Transcription

Essential Techniques forBending WoodPlus a Bent Wood Shelf Plan

Photo by Al Parrish

Most of the time when apiece of wood has a bendor a curve, it means trouble: Your stock is warped or bowed.But sometimes a bent part can addan interesting design element. Thecurved supports in these shelvestransform what might be plainand ordinary into an interestingand contemporary design.I usually like to keep thingssimple, which to me means usingas few parts as possible. But when itcomes to curved parts, such as thesupports for these shelves, I formthe curves by gluing together several thin strips rather than steambending one piece of wood. Thistechnique of bent lamination isfaster and the results are morepredictable than steam bending.With steam bending, you needa boiler, a steam box and a wayto quickly clamp a scalding-hotpiece of wood to a form. Then youneed to wait several days for thepart to dry. With bent laminationyou need only a form and a way toclamp the thin strips of wood to it.You don’t need to wait an hour ormore for the wood to get ready tobend and you don’t need to racelike a madman to get a hot piece ofwood clamped in place. Once theglue is thoroughly dry, the partsare ready to use.The techniques I used to buildthese shelves can be employedmany different ways. Table apronsand chair backs are common usesfor curved parts. Once the shapeand size of the curve is determined,you build a form for gluing, anddecide what thickness of strips touse to make the curved parts.Instead of making a giant compass, I draw thecurve by bendinga thin strip ofwood across thelayout marks.Finish nails holdthe shape whileI mark the curvewith a pencil.After smoothingthe first piece,rough-cut partsare then addedto the form. Aflush-trimmingbit is used in therouter to makeidentical curvesfor the bendingform.Make an Educated GuessI like to use the thickest stripspossible to minimize the numberof parts and glue lines. The morestrips in the lamination however,the stronger it will be, and thelikelihood of the curve springing back away from the form willbe minimized.To get the finished thicknessof 3 4", I could use four strips 3 16"thick, six strips 1 8" thick, eightBentLaminationsMake curved forms without getting steamed.by Robert W. LangComments or questions? Contact Bob at 513-531-2690 ext. 1327or robert.lang@fwpubs.comstrips 3 32" thick or a dozen pieces1 16" thick. It all depends on whatwood is used and how tight theradius of the curve is.I make a good guess at a thickness, and resaw a piece of the material to that size. I then bend thepiece to roughly the curve I want.If it’s difficult to bend, or I hearany popping or cracking noises asI make the bend, I try again witha slightly thinner piece. For thisproject, which uses ash, I startedat 3 16" thickness but ultimatelydecided to use 1 8" for the stripsto make the shelf supports.The next step is to build theform used for bending the curvedparts. The shelf supports finishat 2" wide, but the laminationsare glued together at 21 2". Theextra width means I don’t haveto worry about keeping all of theedges perfectly lined up duringgluing. After the glue has driedovernight, I can get a clean edgeon the jointer, and achieve thefinal width by ripping the part onthe table saw. One more light cuton the jointer will remove any sawpopwood.com

