatures from Europe and Asia andAfrica that were brought to the Americas after 1492.Among the other animals deliberately exported werecattle, horses, sheep, goats, and dogs. Inadvertentexports included Old World rats and many plantweed species.(Step 2: Worlds Apart, Worlds TogetherProvide each of your students with an outline map ofthe world. Have them write in the names of thecontinents. (Antarctica may be omitted.)Then ask: Are there places where the continentsare joined, or are they completely separate? Thechildren can see for themselves that the inhabitablecontinents are clumped into three separate chunks: Europe and Asia are really part of the same hugeland mass, which is joined to Africa by the part ofEgypt where the Suez Canal is. These threecontinents together form the Old WorId. North and South America are joined, andtogether form the so-called New World (new, that is,to the Europeans who sailed there). Australia is by itself. (We won't be talkingabout it in this ART TO ZOO.)Have the kids fill in the Old World and the NewWorld on their maps, each with a different color, andlabel the two areas. Be sure the children understandclearly the meaning of the terms Old World and NewWorld, since they will be used over and over in thisART TO ZOO.Tell the class that human beings evolved in theOld World (probably in Africa). No one knowsexactly when these first people arrived on the scene(the date depends also on which of our ancestors youcount as people) . but humans could very likelyhave been living in the Old World well over a millionyears ago.Meanwhile, during most of these million-plusyears, there wasn't a single human being in the NewWorld. There were lots of other living creaturesthere-whose ancestors had been alive when thecontinents were still joined into a single land mass.But the earliest human beings appeared after thecontinents had moved away from each other: theyhad no way to cross over to the New World.Then, during the most recent Ice Age, the level ofoceans dropped worldwide . and a land bridgebetween Asia and North America emerged at theBering Straits. (Have your students locate and markthis place on their maps.)Over this land bridge came people in search offood-the Asians whose descendants became theEskimos and Indians ofthe New World.Then, about 10,000 years ago, the Ice Age ended,the oceans rose, and once more the Bering Straitsland bridge disappeared underwater (where itremains today). Once again, the Old World and theNew were cut off from each other. They remained sofor about 10,000 years.This isolation was not total. Occasional shipsblown off-course during storms, for example--oncein a while made their way from the Old World to theNew. Some ships probably made the crossingintentionally. The Vikings even established a colonyin North America in the 11th century. But it didn'tlast long. This and these other pre-Columbiancontacts seem to have had no significant impact.Not until Columbus arrived in 1492 was ongoingcontact established.Step 3: The Game of SurvivalWhat happened then, when living creatures that hadbeen evolving in two separate worlds for thousandsof years, came into ongoing contact? Beforebeginning to find out, your students should read "TheGame of Survival," on the Pull-Out Page.Then give them plenty of time to ask questionsand discuss what they have read. Emphasize howinterrelated every part of an environment is in thisgame: if one population makes a move, it changes theset-up of the game for other populations around it.Diseases seemed to single out New World victims.They also seemed to travel from Old World to New,but seldom in the opposite direction. * Why? Onceagain, the very different circumstances in which Oldand New World peoples had been living can helpexplain these contrasts.Old World. Long before Columbus, ically cosmopolitan. With tradeconnections reaching all the way across Asia,through the Middle East, and into Africa, Europeanshad for centuries been importing exotic germs alongwith exotic goods.*The only major human disease that may have traveled from New World toOld is syphilis. which first appeared in Europe around 1500. But there is noconsensus about its origin.Lesson PlanStep 1: How Many Pigs?Begin by having your students carry out the "HowMany Pigs?" activity on the Pull-Out Page, ashomework.In class the next day, after the children havechecked their answers, give them a chance to discussthe activity. Do they think the pig population wouldactually get this large in real life? Why not?With your guidance, the children should be able tofigure out for themselves many of the factors thatwould in reality keep the actual number of pigs farsmaller. (Lack of food, of water, of space, of hidingplaces; competing species; attacks by predators;Step 4: Animals, Plants, GermsNow draw on the "Animal Colonizers," "PlantColonizers," and "Germ Colonizers" sections of theTeacher's Background to describe some examples ofbiological consequences of the contact thatColumbus initiated.Guide the children to see the parallels between theanimal, plant, and germ examples: In all three cases,when the newcomers that are described arrived in theNew World, they found abundant sources of food .and environments where, at first, local species werenot able to make the kind of moves that would slowthe newcomers' spread.Continued on page 43

continued from page 3After the children have had plenty of opportunityfor discussion, have them conclude this section bywriting the "Weird Postcard" on the Pull-Out Page.You can end the Lesson Plan here if you are out oftime. Or you can develop these ideas further bymoving on to Step 5.Step 5: Human Population GrowthNow that your students have looked into severalexamples of fast-growing populations, you may wantto have them conclude by turning to the humanpopulation, which began its dramatic upswing around1650-in part because food plants of New Worldorigin (most notably potatoes and com) dramaticallyincreased the food supply worldwide.Here are some approximate world population figures4000 B.C.I A.D.1000 A.D.1650 A.D.1750 A.D.1850 A.D.1950 A.D.1970 A.D.1990 A.D.2000 A.D.15 million250 million340 million500 million711 million1,130 million2,500 million3,650 million5,300 million6,250 million (estimated)First, have your students make a graph of thesefigures. Then ask them to write a short story aboutwhat they think might happen in the future becauseof this human population growth. Ask them to createtwo or three alternative endings for their story, and todescribe what events took place to cause thesedifferent outcomes.National Metric WeekOver 95 percent of the world uses the metricsystem of measure, yet many Americans arestill inching along with our traditionalsystems. Use of metrics is not mandatory inthe United States, but more and morebusinesses are converting to stay competitivein international markets.To obtain a kit of useful posters, handouts,cards, and explanatory materials to use withyour students write toMetric Program OfficeU.S. Department of Commerce, Room 4845Washington, D.C. 20230. and celebrate National Metric Week,October 6-12, 1991!Howard Hughes's airplane, in which he flew around the world in 1938. His trip took 4 days: the linkage ofOld World and New had become much faster than in Columbus's time . and the population of both worldsmuch larger.Seeds of ChangeBibliographyThe exhibition Seeds of Change, at theSmithsonian's National Museum of NaturalHistory from October 26, 1991 until April 1,1993, examines the exchange of plants andseeds between the Old and New Worldsfollowing Columbus's arrival in theAmericas in 1492. Themes include theeffects of the introduction of potatoes andcom to the New World.A traveling version of this show, organizedby the Smithsonian Institution TravelingExhibition Service (SITES), will be ondisplay in cities around the United States.For information, contact:Books for TeachersOffice of Public AffairsSmithsonian InstitutionWashington, D.C. 20560TeL (202) 357-2627.Other SmithsonianQuincentenary ActivitiesFor information about other Smithsonianevents commemorating the 500th anniversaryof the landing of Christopher Columbus inthe New World, contact:Office of Quincentenary ProgramsSmithsonian Institution1100 Jefferson Drive, Suite 3123Washington, D.C. 20560Tel. (202) 357-4790.Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Exchange:Biological and Cultural Consequences of1492. Westport, Connecticut: GreenwoodPress, 1972. Ecological Imperialism: TheBiological Expansion ofEurope, 900-1900.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,1986.McNeill, William H. Plagues and Peopl

The Survival Game after Columbus: Pigs, Weeds, and Other Players Unloading Old World items onto New World soil. This ART TO ZOO describes what happened to some of the living freight-includinghoofed livestock like the pigs, cattle, sheep, and horses in the foreground of this

![[ST] Survival Analysis - Stata](/img/33/st.jpg)