Resawing strips on the band saw is safer and less wasteful than using thetable saw. I cut them a little thicker than necessary, clean up the saw marks,and bring them to final thickness with the planer.MDF sledThin pieces can be sent through the planer on a sled, a piece of 3 4"-thick MDFthat extends past the feed rollers and is clamped to the planer bed.marks. A few quick swipes with acard scraper leave the edges readyfor finishing.To get the 21 4" thickness forthe form, I used three layers of3 4"-thick birch plywood cut tothe inside radius of the curve,and a fourth piece as a base plate.It doesn’t matter what the form ismade from; I used material thatwas left over from another project.I would have used particleboard ormedium-density fiberboard (MDF)if I had found a piece of that first.The radius is 5611 16", whichwould require a long trammel todraw and cut the curve. Instead,I simply marked the end pointsand centerline of the curve, andmarked off the 4" rise at the center.I then drove a 4d finish nail at eachof these points, and bent a thinstrip of wood across them.It takes three hands to bendand mark the curve. If you don’thave someone to help you, drivefinishing nails at an angle closeto the points used to define thecurve. With the midpoint insidethe nail, and the ends outside, thethin piece will hold its shape. Youcan bend the nails to position itexactly where you want it. I cut thecurve on the band saw, being careful to saw just outside the pencilline. Then I used #80-grit sandpaper wrapped on a block of wood toget the curved edge smooth.The First Part is the PatternPolyurethane glue can be messy as it cures. I use a thin bead of glue andspread it out with a putty knife to avoid this.POPULAR WOODWORKING October 2005The first layer of the pattern is theonly one that requires this muchwork. The remaining patternpieces can be marked by tracingthe first one. After cutting themslightly oversize, they are attachedto the first piece with half-a-dozen#8 x 11 4" screws, and the edges aretrimmed with a flush-cutting bitin the router.After attaching the base plate,the surfaces of the form were givena couple coats of paste wax to keepglue from sticking to them.Now make the strips for thelaminations. They can be rippedon the table saw, but it can bedangerous to work with partsthat thin, and nearly half of thematerial will be lost to the sawkerf. By using the band saw, theoperation is much safer and lessmaterial is wasted. I cut the stripsto 3 16" and took them down to thefinished thickness of 1 8" by sending them through the thicknessplaner. I clamped a piece of scrapMDF to the planer bed to carrythe thin pieces. Because the ash Iused was straight grained, I didn’tworry about the edge grain matching, and cut all the strips I neededfrom 4/4 stock.In addition to cutting the stripswider than they need to be, I alsocut the strips about 6" longer.When you glue six pieces togetherat a time, they can slide aroundsome, and each layer is slightlyshorter than the layer next to it.It’s easier to leave them long andtrim them when you’re done.Get Ready to GlueBefore attempting a glue-up, Imade a dry run to make sure myclamping method would work,and that everything I neededwas at hand. To form a fair curve,pressure must be evenly applied.This means a lot of clamps placedclosely together. During the dryrun I determined that 4" or 5"apart was a good spacing.Typically I use yellow glue formost of my woodworking but bentlamination isn’t a standard process. The wood wants to straightenback out, and yellow glue is somewhat flexible after it’s dry. A gluethat dries more rigidly should beused. Epoxy, plastic resin and reactive polyurethane all dry to a rigidline. I chose to use polyurethane(Gorilla Glue) because it doesn’tneed to be mixed before using.I laid the strips out in order,and put a thin bead of glue down

the middle of each strip. I thenused a putty knife to spread outthe bead evenly across eachstrip. I stacked the strips back up,and placed them in the form. Istarted clamping in the center,and worked out to the ends, alternating right and left.Each lamination was left in theclamps for four hours to dry. Afterremoving the bent part from theform, I scraped off the excess glue.After the last part was removedfrom the form, I waited another24 hours to be sure that the gluewas fully cured before moving onto the next step.I cleaned up one edge of eachcurved piece on the jointer. I thencarefully ripped each part to 1 32"over the finished width on thetable saw. This can be done safelyby keeping the part flat againstStarting at the center and working out to each end,clamps are placed every 4" to 5" around the form.After scraping off the excess glue, one edge is evenedup on the jointer. Make sure to keep the curve in contactwith the fence on the outfeed side of the cutterhead. Hanging blocks BENT-LAMINATION WALL SHELFNO. ITEMDIMENSIONS (INCHES) MATERIAL COMMENTSTWL 2 Rearsupports3 421 2* 54* AshFrom 121 8" pieces 2 Frontsupports3 421 2* 54* AshFrom 121 8 " pieces 3 Shelves3 482211 213 4 Ash 4 Hanging 1Ashblocks*Sizes reflect overage for trimmingCut fromlarger blockProfileElevationpopwood.com

the table and tight against thefence at the infeed edge of the sawblade. After this cut, I returnedto the jointer and removed thesaw marks with one pass over themachine’s cutterhead.Form Does Double DutyTo make the 3 4"-wide x 1"-deepnotches in the supports, I put themback in the gluing jig. I added spacers below them to keep the topof each piece flush with the topof the jig. I added guide strips tothe form to guide my router whencutting the notches. To preventmaking two lefts and no rights, Ididn’t trim the ends to their finallengths until all the 3 4" notcheswere cut and the pairs of curveswere glued together.I marked the center 2" of eachpiece and planed a flat in this areawith my block plane. I clampedpairs of curves together, usingscraps of wood to keep the notchesaligned and in the same plane.After the glue had dried overnight, I marked the ends of theuprights from locations markedon the bending form and trimmedthe ends with a handsaw.I used my smoothing plane tofine-tune the fit of the shelves tothe notches. I scraped all of theparts and then hand-sanded themwith #220 grit before assembly.The ends of the shelves slide intothe notches and are simply gluedand clamped.It’s a bit of a challenge to keepeverything lined up during assembly. I started the shelves in thenotches before brushing in glue.To keep the shelves alignedwhile clamping, I placed 3 4"-thicksticks on my bench to support theback edges. This is the distancefrom the wall in the finished shelf.I also made sure that the ends ofGuidestripUse layout lines on the top of the bending form to attach guide strips for therouter. Working from the center, I also established lines for the ends of thesupports. Then I notched the curved parts for the shelves with the router.Notchfor shelfWith the finishedpart back in thejig, I lay out a 2"long flat at thecenter of eachcurved piece andthen plane it byhand. Check thefit by measuring the spacebetween the twoparts at the shelflocations.The ends of theshelves fit in thenotches. Adjustthe fit with a fewswipes with asmoothing plane.Mark the supportlocations on thebottom of theshelves to keepthe parts in lineduring assembly.The other edge is ripped on the table saw, maintaining contact with the tableon the infeed side of the saw blade.POPULAR WOODWORKING October 2005

the back uprights were flat on thesurface of the bench.After a final hand sanding with#280 grit, I finished the shelveswith three coats of lacquer sprayedfrom an aerosol can.Curved parts aren’t hard tomake, and can be both structuraland visually interesting. The ability to make them adds to the skillsthat make a well-rounded woodworker. PWHANGING THE SHELVESTo hang the shelves, I made two small blocks to fit behind the top ofthe back uprights.The dimensions of the blocks aren’t critical, butthey need to fit neatly together, and be tight against the inside of thecurved support. I started with blocks larger than I needed so thatI could cut them to shape while keeping my fingers a safe distancefrom the band saw blade. After cutting the blocks to shape I fit thecurved edge to the back of the shelf support.These can be fastened to a wall with Zip-it anchors (availablefrom your local home center) after drawing a level line on the wall.The matching half of the hanger is glued to the back of each of thecurved uprights. To hang the shelf on the wall, it is simply dropped inplace on the hangers.– RLLay out thehanging blockson a pieceof wood bigenough to letyou cut themsafely on theband saw.Cut the curvefirst, then maketwo short cutsto form theinterlockingjoint. The lastcut frees thehanger fromthe block.Line up the shelves in the notches, then brush glue on all surfaces of the joint.Sticks tosupport shelvesAssemble the shelves on a flat surface, making sure the ends are flat on thetable. Square sticks keep the backs of the shelves in position.The bottom half of the hangingcleat is attached to the wall forming a hook.The other half of the hanger isglued to the back of the shelfsupport, letting the shelves hangnearly invisibly.popwood.com

INGENIOUS JIGSBending Wood the Wright WayCold bending is a whole lot easier with this flexible clamping fixture.In my mind, there are three classifications of woodworking techniques. Thereare many that I classify as “useful,” a smaller number that I think of as “indispensable,” and then a very few that represent atrue breakthrough in woodworking technology. Bending wood is one of the latter.The ability to alter the grain directionas our imagination dictates while preserving the strength inherent in a straight pieceof wood allows us to create the elegantbeauty of a continuous-arm Windsor chairand the inspiring sweep of a vaulted ceiling. We first explored our world in sailingships with bent wood hulls, then left it inairplanes with bent wood wings. Our worldwould be much less beautiful and muchless exciting without this simple woodworking technique.I’m currently engaged in a woodworking project designed to create a little excitement, and bending wood is at the veryheart of it. I’m part of a group of historians and aviators who are recreating the sixexperimental airplanes of the Wrightbrothers, beginning with their model glider of 1899 and ending with the 1905Wright Flyer 3, the first practical airplane.The frames of these primitive aircraft area collection of bent wood parts — ribs,wing ends, braces and skids — ingeniously arranged to catch the wind and lift aman into the air.Photos by Chris SchwarzTrue Geniuses PreferCold BendingWhen most of us hear the words “bendingwood,” we think of steam bending. Thewood is heated briefly in low-pressuresteam to soften the lignin (a glue-like protein that holds the cellulose fibers together). While the wood is still hot, it’s clampedinto a bending form. The cellulose fiberstelescope to conform to the curve, and thelignin cools to hold them in place. Or almost. In actual practice, the fibers neverquite conform, and when you remove thewood from the bending form, there is agreat deal of springback — the wood losessome of its curve. If the wood is not attached to the other parts in the project soas to hold the curve, it may continue torelax and it will spring back even more.This problem plagued the Wright brothers while they were doing their glider experiments — they calculated precise curvesfor the ribs to fly as efficiently as possible,only to have the ribs relax and lose a gooddeal of curvature before they could get theirgliders in the air.To solve this problem, they eventually abandoned steam bending for an earlyform of cold bending. They arranged theparts of the ribs for their Flyers in a bending form, then nailed them together withbrads. They could not use glue — the adhesives 100 years ago were not weatherproof. A good rain and the wings wouldhave come apart.Fortunately, we have a much larger andmore reliable selection of adhesives tochoose from than the Wrights. We decided to make the bent wood ribs of our replica Wright gliders by laminating the partswith a water-resistant aliphatic resin (yellow) glue. You could also use Resorcinol,epoxy or polyurethane glue for an application like ours. If your project won’t beexposed to the weather, you can use almost any good wood glue.To cold-bend wood, first resaw yourwww.popwood.com

INGENIOUS JIGSstock into thin strips and plane it so thethickness is even. The thickness of thestrips depends to a large extent on the radius of the curve. The tighter the radius,the thinner the strips. I use this chart as ajumping-off point: 2" to 4" radius — 3 32" thick 4" to 8" radius — 1 8" thickHelp Kids Build a Wright FlyerThe most exciting woodworking project in 100 years.The year 2003 will mark the 100thanniversary of the first controlled,sustained flight. On Dec. 17, 1903,Wilbur and Orville Wright flew theirfirst powered aircraft, called simplythe Flyer, 852 feet across the sands ofKitty Hawk, North Carolina.Thiscoming anniversary presents a uniqueopportunity to get young people allacross America excited about avia-A replica of the Wright Brothers’ 1900 Gliderthat Nick Engler built and got airborne at KittyHawk, N.C., in late October.tion — and woodworking!The Wright brothers built thegliders and airplanes in their workshop in Dayton, Ohio.These machineswere largely made of wood: spruce forthe straight parts, ash for the bentparts and a little boxwood for thepulleys.The end result of these laborswas that the Wrights, by virtue oftheir ingenuity and craftsmanship,achieved the age-old dream of flight.The story of their woodworkingprojects has become one of the mostinspiring stories in American history.That said, it is becoming harderand harder for young people to acquire the woodworking skills thatgave us the airplane and a thousandother useful and beautiful innovations. High school shop programs arebecoming a thing of the past.Vocational schools train students forindustry, which relies more and moreon computer-aided manufacturing.The old manual machine setups —what we use every time we make acut or drill a hole — are no longerbeing taught on a wide scale, and ourcraft will suffer if we don’t find otherways to introduce young people tothe joys of woodworking.Popular Woodworking has lent itssupport to a unique program of theWright Brothers AeroplanePOPULAR WOODWORKING February 2001Company (WBAC) of Dayton, Ohio,that addresses these concerns directly.The WBAC is a non-profit educational organization of craftsmen,historians and aviators who are building replicas of Wright aircraft, including the 1903 Wright Flyer.They willbuild the Flyer with the involvementof young people across America!Here’s how it works:The WBAChas scripted a learning experience for kids ages 10 to 18 during which they learn a littleaviation, a little history and alittle woodworking. During thisexperience, which takes just afew hours of a morning or anafternoon, the kids build 1 4-scaleribs of the Flyer that they cantake home.Then the whole classcomes together to build a fullscale rib.The kids sign it andsend it to the WBAC in Dayton,Ohio.There, more kids under thesupervision of accomplishedcraftsmen, will assemble the ribs in areplica Flyer, that’s 40 feet fromwingtip to wingtip.And that’s not all. Each of the kidswho works on a rib gets to sign it.TheWBAC also invites each young person to make a prediction about whatthe next 100 years of aviation willbring.All the signatures will be preserved on the replica Flyer, and thepredictions will be edited and assembled into a large book.The completedkid-built Flyer and the book will beunveiled at the Dayton InternationalAirport on December 17, 2002 (ayear before the centennial anniversary), where it will serve as a milepostin both aviation and craftsmanship,pointing 100 years back and looking100 years forward.We’re looking for woodworkers toserve as teachers and mentors tohelp conduct these learning experiences and to communicate the thrillof building something wonderful tochildren.The WBAC will send youinformation on these experiences ifyou’ll just raise your hand and say “I’lldo it.” You can contact them throughthe Internet a www.wrightbrothers.org, or write WrightBrothers Aeroplane Company, KidsBuild a Flyer!, P.O. Box 204,WestMilton, OH 45383.Meanwhile, we’ll continue to report on this exciting woodworkingproject as it progresses. PW 8" to 12" radius — 3 16" thick 12" radius or larger — 1 4" thickThere are other factors to consider: thespecies of wood, the slope of the grain (asit runs between the faces of the strips), thestrength you want, and the amount ofspringback you can tolerate. For maximumstrength and minimum springback, we decided to glue up the ribs from 1 8"-thickstrips, although the radius of the curve wasnowhere near 8".Stack the strips as you will glue themtogether. If you use strips that were all resawn from the same board, flip every otherstrip end for end to reverse the grain slope.Spread a thin layer of glue on the face ofone strip, lay the next strip on top of it,spread more glue and repeat. If you’re laminating a large number of strips, you maywant to choose an adhesive with an extended working time.Before the glue sets, clamp the laminated strip in the bending form. Let theglue set up for its full clamp time. If you’renot sure of the clamp time, wait a full daybefore you remove the assembly from thebending form. As you release the clamps,there will be a small amount of springback.If the curve is critical (as it was for our glider ribs) make the curves in the bendingform slightly tighter to compensate.Making a Cold Bending FormPretty simple, huh? The only real trick tocold bending is in making a form that willapply an even clamping pressure all alongthe laminated assembly. Traditional bending forms consist of two parts, the form(the positive shape) and the press (the negative shape). Both of these parts are normally cut from the same stock. Begin bydrawing the curve you want on the face ofthe stock. Cut the curve with a band saw,separating the stock into two parts. On thenegative part, mark the thickness of thebent wood part. (Tip: Use a compass likea calipers, set it to the desired thickness.Follow the curve with the point of thecompass, marking the thickness with thescribe.) Cut away the thickness on theband saw — this will create the press.The trouble with this traditional bending form is that the press doesn’t compensate for small variations in the thicknessof the laminated stock or a band saw blade

Spread the glue on the surface of each stripwith a 3 8"-32 threaded rod to draw the adhesive out as evenly as possible. Note that I’veplaced the strip on a long scrap to elevate itabove the bench.This allows the extra glue todrip over the edge.Clamp the laminated strips in the bending form,spacing the clamps every 3" — dead center inthe middle of each segment of the press. Idrilled 11 4"-diameter holes in the form to holdthe top face of the clamps and automaticallyspace them.that wanders a hair off the line. Consequently when you apply the clamps, theclamping pressure may not be completelyeven all along the form. This may result inweak laminations or even gaps betweenthe laminations when the glue dries.To ensure that this didn’t happen to ourglider ribs, I designed a compensating press.After cutting away the thickness of thebent wood part, use the compass to markyet another curve on the negative part, thisone 1" larger in radius than the curve youjust cut. Saw this curve then cut the 1"thick piece into 3"-long segments. Adherethe segments back to the negative part temporarily with double-face carpet tape. Gluea strip of canvas to the inside curve of thesegments and cover the canvas with 6-milplastic.When you separate the segments fromthe negative part and discard the tape, theyshould be held together by the canvas likethe tambours of a rolltop desk. This is yourpress. When you squeeze the laminatedstock to the form, arrange the clamps inthe middle of each segment; this will compensate for any variation in stock thickness or inaccuracies in the bending formand keep the clamping pressure relativelyeven.Note: The plastic on the press will keepany glue that squeezes out from betweenthe laminations from sticking to the canvas. To prevent the squeeze-out from sticking to the form, apply paste wax to the formbefore each glue-up.Spreading the GlueJust as uneven clamping pressure will reduce the strength of the lamination, so willan uneven application of glue. You mustspread it as evenly as possible, and I’ve gotjust the ticket. This little trick was shownto me by the good folks at Franklin International (makers of Titebond glue). Getrid of your glue brushes and spread the glueBefore you tighten the clamps, just snug them upto hold the stock against the form.With a scrapof wood and a hammer, tap the top edges of thestrips to even them up.Then tighten the clampsuntil the gaps disappear between the laminations.with the teeth of a 3 8" x 32 threaded rod.The threads spread the glue to just the rightthickness (about 0.005") for a strong jointwith a minimum of squeeze-out. For thisparticular project, I mounted a short lengthof threaded rod in a wooden handle. Between glue-ups, I keep the rod submersedin water to prevent the glue from dryingon the threads. PWNick Engler is a craftsman, pilot and the author of52 books on woodworking. He’s also the director ofthe Wright Brothers Aeroplane Co. — you can findout more about the Wright aircraft he’s helping tobuild at www.wright-brothers.org.4"3/8"-32threaded rodheld in place by nuts3/4"Scrap woodhandleThe perfectglue spreaderIndividual caul segments cut tothe form radius plusthe thickness ofthe laminatedstripsCanvas gluedto the radius ofthe caul.Cover with 6 milplastic afterit dries1 1/4" holes for clamps1/8"stock milled flat and bent in jigwww.popwood.com

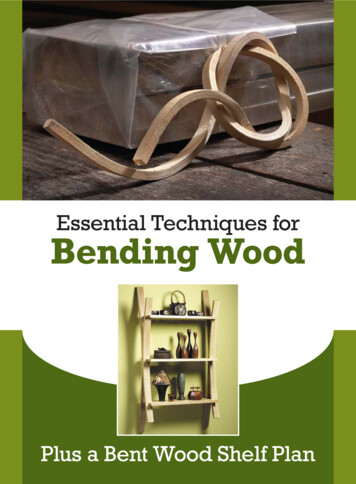

Bend the Laws of LignumB Y C H R I S TO P H E R S C H WA R ZA recent innovation letsyou bend wood withoutsteam or adhesives.The package of wood lookedeverything like a mummy whenit arrived in our shop. The woodwas wrapped in clear plastic, boundby plastic straps and wrapped by moreplastic and cardboard.We peeled away each layer to reveala stick of unassuming 8/4 ash that wasabout 6" wide and 54" long. Aside fromthe fact that the wood was cool to thetouch, it looked like regular ash.I took it to the jointer and planer andmachined it flat. I ripped off a 1"-wideslice and machined that to 13 8" thick,just like any other piece of wood.But then I put that stick into a bending form, and the wood gave up its secretidentity. Working alone, I bent the pieceof ash along its 13 8" dimension andpulled it around a C-shaped bendingform with a 9" radius. In 10 minutes,the wood was bent and clamped up. Nosteam or heat. No adhesives.This is Compwood, a 1988 European invention that allows you to bendroom-temperature wood around a formin multiple dimensions. The lumbercomes to your shop wrapped in plasticbecause it is fairly wet – my piece of ashmeasured 20 percent moisture content.“The New Age? It’s just the oldage stuck in a microwave ovenfor 15 seconds.”— James Randi (1928-)magician, skeptic POPULAR WOODWORKING MAGAZINE April 201136-37 1104 PWM CompWood.indd 36I can bend that. With Compwood, you can bend wood in ways that are surprising. When thewood dries, it holds its shape and can be worked with standard woodworking tools.While it’s wet, you can bend the woodin almost any direction. When it’s dry,it holds its shape and can be worked justlike any other piece of wood.Why Try It?I became interested in Compwoodwhen I saw it in use at Jeffrey Miller’swoodworking shop in Chicago. He’sbeen experimenting with the materialto use in some of his chair designs andhe showed me how it works. Intrigued, Ipurchased some for my own chairs, and Ifirst cut into this batch to make some armbows for some Welsh stick chairs.The Compwood appealed to me forseveral reasons. While expensive, theCompwood allows me to make my armbows without investing in a steam box,which I don’t have room for. Also, thematerial allows me to bend wood to atight radius without a bending strapand without the risk of compressionruptures on the inside curves or delaminations on the outside curves.How tight? There’s a formula for eachspecies. For ash, the smallest bendingradius without a strap is six times thethickness of the work being bent. So my13 8" arm bow could be bent to an 81 4"radius or larger. So a 9" radius could bebent without a strap.The Compwood is also less laborand machine-intensive than a typicalcold-lamination job. When I make coldlaminations, I typically have to sandall the pieces down to 1 8" thick or lessfor tight bends – that’s a lot of machinework. And I prefer to use plastic resinFlexible terms. Compwood can be bentwithout steam or – in many cases – a bendingstrap. It also can be bent in three dimensions.LEAD PHOTO BY AL PARRISH; STEP PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR1/26/11 3:56:21 PM

glue for these parts, and it is nasty andmessy stuff.While I probably wouldn’t considerthe Compwood if I made hundreds ofchairs for a living (I’d probably investin a steam box), it did make sense forme for a short run of chairs.How to Dry itSo how did the material fare? I foundthat it worked as advertised. Afterclamping up my arm bows, I let thewood air-dry in the form for a day, andits moisture content dropped to about12 percent. Then I placed the form in abox that was heated with a lightbulb to85 F and the work quickly dropped to 7percent, according to our pinless moisture meter. That’s when I first removedit from the form.The piece sprang out a little at theends (though it was nothing unacceptable). The reason for the springbackwas that the wood likely wasn’t completely dry.My makeshift “kiln” wasn’t ideal.Miller makes his kilns out of 2"-thickpink foam insulation boards then heatsthe kiln with a ceramic heater with afan. His kilns are leaky, which is goodbecause it allows the moisture to escape.He leaves parts in his kiln for about aweek. The results were impressive.“It was pretty much flawless from aspringback perspective,” Miller says.“It didn’t move a bit.”Relax(ed).One of my arm bows sprung out alittle after being released from the form beforethe arm bow was completely dry. Back ontothe form for you.Chris Mroz, who makes and sellsCompwood to woodworkers and industry through his company, Fluted Beams,says that I probably removed the woodfrom the form too soon. For a piecelike mine, he would dry it at 11

piece of wood to a form. Then you need to wait several days for the part to dry. With bent lamination you need only a form and a way to clamp the thin strips of wood to it. You don’t need to wait an hour or more for the wood to get ready to bend and you don’t need to race like a madman to get a hot